Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring/Summer 2008 | Volume 58, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring/Summer 2008 | Volume 58, Issue 4

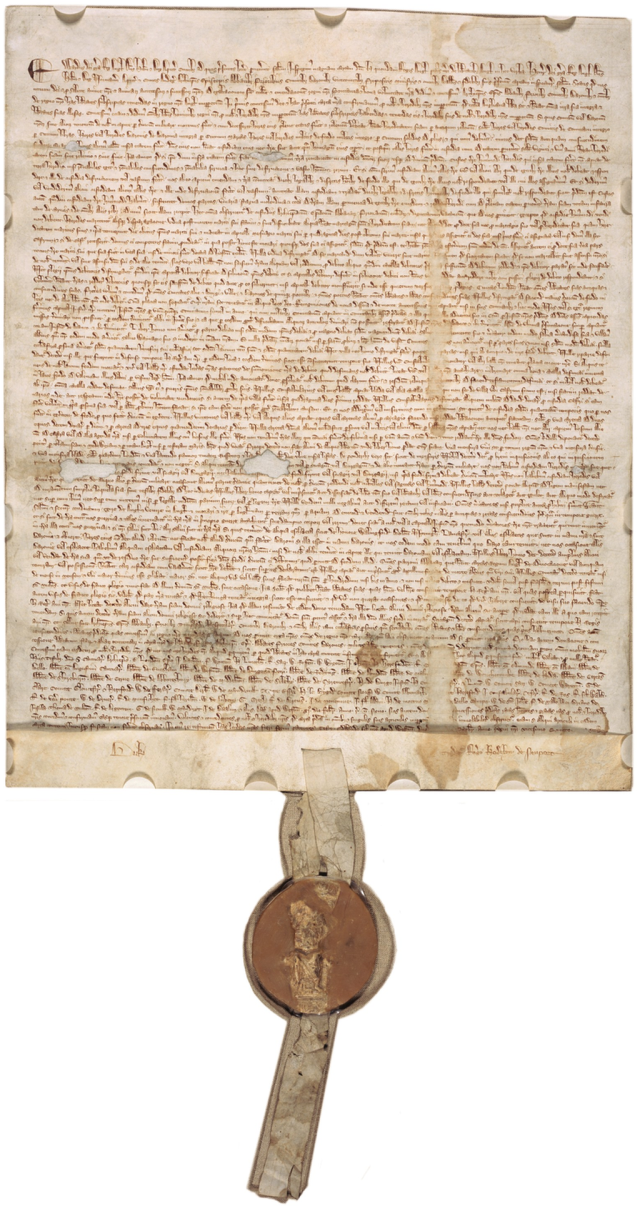

“King John was not a good man,” wrote A. A. Milne in his children’s classic, Now We Are Six. This feckless 13th-century king so badly mismanaged his kingdom that powerful English barons confronted him in June 1215 at Runnymede, a large meadow in the Thames Valley. In tense negotiations, the angry barons outlined their requirements for certain fundamental rights, writing down their demands in a 2500-word document in medieval Latin on a single sheet of parchment.

To avoid civil war, the king affixed his seal to the document, thus binding him and all his heirs to granting his subjects the rights and liberties described therein. Copies were made to be circulated throughout the kingdom.

This charter, which later generations would refer to as the Magna Carta, became a great milestone in constitutional democracy and one of the foundations of British common law.

In March, the National Archives of the United States obtained one of the only existing copies of the Magna Carta (this copy dates from 1297, when the document was reissued), and will display it along with America’s great documents. What could the archivists possibly have in mind when inviting visitors to view this relic of English history before moving on to ponder the great founding documents of the American republic?

The answer is both simple and complex: the story of American constitutionalism—the ideas and process that gave us the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the Emancipation Proclamation, the Reconstruction amendments, and perhaps others—is not complete without understanding what happened at Runnymede so long ago. In this remarkable document lie many of the tenets that would evolve into bulwarks of modern American democracy.

The drafters of the Magna Carta were not graybeards sitting around debating grand philosophical notions about protecting the rights of the common man. Many of the Magna Carta’s provisions dealt entirely with feudal relationships, such as limitations on the extent to which the king could call on the barons to underwrite knighting the king’s eldest son or financing the marriage settlement of the king’s eldest daughter. The barons were seeking to protect their interests against a king who had pushed his claims of power too far. King John had waged an expensive and doomed war in France, quarreled frequently with the pope, and