Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June 1966 | Volume 17, Issue 4

Authors: E. M. Halliday

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June 1966 | Volume 17, Issue 4

In the forest glade where usually, at this hour, only the dark trunks of great pines were to be seen, he was instantly aware of the shadowy figures of perhaps forty Indians, huddled silently before his tent. Among them Davis recognized the chiefs and subchiefs of the most dangerous Apache band on the reservation: the Chiricahuas.

That in itself was not alarming, since Davis often met the chiefs for sunrise discussions. But on this morning things looked different. The chiefs seemed sullen. On top of a nearby knoll, keeping watch toward Fort Apache seventeen miles away—the nearest army garrison—Davis could see a pair of Indians; their silhouettes showed rifles. Another ominous circumstance was that Davis’ Apache scouts—Indians who had been enlisted on the theory that the Chiricahuas could be best policed by their own people—were also gathered in the glade in groups of four or five, and they too were armed. Clearly they expected trouble.

Through Mickey Free, a half-Irish, half-Apache interpreter, Davis learned without surprise that the chiefs wanted to make formal complaints. He ushered them into his tent, and the Indians squatted in a semicircle. Loco, an elderly chief, began a long, slow speech, but a younger man, a subchief named Chihuahua, broke in impatiently. The trouble was easily explained, he said. The Apaches were angry because Davis, as the officer in charge of their camp, had jailed some of them for exercising two time-hopored customs: drinking tiswin (a strong beer made from corn) and beating wives. They had surrendered and come to live peacefully on the i-eservation, Chihuahua said, but they had made no agreement to alter their domestic: habits. What they drank, and how they disciplined their wives, was no business of the U.S. Army.

Davis began an explanation of why General George Crook, his commanding officer, had felt it necessary to prohibit these folkways, but he was shortly interrupted by Nana, the oldest of the Chiricahua leaders.

“Tell the Stout Chief [Davis],” Nana said harshly to the interpreter, “that he can’t advise me how to treat my women. He is only a boy. I killed men before he was born.” And with as much dignity as his bent and wrinkled body could command, Nana stalked out.

Davis knew now that the situation was serious. Nana, despite his eighty-odd years, had only recently surrendered his warriors after a frightening series of bloody raids on Mexican and American ranches, and his status among the Chiricahuas was still far from emeritus. The other chiefs were muttering their approval, and Chihuahua was launching into a more defiant speech, the gist of which was that

Deciding to play for time, Davis told the Indians he would telegraph General Crook, at Prescott, and ask him what to do about the complaints. He knew that the chiefs feared and respected Crook, who had put them on the reservation in the first place. The meeting broke up in a mood of tense and temporary compromise.

Having posted his most trusted Apache scouts as watchmen, Davis rode to Fort Apache and sent his telegram. Necessarily it had to go by way of the army post at San Carlos, sixty miles to the south, and Davis knew it would be at least a day before he heard from Crook—maybe more, since it was already the end of the week. After alerting the officers and men at the fort for possible action, the Lieutenant whiled away some uneasy hours on Saturday in the limited weekend diversions of a far-western garrison. Periodically, scouts came in from Turkey Creek to report a state of restless suspense there: the Chiricahuas were waiting.

By Sunday morning there was still no reply from Crook, but Davis hopefully assumed some sort of military preparations must be under way at the General’s end of the line. (He was to discover later that an officer at San Carlos, acting on the advice of a drunken colleague, had never forwarded the message at all.) Late Sunday afternoon there was a post baseball game at Fort Apache. Davis was umpiring, in what was undoubtedly a distracted state of mind, when Mickey Free and Chato, top sergeant of the Apache scouts, galloped in to report that an undetermined number of the Chiricahuas under Geronimo and Nana had broken from the reservation and were heading for their old haunts across the Mexican border.

Davis immediately told the telegraph operator to wire Crook again. Nothing happened: the line had been cut. While the bugles at Fort Apache blew boots and saddles, Davis hurried back to his camp at Turkey Creek to investigate. He was relieved to find his company of Apache scouts in formation in front of his tent, awaiting orders. He knew, however, that among them were many blood relatives of the renegades who had gone with Geronimo. The next few moments would tell whether or not he had a full-blown mutiny on his hands.

