Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1960 | Volume 12, Issue 1

Authors: Fred L. Engelman

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1960 | Volume 12, Issue 1

It was St. John’s Day, a gentle introduction to summer, and the road, Lowered by leafing elms and poplars and oaks, carved through lush grain fields and meticulous flower gardens. The two reluctant traveling companions had set out from Antwerp at nine that morning. For more than an hour they had been delayed at the River Scheldt, a crowded anchorage for British men-of-war, while petty officials bickered over their tolls, but by early afternoon they were hallway to Ghent, the old Flemish capital, where they were to seek peace with the British.

The older, squatter “Minister Plenipotentiary and Extraordinary of the United States” was John Ouincy Adams—minister to Russia, son of his nation’s second President, and a righteous pedant who was humorless to the point of exasperation. The younger commissioner possessed more humor but infinitely less virtue. He was Jonathan Russell, United States minister to Sweden, and he barely had been able to present his credentials in Stockholm before departing on the three-week journey. For Adams the trip was an unexpected delight, and now that he was back among the scenes of his early manhood he was moved almost to tears. At four o’clock on this June 24, 1814, their carriage came to a halt in Ghent’s Place d’Armes before the Hotel des Pays-Bas. Adams was gratified to find that they were the first commissioners to arrive.

In less than two weeks, three other United States ministers joined them. Three days after Adams and Russell had established themselves came James Asheton Bayard, a patrician senator from Delaware and the only Federalist on the commission. He was homesick and in chronic ill health, and he was provincially unable to accept European customs. In little more than a year he would die, just six days after reaching his home in Wilmington.

The day after Bayard’s arrival brought rain; it also brought Henry Clay, wearied by an “excessively unpleasant” trip from Gothcnburg, Sweden. Not yet the Henry Clay who engineered great sectional compromises and aspired endlessly to the Presidency, this lanky, carelessly dressed, lean-laced, bushy-haired young man of thirty-seven had been a United States senator from Kentucky, nnd a former Speaker of the House. He championed the interests of the trans-Appalachian West with the devotion of a guardian who well understands the potential of his ward. A prime instigator of the War of 1812, he was now in Ghent to aid in ellecting a happy conclusion to this great crusade, which had an unfortunate tendency to resemble comic opera, deadly and expensive though it was.

For as Clay sought the warmth and dryness of the Hotel des Pays-Bas, British troop transports nosed toward the mouth of the St. Lawrence. Their burden, four brigades strong, would, in little more than two months,

But to Clay, as he watched the shadows of evening reflected in the puddles of the Place d’Armes, British military intentions were but a suspicion. It was enough to question British intentions for peace and to wait impatiently for the coming of their commissioners.

John Quincy Adams, the first man named to the American commission and consequently its titular head, had already instituted regular seminars for his charges when Albert Gallatin, the most astute member of the group, arrived from Paris. This scion of wealthy Swiss gentry had established and celebrated his maturity by emigrating to the American colonies, then in revolt against England. Continental manners and speech notwithstanding, he gained recognition in the bear pit of western Pennsylvania politics and soon rose to national eminence, serving for twelve years as Secretary of the Treasury under Jefferson and Madison. He was probably the most illustrious and dependable servant of the often-feeble Madison administration and, fortunately for his adopted country, he was to exert his tact, patience, humor, and brilliance throughout the trying months in Ghent.

Partly from inclination, but mostly because of British evasion, Gallatin and the other American commissioners had been meandering through northern Europe, like so many disgruntled and separated patrons of a misguided tour. More than a year before, Gallatin and Bayard had sailed from New Castle, Delaware, for St. Petersburg, Russia. There they intended, with Adams’ assistance, to treat with England under the benevolent mediation of Czar Alexander I. They arrived in St. Petersburg only to discover that Lord Liverpool’s government, on the grounds that the war was an internal affair, had rejected the Czar’s thoughtful but meddlesome overture, and that the Czar himself was somewhere in the wake of Napoleon’s retreat across Europe. Gallatin and Bayard spent six dreary and confining months in the frigid Russian capital before pushing on through Berlin and Amsterdam for London.

B ut before arriving there, Gallatin and Bayard received confirmation that President Madison had accepted the British proposal for direct negotiations in Gothenburg, Sweden, and that Henry Clay and Jonathan Russell were sailing from New York to join the original commission of three. Clay and Russell had scarcely unpacked their bags in Sweden—and Adams, a dour and self-pursuing Elixa, was still battling Baltic ice floes—when Gallatin and Bayard assented to, and to some extent encouraged, a British proposal to make Ghent, not Gothenburg, the scene of their discussions. Ghent was a mere Channel crossing from London, and Gallatin and Bayard hoped that this proximity would enable the British commission to act with greater dispatch.

