Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2017 | Volume 62, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2017 | Volume 62, Issue 1

Under the Articles of Confederation, these United States were barely united. Unable to agree on either foreign or domestic policy, they sank into economic depression. In May 1787, delegates from 12 states (Rhode Island sent none) arrived in Philadelphia to define a new federal government. In September, they had a new constitution.

But for the Constitution to become law of the land, conventions in nine states had to ratify it. By June 1788, eight states had done so. Anti-Federalists, as opponents of the new Constitution came to be called, saw the Virginia ratifying convention of June 1788 as their last stand.

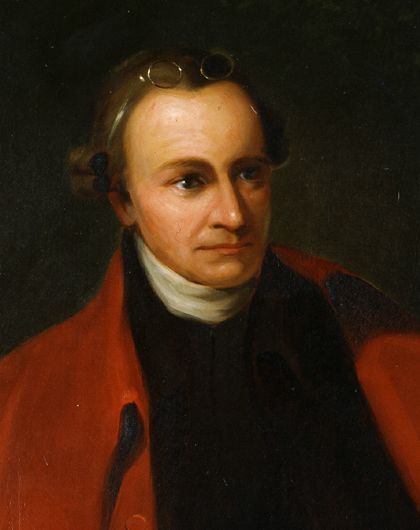

The leading Anti-Federalist in Virginia was Patrick Henry, who was generally acknowledged as the Revolution's greatest orator. The leading Federalist in Virginia, indeed in all the United States, was James Madison, generally acknowledged as the founder most responsible for the Constitution.

"Even more than the Lincoln-Douglas debate over slavery, or the Darrow-Bryan debate over evolution," writes historian Joseph Ellis, "the Henry-Madison debate in June of 1788 can lay plausible claim to being the most consequential debate in American history."

WILLIAM WIRT, IN HIS 1817 BIOGRAPHY OF PATRICK HENRY, described how the twenty-nine-year-old delegate addressed the Virginia House of Burgesses in May 1765 to protest the Stamp Act. Wirt described how Henry, "in a voice of thunder, and with the look of a god," declared that "Caesar had his Brutus—Charles the First, his Cromwell—and George the Third...may profit by their example." Interrupted by cries of "Treason," Henry responded, "If this be treason, make the most of it."

Among those who witnessed Henry's speech in Williamsburg was Thomas Jefferson, then a twenty-two-year-old law student and later Madison's close friend and political ally. Jefferson admired the power of Henry's oratory, but he despised the man. "His imagination was copious, poetical, sublime," Jefferson wrote, "but vague also. He said the strongest things in the finest language, but without logic, without arrangement, desultorily." More bluntly, Jefferson described Henry as "all tongue without either head or heart."

In 1777 Henry clashed with Jefferson—and Madison—over the relationship between church and state. Henry wanted people to pay taxes to support a church of their choice. Compared to having an official state church, as the Virginia colony once had, this was certainly a step toward freedom of religion. Jefferson and Madison wanted a more complete separation of church and state; they argued that churches did not need and should not receive any taxpayer money. Jefferson drafted a "bill for establishing religious freedom" in 1777. In 1785, by which time Jefferson was in France serving as America's ambassador, Madison managed to push aside Henry's proposal for