The Lieutenant ordered the scouts to ground arms while he went into his tent for extra ammunition to issue before they took up the pursuit. Dusk was coming on, and he would have to light a lamp in the tent —an easy mark for a

“Shoot the first man who raises his gun from the ground,” Davis ordered. He went into the tent and lit the lamp. At that moment three Apache scouts slipped from the formation and disappeared quickly into the darkening brush—but that was all. Very shortly the rest of the company was on the march, the best trailers in the outfit tracking the fugitives’ hoofmarks slowly but surely under the Arizona stars. But Geronimo and Nana had mounted their people on good horses, and by now were oft to a long head start.

Thus began what was in some ways the most extraordinary Indian campaign in the history of the West. Lieutenant Davis himself, looking back many years later, summed it up as succinctly as anyone ever has, and with a proper degree of wonder: In this campaign thirty-five men and eight half-grown or older boys, encumbered with the care and sustenance of 101 women and children, with no base of supplies and no means of waging war or of obtaining food or transportation other than what they could take from their enemies, maintained themselves for eighteen months in a country two hundred by four hundred miles in extent, against five thousand troops, regulars and irregulars, five hundred Indian auxiliaries of these troops, and an unknown number of civilians.

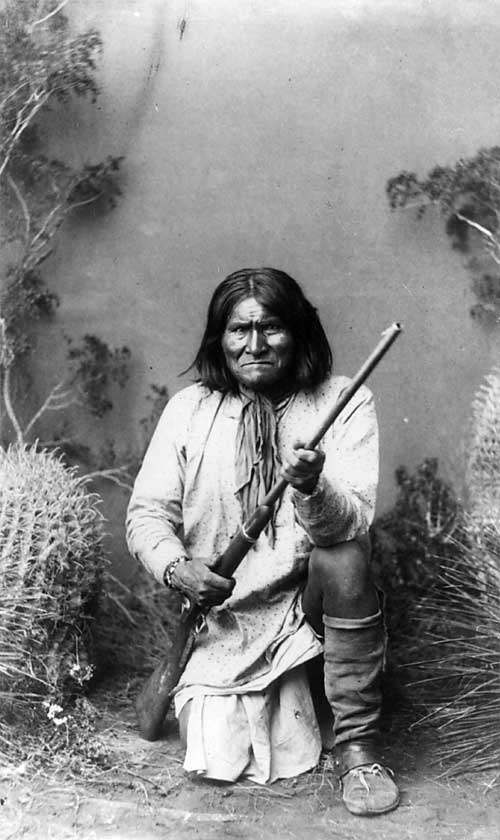

That terse statement goes far to explain the fact that, of all American Indian leaders, Geronimo may well be the most famous. It is nevertheless a curious fact, for he was not a man of great stature—a “patriot chief,” like Tecumseh, Crazy Horse, or Chief Joseph, leading whole tribes in a noble but hopeless stand against the rape of their homeland. Nothing in Geronimo’s record suggests that he was capable of deep thought or feeling; nor was he a chief by reason of family precedent. He became the leader of a small band of Apache raiders much the way a gangster takes over a “mob”: by hard force of personality and skill in conducting field operations.

But when it came to making a mark in history, there was much in Geronimo’s favor. It was his fortune to be the last of a succession of Apache leaders who for well over a hundred years terrorized Mexico and the Southwest with harrowing raids from their mountain hide-outs. His depredations of 1885-86 were committed when Arizona and New Mexico were strenuously working to emerge from the raw frontier and become a reasonably civilized part of America. Miners, ranchers, and farmers clamored for protection; territorial newspapers constantly upbraided the Army for its failure to destroy this last Apache menace, and the territorial governors again and again petitioned Washington to take more drastic steps. By the autumn of 1885 the whole country was aware that large segments of the United States and Mexican armies were unable to catch one fugitive remnant of Apache desperadoes, and the

The fox, moreover, had an intriguing name. It seems doubtful that Geronimo would have become a semilegendary figure if he had been widely known by his Apache name, which was Goyakla—“the Yawner.” No one can imagine World War II paratroopers shouting “Goyakla!” as a war cry when they plunged from airplanes; nor could they have aroused much adrenaline with such a name as Nana. But “Geronimo!” rolls off the tongue with satisfactory resonance and impact; for obscure linguistic reasons it carries intimations of excitement.•

There was, of course, a long and sensational historical background for the popular image of the Apache raider. Unlike other southwestern tribes—the Navahos, for instance, or the Pueblos—the Apaches had made only a truculent adjustment to the arrival of Western civilization. They seemed disdainfully uninterested in settling down to weave blankets, raise sheep, or farm. A relatively primitive tribe with nomadic habits, they lived in small, semi-independent bands, in the simplest kind of improvised shelters—brush “wikiups,” covered with whatever was handy—which would have looked uninhabitable to the Plains Indians with their proud buffalo-hide tepees. In summer the Apaches climbed into the high mountain parks of the Rockies and the Sierra Madres: in winter they came down to the warmer lands along the banks of the rivers. They ate almost anything. Venison, beef, or horseflesh was fine when they could get it easily; otherwise jack rabbits or even field rats were meat to them, supplemented by mescal, fruit of the cactus, sunflower seeds, acorns, berries, and nuts.