By July 6, 1814, the entire American mission was assembled. They were to wait a month for their British counterparts to arrive, and this added delay did little to invigorate their

Not until late evening of the first Saturday in August did the British mission arrive in Ghent. Two days later, after fifteen months of fruitless inquiries and travel, the Americans for the first time met their adversaries—Lord Gambier, a churchgoing, armchair admiral who was approaching senescence; Henry Goulbtirn, the thirty-year-old Under Secretary for War and the Colonies, who in lime was to be Chancellor of the Exchequer; and Br. William Adams, an obscure Admiralty lawyer who was destined to justify his obscurity.

It was symptomatic oi London’s attitude toward the United States that the government had briefly considcred naming Lord Bathurst, Colonial Secretary, head of the commission to Ghent but decided that the settlement of this contemptible uprising did not rate a ranking cabinet minister. They sent instead a commission whose members were unknown even to the populace of Great Britain and at its head placed a man who had gained his peerage for participating, on one of his infrequent seagoing excursions, in the bombardment of defenseless Copenhagen. At Ghent, Lord Gambier was never more than a polite, impressive-looking, usually silent figurehead. Dr. William Adams did his best to make up for Gambler’s taciturnity, but he was no Demosthenes, in his most uncontrollable moments he was a sputtering old fool who talked himself and the British cause into impossible corners. His family, he told the American Adams, was on the downgrade, and John Quincy, quite willing to agree, was much relieved to discover that they probably were not cousins.

Early in the afternoon on the eighth day of August, Lord Gambier, alter he and Adams had exchanged pious hopes for peace, turned the meeting over to Goulburn, who promptly rattled off the British terms. Il the Americans insisted, the British would discuss the impressment of American seamen—one of the major published reasons the United States had gone to war—but Goulburn suggested that this was about all they would do about the problem. The British would require some revisions along the Canadian boundary. They would not renew the privilege—written into the Treaty of Paris in 1783—that allowed the Americans

The Americans were stunned. Bayard called the terms those of a conqueror to the conquered. Posterity might raise questions, but in that summer of 1814 the government of Lord Liverpool saw no reason to doubt the wisdom or justice of its demands. For most of Henry Goulburn’s lifetime his nation had been locked in a sometimes lonely world struggle with France. The British could not countenance the claims and complaints of a semicolonial neutral when their fate was in the grasping hands of Napoleon. In 1812, he had already penetrated Russia when the English Cabinet received the bitter news that the Americans had treacherously declared war on them. For a year and a half the British were much too busy in Europe to worry about proper punishment for the transatlantic upstarts, but at Fontainebleau, in April of 1814, a forlorn ex-emperor of France waved farewell to his troops and commenced his humiliating journey to Elba. Now it was possible to deal with the would-be invaders of Canada, the distant cousins who brazenly embarrassed the world’s greatest naval power, those noisy colonials who kept insisting they were independent and equal. For the first time in twenty years, all Europe was at peace, and the British lion roared in triumph. “There is no public feeling in the country stronger than that of indignation against the Americans,” said the London Times of April 15, and on English and continental docksides ominous lines of Wellington’s seasoned veterans, the potent symbols of this indignation, waited to board their America-bound transports.

T he five highly independent Americans who composed the uneasy family of “Bachelors’ Hall” on the Rue des Champs were stung but not altogether taken unaware by the severity of the British demands. Yet even the shrewd and usually imperturbable Gallatin was upset by the apparent evidence that the British government was entranced by its own propaganda. He had anticipated lip service to popular demands, but Lords Liverpool, Castlereagh, and Bathurst, the real English negotiators, seemed to be in earnest. And Gallatin’s discomfiture increased when he considered the now seemingly absurd terms so fervently expressed in the instructions to the American commission.

A sorely tried, peaceable James Madison had signed the declaration of war

Not all their aspirations, though, had been maritime. The largely Federalist coastal states, willing for the sake of profit to suffer restrictions on their commerce and to swallow insults to national pride, were almost unanimously opposed to an open rupture with Great Britain. It was this attitude that lay behind New England’s refusal to co-operate in the war. The narrow margin of votes in favor of war came from the West and the South, states that for the most part had neither ships to sail nor oceans to sail upon. One had to be deaf to miss the westerners in Congress, Henry Clay very notable among them, who clearly spelled out the West’s reason for going to war: greedy appreciation of Canadian real estate. The motto of the day became “On to Canada!” and the march had begun even before the care-worn James Madison could put his pen to the war document. Sadly, however, the invasion of Canada became a sort of Gilbert and Sullivan fiasco, and as Adams and his colleagues faced their adversaries at Ghent in the summer of 1814, the military initiative had passed to the British. Yet hope lingered painfully in the battered American breast: the hunger for Canada and the sincere but impracticable desire for a guarantee of the rights of neutrals.

