Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

October 1960 | Volume 11, Issue 6

Authors: Louis W. Koenig

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

October 1960 | Volume 11, Issue 6

“If the manner of it be not perfect, it is at least excellent,” Alexander Hamilton once said of the machinery of the Constitution for electing the President and Vice President of the United States. In making this statement, Hamilton, for all his brilliance, was either committing an egregious error or engaging in eighteenth-century Madison Avenue encomium. On the basis of historical experience, it can reasonably be contended that the system of presidential election is anything but excellent, that it is in actuality a morass of complexity, indirection, and ambiguity. Nothing indeed could have been more expertly contrived to thrust the nation into periodic crises of uncertainty and strife.

The Constitution establishes the electoral college system to govern the President’s selection, and provides further means ol choice when that system bogs down in inconclusive result. But it grants the federal government only limited authority over its most important election, that of the President: critically significant powers repose in the states. My express or implicit constitutional authority, federal statutes specify the date of election day, determine when the electors are to meet and cast their ballots, and establish the procedure for counting those ballots in Congress. But at the same lime, the Constitution authorizes the states to decide how the electors are to be chosen and their electoral vote cast. State laws also regulate the conduct of elections, including the presidential contest, and political activity carried on within their borders. This authority and autonomy invite wide variation from state to state in the method, honesty, and freedom of federal elections.

In sanctioning this division of powers, the Constitution leaves elementary and crucial questions of procedure unanswered and permits the most outrageous eventualities to materialize. If, let us say, two conflicting sets of electoral votes are returned by a given state, who shall decide which set is to prevail? The Constitution provides no solution.

Consider another likely untoward instance. A candidate who receives on election day a majority of the popular vote cast may not, under the Constitution, necessarily become President—it he fails to secure also a majority of the electoral vote. The utter contradiction of this state of affairs with the most elementary principles of democracy is self-evident: the majority popular will can be denied.

It was to the great misfortune of the United States that both these forbidding eventualities actually occurred in a single election, under circumstances so confused and so acrimonious that they brought the country to the very edge of civil war.

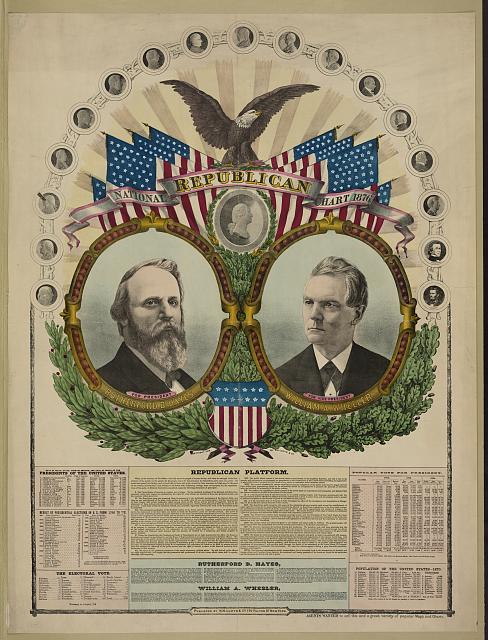

The occasion was the presidential contest of 1876,

The country, already surfeited with crises of the most formidable sort, could ill-afford another. The South was still wallowing in the slough of Reconstruction, although a decade had elapsed since the close of the War Between the States: a depression, which had commenced in 1873. was at its worst, and unemployment at its peak; upon the outgoing Grant Administration crashed wave alter wave of disclosure of immoralities and policy misadventures. The country could bear no more.

By sheer good luck, the principals in the disputed election were cautious, unsensational men of patriotic instincts. Governor Tilden, a wealthy, cold, secretive, sixty-two-year-old corporation lawyer totally without eloquence or personal magnetism, was incurably dilatory. “He postpones too much and waits too long,” the New York Tribune despairingly said of him. “He rides a waiting race.” To Martin Van Buren, who had intimately observed his career for thirty years, Tilden “was the most unambitious man he had ever known.” Governor Hayes was an exemplary solid citizen. Brigadier general in the Civil War, veteran of a decade of state and congressional politics, he was little known nationally. “He was not a leading debater or manager in party tactics,” a fellow congressman said of him, “but was aways sensible, industrious, and true to his convictions.” Hayes had another talent that stood him well: the gift of prophecy. Two weeks before the election he wrote musingly in his diary of the hazards that confronted him in the election. “Another danger is imminent,” be stated; “A contested result.”

