Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February 1964 | Volume 15, Issue 2

Authors: Frank Uhlig, Jr.

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February 1964 | Volume 15, Issue 2

The S.S. Virginius of New York, Captain Charles Fry, darted up from the Jamaica coast, bound for Cuba, which lay blue in the distance. It was November, 1873. As the ship crossed the brilliant Caribbean, the Spanish gunboat Tornado took chase and closed quickly. When the Spaniards boarded, they found the Virginius stacked high with arms for Cuba’s rebels, then engaged in another of their apparently endless insurrections against the mother country.

The captured ship was taken to Santiago, on Cuba’s southern shore. Forty-three of the passengers and crew were bound, lined up against a wall, and shot. The rest were saved only by the arrival of H.M.S. Niobe , whose captain insisted that the Spanish governor “stop that filthy slaughter.” For a time, war between the United States and Spain seemed unavoidable. President Grant ordered the fleet mobilized at Key West.

A marvelous collection of naval museum pieces gathered there. Eleven old wooden steam frigates and steam sloops, their decks lined with muzzle-loading smoothbores, their masts laden with canvas, made up the cruising force. Five iron monitors, hastily recommissioned, were towed down from the James and the Delaware, where they had been rusting since the Civil War. The fleet, which could maneuver only as fast as its slowest member, the steam sloop Shenandoah , puffed along at four and a half knots. (Spain had four modern seagoing ironclads which could make nearly three times that speed.) In the end, perhaps, it was well that the President turned the Virginius affair over to the State Department for settlement.

There were few who would have guessed that twenty-five years later an American fleet would litter the beaches of Cuba with the burned and blasted wrecks of Spanish warships; that another American squadron would do the same thing in the distant Philippines; or that a decade after those victories, the most powerful fleet of battleships ever to circumnavigate the world would fly American colors.

Two then-obscure young men were to play major roles in this transformation. One, the only midshipman ever to skip plebe year at Annapolis—who, ironically, was to write of his naval career, “I believe I should have done better elsewhere”—was in 1873 a quiet, austere, and unhappy officer in command of the U.S.S. Wasp , a captured Civil War blockade-runner performing odd jobs for the ramshackle fleet of the South Atlantic Station. The other was the asthmatic son of a wealthy New York City family, just back from a sojourn in Germany and preparing for a gentleman’s career

Meanwhile the nation soon forgot its Caribbean misadventure: there was much more urgent business at hand. The problems of Reconstruction, the surge of population toward the West, the burgeoning of new industries, the tips and downs of the stock market, labor troubles, the social upheavals of immigration, and the scandals of the Grant administration seemed to leave little time for overseas affairs—or for the needs of a neglected navy.

See more stories about the history of the U.S. Navy here

While the navies of the major European powers relied increasingly on armored ships driven by steam, the American Navy, which had pioneered in both fields and which had more recent battle experience than all the rest put together, cruised under sail, in wooden ships. (There was even a move afoot to make all navy captains pay out of their own pockets for whatever coal their ships burned.) The promotion process stagnated; an Annapolis graduate might still be a lieutenant at the age of fifty. To make matters worse, the office of Secretary of the Navy was filled throughout the 1870’s by political hacks. Grant’s appointee, George M. Robeson, apparently managed to feather his nest with some $320,000 of Navy Department funds; a few years later, Richard W. Thompson of Indiana, who served under Hayes, visited a warship and exclaimed with some amazement, “The damn thing is hollow!”

“By the year 1880 the navy had fallen to a pitifully low ebb,” noted Frank M. Bennett, the historian of the nineteenth-century American steam navy. “Repairs were no longer possible, for space for more patches was lacking upon almost every ship of ours then afloat.… A sense of humiliation dogged the American naval officer as he went about his duty in foreign lands; in the Far East, in the lesser countries along the Mediterranean Sea, and even in the sea ports of South America, people smiled patronizingly upon him and from a sense of politeness avoided speaking of naval subjects in his presence.” That year there were thirty-eight admirals on the active list (with commands afloat for but six) and only thirty-nine ships. It was a situation that openly invited ridicule. In an Oscar Wilde comedy written at the time, an American lady who despaired of her country because it had neither curiosities nor ruins was consoled with heavy irony because “you have your manners and your navy.”