The delay in the start of the negotiations, and the great time lag in communications, made most of the instructions to the American peace mission irrelevant by the time the commissioners received them. The basis for a sizable portion of the American neutral rights objective was removed less than a week after the American declaration of war, when Lord Liverpool’s government revoked the Orders in Council—its legal justification for interference with American ships on the high seas. This left impressment the sole ostensible reason for prosecuting the war, for only incompetent generals and uninhibited politicians could publicly avow American designs on Canada.

In some of his instructions (which, for good reason, were never published) James Monroe, Secretary of State and sometime gratuitous adviser to the War Department, did go so far as to include the desirability of the cession of Canada. He suffered from the delusion that Canada, like an overripe fruit, would drop into the American basket anyway; so England might as well face facts and get it over with. Monroe also wrote to his ministers of the necessity for getting some meaningful definition of a blockade and of neutral rights in general. In addition, he covered other, less significant points, but the bulk of his prose was lavished

For assurances that this evil alone would cease, the American commissioners were authorized to sign a peace treaty, but if they failed on this point “all further negotiations will cease, and you will return home without delay.”

With the end of hostilities in Europe, the British no longer found it necessary to recruit their Navy by wholesale kidnapping, but they would sooner have given London to the Turks than surrender their “right” to impressment. The Americans in Ghent were keenly aware of this. None of them seriously nourished the hope that the British could be convinced of the pernicious and unlawful effects of impressment, and Gallatin had written as much to Monroe several times over. But as a hot August sun warmed the Flemish canals, the abolition of impressment was still the primary goal the five Americans were expected to achieve. Regarding the proposed cession of Canada as patently insupportable, they had quietly put it to rest before the peace talks began, although Adams, in a moment of madness, would later try but fail to revive the subject.

Jonathan Russell, the weakest link in the American peace chain, was off visiting Dunkirk at the time his colleagues were absorbing the harsh British terms of the first conference on August 8. That evening after dinner, Adams, Bayard, Clay, and Gallatin were discussing their brief for the morrow when a messenger arrived from Paris with more recent instructions from Monroe. By one o’clock the next morning they had deciphered the code and were able to read, much to their relief, “you may omit any stipulation on the subject of impressment, if found indispensably necessary …” The four men needed little more to convince them of the indispensable necessity. One of the principal causes of the war was now an all-but-forgotten resolution, and Adams had a rather trivial case to present to the British later that day.

He carefully explained to them that he and his colleagues were not instructed on Indians or fisheries, but that they would like to reach some definition of the respective rights of neutrals and belligerents, and that they intended to put forward claims of indemnity for British seizure of United States shipping before and during the first six months of the war. These American terms, however, were dwarfed by the enormity of the British ultimatum.

Actually, it made scant difference what case the Americans presented. The triumphant British held the initiative, and far from pressing for Canada, the American commissioners would need all their wits to preserve the United States.

Wit, skill, and determination they had. However dissonant their private councils might be, they wrote firm, trenchant notes, the propaganda value of which was to influence the British government in a way it did not anticipate. In conference they were admirable courtroom lawyers who bettered the third-rate British commission at almost every step. To the horror of their superiors in London, the three Englishmen virtually admitted that the

Whatever the personal advantages the American commission held over their immediate adversaries, however, there was no escaping the fact that the British government held the high military cards. Their crack European veterans were already ravaging the American coast, and Sir George Prévost was coming down the western shore of Lake Champlain at the head of an imposing army that was to be used, in the words of a British colonel, “to give Jonathan a good drubbing.” The British in Ghent happily informed their American opposites of British doings across the Atlantic, and a successful peace seemed hopelessly elusive when on August si, after several inconclusive British-American meetings, John Adams sat down at his desk to draft the first written American answer to all the British demands so far. His despair was not lifted when his companions examined his efforts. Gallatin thought some of his expressions were “offensive”; Clay was sarcastic about his “figurative” eighteenth-century language; Russell, who had returned from Dunkirk, set about improving John Quincy’s grammar; and Bayard thought everything should be stated somewhat differently. For four days they dismembered each other’s offerings, and at 11 P.M. on August 24 they had combined the remnants into a note that none of them really liked. It would, Adams predicted, “bring the negotiation very shortly to a close.”

When they broke up their meeting to retire it was still early evening in Washington. The five Americans in Ghent had no way of knowing that Dolley Madison would spend the night in a tent; that her husband, leader of the American people, would ignominiously ride through most of the darkness along a Virginia road choked with refugees; that when dawn came to Washington, the Capitol, symbol of American majesty and dreams, would be hardly more than smoldering ruins at the feet of the enemy.

