Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Special Issue - George Washington Prize 2017 | Volume 62, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Special Issue - George Washington Prize 2017 | Volume 62, Issue 4

When you walk through the heavy glass doors of the Americas wing in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, you come face to face with the men and women who made the American Revolution. Paul Revere greets you, head on, just inside the entrance. His iconic likeness—unwigged, shirtsleeved, silver teapot in hand—hangs low enough that his big brown cow eyes meet yours with neither modesty nor condescension. Revere’s is the honest, direct gaze of an honest, direct man: an American gaze. Vitrines holding examples of the silversmith’s craft surround the portrait of the self-made maker. His famous Liberty Bowl stands on a platform just in front of it, like a chalice proffered by a preacher. In the 1950s, the churchiness of the presentation was franker; the portrait and the bowl were placed upon a pedestal with a couple of steps before it, suitable for genuflecting, flanked by American and Massachusetts flags. But even today, in a new and less earnest century, Paul Revere forms the center panel of an American altarpiece.

Behind Revere, on the left, hang a quartet of his fellow revolutionaries. John Hancock, the stalwart merchant, sits at his desk, reckoning, the quill that will ink his bold signature on the Declaration of Independence poised in his right hand. Samuel Adams—the maltster’s son turned politician—stands in a homespun crimson suit, drawn up to his full, modest height, eyes alight with patriotic zeal. Dr. Joseph Warren, the physician, pores over a set of anatomical drawings that seem to prefigure his death and resurrection as the martyr of Bunker Hill. Mercy Otis Warren, the sister of one liberty man and the wife of another, appears lost in thought as she stands before a burbling fountain, displaying the contemplative bent of the intellectual who will write the Revolution’s first major history. the portraits were painted separately, in the 1760s and early 1770s, tumultuous years in the world beyond their gilded frames. they were meant for separate fates, in firelit parlors in middling homes, in a bustling entrepôt at the edge of an empire.

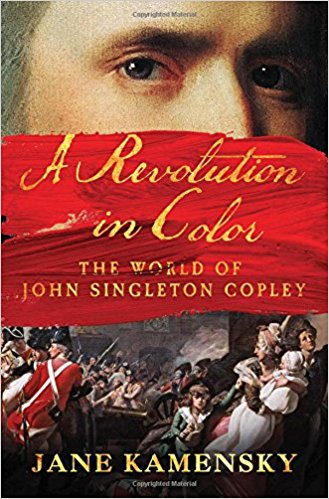

Viewed together centuries later, in the chilly splendor of a great museum, through the glaring light of hindsight, they become a patriotic pantheon: American originals, painted by another of their breed. the labels identify the artist as the MFA owns the largest collection of Copley’s work in the world: scores of paintings spread across four galleries and myriad works on paper tucked away in the department of prints and drawings, where they can be viewed by appointment, under low