Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1958 | Volume 9, Issue 3

Authors: George F. Scheer

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1958 | Volume 9, Issue 3

There is the poem, and there is the sentence or two in schoolbooks about the phantom general who sallied at night I’rom his secret lair in the swamps to attack the British loe. And there is the sobriquet, the Swamp Fox. And that’s about all anyone seems to remember about General Francis Marion—except, perhaps, that once he invited to dinner a British officer, in his camp under flag of truce, and served only fire-baked potatoes on a bark slab and a beverage of vinegar and water. “But, surely, general,” the officer asked, “this cannot be your usual fare.” “Indeed, sir, it is,” Marion replied, “and we are fortunate on this occasion, entertaining company, to have more than our usual allowance.” The visiting Briton is supposed to have been so impressed that he resigned his commission and returned to England, full of sympathy for the sell-sacrificing American patriots. That’s not exactly the way it happened, but no one has ever cared much about the details; that is the way it goes in the Marion legend, and it is the legend that Americans cherish.

That legend was the invention of a specialist in hero making, and the story of its origin and growth is as remarkable as the story of the man it celebrates. It begins with one of Marion’s devoted soldiers, Peter Horry, and it tells how he undertook, several years alter Marion’s death, to write a biography that would immortalize his old chief; how he discovered himself unequal to the task and gave it up; how, much later, his accidental partnership with the Reverend Mason Locke Weems resulted in the first life of General Marion, “a celebrated partisan officer in the Revolutionary War, against the British and Tories, in South Carolina and Georgia,” drawn, according to the title page, “from documents furnished by his Brother-in-arms, Brigadier General P. Horry,” and by Marion’s nephew; how that sensational little book, a captivating melange of “popular heroism, religion, and” morality,” compounded of fact and much fiction, firmly established Francis Marion in the American imagination as the Robin Hood of the Revolution; and how, after that,

That first “biography” appeared in 1809, and the century and a half that has passed since its publication has done little to change the legendary portrait: the Marion of Parson Weems remains the Marion of American history. Yet when you piece together the surviving letters, the orderly books, the official reports, when you read the maps and go to the ground he fought over, you come to reali/e that Marion’s daring forays and breathtaking adventures are not merely the romantic stuff of folk literature, but that they actually influenced the strategy of armies and made a definite and discernible contribution to the British defeat in the South.

From the outbreak of the Revolution until the spring of 1780, Marion put in five useful, though relatively inactive, years as an officer of the Second South Carolina Continental Regiment. Hut it was as a relentless guerrilla who never let up on the British after (hey overran his state that he earned his significance in history. He was not the only partisan those hard times discovered, but he stayed in the field longer than any of the others and best understood and carried out the mission of the partisan. And, although he won no tideturning battles, he had more than a little to do with what General Nathanael Greene, commanding the Southern Department, called “flushing the bird” that General Washington caught at Yorktown.

Marion was 48 at the time, “rather below the middle stature,” one of his men recalled, “lean and swarthy. His body was well set, but his knees and ankles were badly formed. … He had a countenance remarkably steady; his nose was aquiline, his chin projecting; his forehead was large and high, and his eyes black and piercing.” It was the kind of face some men considered “hard visaged.”

He was a man with the steady habits of a modest planter who had lived alone most of his life. He ate and drank abstemiously; his voice was light but low when he talked, and that was seldom because he was not a talkative man.

In the field he wore a close, round-bodied, crimson jacket and the blue breeches piped in white of his old Continental regiment. His black leather hat was the hard, visored helmet of the Second South Carolina, adorned with a

Whether he fotight his brigade mounted or afoot—he usually rode to the enemy and then fought as infantry—he was always in the front of the attacks that made his name a terror in the Hritish and Tory camp. Mut he was not given to ferocious gesture. In fact, they say he drew his sword, a light dress weapon, so seldom that it rusted in its scabbard. It was not for personal conspicuonsness in battle that his men remembered him, but for a quiet fearlessness, for sagacity and perseverance, and for never foolishly risking himself or the brigade. They rode with confidence behind a man who never hesitated in the face of impossible odds to fight and run to live and fight another day. And he endeared himself to them when he slept with them on the ground, ate their fare, and endured fatigue and danger with the hardiesf of them. They told, for example, that one night while he slept by the Rre his helmet was scorched and his blanket half burned before he awoke. He smothered the flames, refused a blanket from any of them, and in the charred remains of his own slept out the night. For months afterward, he weathered the nights uncomplainingly under his tattered blanket and rode through sun and shower with the shriveled helmet perched jauntily on his head.