Gallatin, Adams, and company were not to hear of the shame of Washington until October 1. But the negotiations did not come to an untimely end for the simple reason that the British did not want them to end. In early September there was another exchange of notes between the two commissions, and then for ten days there was silence while the Americans awaited the next British move. It was the morning of September 20 when the third British note was delivered to John Quincy Adams. The Americans answered it a week later and once again settled back impatiently to bide their time. They were at dinner when the fourth British note arrived on October 8; coming two months after the negotiations

The British had, in fact, been softening their diplomatic blows for a month, but the Americans were so accustomed to saying “no” with vehemence and frequency that their vision was blurred when they read prose that had originated in Whitehall, and they failed fully to perceive the changes. Even Goulburn and his companions were not certain of their government’s intentions.

The true spokesman of the British commission and the one who handled the correspondence with the ruling triumvirate of Prime Minister Liverpool, Foreign Minister Castlereagh, and Colonial Secretary Bathurst, was Henry Goulburn. He was an honest, devoted, undiplomatic diplomat who smarted from surplus zeal. He was convinced, not without reason, that his mission was to rub Yankee noses in the dirt. Not that he had anything against the American commissioners, but they would give in or Goulburn would send them packing. He heaped unwanted advice and mistaken notions on his superiors, and, to their chagrin, he gleefully wrote to them when he thought the Americans were about to go home. He ached to apply the coup de grâce . He was to ache unrelievedly.

To some extent, Goulburn and his companions can be forgiven for mistaking their government’s somewhat uncertain aims. Neglectfully, but sometimes intentionally, the British Cabinet largely failed to correct their messenger boys’ illusions. Both Liverpool and Castlereagh complained that the three lonely gentlemen had “taken an erroneous view of the line to be adopted,” but as late as September 16 Goulburn wrote a sarcastic letter to Bathurst, saying that he could not thank him enough “for so clearly explaining what are the views and objects of the government.”

In fact, the most important of these objects was delay. Lord Liverpool and his advisers were not altruistically devoted to the interests of the North American Indians, but they did mean to put up a geographical barrier between Canada and the obstreperous American filibusters; what they failed to accomplish by diplomacy they serenely expected to gain on the bloody field of glory—after which they could dictate a peace. You cannot skin a cat, however, once he has fled captivity, and Goulburn’s diligent reports that the Americans, despairing of any real progress, were about to go home finally caused concern in London.

In truth, the British government had been sorely vexed by the unyielding stand of the American commission. The nearly bankrupt American government was disintegrating under the dual pressures of English arms and New England’s tendencies toward disunion, and yet the men at Ghent would not budge. Furthermore, although the ordinary Englishman wanted to wallop the American, he would not much longer be disposed to pay for the pleasure.

And all was not well in Europe. The mad Bonaparte appeared to be safely tucked away on Elba, but Paris was chafing under the yoke of fat Louis, and Alexander of Russia was casting covetous glances toward Poland’s territory.

With pressures mounting, the British government slightly reduced its demands in its notes of September 4 and 19, but the notes were ambiguously worded, and after the British commissioners got through with them they were contradictory as well, in tenor if not in fact. London had sternly advised its representatives at Ghent to constrain their editing so that it did not alter intent, but neither they nor the Americans fully understood what the intent really was, and Goulburn did not mean to lose face even if his government did. To both notes, the Americans returned their usual exasperating retorts. These upset and infuriated the British Cabinet, but the annoyance of the transatlantic war itself was becoming politically unbearable and economically prohibitive. On October 1, Liverpool wrote to Castlereagh in Vienna of the Cabinet’s “anxious desire to put an end to the war. … I feel too strongly,” he continued, “the inconvenience of a continuance of the war not to make me desirous of concluding it at the expense of some popularity.” To accomplish this, the ultimatum with regard to the Indians was scaled down. The note delivered to the American dinner table just a week later no longer demanded an Indian state in the American backyard; it was simply necessary that peace with the Indians be part of the British-American peace treaty. The British also had omitted entirely any pretension of maintaining unilateral armaments on the shores and waters of the Great Lakes, a claim which they had already begun to soft-pedal in a previous note.

Thus the two insurmountable barriers to serious discussions had been removed. Of course the British Privy Council, with a bombastic assist from the eager Goulburn, could not refrain from stating their muchdiminished Indian ultimatum in abrupt and menacing tones: the Americans would accept this milder cathartic or negotiations would close. And, significantly, the note laid claim to a small helping of Maine. With confidence the British waited for the next mail pouch from their commanders in America; the news, they were sure, would justify making the peace treaty a real-estate deed—a touch of Maine, a bit of New York, an island, a fort, a port here and there.