The first returns on election night, November 7, indicated Tilden victory in a close rate. The New Yorker had carried his own state. Connecticut, Indiana, New Jersey, and apparently the Solid South. In an era innocent of radios, telephones, and voting machines, however, only fragmentary returns were available from the West, the far South, and the back counties of most states.

Nevertheless, Democrats across the land were confidently and jubilantly celebrating the victory, and newspapers were proclaiming it. In Tilden’s own New York City, the Tammany wigwam on Fourteenth Street resounded with songs and huzzas, and soon after midnight joy broke all bounds when a message arrived from Tilden himself hailing the glorious triumph. Meanwhile, at the Governor’s comfortable mansion on Gramercy Park, the congratulatory messages were pouring in. “Hully for us!” “Hey! Sammy!” “Reform at last!” and so they went.

In Columbus, Ohio, all was gloom. Governor Hayes, surrounded by his family and a few old friends, received the election news from a procession of telegraph messenger boys trooping through his

But not everyone was so resigned. At the New York Times, an editorial council in a dirty office littered with proof sheets was charting the position to be taken in commenting on the election in the impending morning edition. The interest of the Times editors had been aroused by an inquiry from D. A. Magone, the New York State Democratic chairman, and Senator William Barnum of Connecticut, concerning the status of the election returns, nationally. Barnum also asked specifically about Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. In poring over their check lists of voting data by states, the bitterly anti-Tilden managing editor, John C. Reid, and his associates noticed that only the most fragmentary information was on hand from the three states Barnum had mentioned, the only ones still under Republican control in the South. Even more significant, the Democratic managers in those states had not sent in their reports of the popular vote cast—the usual basis of party daims to the electoral vote. In light of the unexplained Democratic silence the Republicans might conceivably, by the wildest conjecture, claim those three slates, although ultimately any suchclaims would have to be vindicated be the official count of the popular votes.

The Times editors, all solid realists, were not expecting any sudden dramatic upsurge of votes for Hayes in the unreported southern returns. Their hopes turned on one possibility: that in each of the three states in question the official canvassing boards could, if their ethical sense was numb enough, manipulate a popular majority for Hayes that in turn could be transformed into electoral votes. Indeed, as computed by Reid and his now thoroughly agitated colleagues, the twenty electoral votes of Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina, when added to the 165 already attributed Io Haves, would give the Republican candidate 185 electoral votes (the bare majority required by the Constitution for election) to 184 for Tilden.

The editors decided that the headlines of the morning edition should declare, “Results still Uncertain. A Solid South, except Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina for the Democracy.” Being a practical man of action, Editor Reid also saw the necesssity of forestalling the Republican national organization from conceding the election to the Democrats until he had had a chance to communicate with key Republicans in the three doubtful states. He raced to the national party headquarters at the Fifth Avenue

Thereupon Reid returned to his office to prepare the November 9 edition of his paper, which proclaimed unqualifiedly that “Hayes has 185 electoral votes and is elected.” The Republican national chairman made an identical assertion of victory. South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana were put in the Hayes column even though the Associated Press on the very same day was reporting Democratic claims of having carried Louisiana by 20,000 votes.

Among the Republicans who immediately entrained for Florida were E. F. Noyes, Senator John Sherman, and Congressman James Garfield, all Ohioans and close friends of Hayes; Senator John A. Kasson of Iowa; General Lew Wallace, romantic novelist and future author of Ben Hur; and General Francis C. Barlow, President Grant’s personal representative. Soon similar battalions of important citizens of both political parties—“visiting statesmen,” the newspapers called them—were descending upon all three southern states. Their mission was to watch out for their party’s interests locally and to gather evidence for presentation to the state canvassing boards and eventually to courts and congressional investigating committees.