But a change was in the air, though it would be a long time before the officers and men of our patchwork

The Rodgers board, apparently believing a serious question deserved a serious answer, urged that eighteen cruisers and fifty smaller ships be built at once—whereupon it was dismissed. Another board was appointed, which made recommendations that were less far-seeing but, for the moment, more practical. Following its suggestions, Congress provided for three steel cruisers and one dispatch boat, the latter a small ship useful for carrying messages.

Contracts for all four ships, the 4,500-ton Chicago, the 3,000-ton Atlanta and Boston, and the 1,500-ton Dolphin, were awarded to John Roach, a shipbuilder who was also a Republican wheel horse. In 1885 the first of the lot, the Dolphin , was completed; for months she lay alongside her pier, rakish in her standard navy black paint. But Congress and the Presidency had gone to the Democrats in 1884, and the Dolphin was rejected for an assortment of design and mechanical deficiencies. On the advice of friends in the Republican party, who perhaps thought they needed a martyr, Roach, instead of fighting the issue, went into bankruptcy. The Atlanta, Boston , and Chicago were taken over by the government half-built. Not until 1889 was the last of them completed and commissioned.

Eventually the Dolphin was accepted, and in 1888 she began a two-year cruise around the world. Men wilted inside her black steel hull as she passed through the tropics. Desperate for a remedy, her captain broke a century-old custom and painted his ship with white lead, thus cooling her interior by several degrees. The Navy Department copied his example; soon all new warships were coming out of their builders’ yards in white. They were quite dashing, with ram bows decorated by gilt scrollwork or American shields, and upper works painted yellow ochre, much like today’s Coast Guard cutters.

By the end of the decade the first of the Navy’s armored cruisers, Roach’s ships, were at sea, and more were being built. Gradually the old wooden fleet faded away. But American industry, though energetic and willing, had much to learn about building steel warships and supplying their needs. More important, no one in this country was yet competent to design a modem warship. The four ships that the unfortunate Roach built, for example, were all outfitted with a full set of sails in addition to reciprocating steam engines; the Atlanta and Boston were fitted with engines and boilers of a type already outmoded.

Disappointed with American plans, the Navy Department

Then, in 1890, Congress authorized the nation’s first real battleships. The appropriation called for “seagoing, coast-line battleships,” a grand contradiction, for a seagoing ship had to be a deep-draft, high-freeboard vessel with lots of room for coal, while a coast-line ship neither needed nor gained from any of these characteristics. At any event, the Navy took advantage of the confusion to build three of the finest warships of the age: Indiana, Massachusetts , and Oregon . Powerfully armed and heavily protected, they made only one concession to the “coast-line” part of the law: they were designed with a low freeboard.

The completion of the Indiana -class battleships, each weighing over ten thousand tons and armed with four 13-inchers, eight 8-inchers, and a variety of smaller guns, would signal a break with the past that was, in its own way, as revolutionary as the building of the first ironclads in the Civil War. Until now, Americans had imagined naval combat in terms of the heavyfooted, short-legged monitors guarding the home shores while swift cruisers like the newly commissioned Columbia and Olympia shot out of the mist to burn enemy—which naturally still meant English—merchant shipping. This was the formula that had worked to a degree in the special circumstances of 1812, when most of England’s great navy had been occupied fighting the French. Under more normal conditions of war, however, it was likely to fail, as it had failed the Confederates in 1861. History showed that the chief business of a navy at war is to destroy or at least lock up the enemy’s fleet. But big ships had always been needed to accomplish this end, and in 1890 that meant steel battleships.

Such was the persuasive argument of Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, the sea-going intellectual who had been elevated from the humdrum of routine duty to head the newly established Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. In 1886, his first year in the post, Mahan had delivered a series of lectures which, four years later, appeared as a book, The Influence of Seapower upon History, 1660–1783 . Though it was essentially a historical work, its implications were much broader, and it had a widespread influence both here and abroad. As the historian Louis M. Hacker has written:

…it was translated into all the important modern languages; it was read eagerly and studied closely by every great chancellory and admiralty; it shaped the imperial policies of Germany and Japan; it supported the position of Britain that its greatness lay in its far-flung empire; and it once more turned America toward those seas where it had been a power up to 1860 but which it had abandoned to seek its destiny in the conquest of its own continent.

