Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2009 | Volume 58, Issue 6

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2009 | Volume 58, Issue 6

In May 1862, two months after the ironclads USS Monitor and CSS Virginia (formerly the USS Merrimack) fought to a draw in Hampton Roads, Virginia, President Abraham Lincoln traveled south from Washington on a revenue cutter to visit the Army of the Potomac, intending to prod his recalcitrant general, George B. McClellan, into action. The president took with him Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, and General Egbert Ludovicus Viele, who had recently returned from the capture of Fort Pulaski off Savannah.

Lincoln’s destination was Fort Monroe, the largest and most powerful of the forts constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers between 1819 and 1834 as part of the Second System of coastal fortifications. The fortress had remained in Union hands despite its location in Virginia because Maj. Gen. John E. Wool had quickly reinforced it while the lame-duck James Buchanan administration had dithered over Fort Sumter. Since then the massive fortress at the tip of the peninsula formed by the York and side of the Confederacy, for it protected the Union anchorage in Hampton Roads.

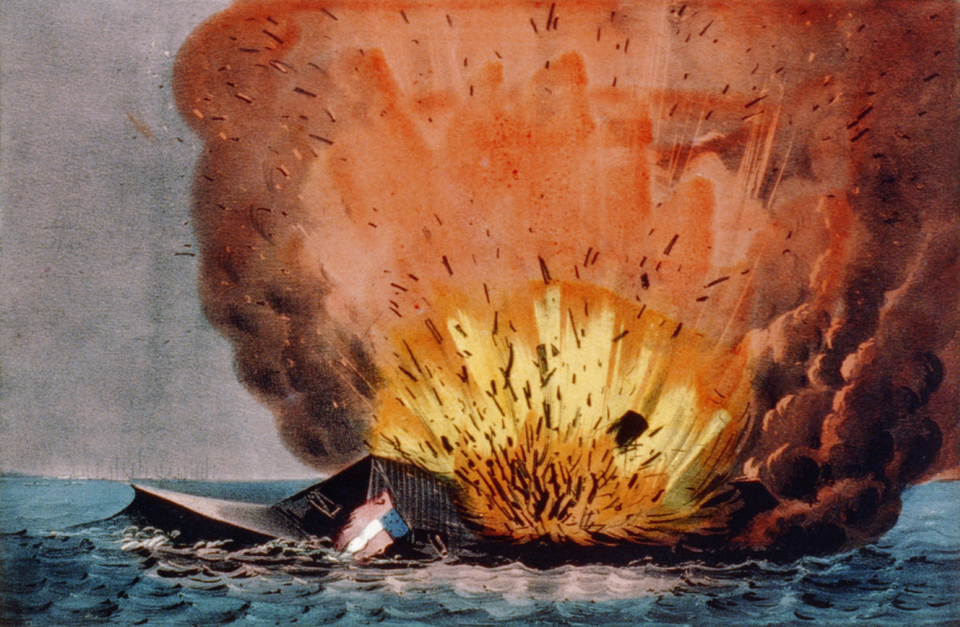

Lincoln and his party spent the night aboard the USS Minnesota, flagship of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, from whose broad deck the next morning, May 7, 1862, he viewed the fort and the half-dozen imperious warships at anchor, plus the intriguing form of the Monitor 's “cheesebox on a raft” stump of a turret. That turret, only 22 feet across, was the only part of the Monitor that showed from a distance, making the warship seem insignificant next to the others, including the huge side-wheel steamer Vanderbilt, recently reinforced with an iron-plated ram to enable it to contend with the feared rebel ironclad that Lincoln and all other Union officials continued to call the Merrimack. That vessel’s rampage on March 8 had destroyed two Union warships and greatly frightened the capital, leading some (including Secretary Stanton) to believe that the dreaded ironclad would steam unchallenged up the Potomac and lay waste to Washington.

The Blockading Squadron’s commander, Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough, pointed out to the president the pertinent military features of the roadstead, including the scene of the famous ironclad action and the rebel batteries that were clearly in sight at Sewell’s Point. Lincoln studied these and asked why the Navy tolerated their continued presence. To this, Goldsborough had no good answer, and he agreed to organize a “demonstration”—a kind of reconnaissance in force—to test them. Lincoln had come