President Grant was not confining himself to the dispatch of personal agents. On November 10, he ordered General William T. Sherman to alert all troops in Louisiana and Florida to any attempted molestations of the boards of canvassers in the performance of their duties. Additional companies were sent to likely trouble spots in both states. South Carolina was already well-stocked with federal troops.

The friends of Mr. Tilden, and probably Mr. Tilden himself, were sorely distressed by the President’s military moves. August Belmont’s alarums were typical, Grant’s military order, he was convinced, had erected an armored façade behind which the canvassing boards could count Tilden out of the Presidency. In Columbus, the prevailing mood was no happier than at Gramercy Park.

The common tasks of the canvassing boards of South Carolina and Florida and of the returning board, as it was known in Louisiana, were to investigate the accumulating allegations of violence, fraud, or other irregularities in local voting on November 7, to eliminate irregular ballots, and ultimately to certify the official count of the legally cast popular vote. Whichever candidate a board decided had received the greatest number of popular votes in a given state was entitled by law to that state’s entire electoral vote.

By now, as late returns were received and tabulated, both press and Democratic party spokesmen were claiming

The situations that came before the canvassing boards for investigation and decision followed a distinct pattern. The Republicans, finding themselves widely in control of local voting machinery in the South on election day, could practice the time-honored techniques of fraud: stuffing the ballot boxes, sometimes to the point where the number of votes cast exceeded the local population; throwing out Democratic votes; and making things as easy as possible for Republican “repeaters.” As for the Democrats, their favorite weapons were violence and intimidation. Their chief object of attack in 1876, as it always had been since the Civil War, was the Negro voter, whose affinities were predominantly Republican. The Democrats, organized as rifle clubs and night riders, sometimes employed the most barbarous extremes imaginable. Most of their outrages, however, did not take the form of mayhem. Economic and social pressures were the more standard practice. Unco-operative Negro renters were threatened with eviction. Negro field hands who professed Republican politics tended to become unemployed.

The canvassing boards were swamped not only with the facts of actual outrages and irregularities, but with hearsay, gossip, and the patently fabricated stories of witnesses carefully coached by unscrupulous Democratic and Republican partisans. Given the difficult task of the boards to sift the true from the false, and the enormous implications of their decisions, service on them would seem to have been a duty only for citizens of the highest competence and probity. In point of fact, unfortunately, the canvassing boards were by and large composed of the least admirable elements of the body politic. Investigating a Louisiana election just one year before the electoral crisis of 1876, James A. Garfield, Republican leader of the House of Representatives, summarily declared that the state returning board was a “graceless set of scamps.”

As events unfolded in 1876, the Louisiana board fully measured up to its infamous reputation. The mere fact that it was Republican in make-up did not mean that its decisions would automatically go Republican. The board, through its president, made abundantly clear that its decision was for sale. There is strong evidence that it offered to certify, in consideration of $1,000,000, that the Louisiana popular vote had gone Democratic. The deal, which was offered to the Democratic National Committee, was promptly rejected. In South Carolina and

But the big Democratic money never materialized, and the boards in all three southern states settled down to the hard business of finding ways to award the popular vote to Hayes. To reach the desired conclusions in Florida and Louisiana required the most arbitrary and callous indifference to elementary fair play. Florida, as several careful historians have pointed out, was “naturally Democratic.” It was the only one of the three disputed states where the majority of the population was white. This necessitated the most strenuous hocus-pocus on the part of the state canvassing board, but the board was equal to it. Never deterred by the weight of the evidence, no matter how overwhelming, the board consistently and ruthlessly used its discretionary powers in favor of the Republicans. In Archer Precinct No. 2 of Alachua County, for example, when unrefuted proof was offered that 219 names had been fraudulently added to the polling list and the same number added to the Republican majority, the total vote was allowed to stand. Cambellton and Friendship Church precincts in Jackson County ran up enormous majorities for the Democrats; the board coped with this formidable threat by throwing out the entire vote of the county on the meagerest of technicalities. In Louisiana, justice was also pitilessly mangled.

