Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February 1960 | Volume 11, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February 1960 | Volume 11, Issue 2

Some years after the Revolutionary War, Henry Knox, one-time major general and chief of artillery in the Continental Army, rose before the Massachusetts legislature to speak on a bill in behalf of his former comrades in arms, the Marblehead fishermen. Standing there, his hulking 280-pound frame commanding every eye, Knox recalled the cold Christmas night in 1776 when these brave men had ferried Washington’s army across an ice-jammed river to launch the attack against Trenton.

In a booming voice that filled the hall, Knox recounted that memorable episode. “I wish the members of this body … had stood on the banks of the Delaware … in that bitter night … and seen the men of Marblehead, and Marblehead alone, stand forward to lead the army along the perilous path to … Trenton. There, Sir, went the fishermen of Marblehead, alike at home upon land or water … ardent, patriotic, and unflinching whenever they unfurled the Hag of the country.”

Such was the caliber of John Glover’s regiment, one of the most unusual units in the whole Continental Army. It was composed almost entirely of seafaring men from Marblehead, soldier-sailors who could march onto a battlefield or tread a ship’s deck with equal ease. Able to handle oars as well as muskets, they were ordered to man small ships and boats for the Army so often that they have gone down in history as the “amphibious regiment.”

Everything about the regiment smacked of the sea. Many of the men marched oft to war in the same blue jackets, white caps, and tarred trousers they wore off the Grand Banks. Even the famous discipline of the unit was the result of their occupational training. Unquestioning obedience to the captain was the rule of the sea; the officers of Glover’s regiment made it the ride of the land as well. One Pennsylvania officer who ordinarily took a dim view of New England troops was forced to admit that this outfit was different: “There was an appearance of discipline in this corps … it … gave a confidence that myriads of its meek and lowly brethren were incompetent to inspire.”

Most Marbleheaders were foes of England because of the Fisheries Act, passed in the spring of 1775, which threatened to deprive them of their livelihood by barring them from North Atlantic fishing grounds. Out of this hatred a provisional regiment of minutemen was born in Marblehead three months before the rattle of musket fire was heard at Lexington and Concord. Indeed, Marbleheaders came close to filling the niche in history held by Lexington minutemen. On February 26, 1775, a British regiment under Colonel Thomas Leslie landed off Marblehead Neck, headed toward Salem and a hidden store of patriot arms and ammunition. It was a mission exactly like the Concord mid that precipitated war two mouths later.

The entire Marblehead regiment turned out, and although they were too late to halt the British, they took up positions along the road to give Leslie’s troops a hot reception upon their return. But Salem patriots removed the military supplies out of reach of the British, and after a clergyman intervened to prevent bloodshed, Leslie agreed not to press his demands that they be surrendered, instead of firing upon the redcoats as they returned empty-handed to their transports, the Marbleheaders formed an escort behind Leslie’s men and marched in mocking cadence to the British music.

Like most units of Massachusetts minutemen, the regiment underwent a series of reorganizations after war broke out, but two factors made for continuity. Most of the men still hailed from Marblehead, and from the spring of 1775 through the winter of 1776, the regiment was under the same commander.