The British note was delivered to a house whose occupants were getting on one another’s nerves. The confined living quarters and the frustrating pursuit of peace were taking their toll. None of the other American commissioners was long at ease with the querulous John Quincy. Bayard, who for six months had endured Adams’ company in Russia, thought the man “singularly cold and repulsive”; it is tragic when one reflects that Bayard was the closest thing to a friend Adams had in Ghent. And Clay, who by

By late September the three-storied house on the Rue des Champs resembled an isolated boarding school during winter term. Its occupants were tired of one another’s company, depressed by the plight of their country, and numb from British diplomatic attacks. They wrangled over trifles. For days they passionately disputed over which of their messengers and secretaries would carry which dispatch—and ended by not sending the dispatches at all. Gallatin and Bayard began to show signs of “despondency.” Momentarily they talked of complying with some of the terms in the British note of September 19, but Adams and Clay, acting in concert for a change, stiffened their resolution. It was well they did; for otherwise the British might never have had to give way in the note which now arrived on October 8.

The first American reaction to the note was circumspect but optimistic. For five days Adams and his companions drafted, edited, and debated their answer. Adams raged. He was violently opposed to accepting the Privy Council’s ultimatum on the Indians, softened though it was when stripped of its rhetoric. He wanted to match the “arrogance” of the fifteen-page British note word for word, insult for insult. He even exhumed Monroe’s instructions and decided that he and his colleagues should, after all, advise the British that it was to their own advantage to give up Canada. Gallatin and Clay tried to reason with him, but it was Bayard, being “perfectly friendly and confidential,” who calmed him down—by producing a bottle of Chambertin and dispensing solace and prudence along with the wine. Two days later, at noon on October 14, Adams joined the others in Clay’s room and grudgingly signed his name to their answer.

That answer spewed forth a torrent of words on the subject of Indians, but the British mandate on Indian pacification was accepted, however ungraciously. It was, said the American commissioners, similar to their own suggestions on the matter (suggestions which had been made, strangely enough, in September by the same John Quincy Adams who went livid when he saw the words in British handwriting). In conclusion, the Americans asked for

What the Lord did to British hearts will remain a celestial mystery. In any event, on October 17, while the British commissioners were considering their rejoinder, it was their turn to receive bad news from America. On September 11, Thomas Macdonough, working his ships as if they were water-borne carrousels, had outlasted a superior British naval force in Plattsburg Bay, and Sir George Prévost, who was to have severed New England from the not-so-United States, had sunk in spirit as his naval brothers were sinking in fact and promptly marched his intimidating horde back to Canada. A few days later, Robert Ross, the general who had put the torch to Washington, lay dying near unconquered Baltimore, listening to the same bomb bursts that provoked patriotic verse in Francis Scott Key.

The discouraging news did not, however, noticeably temper the next British note to the American commission. It insisted that the Americans accede to the principle of hold-what-you-have, specifying that a good part of Maine and some forts and islands should be given to Canada, and repeating the prohibition against the drying of fish on Canadian shores. On the matter of a treaty project, the British demurred. Their terms were clear, they said; it was up to the Americans to produce a plan. The American answer was prompt and negative, and it gave Lord Liverpool the queasy sensation of balancing on a seesaw that could not touch ground at either end. He wanted to break off the negotiations and fight, but he thought of the Czar, of Talleyrand, of the British budget, and wept. On the last day of October Anthony St. John Baker, secretary to the British mission at Ghent, trotted across town with a note that was brief, terse, and only too familiar. The British had given their terms. They had nothing more to say. They awaited the American project. They were, they neglected to say, stalling.

The American commissioners had in fact been discussing and composing a treaty project for two days when Baker surrendered his blunt message and a packet of London newspapers to four sober men, three of them the restless audience for an Adams monologue. Only Russell was missing; it was perhaps one of his greatest contributions to the progress of peace.

An occasional merchant, lawyer, and unlikely diplomat from Rhode Island, Jonathan Russell was a perverse and bristling mixture of acute self-adoration and gelatinous principle. Like a sulky little boy, he fumed when Gallatin forgot to tell him of a Ghent social invitation, and at the end of September he moved away from his condescending peers and back to the more appreciative companionship of the secretaries and messengers at the Hotel des Pays-Bas. Adams

Clay would have snickered had he known of Russell’s praise. Clay was the epitome of crude, calculating, dice-throwing western ambition, and in him lay the source of the overstatement of American attitudes at Ghent. The British, he maintained, were nothing more than card players, faking a flush when they held a pair of deuces. At a time when his companions floundered in a vale of pessimism and made sounds like departing tourists, Clay blandly asked the British for his passport and sent Goulburn’s spirits surging. But Clay was playing “brag.” He later asked Adams if he knew how to play. John Quincy most surely did not. It is, said Clay, the art of “holding your hand, with a solemn and confident phiz …” Adams, however, could not put on such a “phiz.”