The more sensitive Republicans were repelled by the cumulative foul play. General Barlow openly voiced his disgust and his conviction that under a fair count Florida would have gone for Tilden by a small majority. Murat Halstead, eminent midwestern editor, leading Republican, and close friend of Rutherford B. Hayes, confided to the Governor that many of their party brethren were “staggered at the idea of taking the Presidency by throwing out 13,000 votes in Louisiana.” But Mr. Hayes was not among the staggered. “I have no doubt,” he wrote to Carl Schurz, of the result declared in Louisiana, “that we are justly and legally entitled to the Presidency.” If Hayes was consumed with any sentiment, it was that of enduring gratitude: when he became President the members of the several canvassing boards and their families were rewarded or, as the New York Sun put it rather more strongly, “debauched,” with good Administration jobs.

The next stage in the drama of 1876 entailed the disposal of the electoral vote. On the basis of the canvassing board findings, the Republican electors were declared elected in all three states, and in December they assembled in their respective state capitals and cast their votes for Hayes. The Democratic electors gathered independently, voted for Tilden, and also forwarded the results to Washington. From Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina, accordingly, the president of the Senate had on his hands two sets of conflicting electoral votes.

It was in the climactic hours

Meanwhile, in Oregon, the Democratic hopes, so badly crushed by events in the South, were suddenly uplifted by a totally unexpected development. Although the state had gone for Hayes by a narrow margin, it was discovered that a Republican elector, John W. Watts, was employed as a fourth-class postmaster at an annual salary of $268. The office, the Democrats were quick to argue, was one of “trust” and “profit” prohibited to presidential electors by Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution.

Oregon’s Democratic Governor, L. F. Grover, with the enthusiastic encouragement of his fellow partisans, state and national, ruled that Watts was ineligible and replaced him with a Democratic elector, E. A. Cronin. Actually, Grover was acting without legal authority. The existing state electors act provided that the remaining electors, and not the governor, fill any vacancy in the college. However questionable his appointment, Mr. Cronin’s constituted the one electoral vote Samuel J. Tilden needed to win the Presidency, for if Watts’ Republican vote had been thrown out and Cronin’s Democratic one substituted, the count would have been reversed, and even if Hayes had been awarded the twenty votes in the South, the final result would have been the election of Tilden, 185 to 184.

On the day the Oregon electoral college was scheduled to meet, Cronin and the three Republican electors assembled in a room set aside for their use in the state capitol. The secretary of state arrived with the electoral certificates and handed them to Cronin. The Republican electors asked for their certificates, but Cronin refused to surrender them. Thereupon, the Republican electors organized their own college, and Cronin, retiring to a remote corner of the room, turned himself into a one-man electoral college. His first action in his new corporate status was to declare that two vacancies existed; these he filled at once, naming J. N. T. Miller, who was waiting outside, and a Mr. Parker, who soon arrived. Both, needless to say, were Democrats, but just to make things look good, since only one vote was necessary to tilt the scale for Tilden, the rump electoral college gave one vote to Tilden and the other two to Hayes. The three Republican electors, holding their ground

The central issue emerging from the welter of frantic measures was stark and simple. Who would choose between the conflicting returns submitted by the rival electoral colleges of South Carolina, Florida, Louisiana, and Oregon? Who, in a word, would decide the momentous question: Was Hayes or Tilden to be the next President of the United States?

The Constitution provides that the electoral vote shall be counted by the president of the Senate (who in 1876, along with the majority of that house, was a Republican); it provides further that if no candidate secures a majority of the vote, the House of Representatives (then controlled by Democrats) shall select a President. It was to Congress, therefore, that the attention of the nation now turned, with the Republicans aggressively maneuvering to have the election dispute decided in the Senate, and the Democrats with equal ardor championing the House as the final forum.

No one was especially surprised when Rutherford B. Hayes and most Republicans in Congress began to contend quite vehemently that Article II, Section I of the Constitution provided the answer to the all-important question in these words: “The President of the Senate shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates, and the votes shall then be counted.” Hayes and like-minded Republicans read this language to mean that the president of the Senate, their fellow party member, Senator Ferry, should determine which of the conflicting electoral votes would be counted.