Mahan’s message—which in his day seemed revolutionary—was that a strong navy was the key to national power and security. And yet, only with the greatest reluctance did the Navy accept the formulations of this unsociable officer with the scholarly mind. (“It is not the business of a naval officer to write books,” one hard-shell admiral once reminded Mahan when he asked that his next sea tour be put off until he had completed the volume he was then working on.) Gradually, however—and Mahan’s influence is undeniable—the Navy underwent a fundamental transformation: an essentially provincial organization would one day become a sophisticated professional service which knew how to think in terms of war waged across the oceans and around the globe.∗∗ Even in World War II Mahan’s studies were influential in American naval thought, as Secretary of War Henry Stimson discovered when he frequently found himself confronted by that “dim religious world, in which Neptune was God, Mahan his prophet, and the United States Navy the only true Church.”

If the Indiana-class battleships were models of advanced design, many of the ships which entered service in the nineties were obsolescent curiosities. Hardly any two were alike. There was the bizarre Brooklyn, with her huge beaked bow, tumble-home sides, and three slender smokestacks soaring a hundred feet above the furnace grates. There was the long, narrow Vesuvius , which fired shells filled with dynamite from three 15inch pneumatic guns angling out of her fo’c’sle deck, and the Katahdin , armed with a formidable ram upon which she was to impale the foe. So that she might be invisible against her sea background she was painted green, and she could submerge till the deck was awash. Alas! She was too slow to catch any vessel with the wit to get out of the way.

Then there were the low, flat monitors—”about the shape of a sweet potato which has split in the boiling,” wrote a future admiral, William S. Sims, who served for a time in one of them. Six in number, they had raftlike hulls little different from that of John Ericsson’s original Monitor of 1862. If one can accept the faintly cannibalistic idea of one ship absorbing another and quietly assuming her victim’s identity, he can trace the history of most of these craft back to the Civil War.

The old

In spite of this lingering abundance of floating oddities and antiques, it was not a bad fleet, though hardly in a class with the navies of the major European powers. Nor did there seem any likelihood that it would be for years to come. As Admiral Bradley Fiske wrote, years later:

there was absolute conviction in the minds of everybody that the United States would never go to war again, and that our navy was maintained simply as a measure of precaution against the wholly improbable danger of our coast being attacked. It was not considered proper for a nation as great as ours not to have a fine navy; but the people regarded the navy very much as they regarded a beautiful building or fine natural scenery: a thing to be admired and to be proud of, but not to be used.

But a test of America’s new navy came sooner than anyone expected. Affairs in Cuba had not improved since the days of the Virginius incident. In February, 1898, while on a visit to Havana, the battleship Maine blew up, killing 262 men. Spain frantically disclaimed responsibility (the cause of the explosion has never been satisfactorily determined) but to no avail. Two months later, the United States declared war. The fleet went into dull gray paint and loaded ammunition—which had been provided by the foresight of the energetic young New Yorker who was Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodcre Roosevelt. His duty done, Roosevelt resigned to get into the fight with his own mounted regiment of cowboys and college boys.

In Europe, only the British favored an American victory, but they were not hopeful. As Commodore George Dewey led the Asiatic Squadron out’of Hong Kong, the prevailing opinion of the Royal Navy officers was that the Americans were “a fine set of fellows, but unhappily we shall never see them again.”

It didn’t work out that way. Dewey, with four cruisers, two gunboats, a Coast Guard cutter, and two supply ships, entered Manila Bay late in the night of April 30, exchanged a few shots with the forts

The Philippines, however, was a side show; Cuba remained at all times the chief theatre of war. By April, the Navy’s half-dozen big ships in the Atlantic had been concentrated at Key West, and the Pacific Station’s only battleship, the Oregon , was pounding up the east coast of South America at a steady eleven knots, en route to the Florida base.

Meanwhile, somewhere in the Atlantic, Rear Admiral Pasqual Cervera was at sea with the main Spanish squadron—four big armored cruisers accompanied by three torpedo boats. Panicking, the East Coast demanded naval protection. To give the appearance of a defense, Civil War monitors were hastily reconditioned and manned with naval militiamen. The public wanted more. So, despite Mahan’s dictum that the battle fleet should never be broken up, it was. One half of our big ships were formed into the so-called Flying Squadron under Commodore Winfield Scott Schley in the Brooklyn and ordered north to Norfolk, to catch Cervera if he should try to shell coastal cities or beach resorts. It was an unwise move, for both the Flying Squadron and the ships remaining at Key West under Rear Admiral William T. Sampson in the armored cruiser New York were now outnumbered by the Spaniards. Luckily, however, Cervera had neither fuel nor ammunition to waste on civilian targets.

