Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August 1969 | Volume 20, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August 1969 | Volume 20, Issue 5

We stood beside the billiard table in a richly beautiful room in Alnwick Castle, hesitating for a moment before opening the great portfolio which the Duke of Northumberland had laid out for us. On the walls shone the mellow beauty of Titians and Tintorettos. Outside the high windows the great park rolled upward to the hills of the border country. The Duke spoke encouragingly. “My ancestor was one of the commanders of the British troops in Boston in 1775,” he said. “He liked maps. His collection has been here in a black box ever since he came home, until I put it into this portfolio. Do you care to look at it?”

We stood beside the billiard table in a richly beautiful room in Alnwick Castle, hesitating for a moment before opening the great portfolio which the Duke of Northumberland had laid out for us. On the walls shone the mellow beauty of Titians and Tintorettos. Outside the high windows the great park rolled upward to the hills of the border country. The Duke spoke encouragingly. “My ancestor was one of the commanders of the British troops in Boston in 1775,” he said. “He liked maps. His collection has been here in a black box ever since he came home, until I put it into this portfolio. Do you care to look at it?”

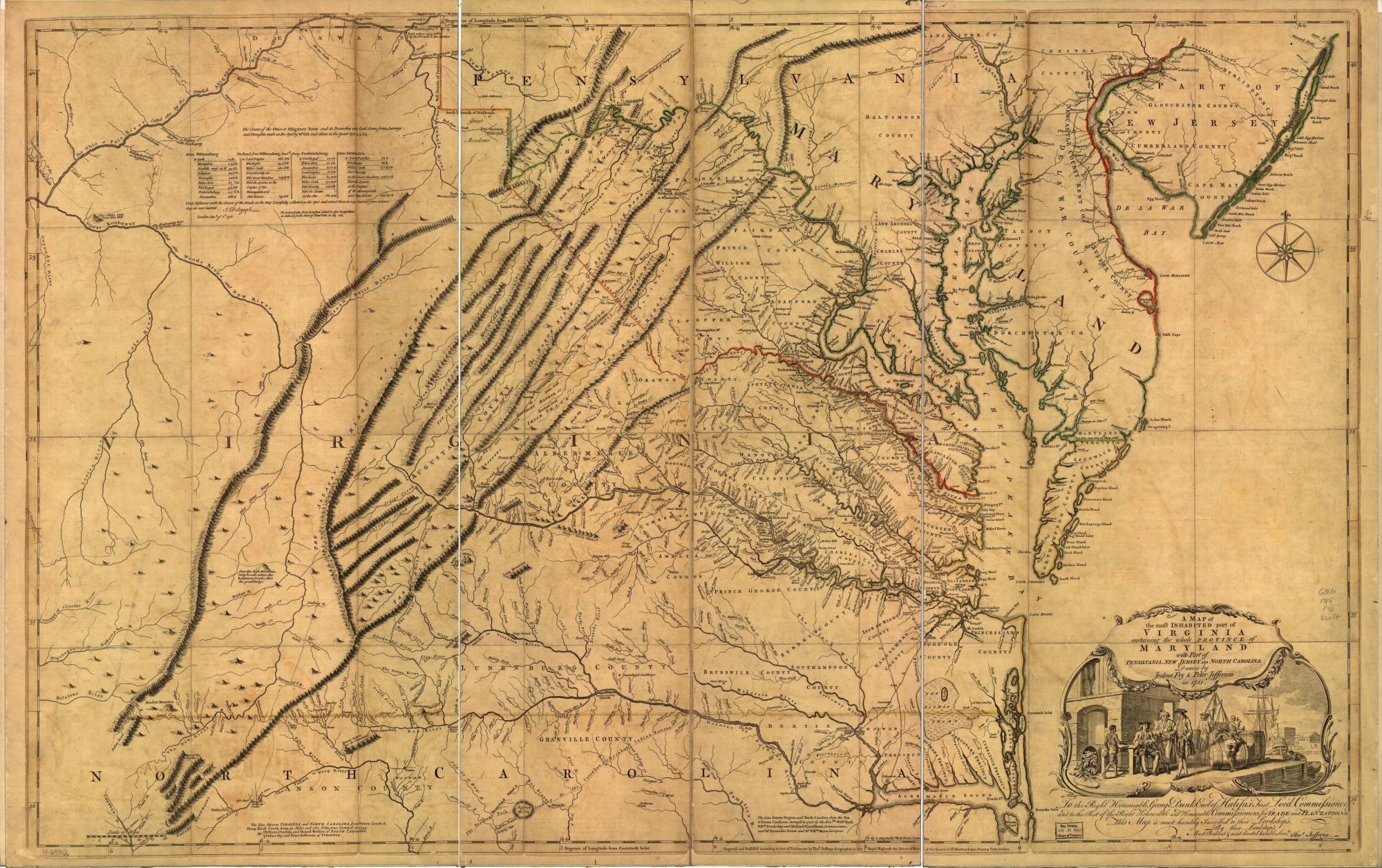

In the billiard room His Grace said, “There, that’s the 1751 map of Virginia.” There it was indeed—the third known copy of the first edition of the famous Fry-Jefferson map. It was quickly apparent that the Duke shared our excitement. After this he took us into his library, a room of noble proportions with the soft amber bookbindings rising to a great height and a small, graceful balcony dividing them halfway up. “Help me lift this portfolio,” said the Duke. “This is the map collection of Hugh, Earl Percy, who was in America from 1774 to 1777. It has never been properly listed; perhaps you could do it for me. Let’s put it on the table.”