Tilden personally led the counterattack by compiling a learned History of Presidential Counts, and having a complimentary copy distributed to each member of the Congress. He succeeded in establishing that on no occasion had a Senate president exercised any discretionary power in counting the electoral votes.

In their own quest for a positive legal formula to solve the crisis, the Democrats turned naturally to the House of Representatives. Their chief contention was also based upon language in Article II, Section I of the Constitution, which provides that if none of the presidential candidates should secure a majority of the electoral votes, “then the House of Representatives shall immediately choose by ballot one of them for President.” But Senate Republicans argued that this language became operative only if both houses of Congress certified that the special situation contemplated existed; this the Senate was not disposed to do.

With party lines drawn firm, the houses of Congress became locked in a forensic standoff. From the massive effort of heated

While the congressional debate churned on inconclusively through the winter months, developments of a more ominous sort were taking place elsewhere in the country. Their common ingredient was the threat of civil war. The northern press was working overtime. “Tilden or war!” was its constant cry. The Albany Argus saw the grim “prospect of war in every street and on every highway of the land” if Tilden should be denied the Presidency.

The Democrats were by no means confining themselves to flaming oratory. They were actively girding for a contest of force. From every corner of the land, battalion commanders of state militias wrote to Tilden, placing their soldiery at his call. A reliable but distraught friend reported to Hayes that the Democrats were secretly organizing into military companies and inventorying every gun and bullet they could lay hands on, to be ready to spring to Tilden’s rescue.

Violent thoughts were by no means the monopoly of the Democrats. Certain Republicans—none, however, in official positions—were also threatening war. The chairman of the Iowa Republicans reported that 100,000 men were ready to back Hayes to the hilt if the Senate declared him elected. Amid all the stress and uncertainty, President Grant, viewing solemnly his responsibility for preserving the nation’s peace and safety, was not idle. Troops with light artillery were concentrated near Washington. The commander of the Army’s Eastern Department, who was suspected of harboring Democratic sympathies, was transferred elsewhere and replaced by a general in whom the Administration had absolute confidence. Internal Revenue agents were instructed to report any local happenings bearing upon the critical situation. But the Grant Administration’s several measures, it must be confessed, were by no means regarded with universal approbation. Various Democrats and not a few Republicans were fearful that Grant was merely using the crisis as a pretext to prolong his presidential term and establish himself as dictator, a kind of American Cromwell. A band of Democratic congressmen led by Fernando Wood of New York sought to impeach Grant “for misuse of the army and other offenses.” He replied that if the impeachment venture made headway in the House of Representatives, he would clap the Democratic ringleaders—all northerners—into Fort Monroe. A favorite story of the day told of two generals, both ex-Confederates, meeting in the middle of the electoral crisis and laughing joyously at the prospect of “marching into Boston at the head of the Union brigade.”

Happily, despite the menacing talk and gestures, there were also powerful forces for peace abroad in the land. The business community, mindful of the havoc of the late rebellion, was solidly opposed to war. “The Democratic business men of the country,” wrote James A. Garfield to Hayes, “are more anxious for quiet than for Tilden.” Southern Democratic congressmen had had their fill of war. In

For nearly one month, commencing in late December, peace-minded Republicans and Democrats struggled with all the parliamentary tools at their command to create and put into quick operation the machinery of compromise. Resolutions were drafted, committees appointed, caucuses held. From what was almost a miracle of swiftly achieved consensus, there sprang a law which one eminent constitutional authority, Edward S. Corwin, has called “the most extraordinary measure in American legislative history.” The act of January 29, 1877, created an Electoral Commission to solve the central issues of the crisis. The commission, as finally established, consisted of fifteen members, five from the House of Representatives, five from the Senate, and five from the Supreme Court. By interparty agreement, seven Democrats and seven Republicans were to be represented among the legislators and justices appointed to the commission; it was generally expected that as the fifteenth and, most likely, the deciding member, the presumably impartial Justice David Davis of Illinois would be chosen. The principal mandate of the commission was to decide the allocation of any disputed electoral votes; its decisions would stand unless reversed by both houses of Congress, which was quite unlikely in light of the fact that neither party controlled both.