Marion’s men actually had no official status. They were purely volunteers. When they came into the field, their state was overrun by the British and their rebel government had evaporated. Of their own will they took up arms to fight the invader, and it was impossible to preserve any more discipline and regularity among them than their patriotism and the dangers of the moment imposed on them. Fighting without pay, clothing, or provisions furnished by a government, compelled to care for their families as well as to provide for their own wants, they were likely to go home at planting or harvest time, or whenever family needs became acute, or simply when the going got too dreary. Therefore, brigade strength fluctuated from as few as twenty or thirty men to as many as several hundred, and Marion had to plan his operations accordingly. He seldom could count on more than 150 to 200 men, and at least once he became so disgusted with their casual coming and going that he considered giving up his command and going to Philadelphia to seek a Continental Army appointment.

It was the constant charge by Marion’s enemies that it was not patriotism but the appeal of plunder that held his

Despite their irregularities and occasional lapses, when Marion came to disband his men in December, 1782, he could say with complete sincerity, “The general returns his warmest thanks to the officers and men who with un-wavered patience and fortitude have undergone the greatest fatigues and hardships and with a spirit and bravery which must ever reflect the highest honor on them. No citizens in the world have ever done more than they have.” It was true of them. And it was true of him.

Marion was born in the country he defended to a second-generation French Huguenot family on the Cooper River in South Carolina. As a boy he lived in the vicinity of Georgetown, where he hunted and fished the salt marshes and inland swamps and semitropical woods. When he was 23 and his father, an unsuccessful planter, died, he and his mother and a brother settled for a time in upper St. John’s, Berkeley. The tradition is that he served in a mounted troop on a bootless expedition to the Cherokee country in the first flare-up of the French and Indian War on the Carolina frontier. Two years later, as a light infantry lieutenant in Grant’s 1761 campaign against the Cherokee, he won the praise of his commanding officer as an “active, brave, and hardy soldier; and an excellent partisan officer.”

Shortly before the Revolution he acquired a place of his own on the Santce River and was just getting his bachelor house in order when war came. He was elected a captain of the Second South Carolina Regiment, steadily rose in Continental rank, served in the defense of Fort Sullivan in 1776 and the assault on Savannah in 1779, and for a time was in field command of the southern army when it wintered near the Georgia border. Through peaceful garrison times and stormy, he shared every fortune of his regiment except its last: when General Benjamin Lincoln surrendered his entire army, including the Second South Carolina, to Sir Henry Clinton at Charleston on May 12, 1780, Marion was not among the nearly 5,500 men who capitulated. For the last several weeks before the fall of the city he had been convalescing at home from an ankle injury.