Physically, the Apaches had become a specialized type. Implacable natural selection, helped along by infanticide when a child seemed to be feeble, had produced over the course of a few centuries a formidably rugged breed. Not tall—the typical Apache warrior was perhaps five foot seven—they were lean and muscular, broad of shoulder, deep of chest, and with legs that seemed thewed with spring steel. Their women, though they aged fast, were lithe and tough: childbirth, for instance, was but an hour’s interruption to whatever other labor a wife happened to be occupied with at the time. It was no news to hear that a band of these Indians, including women and children, had travelled forty miles a day on foot, across precipitous mountain canyons or the most arid stretches of desert. The Apache’s resistance to heat and his water metabolism almost rivalled that of the camel: he could be “hilarious and jovial” (observed an army officer who knew the tribe well) “when the civilized man is about to die of thirst.”

But the most important fact about the Apaches was simply this: they were marauders by profession. As far back as the oldest of them could remember, plunder had been their regular way of life. Above a bare susbsistence level they depended on their victims for nearly

Yet once a raid was actually in progress, a sinister efficiency took over. Masters of stealth, the Apaches would meticulously survey the scene so as to anticipate just what resistance they might encounter; then they would pounce out of the night upon their quarry, killing all males over ten or twelve, and capturing women and little children for use as slaves or hostages. It is significant that scalping was not a common Apache practice: loot, not trophies, was what they were after, and honor was to be measured as much by material gain as by valor. Their ferocity was, so to speak, of a professional variety.

The history of American-Apache relations, starting with America’s acquisition of much of the Apache homeland after the Mexican War, was a bloody one, relieved only by scattered attempts at peaceful coexistence. Both Confederate and Union troops in the Southwest fought Apaches during the Civil War, and grew grimly accustomed to their maddening guerrilla tactics. The Confederate governor of Arizona, Colonel John R. Baylor, declared to Jefferson Davis that “extermination of the grown Indians and making slaves of the children is the only remedy.” Davis, shocked by the harshness of the prescription, indignantly vetoed it. But General J. H. Carleton, Union commander in the Southwest, instituted a scarcely gentler policy by ordering that all Apache men “are to be slain wherever and whenever they can be found”; the women and children were to be taken prisoner. Meanwhile, in 1863, Mangas Coloradas, the greatest of Apache chiefs, was “captured” by Federal soldiers while discussing a possible peace treaty; then he was provoked into “trying to escape” and was shot to death.

But by the 1870’s, the most sanguine and sanguinary hopes for wiping out Apache manhood were foundering. The ravished towns and haciendas of northern Mexico lay more helpless than ever under the strokes of the marauders, and across the border in Arizona and New Mexico settlers were endlessly haunted by the Apache spectre. An investigator appointed by President U. S. Grant reported in 1871 that the “extermination” policy “has resulted in a war which, in the last ten years, has cost us a thousand lives and over forty millions of dollars, and the country is no quieter nor the Indians any nearer extermination than they were at the time of the Gadsden purchase.” It was decided to combine the stick with the carrot: as many Apaches as possible would be lured onto reservations, while the adamant hostiles would be hunted

It was to effect this approach that General William T. Sherman, the Army chief of staff, sent to Arizona an officer who, when his long career was over, would often be called the greatest Indian fighter the West ever knew. General George Crook, however, was more than a successful subduer of the red man: he was at the same time a sympathetic friend. He was free of the ethnic bias that made most Americans regard Indians as possibly higher animals but decidedly lower humans: “With all his faults,” Crook once declared to a graduating class at West Point, ”… the American Indian is not half as black as he has been painted. He is cruel in war, treacherous at times, and not over cleanly. But so were our forefathers.” Along with such blunt views as these, Crook had a personal demeanor that was disconcerting to some but impressive to all. He disliked official uniform, usually dressing in comfortable hunting clothes; he had a great, forked beard which he sometimes braided for convenience; he was taciturn and often moody—and he attracted to his staff some of the most intelligent and devoted young officers in the frontier army.