The commission plan, be it noted, evoked no spoken praise or private admiration on the part of the two presidential candidates. At every stage, from conception to final form, the plan was sourly regarded, both at Columbus and at Gramercy Park, as “surrender.” In the end, however, both candidates regretfully accepted it as a fait accompli.

For all of Tilden’s pessimism, the Electoral Commission scheme was generally regarded as a Democratic victory. It was believed that Justice Davis, although officially regarded as more or less impartial, would side with Tilden and tip the scales of decision.

Whatever joyful expectations the Democrats were harboring were suddenly dashed by a wholly unimaginable disaster. By the day the Electoral Commission bill went to the President for signature, news arrived from Illinois that the Democratic majority of the state legislature had just elected David Davis to the United States Senate. Davis lost no time in declining the proffered appointment to the Electoral Commission.

In his place Justice Joseph

With the commission now constituted, Congress was ready to proceed with the counting of the electoral votes. On February 1, senators and representatives gathered in the House chamber at 1 P.M. with the galleries full and privileged visitors crowding the floor. After tellers representing each house were appointed, the president of the Senate turned to a wooden box, a little more than a foot on each side, selected the return of Alabama, and the count began. All went swimmingly until Florida was reached and her two conflicting returns read. Each side made its objections and all the papers involved were turned over to the Electoral Commission.

Two batteries of able lawyers, personally selected by Hayes and Tilden, presented their opposing arguments to the commission. The Republicans contended that the language of the Constitution limited Congress to the ministerial act of counting the electoral votes presented by the officially established state authorities. The Democrats pleaded that Congress, or its agent, the commission, had the duty to inquire into the circumstances surrounding the choice of electors in the disputed states. Such an inquiry, the Democrats contended, would uncover gross irregularities that would compel the award of the electoral vote of the three states to Tilden. After hearing argument, the commission spent a full day in camera, pondering the disposition of the Florida case. Washington and the country were strangulating with excitement and suspense. Justice Bradley’s vote was generally expected to hold the balance.

On the night before the decision was due, Hewitt, who was on the brink of nervous exhaustion, again dispatched his good friend Stevens to Bradley’s house. The Justice graciously read the opinion he intended to hand down the next day. To Stevens’ great joy, which he struggled to keep within discreet bounds, the opinion upheld the Democratic position and thus, by adding Florida’s three electoral votes to his uncontested total of 184, ensured Tilden’s election with two votes to spare. Stevens returned to Hewitt with the tremendous news at about midnight. Next morning, however, the two were dumbfounded when Bradley did a complete about-face and presented a decision upholding the Republicans. Sometime between midnight and sunrise, Bradley had changed his mind, apparently under the influence of the Republican senator Frederick T. Frelinghuysen of New Jersey and Secretary of the Navy George M. Robeson, who had arrived after Stevens had departed. They seem to have been strongly aided by the dominating Mrs. Bradley. The tenor of the trio’s argument was that whatever the strict legal equities of the situation, it would be a national disaster if the government fell into

The commission swept on inexorably, handing down decisions on Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina consistently favorable to the Republicans. Its final tally gave the electoral vote to Hayes, 185 to 184. Editor Reid’s hopes had come true. Significantly, just after Florida and Louisiana had been decided, and before Oregon and South Carolina were reached, Rutherford Hayes was writing confidently in his diary, “The inaugural and Cabinet-making are now in order.”

Shortly after the Oregon decision in late February, however, a group of Democrats, enraged by the disastrous turn of affairs in the Electoral Commission, proposed as a last-ditch measure to delay the completion of the electoral count. March 4, the day the Constitution then required a presidential term to begin, was only days away. If no President were declared elected by that time, an interregnum would occur, opening up infinite possibilities of mischief. Neither the Constitution, precedent, nor statute made any provision for such a contingency.∗ Anything could happen, even war itself. If, for example, Ulysses S. Grant continued in office, which from duty or ambition he might feel driven to do, he could be challenged and defied as an outright usurper. The chief instrument to be relied upon by those bent upon disrupting the machinery of government was the filibuster. Every necessary ingredient was present. The time was perfect. A few days’ delay and the damage would be done. In the House of Representatives Democratic manpower was more than adequate to carry it on.

