Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November/December 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November/December 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 5

Editor's Note: Bruce Watson is a Contributing Editor at American Heritage who publishes a popular and respected history blog called The Attic.

The menu at a dinner table in 1900 might have looked like this:

Juicy beef, flavored with borax and formaldehyde

Green peas, laced with copper sulfate

Pork and beans, with a soupçon of formaldehyde

Lemon ice cream infused with methyl alcohol

Bon appétit, America!

As Americans moved from farms to cities at the turn of the century, upstart corporations such as Nabisco, Heinz, and Campbell’s packaged food for the hungry masses.

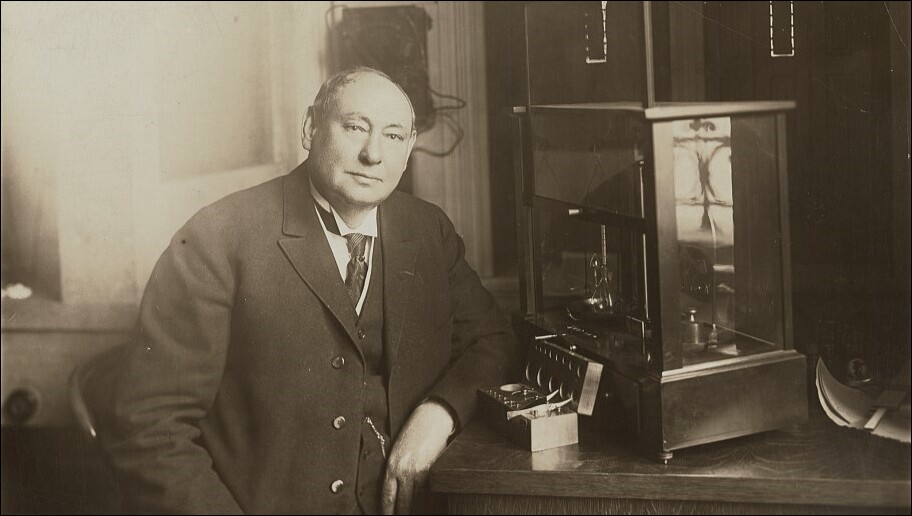

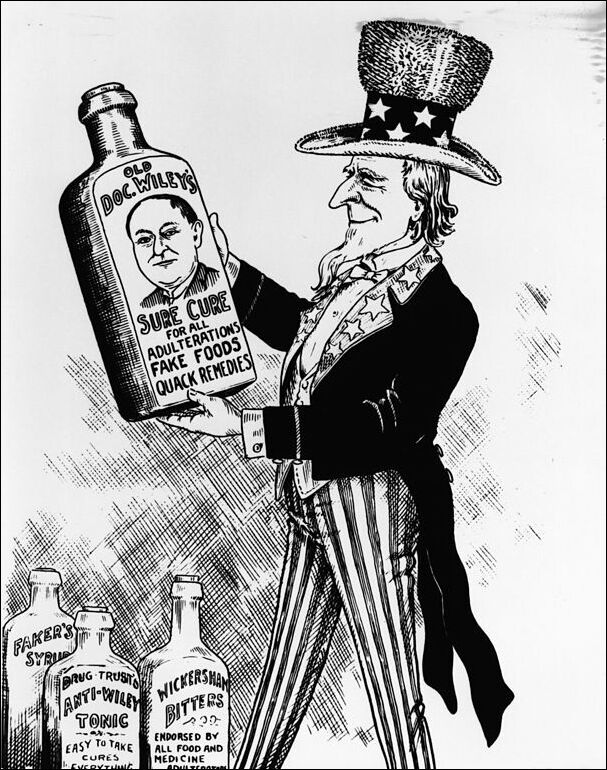

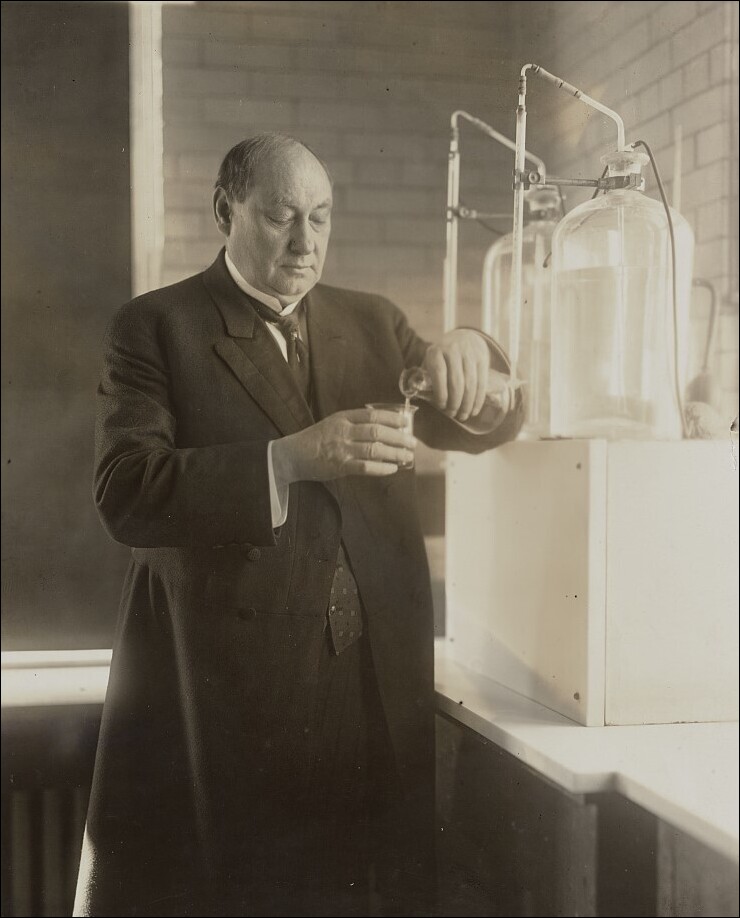

Label after label touted purity, quality, and freshness, but none listed a single ingredient. Then, in 1902, a crusading chemist named Harvey Washington Wiley created “The Poison Squad.”

Born on an Indiana farm, Wiley grew up eating food as fresh as morning. After a stint in the Civil War, he earned a medical degree, then studied chemistry at Harvard. He might have remained a chemistry professor, but his studies in Germany revealed to him a new kind of lab.

Throughout Europe, where hundreds of children had died from bad milk and meat, food additives were being screened, often banned. Professor Wiley learned how to detect additives and to be suspicious. Back in Indiana, he turned his suspicion to locally made sugar, honey, and maple syrup. He was shocked.

So-called sugar was mostly corn syrup. Honey, likewise, with bits of honeycomb added. Maple syrup? Syrupy yes, but not maple.

Wiley’s early studies alarmed the budding food industry, and his character — judged “too young and too jovial” — did not fit academia. In 1882, he left Purdue University for Washington, D.C to become the chief chemist at the Department of Agriculture.

For the rest of the decade, he examined American food. What he found made him sick. Milk was watered down, a pint of water per quart, whitened with chalk or plaster of Paris. Vegetables were greened by copper sulfate. And almost everything contained borax, a buffering agent used in many cleaning products, including the laundry-detergent booster called "20 Mule Team Borax."

Wiley lobbied for pure-food laws, but “the committee rooms of Congress,” he lamented, “are jammed with the attorneys for the industries, a formidable lobby of influential men who will stop at nothing to kill legislation.” Bills were banned, blocked, tabled. Congress slashed Wiley’s budgets. His name was slurred in industry propaganda. He approached the new century all but defeated. Then came war.