As a result of a fine Civil War record plus some outstanding exploits against the Yakimas and Paiutes in the eighteen fifties and sixties, Crook already had a high reputation when he was assigned as commander of the Department of Arizona in July, 1871, at his brevet rank of brigadier general. With characteristic vigor and contempt for the orthodox, he launched a program of negotiation salted with chastisement that in. four years had most of the Apaches on reserves in New Mexico and Arizona. His campaign innovations included heavy reliance on pack mules instead of horses—because of their greater endurance and mountain-climbing ability—and selection and training of a corps of Indian scouts who soon gave new meaning to an old saying of the Southwest: “It takes an Apache to catch an Apache.” The idea of Chiricahua ex-warriors being deliberately armed and equipped by the Army and sent out to pursue their own kin struck many frontier observers with dismay; but Crook had learned that a counterpart to Indian ferocity was Indian loyalty—if his employers proved to be worthy of his trust.

Unfortunately, Crook had more to contend with than Apaches. His surprisingly successful efforts to teach the new reservation Indians the rudiments of farming were sabotaged by white greed for money and land. The business of supplying rations to the government for use by peaceful Indians was already one of the dirtiest in the annals of American enterprise. To cheat an Indian was commonly regarded as a perfectly good way to make a living, and Crook’s young officers fought an endless struggle against watered stock, false weights, and adulterated supplies. Nor could many white settlers tolerate the sight of Indians becoming self-sufficient on good, fertile land: it meant less business for contractors, and less land

Crook’s policies were nevertheless so generally successful that in 1875 the War Department moved him to the northern plains, where he was soon deeply involved, along with such officers as George Armstrong Custer, against the hostile Sioux. By the time Custer and Crazy Horse had gone to their doom and things had quieted down in that region, the Southwest was again afire with Apache terror. Cochise, one of the trrbe’s great patriarchs, had died as a reservation Indian. But other chiefs who still revered the valiant memory of Mangas Coloradas had now taken over the leadership of the Chiricahuas and their cousins the Mimbrenos: Nana, Loco, Victorio, Naiche (son of Cochise), Chato—and Geronimo. Operating sometimes together and sometimes only with small, individual bands, these tireless outlaws rejected the miserable certainties of the reservation for the desperate freedoms of the old Apache way. Weaving back and forth across the Mexican border, they repeatedly ambushed both Mexican and American troops sent in pursuit of them; they slaughtered scores of civilians as well as soldiers, and stole hundreds of horses and whole herds of cattle. The success of their baffling maneuvers drew Indian recruits from the American reservations every time they swooped into New Mexico or Arizona, and the whole situation began to go—from the white point of view—precipitately downhill.

To try to halt the debacle, General Crook was ordered back to Arizona in the late summer of 1882. He began a series of patient interrogations and conferences with Apache leaders to discover their grievances, and he set about the unpleasant task of ridding the reservations of unscrupulous and grafting agents, squatters, and traders. In October he issued general orders to his troops that emphasized an approach to Indian affairs almost eclipsed since his departure from the Southwest in 1875. “One of the fundamental principles of the military character,” he said, “is justice to all—Indians as well as white men. … In all their dealings with the Indians, officers must be careful not only to observe the strictest fidelity, but to make no promises not in their power to carry out.” It was a noble ideal, and the final crisis of Crook’s career would come in a strenuous effort to make it a reality.

Crook’s enlightened attitude, coupled with the growing efficiency of his corps of mule-pack troopers and enlisted Apache scouts, soon began to bear fruit. Slowly but steadily the restlessness of the reservation Apaches subsided, and Crook was left free to operate against the holdouts, most of whom were Chiricahuas.

Chato—who later became Lieutenant Britton Davis’ most devoted scout—unwittingly made a serious mistake in the spring of 1883. Like many of the Apaches still at large, his fighters had managed to equip themselves with Winchester repeating rifles—booty from assaulted pack trains and ranches. The Winchester was a fine weapon, with a more lethal capacity than the ordinary rifles of the Mexican and American armies. But ammunition for it was hard to get. Usually it meant a sally across the border into American territory, where opposition from the far-ranging troopers was sure to be tough and persistent.