Only some desperate eleventh-hour negotiations between the representatives of Governor Hayes and the southerners saved the country from the filibuster and the dreaded interregnum. The negotiations, occupying nearly two days and nights and conducted principally at the Wormley Hotel in Washington, produced what became known as “The Bargain,” a complex of pledges by the Hayes representatives of major measures for southern home rule, paramount among them a promise to withdraw federal troops. The southerners unhesitatingly agreed, as quid pro quo, to withdraw from the projected filibuster.

Although the bulk of the southerners were now lost, the possibility of a filibuster was far from dead. A goodly number of northern and western Democrats were fully resolved to carry it on, and Hewitt and Speaker of the House Samuel J. Randall, responsible men acutely mindful of the implications of the situation, begged Tilden to put an end to the nonsense with a decisive statement. Tilden dillydallied. Only after some long hours of introspection at Gramercy Park did he conclude that the situation presented an absolute choice between accepting the Electoral Commission’s results or facing civil war. Accordingly, he wired Speaker Randall that the verdict of the Electoral Commission must be accepted. All except a few die-hard Democrats respected Tilden’s wishes. The recalcitrants made a final but vain outburst when the count of Wisconsin was reached in the early morning of Friday, March 2. The high point of the acrimonious discussion was the observation by Democratic Congressman

Without exception, the principal historians of the period—James Ford Rhodes, James Schouler, William A. Dunning—all concluded that Tilden was robbed of Louisiana and probably of Florida. President Grant confided to Hewitt his belief that Louisiana, and therefore the Presidency, belonged to Tilden. Such estimable Republicans as Roscoe Conkling, E. L. Godkin, and Samuel Bowles all were convinced and publicly asserted that Tilden had been elected. On the basis of the popular vote, a majority of the people held an identical opinion. However creditably Hayes went on to perform as President, his Administration always labored under a clouded title.

A principal item of his program was electoral reform, a step fully augured by a diary entry the future President made on January 26, 1877, amid the tensions of the awaited decision. “Before another Presidential election,” Hayes wrote at the time, “this whole subject of the Presidential election ought to be thoroughly considered, and a radical change made.... Something ought to be done immediately.” But nothing was done immediately, and certainly no “radical” change has been effected since Hayes’s day.

It was not for a full decade after the 1876 election that Congress enacted a law empowering each state to determine the authenticity of its selection of electors. It was not until the late date of 1933 that the Constitution directly provided for the nightmarish possibility —which loomed so starkly in the Hayes-Tilden controversy—that the incumbent President’s term might expire before the next President or Vice President could be chosen. The Twentieth Amendment, adopted that year, specifies that Congress may in such a case declare “who shall act as President, or the manner in which one who is to act shall be selected, and such a person shall act accordingly until a President or Vice-Président shall have qualified.”

But no amendment or statute has yet solved the central problems which bedeviled the election of 1876. Irregularities in the selection of electors can still occur in the states. The Negro voter can still be intimidated and defrauded of his right to vote. A “minority President” like Hayes, who receives a majority of the electoral vote but not of the popular vote, can still be elected. These disquieting possibilities, which were at the bottom

Our presidential election system remains a hodgepodge of divided responsibilities between state and nation. The electoral college lingers on, normally a meaningless anachronism, but potentially, as in 1876, a creator of infinite mischief.

*It was true that the Twelfth Amendment, adopted in 1804, made it clear that if a Vice President had been chosen—wither by the electoral college or the Senate—to take office on March 4, 1877, he would have acted as President. But the two vice-presidential candidates of 1876, Republican William A. Wheeler of New York and Democrat Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana, wre tied up in the same electoral-vote as Hayes and Tilden.