In time the Spanish admiral and six of his ships reached Santiago, on Cuba’s southern coast, where they stopped for coal. After some hesitation, the North Atlantic Fleet, once again united under Sampson, gathered at the entrance to Santiago’s little harbor and dared the foe to venture out. When nothing happened, a naval constructor named Richmond P. Hobson and seven volunteers attempted to trap Cervera by sinking an old merchant ship in the middle of Santiago’s narrow channel. Running in at night under fire from the enemy’s ancient shore batteries, they sank the ship, but she went down lengthwise rather than athwart the channel, and the way remained open.

Next the Army tried to drive Cervera out. In the second half of June some 17,000 troops were landed at Daiquiri, about halfway between Santiago and the recently captured base at Guantanamo Bay. Fighting not only a well-entrenched, though hungry, enemy but heat and tropical disease, the outnumbered American army also failed. The commanding general called upon Admiral Sampson to dash through the enemy’s minefields and collar the Spaniards; he refused.

Prodded from Madrid, the reluctant Spanish admiral headed out to sea—and provided the American Navy with another great morning. The Americans, led by Sampson’s second-in-command, Commodore Schley, destroyed all of Cervera’s ships without losing a single ship of their own; only one man was killed, a yeoman on the Brooklyn . When Admiral Sampson heard the gunfire, he turned the swift New York around and crowded on all speed, but he arrived too late. His report to Washington, “The fleet under my command offers the nation as a Fourth of July present the whole of Cervera’s fleet … ,” precipitated a bitter wrangle with Schley that went on for years.

Nonetheless there was glory enough for all. Everyone was gallant, officers shouted heroic phrases (“Don’t cheer, boys, the poor devils are dying,” cried Captain Jack Philip of the Texas ), and the scene was bright with flying flags and flaming guns. After the battle the victors risked their lives to rescue their recent enemies from exploding ships, sharks, and Cuban guerrillas on the beach; captured Spanish officers were taken to Annapolis, where they were treated as gentlemen-heroes.

“A splendid little war,” wrote an exultant John Hay from London, and most would agree. Cuba was free after four centuries of Spanish rule and now we had colonies of our own: Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. The Navy had become immensely popular. Congress provided for so many new ships that the nation’s shipyards were clogged for years.

Not everyone, however, was as self-satisfied as Hay. Within the Navy serious questions arose about American strategy (splitting the Flying Squadron from the rest of the fleet), tactics (Santiago was a captains’ battle with no direction from Commodore Schley), and gunnery (firing at ranges of a mile or two, only 1.3 per cent of the shots hit home). Perhaps the performance was no worse than anyone else’s might have been. In any event it was better than the Spaniards’, and that was enough for that war.

In September, 1901, Theodore Roosevelt, a political nonconformist whom Republican chieftains had tried to bury in the Vice Presidency, unexpectedly became President when William McKinley was assassinated. For the seven and a half years that Roosevelt was in the White House, the Navy toiled and prospered. Roosevelt was a zestful player at world power politics. He believed not only that “a great country must have a foreign policy,” but also that “there is some nobler ideal for a great nation than being an assemblage of prosperous hucksters.” The Navy became his chief means for executing his views on foreign policy.

Tiny gunboats commanded by officers fresh from Annapolis cruised, ready for battle, up and down the Philippines and far up the pirateridden rivers of China. Others roamed the

This 1887 engraving from Harper’s Weekly , based on a drawing by Frederic Remington, is titled “The Last Aboard”—referring, of course, to the acrobatic fellow in the blue uniform and leg irons who is being gently assisted to the deck of a U.S. Navy man-of-war. Some siren song of the mainland has obviously smitten him—but a few days in the brig will cure all that. Commenting on this tableau, an anonymous Harper’s moralist spoke of the “certain human tendencies” in sailors “which, for all that one can see, will last to the end of things nautical … In the case of the sailor whose return is represented in the picture … the indisposition to resume the humdrum of a seafaring life is most marked.… His mates understand that he means no offence to them personally by being burdensome, and that his balky behavior is directed merely against the general system of ship discipline, which, on such an occasion particularly, seems very harsh and grinding to him.

“The types of sailors represented,” the writer concluded, “are taken from Uncle Sam’s navy, and may be seen in life just at present at the Brooklyn Navy-yard, where, though satisfactory results have attended the energetic temperance crusade conducted by the worthy chaplain of the Vermont , the backsliders are sufficiently numerous to supply many originals for the subject of our illustration.”

