Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2010 | Volume 60, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2010 | Volume 60, Issue 1

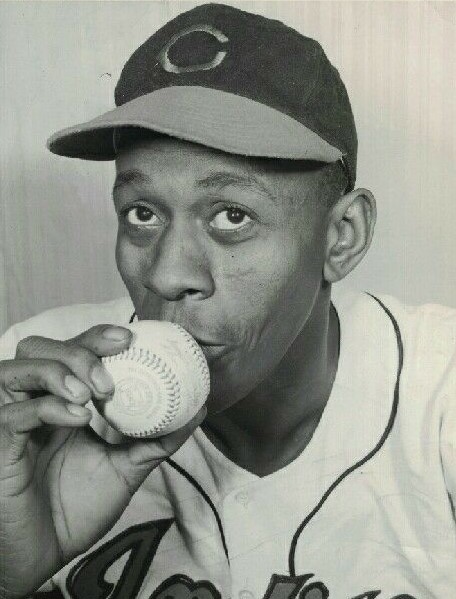

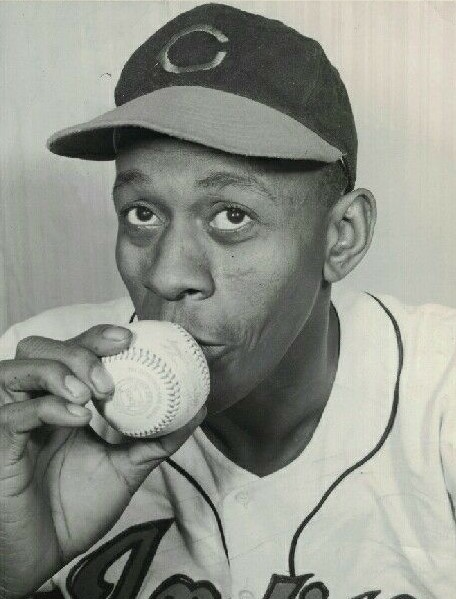

Leroy “Satchel” Paige, arguably the greatest pitcher ever to throw a baseball, was as green as a big league infield that April day in 1926 when he joined his first professional team, the all-black Chattanooga White Sox. Everything he owned—a couple of shirts, an extra pair of socks, underwear wrapped in an old pair of pants—still fit into a brown paper sack, the same as it had eight years earlier, when he was sentenced to the Alabama Reform School for Juvenile Negro Law-Breakers.

That was a good thing, because Satchel still could not afford a suitcase. He rented a room in a flophouse at the royal rate of two dollars a week. No sooner did he collect his first five dollars than he headed to the pool hall where a pair of sharks let him win a few games, then ran the table when the betting began. “I always figured I was pretty good at nine-ball and eight-ball,” Satchel told an interviewer decades afterward, “but those sleepy-eyed Chattanooga sharpies played me like the biggest fish in the Tennessee River.”

He looked like a rube on the diamond, too. His new uniform hung limply over his six-foot-three-inch, 140-pound frame. Street shoes with spikes nailed to the bottom had to suffice until the team could come up with regulation cleats large enough to fit his “satchel-sized” 11 feet. The one pitch he knew was an overhand fireball, so his catchers could dispense with signs; hitters knew it would be all heaters all the time. They quickly learned that while Paige was fast, he also was wild. Worst of all, he was swaggering. He resisted offers of coaching and crowed to his receivers, “Hold the mitt where you want it. The ball will come to you.”

What saved him was a willingness to work hard and a mentor as hardboiled as Alex Herman, a former semipro player. Lesson one was location, location, location: getting the ball over the plate every time. The key to control like that was practice. Herman lined up empty soda pop bottles behind home plate; Satchel worked at knocking them down, mornings before other players got to the field and evenings after they left. Herman knew there was something magical about this rookie righthander. His talent traced back to his hometown streets of Mobile, Alabama, where he fired rocks with enough power and precision to bring down a bird or a rival gang member. He learned to play at reform school and could pitch hard and sure enough to drive 10-penny nails into a plank set up behind home plate. The coach saw, too, that unless his raw gifts were refined, Satchel would stand little chance in a Jim Crow America where baseball, like every institution that mattered, was split into white and black worlds. “It got,” Satchel recalled, “so I could nip frosting