When the British temporized and insisted on an American draft of a treaty, the United States commission was not surprised, but after months of total, unstinting defense they were flustered by the necessity for assuming the initiative. Clay, whose card-playing simile appeared to have been justified, was more depressed than elated. His 1812 speeches echoed in his ears, and he felt the demanding hands of his constituents on his shoulders. From his seldom-used pen came an article specifically calling for the temporary abandonment of impressment. Russell, of course, concurred, and Adams, after arguing both sides of the case, added his own vote and gave the Clay forces a three-to-two victory. Clay was loath to match the gesture, however, when Adams proposed status quo ante bellum —no boundary changes, no articles prohibiting impressment or clarifying neutral rights—as an alternative to be presented with the project. You could not, Clay pointed out, play “brag” after showing your hand.

Clay, of course, was yearning to try a little American finesse on the British, but he also quavered when he realized that 1815 might be nothing more than 1812 three years later—no American territory in Canada, no guarantee of neutral rights, just two or more years of running in place. One thing he would not do. He would not let the Mississippi become a British canal, as the British seemed to desire, simply to allow New England fishermen the privilege of “drying fish on a desert.” But it was Adams’ neighbors who did the fishing and Adams’ father who in 1783 had insured the right; the name of Adams would not appear on a treaty that surrendered it. Clay’s name would not be signed to a note that mentioned the Mississippi.

Adams sat tight. Clay scowled and

The American project crossed the Channel to a Cabinet still not sure of what it wanted. On Sunday, the thirteenth of November, Lord Liverpool sat brooding in Fife House—the American treaty draft and two letters from Wellington before him. The draft from Ghent, he reflected, was a studied insult, the product of beggars who did not know their own poverty. Yet from Paris—where Wellington, savior of England, was now minister to France—came an icy gust of candor. “You can get no territory,” he wrote, “indeed the state of your military operations, however creditable, does not entitle you to demand any; and you only afford the Americans a popular and creditable ground, which I believe their government are looking for, not to break off the negotiations, but to avoid to make peace.” If the Cabinet insisted, the Duke would, next year, go to America, where “I shall do you but little good”; for British claims rested with British sailors on the bottom of Plattsburg Bay.

October and November were months of misery for Liverpool. The budget watchers in Parliament were after his scalp, and taxes could go no higher. In Vienna, Castlereagh beseeched and threatened; Alexander smiled, and continued to ogle Poland; and all Europe, snickering at British reverses, softly applauded the Americans. Talleyrand wooed the Czar and glimpsed opportunity in Allied dissension. The Parisians spat at Louis, yearned for the return of Bonaparte, and cheered the American victory at Plattsburg and Prevost’s retreat into Canada.

Lord Liverpool was still digesting Wellington’s report of the cheering when the British press published the first month of the Ghent negotiations—information that the American Congress had thoughtfully provided. Englishmen were appalled and secretly admired the American resistance, and in Parliament the Opposition sharpened its knives and asked who would pay for this nonsense.

At Ghent a mortified Henry Goulburn slumped wearily into his desk chair and began his reply to Bathurst’s most recent instructions. “You know,” he wrote, bitterly, “that I was never much inclined to give way to the Americans: I am still less inclined to do so after the statement of our demands with which the negotiation opened, and which has in every point of view proved most unfortunate.” Nevertheless, he followed Bathurst’s orders directing him to oppose most of the American project, to press for navigation rights on the Mississippi, and to stay silent on the fisheries. But the hand that had reached

When they finished reading the British reaction to their project, even Adams, the eternal pessimist, thought peace was “probable.” The others were sure of it, and Clay wagered his life that the British earnestly desired a speedy conclusion. A ban on impressment and the article on indemnities for maritime spoilage were dead matters, but it is questionable that they ever really lived. There was still unfinished business, however, which, in the absence of any real obstacles, loomed large. The Americans answered on the thirtieth. On December 1, the two commissions met in their first conference since August 10. Two more meetings followed—on the tenth of December and on the twelfth.