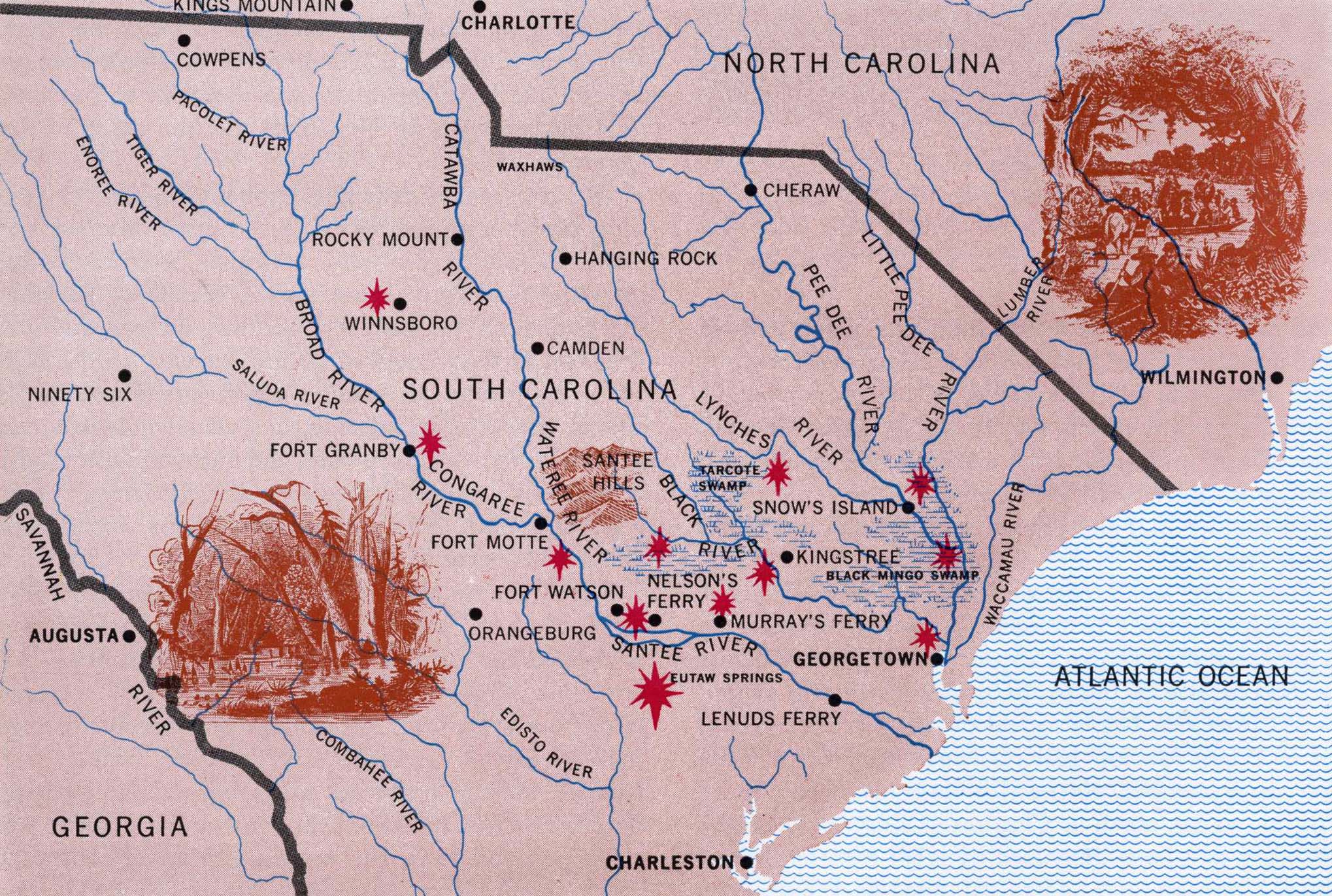

With Lincoln’s surrender, the worst disaster the Americans had suffered in all the war, the American cause both north and south seemed all but lost. In the North, Washington’s worn-out army lay deteriorating in New Jersey. The French, upon whom he had relied for reinforcements, were bottled up by a British fleet at Newport. And an enfeebled Congress and an apathetic people were allowing their rebellion to expire from sheer exhaustion. In the South Georgia had al ready been occupied by the British since the winter of iyyg, and within three weeks after Lincoln’s surrender South Carolina appeared to be totally subjugated. Without firing a shot, British garrisons occupied a chain of posts commanding the interior from Augusta on the Savannah River and Ninety-Six on the Carolina frontier, northward to Rocky Mount, Hanging Rock, and Camden, and eastward to Chcraw and Georgetown on the coast.

But to the enemy’s surprise and consternation, the paralysis that at first seized the South Carolinians was short-lived. Lord Charles Cornwallis, left by Clinton in command at Charleston when the commander in chief returned to New York, had hardly reported “everything wearing the face of tranquility and submission” when patriot guerrillas, seeming to spring from nowhere, began a fierce, harassing warfare against the conqueror, intercepting his supply trains, severing his communications, smashing British and Tory detached units.

The partisans took some encouragement from reports that a small, new Continental army had arrived in North Carolina; around this nucleus the militia of Virginia and the Carolinas might build a force strong enough to stop the northward advance of the redcoats. In late July, when his ankle would carry him, Marion rode northward to join it with a little troop of neighbors and former army comrades who felt the British had violated the paroles they had given. According to a Continental officer, they were “distinguished by small black leather caps and the wretchedness of their attire; their number did not exceed twenty men and boys, some white, some black, and all mounted, but most of them miserably equipped.” Nevertheless, General Horatio Gates, commanding the army, recognized the value of Marion’s familiarity with the country and ordered Marion and “the Volunteers Horse of So Carolina” to “march with and attend” him as he advanced toward the enemy’s key post at Camden.