Chato took the risk, and in true Apache style engaged in a certain amount of rapine along the way. Near Silver City, New Mexico, on the morning of March 24, 1883, his band of twenty-six encountered Judge H. C. McComas, driving his wife and six-yearold son toward Lordsburg in a frontier wagon. They were a prominent family, but to Chato they were just ordinary white settlers, and fair game. His band descended on the McComas wagon like wolves, shot the judge seven times, clubbed the resisting Mrs. McComas to death, and rode off with Charlie McComas as a captive. A stagecoach reached the scene soon afterward, and by the next day a new wave of public exhortation was demanding an end to the Apache menace in the Southwest.

Chato and his party by this time had acquired their ammunition and slipped back into Mexico, having killed a couple of dozen other settlers in the process—but one of their number, a young man whom the American soldiers called Peaches because of his unusually light complexion, stayed behind. Britton Davis found him visiting some of his relatives near San Carlos, and arrested him without difficulty. More important, Peaches asserted that many of the Apache outlaws were growing tired of war, and he agreed to guide General Crook into the heart of the Sierra Madres—to their secret and almost inaccessible retreat. It was an opportunity not to be missed.

Crook’s carefully planned campaign into Mexico got under way on May 1, 1883. It was in several respects a novel expedition. For one thing, the American and Mexican governments had explicitly agreed that there was to be no difficulty about crossing the border as long as the object was the destruction or capture of the hostile bands. For another, the make-up of Crook’s force was a kind of double-or-nothing bet on the reliability of Indian auxiliaries: 193 of his fighting men were Apache scouts, well armed and selected for their superb physical fitness, while there were only 42 enlisted white soldiers and nine officers. Equipment was cut down to bare necessities. Except for the personal kit that no

According to Crook’s adjutant, Captain John G. Bourke, most of the outfit was in high spirits as they descended into northern Mexico toward the Sierra Madres, despite the rather depressing character of the countryside: On each hand were the ruins of depopulated and abandoned hamlets, destroyed by the Apaches. … The sun glared down pitilessly, wearing out the poor mules … slipping over loose stones or climbing rugged hills … breaking their way through jungles of thorny vegetation. … Through all this the Apache scouts trudged without a complaint, and with many a laugh and jest. Each time camp was reached they showed themselves masters of the situation. They would gather the saponaceous roots of the yucca and Spanish bayonet, to make use of them in cleaning their long, black hair, or cut sections of the bamboo-like cane and make pipes for smoking, or four-holed flutes, which emitted a weird, Chinese sort of music. …

Passing through the little towns of Bávispe and Basaraca, where they were feted with enthusiasm but little else by poverty-stricken Mexicans, they began to hear lurid tales of recent Chiricahua operations. The name of Geronimo was frequently mentioned, and Bourke concluded that the Mexicans regarded him as a kind of devil incarnate, “sent to punish them for their sins.”

By May 9, the expedition was well into the Sierra Madres. The going was extremely rough, up mountain trails so steep and narrow that five supposedly surefooted mules plunged over precipices to their death. Peaches led the command up and down the corrugated ridges and across deeply gashed canyons into country none of the white men had ever seen, and eventually they emerged from a gorge into a small natural amphitheatre some 8,000 feet up—a favorite camp site, the guide said, of Geronimo’s band. This eyrie was empty now; but a few days later Captain Emmett Crawford, pushing on with an advance party of Apache scouts, surprised a Chiricahua encampment, killed several of the hostiles, and captured four children and a young woman.

This proved to be the beginning of the end of the campaign. As the young woman told General Crook, her people were “astounded and dismayed” when they realized that the Americans, with Apaches as guides and allies, had penetrated to the innermost reaches of the Sierra Madres, where they had always felt safe from pursuit. Geronimo and Chato, she said, were away on a raid; but she was sure that when word of this new development reached them, they would find most of their warriors in a mood to surrender.

She was right. She herself was sent out as an emissary with the bad

During the next few days, as more renegades continued to give themselves up, Crook began a close acquaintance with Geronimo that was to continue off and on for seven years, with little admiration on either side. Unlike many of the Apache leaders, in whom an easy candor and ingenuousness offset courage and ferocity, Geronimo struck the General as deceitful, arrogant, and vindictive—”a human tiger,” Crook said later. The Apache headman was a windy talker, and he now gave a long discourse on how badly misunderstood he and his people had been, and how anxious they were to live on the American reservation and work peacefully—if only they could be guaranteed good treatment. Crook, as usual, said little, but made it clear that fair treatment could be reasonably expected if they returned with him, while the alternative, which he was perfectly willing to undertake, was relentless warfare against any Chiricahuas who did not care to come in. After much further talk, mostly from the Apache, it was agreed that Geronimo, Chato, and some of their followers would be allowed a respite of “two moons” in which to gather up the elements of the Chiricahua bands still scattered in the Sierra Madres. They then would make their way to the United States, where General Crook would have preceded them with the Indians already in hand, and all would go onto reservations.