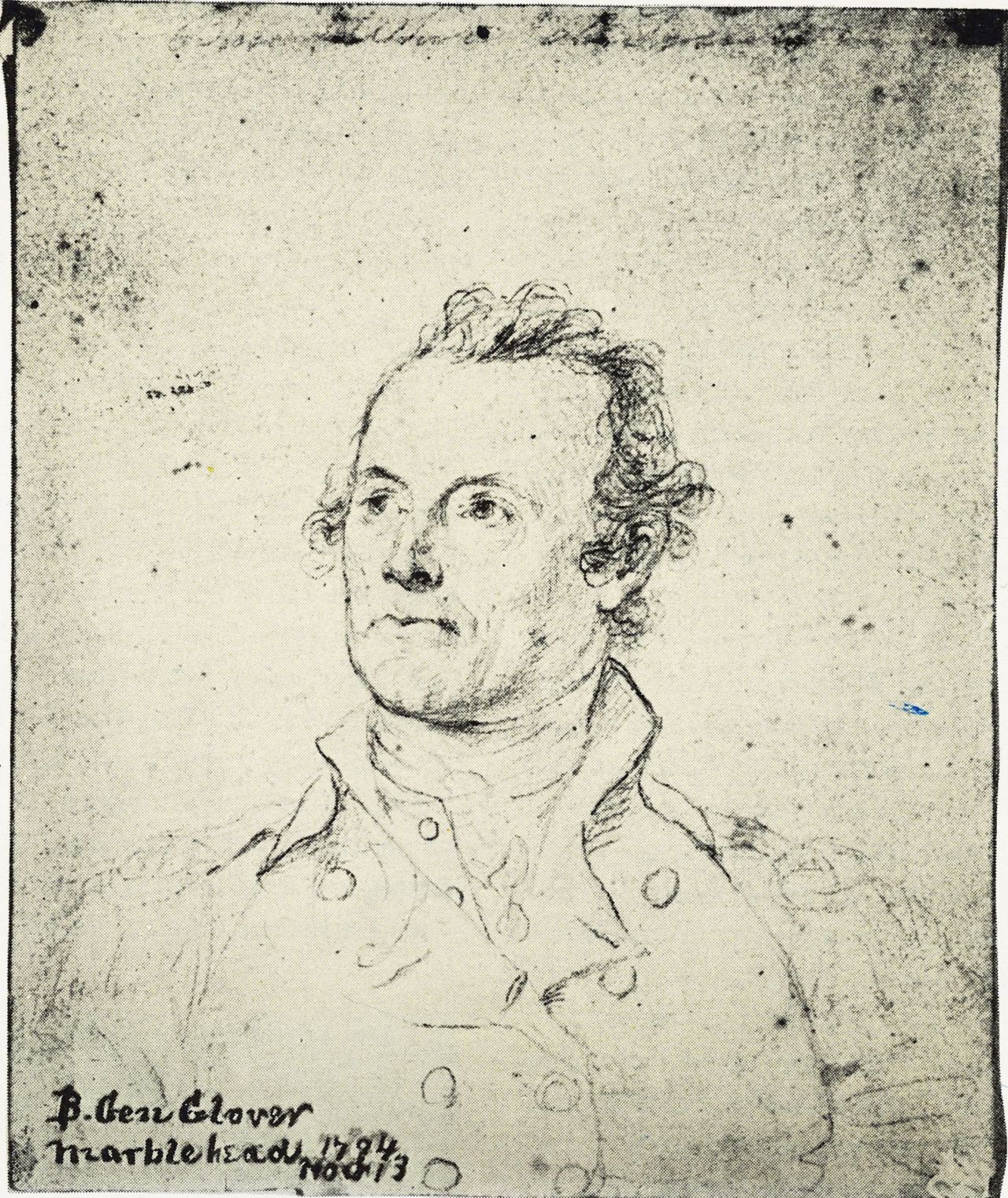

Colonel John Glover, the scrappy little man who led the outfit, was born the son of a housewright in nearby Salem and spent his early childhood there be fore moving to Marblehead. He was forty-three, the same age as George Washington, when war broke out. His handsome, finely chiseled features, sketched late in life by Colonel John Trumbull, show a broad, high forehead, clear, well-set eyes, and a long, broad nose. The outthrust jaw gives some hint of his toughness and determination. Although he was very short, Glover more than made up for his lack of height by his boundless energy.

Glover’s prewar career consisted of “shoes, ships and sealing wax.” He made his start as a simple cordwainer—a fact that prompted some wag to remark that he gave up his awl for his country when he entered the Army—but in fact Glover stayed at the shoemaker’s bench only long enough to earn a stake for a second career as a shipowner and merchant. In the lyGo’s at least three Glover vessels sailed to the Iberian Peninsula, the West Indies, and other colonies in America, inevitably he was drawn into the major Marblehead industry — the fisheries. This third business venture proved to be his most profitable. Shrewd, thrifty, and hard-working, he accumulated a tidy little fortune before the war began.

Although he had seen no combat, Glover was not a complete novice at the art of war. Behind him were considerable training and experience as an officer in the local militia. Appointed as an ensign in 1759, he advanced rapidly to captain lieutenant in 1762 and was made captain of a company in 1773. it is even probable that he received some schooling in military theory. Family tradition