While on the march, the Marion story has it, Gates received a request from Major John James for an officer to take command of a brigade he had raised among the Scotch-Irish of Williamsburg Township on the Black River. Gates promptly assigned Marion to the command with orders to use the brigade to seize the Santee River crossings behind Camden and cut off British communication with that post and its avenue of retreat to Charleston.

Marion took command of fames’s brigade on Lynche’s Creek about the tenth of August, 1780,

Near dusk he picked up a British deserter who told him that Gates’s army, upon reaching Camden. had been routed by the British on the sixteenth with in credible losses. From the deserter he also learned that a British escort with 150 Continental prisoners from Camden planned to rest that night at a house north of Nelson’s Ferry. Without sharing with his men the depressing news of Gates’s defeat, for fear they would desert him, he pushed his march all night and descended on the escort at dawn, !'rapping many of the redcoats in the house, he killed two, wounded five, took twenty prisoners, and released the captured Continentals. But Marion’s men heard from the prisoners that Gates had been defeated, and half of them slipped away within an hour. Marion, discovering that a heavy British patrol was in Iiix rear, scut his prisoners toward North Carolina and retreated eastward toward the Pee Dee to make a junction with Major Horry’s detachment.

Marion had no idea where the remnant of Gates’s army was, or when or if it would ever be in “condition to act again.” Colonel Thomas Sumter, who had bedeviled the enemy in the west, had been cut to pieces two days after the Camden debacle. Marion’s little brigade was the only rebel force left intact in the state. With most of his men gone home, he now was forced, alter a couple of brushes with enemy columns, to withdraw into North Carolina.

But within two weeks, he had heard from Gates at Hillsboro: North Carolina was aroused, the army was putting itself back together; in South Carolina Whig militia was assembling. Unfortunately, the Tories were gathering, too, and Gates would be pleased, he wrote, if Marion would advance to the Little Pee Dee River and disperse them. At the same time Marion heard from South Carolina that north of Georgetown the enemy had laid waste a path seventy miles long and fifteen wide as a punishment to the inhabitants who had “joined Marion and Horry in their late incursion”; the men who had left him at Nelson’s Kerry were spoiling for revenge and ready to come out again. So on a Sunday evening, the twenty-fourth of September, with only thirty or forty men, Marion marched back into the heart of the enemy’s northeastern-most defenses in South Carolina around Kingston.

of Robin Hood were never more devoted to their chief than were the men of Marion’s brigade to their beloved leader. Illustration courtesy of Culver Service" data-entity-type="file" data-entity-uuid="ed4191a1-54d3-4eb6-b2a2-bda456f1a60b" height="369" src="https://www.americanheritage.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/SwampFox_Horse.jpg" width="326" loading="lazy">

The marches and actions that ensued between Marion and the British and Tories are hard to follow, even on large-stale maps of the river-and-swamp country of South Carolina, and they are almost lost in the larger history of the campaigns in the South: but they were shrewdly planned, smoothly executed, and very damaging to the enemy. To them Marion brought not only the training of an officer of the regular service and the remembered’ experience of Indian-style lighting on the liontier, but also an intimate knowledge of the country. And it was the terrain that gave to the native fighter a distinct advantage. It was unbelievably flat, unbelievably wet, and unbelievably wild—this world of the low country. North and south some eighty miles from Charleston and west some fifty were its roughly figured boundaries, and down across it swept seven large rivers and many smaller ones which gave it its character. For miles bordering them were the deep, vast, and gloomy cypress swamps. And between the gieat swamps were the forbidding shrub bogs, spongy tangles of impenetrable smilax, holly, myrtle, and jessamine, and broad brakes of cane. No roads crossed the swamps and bogs, except the secret paths of the hunter; only a few highroads, following the ridges between the great rivers and passing through forests of moss-hung live oak, tied together the plantations and scattered towns. Maps were not of much use oil the main roads. But it was country that Marion knew and understood, so that for him its trails became avenues of swift surprise attack and sale retreat, its swamps and bogs his covert.

In this country during that fall of 1780, Marion’s men fought at Black Mingo, northwest of Georgetown. It was another night attack, but their horses’ hoofs clattering on a wooden bridge gave them away, so that they lost the element of surprise and learned ever after to lay down their blankets when crossing a bridge near the enemy. They raided Georgetown, but could not draw the garrison out of the town redoubt for a stand-up fight. Another night they pounced on Tory militia at Tarcote Swamp, near the forks of Black River.