The five Americans, more than ever, became unrelenting lawyers. They drove Goulburn and Dr. Adams, already wretched with their country’s shame, into whorls of rage. They demanded explanations which the three embarrassed Britishers were unable to provide, and messengers shuttled back and forth across the Channel. But by the beginning of the third week in December most of the points had been settled. Only three remained. The British held, claimed, and intended to keep Moose Island, a speck off the Massachusetts coast. Both sides denied the other’s rights set forth in the treaty of 1783 but demanded their own—the British their privilege of navigating the Mississippi, the Americans their fish-drying franchise. The latter two were connected in thought if not in fact, and both the fisheries and Moose Island were particular problems of Massachusetts, the home of John Quincy Adams. As Adams fought and pleaded for the rights and property of his neighbors, his neighbors were trudging to Hartford, where they intended to reform the American government or perhaps leave it.

In those first weeks of December Adams was alone to a degree that was intense even for his lifetime. He admitted that he contended for objects “so trifling and insignificant that neither of the two nations would tolerate a war for them,” but he could not go home without them. Clay, on the other hand, gagged at the thought of British ships on the Mississippi. He and Adams shouted at one another. They would not listen to compromise. They would not sign the treaty.

Bayard joined Adams in his nocturnal walks about Ghent and talked to him like a kindly Dutch uncle. Gallatin, who in every respect was now the American leader, reasoned with both Adams and Clay. He offered suggestions; he teased Adams out of some of his obstinacy; he told Clay to stop acting like a little boy; he turned their acid to humor; in despair, he shouted back at them. By December 14 Adams stood alone. His colleagues would make one more attempt, but whatever its success they would sign

A week and a day later, Bayard hurried through the streets of Ghent in search of the perambulating Adams. The British had accepted. Peace was but a detail.

The details were composed the next day, Friday, December 23, at the American house. The two commissions met at noon and arranged the procedure for the following day. At three o’clock they separated to draw up copies for signing. The Americans were not sure what to think. Clay was sullen. Gallatin said that all treaty commissions were unpopular. Adams was sure that they would be “censured and reproached” at home. Yet the five of them felt relief.

And in a few months they would be heroes. The treaty would reach Washington on February 14; two days later the Senate would vote unanimously for ratification; and on the eighteenth, President Madison would call it “highly honorable to the nation,” as, with thanks and joy, he read his proclamation. Post riders, who had already carried the news of Andrew Jackson’s glorious victory at New Orleans, would ride night and day throughout the country. They would gallop into Philadelphia on a Sunday morning as congregations streamed from their churches and steeple bells made a New Year’s Eve of the Sabbath. In rebellious Boston, school children would delight in an unexpected holiday from classes. New York would be ablaze with torchlight parades and nearly deafened by the barrage of cannon fired in gleeful celebration.

For a document that was little more than an armistice, the Treaty of Ghent had far-reaching influence. It said nothing about impressment, which was already an archaic practice, and nothing about neutrals’ rights, which would never be respected to anyone’s satisfaction. Boundary problems, territorial claims—in fact, all other disputes—were to be settled later by joint commissions. The treaty was no more than an instrument that restored the status quo , but it raised the silly little American democracy to a new level of respect in European eyes, and it brought a delicate peace between Great Britain and the United States—a peace that would eventually become a firm partnership. Fenians, explorers, Confederates, Maine potato farmers, New Brunswick roughnecks, rumrunners, tourists—all of these would, from time to time, disturb the tranquillity of the U.S.-Canadian border, but that boundary would become the longest unguarded frontier in the world. And the two belligerents of 1812 would learn, through their joint commissions, an adult way of reconciling at least some of their differences. This would be the legacy of the document that was signed at Ghent on that December 24,