The remarkable thing was that Geronimo kept his part of the agreement, though admittedly several months later than he had promised. Crook brought over 300 Apaches back from Mexico in June, 1883—an amazing achievement—but nearly 200 remained in the Sierra Madres. In October, with territorial newspapers snarling at Crook’s “folly” for not having destroyed them all when he had the chance, Lieutenant Britton Davis was sent to the border to see if he could discover what was going on in Old Mexico. After a wait of about a month, he was rewarded by the arrival of several bands, including those of Naiche and Chato. Geronimo, these Indians assured Davis, was on the way—but it was spring of 1884 before the famous outlaw rode into Davis’ camp, leading approximately eighty Chiricahuas.

It was Davis’ first encounter with the man who a year later was to give him so much trouble at Turkey Creek, and it occurred in a manner that the Lieutenant found highly expressive of Geronimo’s character. As the Indians approached his camp, Davis sent Apache scouts to meet them and explain that the American soldiers

Davis explained that certain members of Arizona’s civilian population, often fortified by whiskey, were ranging the border area looking for Apaches to shoot or hang, and that the Army’s role was to conduct the Indians safely to San Carlos. This might not be easy, especially since Geronimo, a do-it-yourself prodigal, had brought with him a herd of 350 fatted cattle—stolen from Mexican ranches to trade to his tribesmen when he reached the American reservation. It meant slower travelling, and more chance of interference.

Sure enough, when the whole party was camping one night near a ranch house, there appeared on the scene two men in civilian clothes—who identified themselves, however, as a U.S. marshal and a collector of customs. The marshal handed Davis a subpoena and announced that they were there to take Geronimo’s band under arrest to Tucson, to stand trial for smuggling and murder. If Davis failed to help them, they would organize a posse in a nearby town, and the Lieutenant could take the consequences.

Davis was amicable, but underneath he had no intention of giving up his charges before they got to San Carlos. That evening he entertained the marshal and the collector with such generosity that both of them went to bed in the ranch house numb with whiskey. Then Davis told Geronimo that at sunrise the marshal was planning to take all of his cattle away from him, and that a sneak departure toward San Carlos was advisable. Geronimo, at first irascibly unwilling, was moved to action by a gibe from Davis that the feat might be too much for even Chiricahuas to pull off. Ho! said the chief. When the marshal and the collector came sleepily out of the ranch house the next morning, they found only Britton Davis, sitting patiently beside his mule, waiting to explain that Geronimo and the Apache scouts had unexpectedly decided to leave in the middle of the night. He was not quite sure, he said, where they had gone. The marshal told Davis he could go to hell, and the Lieutenant then rode off to catch up with Geronimo and the scouts.

No part of the Geronimo saga has been more romanticized for commercial consumption than the background of the outbreak of 1885, after the Chiricahuas had been on the reservation for over a year. A recent movie, for instance, supplied the Apache leader with a set of motives worthy of Sitting Bull: there were brutal army officers, scenes of public humiliation, and outrageous land grabs. The fact is that in officers like Crook, Bourke, Crawford, and Davis,

But what moved a minority—about one-fourth—to the final break from the reservation was not so much what they were obliged to do in their new environment as what they were forbidden to do. As related at the start of this account, the prohibition against tiswin and wife-beating was particularly galling; and for some, including Geronimo and Nana, total abstinence from brigandage was more than they could bear. Davis felt that Geronimo never ceased to brood over the fact that “his” herd of cattle had been taken from him when he came in from Mexico. It was confiscation of rightful booty, from the Apache standpoint, and it engendered in Geronimo a wrath almost equal to that of Achilles, who, it will be remembered, retired to sulk in his tent for a similar reason at the beginning of the Trojan War.