It was of such incidents that Parson Weems made highly diverting tales. A friendly lad comes to (amp to tell that tomorrow night “there is to be a mighty gathering of the tories near his home, seventy miles away. “Having put our firearms in prime order for an attack, we mounted; and … dashed oil, just as the broad-faced moon arose; and by daybreak next

“Observing that they had three large Ores, Marion divided our little party of sixty men into three companies, each opposite to a fire, then bidding us to take aim. with his pistol he gave the signal for a general discharge. In a moment the woods were all in a blaze, as by a flash of lightning, accompanied by a tremendous clap of thunder. Down tumbled the dead; oil bolted the living; loud screamed the wounded: while far and wide, all over the woods, nothing was to be heard but the running of tories. …

“The consternation of the tories was so great that they never dreamt of carrying oft anything. Even their fiddles and fiddle bows, and playing cards, were all left strewed around their fires.

“One of the gamblers, (it is a serious truth) though shot dead, still held the cards hard gripped in his hands. Led by curiosity to inspect this strange sight, a dead gambler, we found that the cards which he held were ace, deuce, and jack. Clubs were trumps. Holding high, low, jack, and the game, in his own hand, lie seemed to be in a lair way to do well; but Marion came down upon him with a trump that spoiled his sport, and non-suited him forever.”

No wonder that the Parson captured the fancy of a young America!

They were small engagements, poorly chronicled, though poet-sung (“A moment in the British camp—a moment—and away, back to the pathless forest, before the peep of day.”), but as the weeks passed into winter, Lord Cornwallis began to feel the cumulative effect of them. When Marion had retreated into North Carolina in September, Cornwallis had advanced toward Virginia as far north as Charlotte before his detached left wing had been destroyed by rebel frontiersmen at Kings Mountain and he had stumbled back sixty miles to Winnsboro to recover himself. In that hamlet, northwest of Camden, he encamped lor three miserable, wet months, October to January; and his letters from there make it reasonably dear that, although much of his strength had been lost at Kings Mountain and he had to await reinforcements from New York, it was the work of the partisans, especially of Marion, that tied him to Winnsboro and prevented his moving northward again. To his superior he reported: “Had as the state of our affairs was on the northern frontier [around Ninety-Six, Rocky Mount, and Hanging Rock], the eastern part [on the vital Sautee River line] was much worse. … Colonel Marion had so wrought on the minds of the people, partly by

Lieutenant Colonel llanastre Tarleton was even more specific: “Mr. Marion, by his zeal and abilities, showed himself capable of the trust committed to his charge. He collected his adherents at the shortest notice, in the neighborhood of Dlack River, and, after making incursions into the friendly districts, or threatening the communications, to avoid pursuit, he disbanded his followers. The alarms occasioned by these insurrections frequently retarded supplies on their way to the army; and a late report of Marion’s strength delayed the junction of the recruits, who had arrived [in Charleston] from New York for the corps in the country.”

The one man Cornwallis thought capable of running down ami destroying the elusive Marion was Tarleton himself. In South Carolina, after his savage slaughter of Muford’s troops at the Waxhaws, Tarleton was known as “the Kutcher” and was without question the most bitterly hated of all the redcoats. In the British Army, where his loyalist legion was lamed for its energy, prowess, and daring, he had risen swilftly and at 26 was regarded as perhaps the most valuable leader of mounted troops. “I therefore sent Tarleton,” Cornwallis reported, “who pursued Marion for several days, obliged his corps to take to the swamps. …”

There was more to it than that. Marion led Tarleton a chase in that November of 1780. Tarleton was sixteen miles north of Nelson’s Kerry when he discovered that Marion was a lew miles south of him and struck out after him. About dark Marion cut through the Woodyard, a broad and tangled swamp, and camped for the night six miles beyond it. Tarleton dared not cross the Woodyard in the dark. As he was riding around it in the morning. Marion continued down Black River 35 miles “through woods and swamps and bogs, svhere there was no road.” Tarleton, after making his way “for seven hours through swamps and defiles,” hit 23 miles of fair road and then ran into Ux Swamp, where the chase went out of him.

