Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1958, Summer 2025 | Volume 10, Issue 1

Authors: Malcolm Cowley

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1958, Summer 2025 | Volume 10, Issue 1

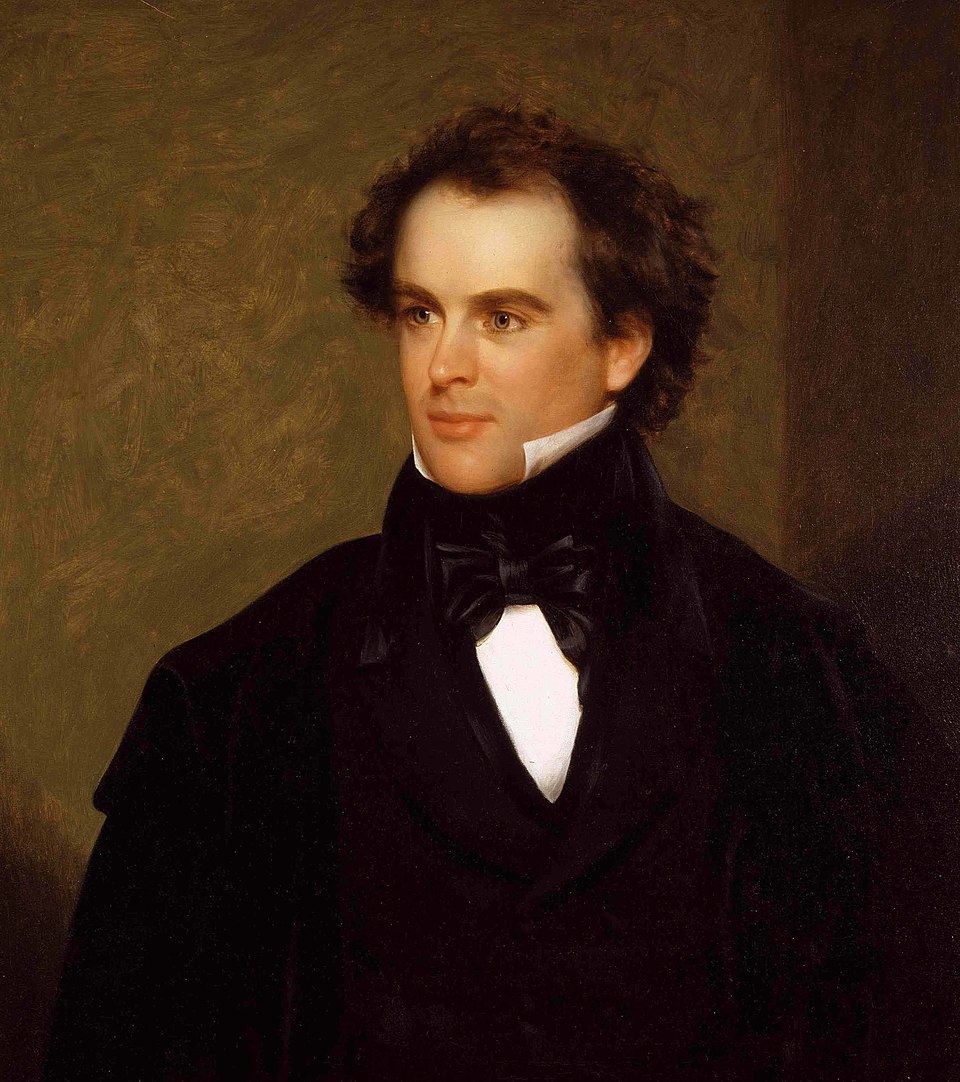

There are only a few great love stories in American fiction, and there are fewer still in the lives of famous American writers. Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote one of the greatest, The Scarlet Letter. He also lived a story that deserves to be retold—with all the new knowledge we can bring to bear on it—as long as there are lovers in New England; it was his courtship and conquest of Sophia Peabody. Unlike his first novel, the lived story was neither sinful nor tragic. Everything in the foreground was as softly glowing as a June morning in Salem, but there were shadows in the background and obstacles to be surmounted; among them were poverty, seemingly hopeless invalidism, conniving sisters, political intrigues, a silken temptress, a duel that might have been fought to the death, and inner problems more threatening than any of these. It was as if Hawthorne had needed to cut his way through a forest of thorns—some planted by himself—in order to reach the castle of Sleeping Beauty and waken her with a kiss, while, in the same moment, he wakened himself from a daylong nightmare.