Geronimo, together with Nana, Naiche, and something above a hundred of their compatriots, rode off from Turkey Creek on May 17, 1885, with Lieutenant Davis and his Apache scouts in pursuit. Their ultimate surrender took place on September 4, 1886. An odd thing about the long campaign which led to that surrender is that despite the tremendous national interest it aroused, most of its details are less than stirring. The truly exciting days of Apache-American warfare were already in the past: the odds were now much too heavy against the Indians, and their survival depended almost entirely on their skill at evasion. In this, however, Geronimo proved himself to be one of the virtuosos of all time. “It is senseless to fight when you cannot hope to win,” the old warrior observed to an interviewer twenty years later, when he had become a celebrated captive. He knew, in 1885-86, that “winning” was out of the question—but he soon demonstrated that a fugitive freedom could be prolonged over an astonishing length of time.

The meager number of the renegades, while it made pitched battle unprofitable, greatly facilitated fast movement and effective concealment. They rode their horses at a killing pace, and

The military obstacles were very hard for anyone not actually in the field to understand. Lieutenant General Philip Sheridan, now the commanding general of the Army, and a West Point contemporary of General Crook’s, felt both his understanding and his patience dwindling as the months went by and as journalistic agitation for the capture of Geronimo steadily ballooned. Even President Cleveland, responding to political pressure, was irritably anxious to see the Apache gadfly disposed of—preferably, he said, by hanging, which would certainly have been most satisfactory to the enraged citizens of Arizona and New Mexico. If that was impossible, nearly everyone in government circles agreed, the thing to do was send all the Chiricahuas to some safe place in the East the minute they could be rounded up.

In January, 1886, things suddenly took a new turn. A detachment under Captain Crawford caught up with Geronimo’s band, and with great good luck captured all of their horses and camp equipment. Eight months of running had tired the renegades, and they decided to negotiate. But on the day the talks were to occur, some Mexican soldiers from nearby Sonora towns suddenly attacked Crawford’s camp, by mistake, and before the confusion was cleared up, Crawford had a fatal bullet in his brain. The parley was postponed until March, at which time Crook himself journeyed into the Mexican mountains near San Bernardino and met in conference with Geronimo, Naiche, and Chihuahua. To Crook’s disgust, Geronimo was more windy-worded than ever, overblown with concern about his reputation and full of blame for everyone but himself for what had happened since May, 1885. Nevertheless, he agreed to surrender on condition that he and his band should not be held prisoner in the East for more than two years, and that their families should be allowed to go with them.

It looked like the end; but after Crook had returned to Arizona, leaving a small party of Americans and a group of Apache scouts to conduct the surrendered

But it was too late to patch up the difference between the two old West Pointers. Another stiff exchange of telegrams ended with Crook asking to be relieved of his command. Sheridan quickly complied.

Now the last chapter in the “Geronimo campaign” was about to unfold. The man who replaced Crook was an old acquaintance, and (though Crook seems to have been largely unaware of it at the time) an old rival. General Nelson A. Miles had, to his chagrin, followed in Crook’s footsteps from the time they both were bright young Union generals in the Civil War, through the Sioux campaigns of the 1870’s, and the equally trying struggles for recognition and promotion amidst the narrow opportunities of the frontier army. Always Crook kept one jump ahead, and as Miles’ letters to his wife reveal, he had gradually developed an almost paranoiac jealousy of his somewhat older fellow officer. At last his great chance had come: Crook had been discredited, and it was up to Miles to succeed where Crook had not—with the whole country watching to see what would happen.

By May, 1886, Miles was in full command in Arizona. In the eyes of Crook’s loyal staff officers, most of whom were of course replaced, he was indeed a Johnny-come-lately, arriving on the scene when an absurdly small number of the hostile Apaches remained at large (to be exact, there were twenty-one men and thirteen women still with Geronimo). Nevertheless, it was a very big thing for Miles, and he made exhaustive preparations for the denouement. He reorganized his combat and supply forces, discharging nearly all of the Apache scouts—which must have pleased Sheridan—and distributing his troops so that there was hardly a ranch or water hole in Arizona or New Mexico that did not have a small detachment within easy call. One innovation, picked up from the British Army, did turn out to

By Miles’ own estimate, his men chased Geronimo more than two thousand miles in three months, and with highly impalpable results until the very end. Meanwhile Geronimo, to everyone’s consternation, had the insolence to strike back across the border into Arizona, expertly running a gantlet of half a dozen detachments of soldiers, and so closely pursued that his band, as Miles expressed it officially, “committed but fourteen murders” before they plunged into Mexico again.