Tradition has it that when Tarleton turned back (or was called off by a courier with orders to turn about and go after Sumter in the west) he gave Marion his sobriquet: “Come on, my boys, let’s go back. As for this damned old fox, the devil himself could not catch him.”

For all his pursuing, Tarleton merely gave exercise to Marion’s brigade; lor several more weeks the old fox was busily gnawing at British supply trains and posts and parties. Then, with his ammunition and supplies nearly exhausted, he took up an encampment in a romantic spot not far from the original ground of the Williamsburg men; it was called Snow’s Island

Through the rest of the winter of 1780 and into the spring of 1781, Marion played his partisan role while great events wrought great changes in the condition of the American cause in the South. In December General Nathanael Greene arrived at Charlotte to succeed Gates in command of the Continental Army of the Southern Department. By mid-April, 1781, in perhaps the most brilliant campaign of the war, he had maneuvered a greatly weakened and confused Cornwallis into Virginia and returned to South Carolina to battle for repossession of the state.

As Greene advanced toward Canidcn, Marion, joined by the splendid legion of young Light Horse Harry Lee, moved against the inner chain of British posts on the Santee and Congaree. Fort Watson, their first objective, was a tremendous, stockaded work crowning an ancient Indian mound that rose almost forty feet above the surrounding plain, north of Nelson’s Ferry on the Santee. When Marion and Lee tailed after a week to starve out the garrison by siege, they managed to effect a surrender by firing down on the fort from a log tower, devised by a country major of Marion’s brigade who probably had never heard of the warring Romans.

By May 6 when they reached Fort Motte on the Congaree, Marion and Lee had a light fieldpiece, begged from Greene’s army, but it did them no good. Fort Motte consisted of a strong stockade with outer trenches and an abatis built about a handsome brick mansion on a commanding piece of ground. They spent six days digging parallels and trenches and mounting their gun, but the fieldpiece failed to make a tient in the heavy timbers of the stockade or the walls of the house. Again the attackers resorted to primitive methods. Getting up close under cover of the siege lines, a man of Marion’s brigade Hung ignited pitch balls on the roof, set it afire, and smoked the enemy out. That night Mrs. Rebecca Motte, who had taken residence in her overseer’s cottage when the British confiscated her house, entertained both the victors and the vanquished at what Colonel Lee called “a sumptous dinner.”

One by one the British posts fell. After repulsing Greene, the British evacuated Camden. Augusta surrendered, and Fort Granby. The British blew up their own fort at Nelson’s Ferry. Marion dashed to Georgetown and this time took it. Greene himself unsuccessfully laid siege to Ninety-Six, but the

Late in August Greene came down from the High Hills to fight his last pitched battle of the war, at Eutaw Springs near Nelson’s Ferry, on September 8. For the first time since the assault on Savannah in 1779, Marion found himself in formal battle, in command of the right wing of Greene’s front line. The whole first line was made up of North and South Carolina militia. It must have seemed strange to Marion’s partisans to be there. But for once militia did not panic; before falling back under enemy pressure they delivered seventeen rounds and wrung from Greene praise for a firmness that he said “would have graced the veterans of the great King of Prussia.”

It was pretty much a drawn battle. Both sides retreated. But Greene had damaged the British so severely that soon they withdrew into their lines at Charleston and never emerged again.

Though Whigs and Tories murdered each other with unrelenting bitterness for more than a year longer, and hard-hitting raids took men slashing and shooting through the swamplands, and Marion added more names to his roster of fights, the question of ultimate victory in the South was settled. On the day following the battle of Eutaw Springs, a French fleet returned to Chesapeake Bay in Virginia and sealed the fate of the ambitious English earl whom Greene had driven into a faraway trap at a village called Yorktown.

In December of the next year, 1782, under the gnarled live oaks at Wadboo plantation, Marion discharged his brigade, its mission accomplished.

Today many of Marion’s battle sites are under man-made lakes, sacrificed to the need for water power. Others are long lost under towns and roads and domesticated fields, and others simply cannot be identified. But the old maps show where he rode and the brittle documents tell what he did, and it was a magnificent performance.

After the war Marion married his cousin and lived out his last years in comfort as a small planter on the Santee. When he died in 1795, it made scarcely a stir; he was simply another old officer of the Revolution. So, perhaps, it was justice, after all, that Parson Weems came along.