When he first met Sophia, Hawthorne was thirty-three years old, and he had spent twelve of those years in a dreamlike seclusion. Day after day he sat alone in his room, writing or reading or merely watching a sunbeam as it bored through the blind and slowly traveled across the opposite wall. “For months together,” he said long afterward, in a letter to the poet R. H. Stoddard, “I scarcely held human intercourse outside of my own family; seldom going out except at twilight, or only to take the nearest way to the most convenient solitude.” He doubted whether twenty people in Salem even knew of his existence.

In remembering those years, Hawthorne sometimes pictured his solitude as being more nearly absolute than it had been. There were social moments even then. Every summer he took a long trip on his Manning uncles’ stagecoach lines and “enjoyed as much ol liie,” he said, “as other people do in the whole year’s round.” In Salem he made some whist-playing acquaintances and learned a little about the intricacies of Democratic party politics. He had a college friend, Horatio Bridge, of Augusta, Maine, to whom he wrote intimate letters, and Bridge was closely connected with two rising political figures, also Democrats and college friends of Hawthorne’s, Congressman Jonathan Cilley of Maine, and Franklin Pierce, the junior senator from New Hampshire. All three were trying to advance Hawthorne’s career, and Bridge had rescued him from complete

After the book appeared in the early spring of 1837, its author made some mild efforts to emerge into Salem society, where the young ladies admired him tor his courtesy, his deep-set eyes—so blue they were almost black—and his air of having a secret life. He thought of marriage and even fancied himself in love that spring, as Romeo did before meeting Juliet, but his courtship of a still-unidentified woman was soon broken off. Hawthorne was beginning to tear that he would never be able to rejoin the world of living creatures. His true solitude was inward, not outward, and he had formed the habit of holding long conversations with himself, like a lonely child. His daylong nightmare was of falling into a morbid state of selfabsorption that would make everything unreal in his eyes, even himself. “None have understood it,” says one of his heroes, Gervayse Hastings of “The Christmas Banquet,” who might be speaking for the author, “—not even those who experience the like. It is a chilliness—a want of earnestness—a feeling as if what should be my heart were a thing of vapor—a hauntin perception of unreality! … All things, all persons … have been like shadows flickering on the wall.” Then putting his hand on his heart, he says, “Minemine is the wretchedness! This cold heart …”

Sophia Amelia Peabody, five years younger than Hawthorne, never suffered from self-absorption or an icy heart, but she had a serious trouble of lier own. A pretty rather than a beautiful woman, with innocent gray eyes set wide apart, a tiptilted nose, and a mischievous smile, she had beaux attending her whenever she appeared in society; the trouble was that she could seldom appear. When Sophia was fifteen, she had begun to suffer from violent headaches. Her possessive mother explained to her that suffering was woman’s peculiar lot, having something to do with the sin of Eve. Her ineffectual father had her treated by half the doctors in Boston, who prescribed, among other remedies, laudanum, mercury, arsenic, hyoscyamus, homeopathy, and hypnotism, but still the headaches continued. Once as a desperate expedient she was sent to Cuba, where she spent two happy years on a plantation while her quiet sister Mary tutored the planter’s children. Now, back in Salem with the family—where her headaches were always worse—she was spending half of each day in bed. Like all the Peabody women, she had a New England conscience and a firm belief in the True, the Beautiful, and the Transcendental. She also had a limited but genuine talent for painting. When she was strong enough, she worked hard at copying pictures—and the copies sold- or at painting romantic landscapes of her own.

Sophia had been cast by her family in a role from which it seemed unlikely that she would ever escape. Just as Elizabeth Peabody was the intellectual sister, already famous as an educational reformer, and Mary was the quiet sister who did most of the household chores, Sophia was the invalid sister, petted like a child and kept in an upstairs room. There were also three brothers, one of them married, but the Peabodys were a matriarchy and a sorority; nobody paid much attention to the Peabody men. It was written that when the mother died, Sophia would become the invalid aunt of her brother’s children; she would support herself by painting lampshades and firescreens, while enduring her headaches with a brave smile. As for Hawthorne, his fate was written too; he would become the cranky New England bachelor, living in solitude and writing more and more nebulous stories about other lonely souls. But they saved each other, those two unhappy children. Each was the other’s refuge, and they groped their way into each other’s arms, where both found strength to face the world.

It was Elizabeth, the intellectual sister, who first brought them together, unthinkingly, in a moment of triumph for herself. She had long admired a group of stories, obviously by one author, that had been appearing anonymously in the annual editions of a gift book, The Token, and in the New England Magazine. Now she learned that the author was a Salem neighbor. Always eager to inspire a new genius, she made patient efforts to inveigle him into the Peabody house on Charter Street, with its square windows looking over an old burying ground where Peabodys and Hathornes—as the name used to be spelled—were sleeping almost side by side. She even took the bold step of paying several visits to the Hawthorne house on Herbert Street, known as “Castle Dismal,” where nobody outside the family had dared to come for years.