In November, 1903, negotiations with Colombia for a ship canal through the Isthmus of Panama failed. Not long after, that province flared into revolt. When loyal troops arrived at Colon they found the U.S. gunboat Nashville in the harbor and her landing party ashore, effectively blocking the restoration of Colombian authority. Roosevelt quickly recognized Panama as an independent state, and soon had his canal site.

The gunboats may have borne the White Man’s Burden, but they did so under cover of the big ships. Twice war seemed imminent: in 1901, with Germany, when it threatened to slice off a portion of Venezuela in payment for a bad debt, and again, in 1907, with Japan. Twice the President mobilized his battle fleet, and twice the war threat vanished.

During Roosevelt’s administration, the American Navy became, for a time, the second most powerful in the world, boasting more than forty big armored ships—compared with seven during the war with Spain. Only England had more heavy ships (ninety-eight in 1908), while France came third with thirty-three; Germany had thirty-two, and Japan twenty-two. (Russia, long in third place, had been humiliated by the Japanese in 1904–05 and for many years would no longer be counted among the great sea powers.) Germany, Japan, and the United States were on their way up; indeed, after Roosevelt left office in 1909, Germany passed the United States. France was steadily losing ground.

Moreover, from 1905 on, for the first time

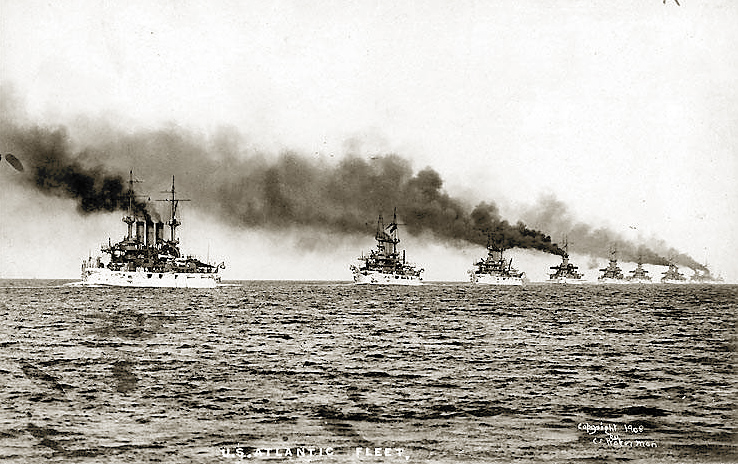

Then, toward the end of his second term, Roosevelt, always the master showman, came up with the most dramatic stroke of all. With the Japanese war problem still before him, he announced that he would send sixteen of his best battleships from the Atlantic to the Pacific in a show of strength. Dazzling in its white paint, the fleet sailed from Hampton Roads, Virginia, in December, 1907, with Rear Admiral Robley (“Fighting Bob”) Evans leading in his flagship, the Connecticut . The first night out, Evans had a surprise for his 15,000 officers and men: ”… after a short stay on the Pacific Coast, it is the President’s intention to have the fleet return to the Atlantic Coast by way of the Mediterranean.” They were going to steam around the world. The voyage of the “Great White Fleet,” which was to take it 45,000 miles in fourteen months, had begun.

As the Panama Canal was far from finished, the ships made the long first leg of their voyage by way of Rio, the Strait of Magellan, and the west coast of South America. The fleet’s first foreign port was Port of Spain, Trinidad, where it was received with indifference, for the arrival of the Americans coincided with the opening of the horse-racing season. Their reception in Rio was much better. Officers and men alike had a good time. Perhaps the most noteworthy outcome of the occasion was the birth of the Shore Patrol. Evans was determined that his men, let loose in a glittering foreign capital, would be neither the cause nor the victims of trouble. The men did well by their admiral, and the city by the men. Even so, the Shore Patrol proved itself so effective that it has now become an institution, in evidence wherever a naval base is located or in whatever port a U.S. man-of-war may visit.

Buenos Aires also wished to entertain the Americans, but its ship channel was too shallow, and the fleet passed on. Not, however, before it had received a graceful salute, far at sea, from a squadron of neatly handled green-hulled Argentine cruisers. Farther south the fleet stopped at Punta Arenas on the Strait of Magellan, where the stores advertised special prices for the Americans. They were special, too. Twenty-five-dollar fox skins were available at forty, and seal, normally sold at fifty dollars, could be had for seventy-five.