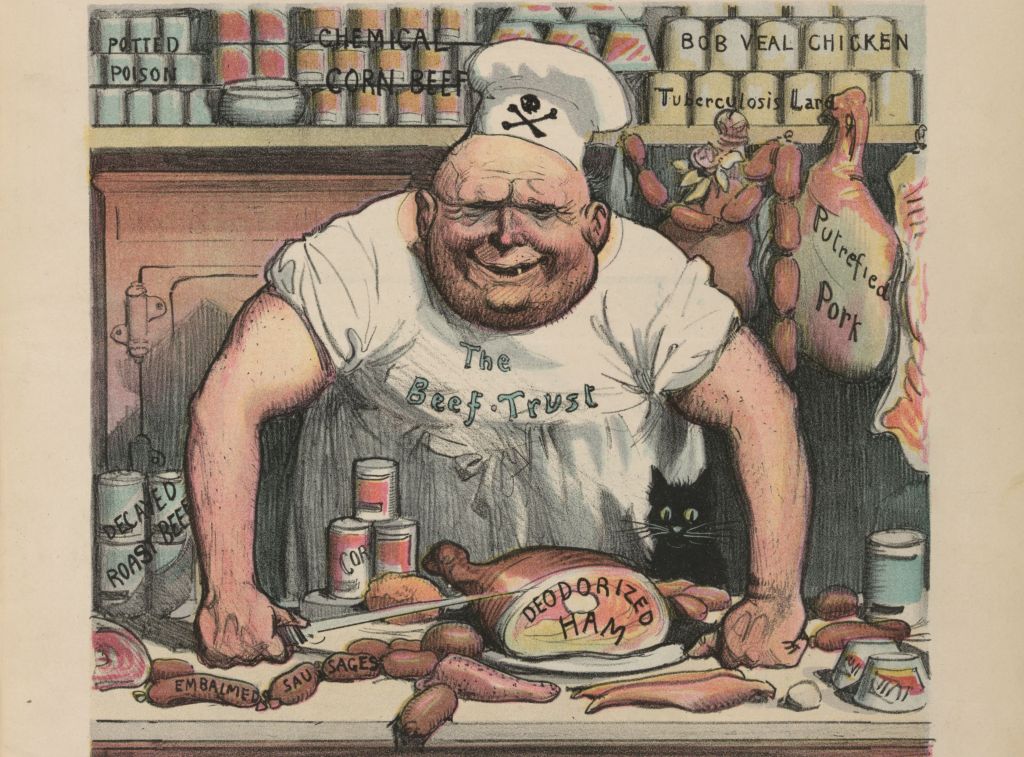

Soldiers in the Spanish-American War ate canned beef by the ton. But cans, packed with ingredients such as borax, chloroform, formaldehyde, and salicylic acid, opened with a “poof!” Officers saw troops sickened by “embalmed beef.” One doctor compared its smell to that of “a dead human body.”

When word reached the public, a pure-food campaign began. Inspired, Wiley introduced another bill in 1902. It was defeated, but Congress gave him $5,000 for “Hygienic Table Studies.”

Under the cover of jargon, he began recruiting human guinea pigs. Promised $5 a month, plus three meals a day, hundreds lined up. Strong stomachs were needed, Wiley warned. Additives would be in each meal, and, despite sickness or death, lawsuits were out of the question.

In the summer of 1902, the trials began. Outside a basement kitchen in the Department of Agriculture building, he hung a sign: “NONE BUT THE BRAVE CAN EAT THE FARE.” And, for the next year, a dozen men of “high moral character” chowed down on food laced with every common additive.

Before and after meals, each strapping man was weighed and measured. Their urine, sweat, hair, and stool were analyzed.

Sworn to silence, the men ate on, but word leaked. A Washington Post reporter coined the name The Poison Squad, and the group was soon eulogized in cartoons, poems, and songs.

The test results were more sobering. Borax caused headaches, stomachaches, and vomiting. Copper sulfate damaged livers and kidneys. The public read of sturdy young men sickened, nauseated, and “losing flesh.”

“One of the reasons that this issue resonated so strongly was that everybody was eating this food,” said Eric Schlosser, author of Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal.

Wiley’s “table studies” spread the alarm. By 1904, America’s first celebrity chef, Fanny Farmer, was campaigning for pure food. The National Consumer League joined the fight. Then, in 1906, the novel The Jungle revealed the nauseating conditions in Chicago meat- packing plants.

“I aimed at the public’s heart,” author Upton Sinclair said, “and by accident, I hit it in the