Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November/December 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November/December 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 5

Editor’s Note: This is the ninth essay in American Heritage by Joseph J. Ellis, author of a dozen critically acclaimed books on the early years of the Republic including Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in History. Portions of this essay appeared in his recent book, The Cause: The American Revolution and its Discontents, 1773-1783.

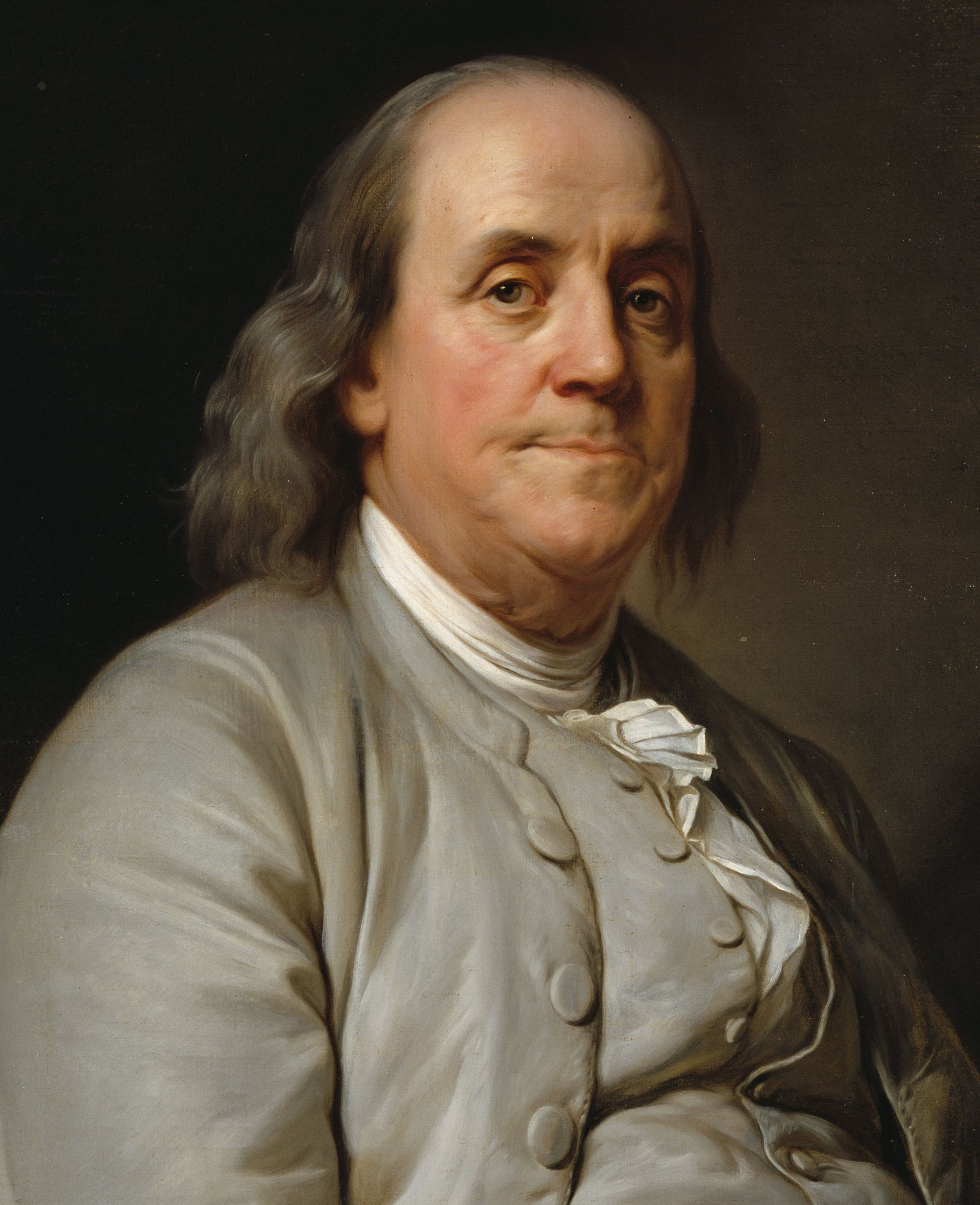

There was surely a mischievous twinkle in his eye when Benjamin Franklin made his outrageous prediction. It came at the end of his Observations on the Increase of Mankind (1751), which provided demographic evidence showing that the population of the British colonies in North America was doubling every twenty to twenty-five years, a rate over twice as fast as the population of England.

This led Franklin to imagine a future Anglo-American empire, about a century later, in which the capital had moved from London to somewhere on the Susquehanna River in western Pennsylvania. Intriguingly, although Franklin’s reading of the long-term demographic and economic trends allowed him to foresee the looming power of a large continent over a small island, he could not imagine a wholly independent American nation. He presumed that America’s expanding significance would occur within the protective shield of the British Empire.

Franklin was describing the eventual emergence of what came to be called the British Commonwealth, with the United States cast in the role subsequently played by Canada and Australia. Given his vantage point in 1751, and his presumption that long-term change would occur gradually in response to America’s sheer geographic and demographic size, that is how American history could have happened. But American independence occurred on a revolutionary rather than evolutionary schedule, in the crucible of a highly compressed political crisis that generated ideas and institutions which continue to define what has become the world’s oldest and most enduring nation-sized republic.

The imperial crisis that culminated in American independence had its origins in the Treaty of Paris (1763) after the enormous British triumph in the Seven Years’ War with France (in America called the French and Indian War). ln addition to several French possessions in Africa and the Caribbean, the great prize Britain acquired was the former French empire in North America. This included all the land from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River, between Canada and the Floridas. The Treaty of Paris effectively laid the global foundation for the first British Empire, with its base in North America.

There was a palpable and broadly shared sense that Great Britain was entering a new chapter in its history that was simultaneously glorious and ominous. The most experienced and informed British student of American colonial policy at the time, Thomas Pownall, sensed a dramatic shift in the atmosphere, “a general idea of some