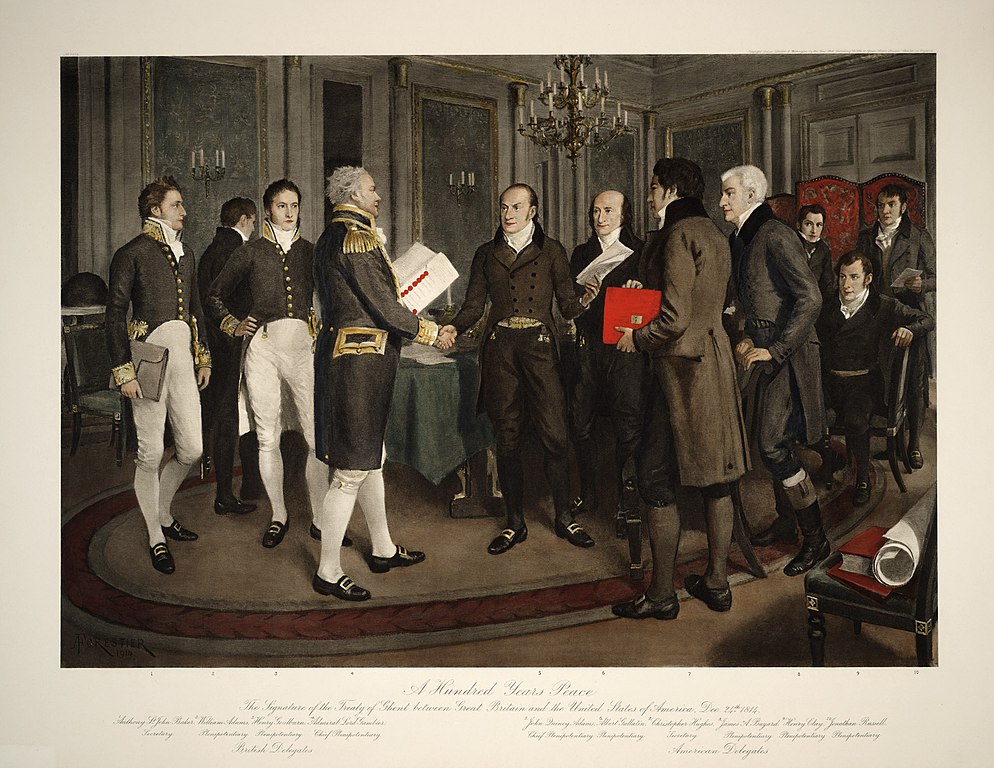

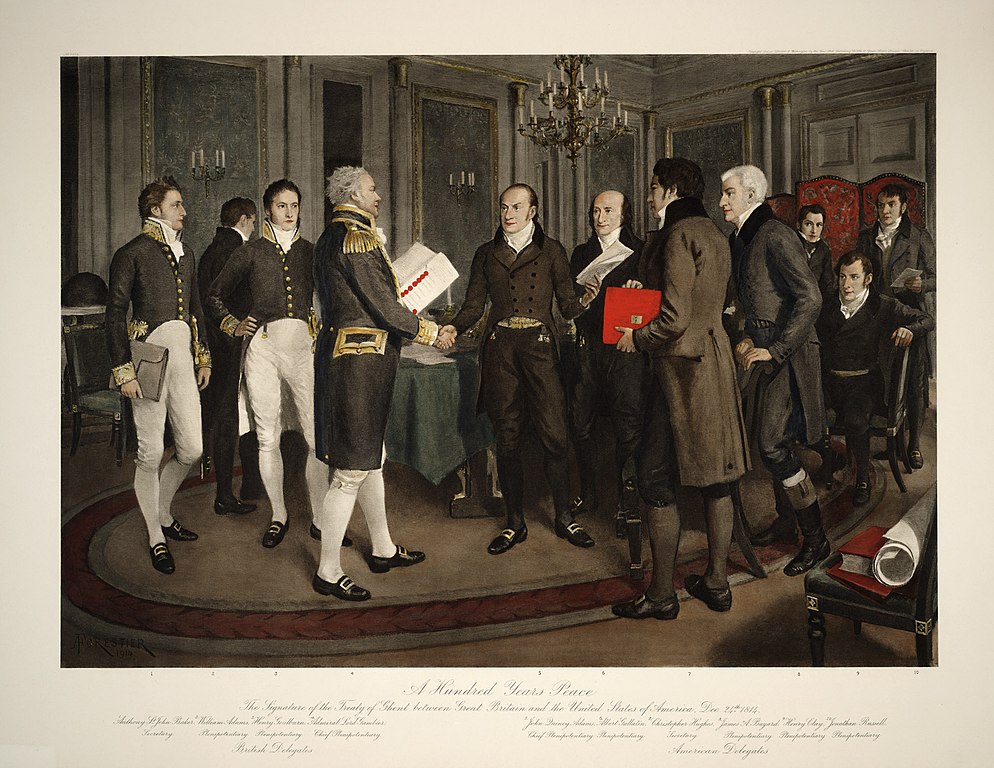

At four in the afternoon of that Christmas eve the American commission arrived at the British Chartreux, a former monastery where Napoleon had spent one of his honeymoons. In the courtyard, Baker’s carriage stood ready for the dash to Ostend, where he would take ship for London. The British greeting was almost warm, and for two hours the three Englishmen and the five Americans pored over the treaty copies and made corrections. At six, with darkness spreading over Ghent and the carillon of St. Bavon pealing its Christmas message, the eight gentlemen gathered about the long table and officially attested to a “Treaty of Peace and Amity Between His Britannic Majesty and the United States of America.” When all had signed, Lord Gambier presented the British copies to the Americans and said that he hoped the treaty would be permanent. Adams, in turn, handed over the American copies and replied that his government, too, wished that this would be the last Anglo-American treaty of peace. And at six thirty the Americans disappeared into the solemn night with peace in their pockets.