What Miles’ troopers did succeed in doing—not surprisingly, since there were approximately five thousand of them—was to induce heavy fatigue in Geronimo’s little group. The chief himself was in his late fifties and perhaps decided that it was time to retire from the more athletic activities of his career. Nonetheless, when he finally gave up once and for all, on September 4, 1886, it was a negotiated surrender, and not a capture. Borrowing from the tactical book of General Crook, possibly with some embarrassment, Miles sent a pair of formerly hostile Apaches to seek out Geronimo’s camp and suggest a parley. This was achieved late in August, but only because Lieutenant Charles Gatewood, one of Crook’s best officers and one who knew Geronimo well, agreed to be the intermediary. Miles supplied him with an escort of troopers, but Gatewood knew what he was doing, and made his way to the meeting place, near Fronteras, Mexico, all alone. His offer to Geronimo’s band was simple: “Surrender, and you will be sent with your families to Florida, there to await the decision of the President as to your final disposition. Accept these terms or fight it out to the bitter end.”

Gatewood added something else: that many of their relatives had already been sent East—to Fort Marion, Florida, which the War Department judged to be sufficiently removed from Arizona to prevent further trouble. That news visibly affected the hostiles. They talked it over, and agreed to surrender to General Miles. After an eleven-day march, not as captives but still under arms and merely accompanied by American troops, they arrived at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona, where Miles joined them in a state of nervous excitement. His triumphal hour was near, but he was acutely aware that things could go wrong just at the last moment, as they had for Crook. He had never laid eyes on Geronimo before, and it may be supposed that he faced the famous

Geronimo, for his part, seemed to be relaxed, and even managed a humorous thrust at the moment of introduction. “General Miles is your friend,” said the interpreter. The Indian gave Miles a defoliating look. “I never saw him,” he said. “I have been in need of friends. Why has he not been with me?”

Miles had some of his men demonstrate the heliograph to Geronimo, sending a message to Fort Bowie and receiving a reply within minutes. If anything had been lacking to clinch the surrender, that did it, and on September 7, 1886, Miles was able to write to his wife, without undue modesty: “If you had been here you would have seen me riding in over the mountains with Geronimo and Natchez as you saw me ride over the hills and down to the Yellowstone with Chief Joseph. It is a brilliant ending of a difficult problem.”

There were many who thought the ending was not so brilliant, and George Crook was one of them. At Omaha, where he was now in command of the Department of the Platte, he heard that Geronimo and his braves had been sent by train to Fort Pickens, Florida, while their families went to Fort Marion, two hundred miles away. This was an outright violation of the terms of the surrender; and on top of that, 400 Chiricahuas at Fort Apache, who had remained loyal all through Geronimo’s last rampage, were summarily rounded up and sent off to Fort Marion also. Not exempted were many Apache scouts who had served Crook with absolute fidelity, and to the end of his days the General never lost his smouldering indignation at this treatment.

Crook did more than just smoulder. He spent much of his time between 1886 and 1890 endeavoring to win better justice for his former enemies and allies, who were not exactly thriving in the steaming climate of Florida. Malaria and other “white men’s diseases” took a lugubrious toll: even at the well-run Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, where many of the children were sent to be civilized, thirty of them had died by 1890. Early that year, Crook made a visit to Mount Vernon Barracks, near Mobile, Alabama, where the surviving Chiricahuas had been transferred for reasons apparently having more to do with the convenience of the government than their welfare. The news swiftly got around that “Chief Gray Wolf” had come to see them, and soon they were crowding about him—Chato, Chihuahua, Naiche, and the rest—eagerly shaking his hand and laughing with pleasure. Geronimo hung about the edge of the crowd, but Crook had never forgiven him for failing to keep his pledge in the spring of 1886, and would not speak to him. At the schoolhouse, where some of the children recited for the General’s benefit, the old chief made one last ploy, threatening unruly pupils with a stick, and looking to Crook for approval; but he got not a word.

On the

Yet it may be that even in death Geronimo was true to his reputation. An interested group of people at Fort Sill raised a simple but dignified monument over his supposed grave, and there it still stands on Cache Creek, part of the Fort Sill reservation. But one day in 1943 a soldier reporter for the Fort Sill Army News happened to interview an elderly Apache who had been commemorating old times with a bottle of whiskey. Out came an intriguing story. Geronimo was not where they said he was, the old Apache claimed. No: One night, not long after his burial, a small band of his former warriors went to the grave and spirited his remains away to a secret place, clear of the white man’s reservation. When this story was published, fervid denials came from several sources. But the elderly Apache just smiled and nodded. Geronimo, he insisted, got away in the end.