Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February 1964 | Volume 15, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February 1964 | Volume 15, Issue 2

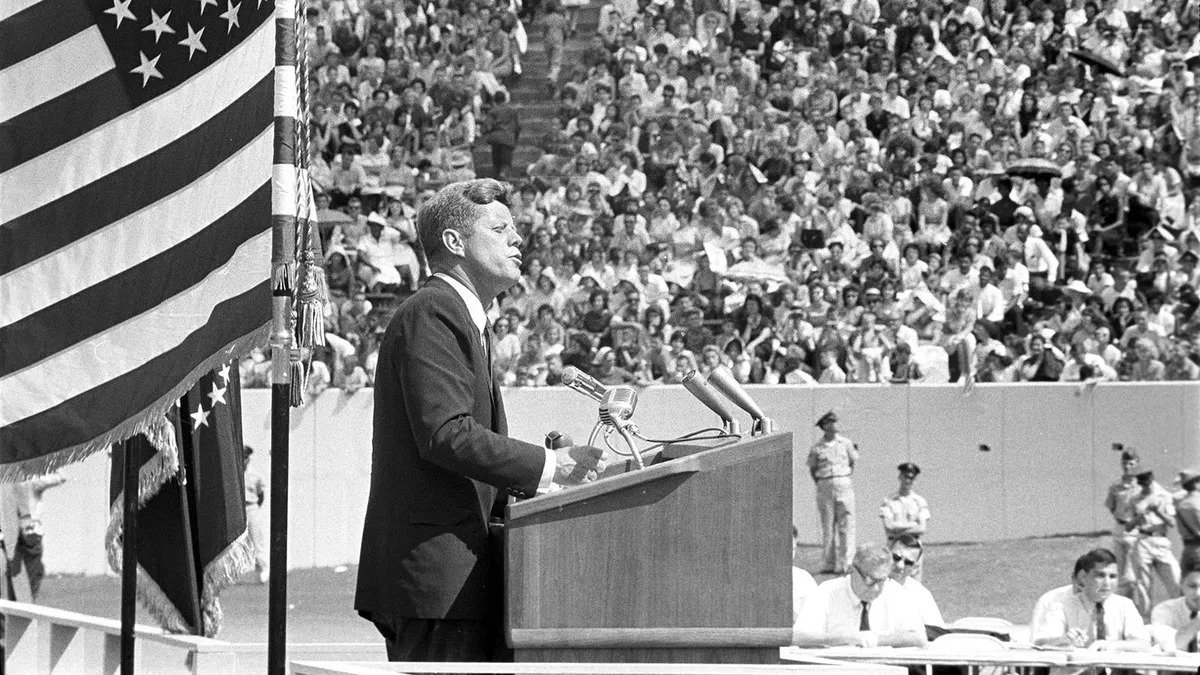

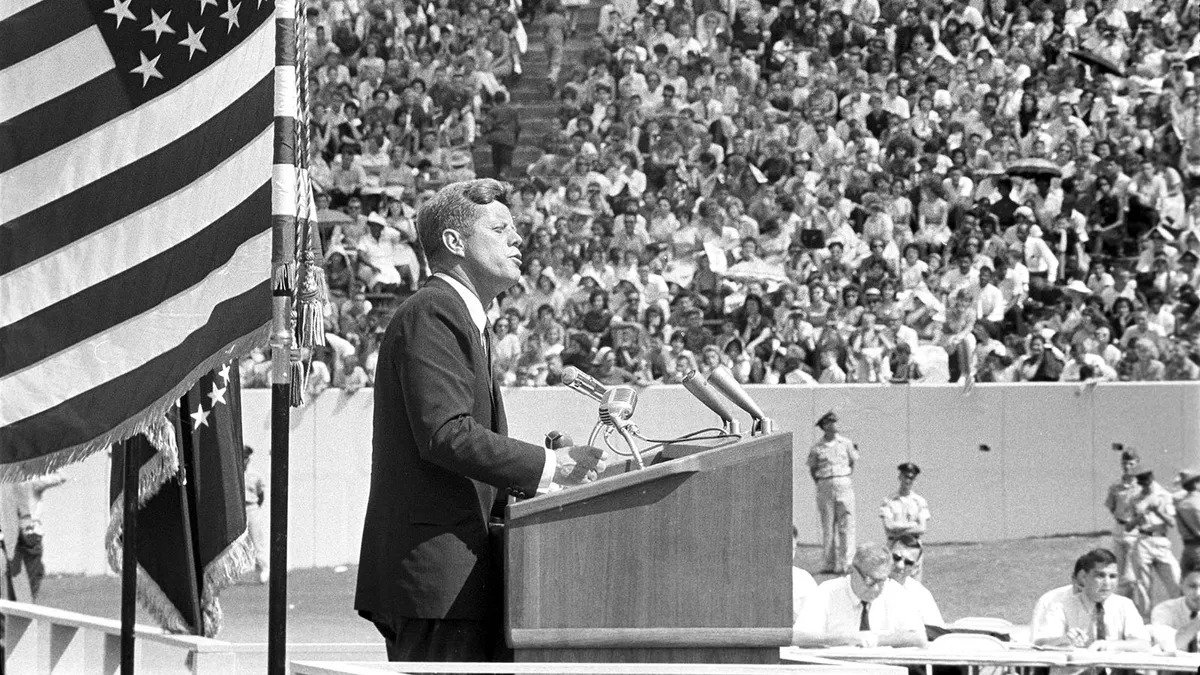

President Kennedy, who now so prematurely and tragically belongs to history, not only made history himself but wrote it with depth and eloquence. His heightened perceptions of it pervaded his actions and his public papers. Astonishingly in so busy a man, he could even find time in the White House to keep up his intellectual interests, to read good books, and to write prefaces and occasional pieces. Last year he was kind enough, at our request, to furnish an introduction to a sixteen-volume set of books that we created, The American Heritage New Illustrated History of the United States. It would have been easy enough to muster a few bland platitudes, and dash them off, as so many people do in such circumstances, but that was not his way. Instead he sent us this moving essay. It compresses into brief compass much of the philosophy that animates the historical profession. We are proud to reprint it here.

—Oliver Jensen, Editor, American Heritage Magazine

There is little that is more important for an American citizen to know than the history and traditions of his country. Without such knowledge, he stands uncertain and defenseless before the world, knowing neither where he has come from nor where he is going. With such knowledge, he is no longer alone but draws a strength far greater than his own from the cumulative experience of the past and a cumulative vision of the future.

Knowledge of our history is, first of all, a pleasure for its own sake. The American past is a record of stirring achievement in the face of stubborn difficulty. It is a record filled with figures larger than life, with high drama and hard decision, with valor and with tragedy, with incidents both poignant and picturesque, and with the excitement and hope involved in the conquest of a wilderness and the settlement of a continent. For the true historian—and for the true student of history—history is an end in itself. It fulfills a deep human need for understanding, and the satisfaction it provides requires no further justification.

Yet, though no further justification is required for the study of history, it would not be correct to say that history serves no further use than the satisfaction of the historian. History, after all, is the memory of a nation. Just as memory enables the individual to learn, to choose goals and stick to them, to avoid making the same mistake twice—in short, to grow—so history is the means by which a nation establishes its sense of identity and purpose. The future arises out of the