Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2009 | Volume 59, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2009 | Volume 59, Issue 1

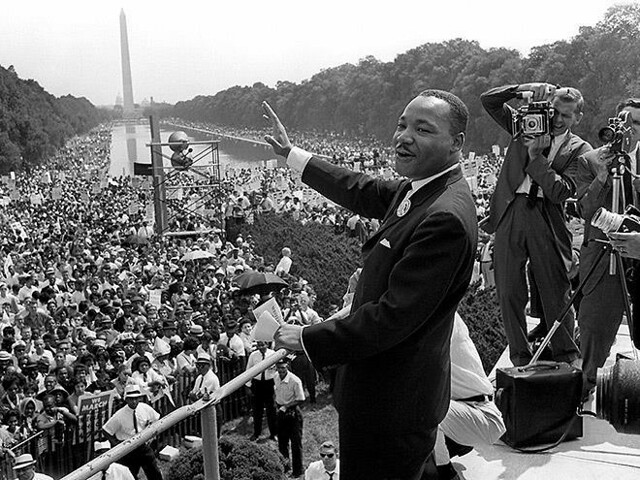

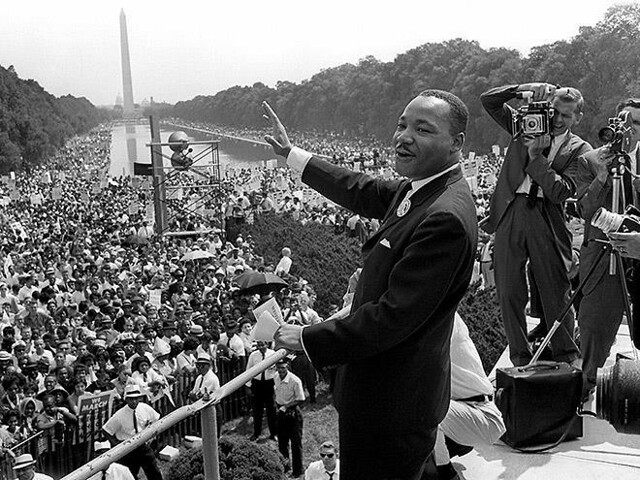

Standing in the cold with 2,000,000 others near the Capitol as Barack Obama delivered his inaugural address, I couldn’t help but recall another crowded day 45 years earlier, when I heard Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” oration at the other end of the National Mall, in front of the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

A 19-year-old college student at the time, I was moved by his words but had no idea that his speech would soon rank as one of the greatest oratories in American history. My view of King and his rhetoric would be profoundly affected in unexpected ways by the changes the march had set in motion. I wondered how Obama’s speech might affect the lives of the many young people that I saw in the crowd at the Capitol but appreciated how difficult it is to predict the enduring impact of even the most moving oratory. Nonetheless, my study of King, especially since becoming editor of his papers, has convinced me that King’s and Obama’s distinctive oratorical qualities are related in important ways. Indeed, the new president seems to personify King’s dream that his children would live in a nation capable of judging people on the basis of character rather than skin color.

In 1963, King’s dream seemed a fantasy. The continuing reality of racial discrimination and segregation made me dubious about King’s visionary rhetoric, his faith in American ideals, and his mode of charismatic leadership. King critics such as Stokely Carmichael, Bob Moses, and other organizers of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had convinced me that black advancement would come not through the guidance of national civil rights leaders such as King but through militant grassroots activism.

The landmark civil rights legislation that followed the march failed to transform Mississippi “into an oasis of freedom and justice,” as King had envisioned. During the era of Black Power and the Black Arts Movement, the idea that Americans of all races one day would join hands and sing, “Free at last, free at last,” seemed far-fetched. Malcolm X and the Black Power firebrands pushed King from prominence as they revived an alternative black nationalist oratorical tradition that offered a compelling explanation of the escalating racial violence and police repression of the late 1960s. During the last year of his life, King himself spoke of his dream turning into a nightmare; in his 1967 antiwar speech at New York’s Riverside Church, he called the American government “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.”