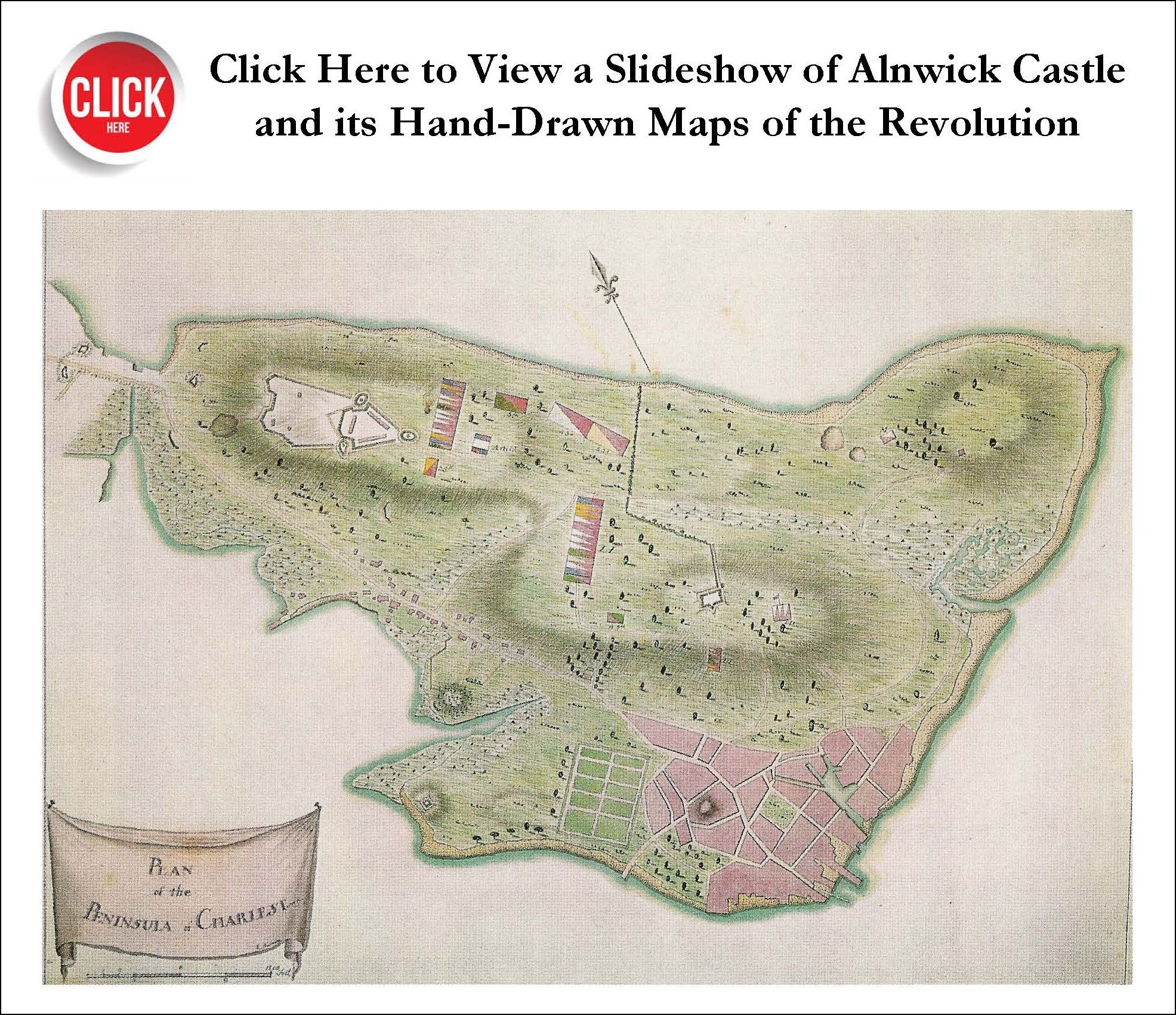

We opened the great folio and began turning over the maps. There were more than fifty, most of them manuscript originals of the terrain of battles and engagements of the American Revolution, many drawn on the day of conflict or shortly after. The signatures of John Montresor, Claude Joseph Sauthier, and Thomas Page, whom we knew to be among the finest surveyors and draftsmen of the Revolutionary era, caught our attention. A sketch of Bunker Hill and Charlestown Neck as seen from Beacon Hill, with British entrenchments and “Rebel Redoubt,” had apparently been made during the bloody storming of Breed’s Hill.

There was a map of New York showed Fort Washington,