The last part of the passage through the mountainrimmed Magellan Strait was made through fog so thick that one could see neither the ship 400 yards ahead nor the one 400 yards astern—the interval

Now the white column steamed north and at Valparaiso Bay saluted the President of Chile. Less than twenty years earlier Evans, in a gunboat, had been involved in that very same bay in an unpleasantness which nearly caused war between Chile and the United States. Two U.S. Navy men had been killed in a riot arising from a barroom brawl, and it was largely Evans’ tact which prevented a major incident. But cordiality was the order now—as it was at Callao, the seaport to the Peruvian capital, Lima, where the fleet was entertained by bullfights. It continued north to Magdalena Bay, Mexico. There, by arrangement with the Mexican government, the Americans were able to spend a month at target practice, drill, and sports. Then they went on to California, where Admiral Evans, painfully ill with rheumatism, gave up his command.

After the men were banqueted at every port from San Diego to Seattle, Evans’ replacement, Rear Admirai Charles S. Sperry, took the fleet to sea again, heading out across the Pacific in the beginning of July. The first stop was Honolulu. Chief turret captain Roman J. Miller of the Vermont , visiting nearby Pearl Harbor, found that though it was yet undeveloped, it was “from a naval point of view, a very important place.” Leaving the Hawaiian Islands, the ships proceeded on a leisurely roundabout voyage, with stops at New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, and Japan.

The Japanese, who only a short time before had been threatening war, received their white-hulled visitors with “cordiality … amounting often to actual frenzy,” as one participant remembered. The Americans did more than enjoy the cordiality. Observing the Japanese fleet in dark war paint, many officers recommended that our ships also be painted for war at all times. To leave the ships white until strained relations occurred with another country and then to change their color would be, as one naval officer has pointed out, “an overt act that might precipitate the very enemy action that the diplomats might otherwise be able to forestall.” The recomended change was put into effect within a few months, and our ships have worn gray in one shade or another ever since.

After Japan, the fleet was temporarily split—for target practice off Manila and on the China coast. Then, entering the Indian Ocean, the ships steamed for home. The long passage was broken only by a visit to Ceylon; there the American sailors from the farms of Kansas and Georgia caught glimpses of native villages hidden away in groves, far up in the mountains, and tea or rubber plantations. When the fleet arrived at Suez, in January, 1909, word came of an earthquake at Messina, in Sicily, which had killed 60,000 people. Help was desperately needed. One ship from the fleet was

On February 22, 1909—Washington’s Birthday—the Great White Fleet steamed home at last, to be welcomed at Hampton Roads by T. R. in the presidential yacht Mayflower . The occasion marked his last significant accomplishment as Chief Executive; ten days later, he left the White House for good. It was an impressive end to a notable presidential career; in his autobiography Roosevelt could write with justifiable pride that the voyage of the Great White Fleet was “the most important service I rendered peace.” As he said in a speech to Admiral Sperry and his men:

You have falsified every prediction of the prophets of failure. In all your long cruise not an accident worthy of mention has happened.… As a war machine, the fleet comes back in better shape than it went out. In addition, you, the officers and men of this formidable fighting force, have shown yourselves the best of all possible ambassadors and heralds of peace.… We welcome you home to the country whose good repute among nations has been raised by what you have done.

The accomplishments of the Great White Fleet had been numerous indeed. In his report for 1909 the Secretary of the Navy stated that the cruise “increased enlistments and enabled the Bureau of Navigation to recruit the enlisted force to practically its full strength,” a pleasing development in a period when few American boys thought seriously of joining the Navy. Moreover, the Secretary was able to report, “There has been a gratifying decrease in the percentage of desertions, which has dropped from 9 to 5½ per cent during the past year.”

The officers and men learned a great deal, too. They learned how to get the greatest economy out of their engines, the most mileage per ton of coal. Because they had no navy yards handy, they learned that to a great degree they could maintain their ships themselves. They learned to place their ships accurately on station during tactical drills and battle exercises, and to keep them there. At Magdalena Bay, early in the cruise, Admiral Evans said to one of his captains, “I hope your officers have learned something …” The captain replied, “Thirteen thousand miles at four hundred yards, night and day, including the Strait of Magellan; yes, they have learned a lot!”

More important, the cruise of the Great White Fleet demonstrated beyond question that the United States was now a world power. Those battleships, as they dipped their curved beaks into the rollers of the Pacific, the calm stretches of the Indian Ocean, and the white-flecked Mediterranean, were dramatic evidence of the radical change of course which this country, however unwitting and unwilling, had now taken.