Usually she was received by Hawthorne’s younger sister, Louisa, who, Miss Peabody said disappointedly, was “quite like everybody else.” The older sister, Elizabeth—usually tailed Ebe—was known with good reason as “the hermitess,” but she finally consented to take a walk with her enterprising neighbor. Madam Hawthorne, the mother, stayed in her room as always, and Nathaniel was nowhere to be seen. He did, however, send Miss Peabody a presentation copy of his book, and she replied by suggesting some journalistic work that he had no intention of doing. Then, on the evening of November 11, 1837, came her moment of triumph. Elizabeth was sitting in the parlor, looking at a five-volume set of Flaxman’s classical engravings that she had just been given by Professor FeIton of Harvard, when she heard a great ring at the front door.

“There stood your father,” she said half a century later in a

Sophia laughed and said, “I think it would be rather ridiculous to get up. If he has come once he will come again.”

A few days later he came again, this time in the afternoon. “I summoned your mother,” Miss Peabody said in the same letter, “and she came down in her simple white wrapper, and glided in at the back door and sat down on the sofa. As I said, 'My sister, Sophia—Mr. Hawthorne,' he rose and looked at her—he did not realize how intently, and afterwards, as we went on talking, she would interpose frequently a remark in her low sweet voice. Every time she did so, he looked at her with the same intentness of interest. I was struck with it, and painfully. I thought, what if he should fall in love with her…”

Miss Peabody explained why that was a painful thought; it was because “I had heard her so often say, nothing would ever tempt her to marry, and inflict upon a husband the care of such a sufferer.” But there was an unspoken reason too, for it is clear from other letters that Elizabeth Peabody wanted Nathaniel Hawthorne for herself. Whether she hoped to marry him we cannot be sure, but there is no question that she planned to become his spiritual guide, his literary counselor, his muse and Egeria.

Sophia had no such clear intentions. She told her children long afterward that Hawthorne’s presence exerted a magnetic attraction on her from the beginning, and that she instinctively drew back in self-defense. The power she felt in him alarmed her; she did not understand what it meant. By degrees her resistance was overcome, and she came to realize that they had loved each other at first sight… That was Sophia’s story, and Hawthorne did not contradict her. There is some doubt, however, whether he told her about everything that happened during the early months of their acquaintance.

What followed their first meeting was a comedy of misunderstandings with undertones of tragedy. Hawthorne was supposed to be courting Elizabeth—Miss Peabody, as she was called outside the household; the Miss Peabody, as if she had no sisters. There was a correspondence between them. In one of her missives—and that is the proper word for them—she warned Hawthorne that her invalid sister would never marry. His answer has been

The story of his involvement, and of the duel to which it nearly led, was told in some detail by Julian Hawthorne in his biography of his parents. Unfortunately Julian did not give names (except “Mary” and “Louis”) or offer supporting evidence. Poor Julian, who was sometimes irresponsible, has never been trusted by scholars, and the result is that later biographers of Hawthorne either questioned the story or flatly rejected it. Quite recently Norman Holmes Pearson of Yale, who is preparing the definitive edition of Hawthorne’s letters, discovered an interesting document in the Morgan Library. He wrote an article about it for the Essex Institute’s quarterly, one for which other scholars stand in his debt. The article was a memorandum by Julian on a conversation with Miss Peabody, one in which she described the whole affair, giving names and circumstances and supporting Julian’s story at almost every point. She even explained by implication why the principal figures in the story had to be anonymous. Two of them were still living in 1884, when Julian’s book was published, and one of them was the widow of a president of Harvard.

Her name when Hawthorne knew her was Mary Crowninshield Silsbee, and she was the daughter of former United States Senator Nathaniel Silsbee, a great man in New England banking and shipping. Julian says that she was completely unscrupulous, but admits that she had “a certain kind of glancing beauty, slender, piquant, ophidian, Armida-like.” Armida—in Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered—was a heathen sorceress, daughter of the king of Damascus, who lured the boldest of the Crusaders into her enchanted garden. Mary Silsbee exercised her lures on the brilliant young men she met in her travels between Salem and Washington. One of them was John Louis O’Sullivan of Washington, who was laying ambitious plans for a new magazine to be called the Democratic Review.

The young editor was a friend of Hawthorne’s classmate Jonathan Cilley, the rising congressman from Maine. Cilley had given him a copy of Twice-Told Tales as soon as the book appeared. O’Sullivan was impressed by it and

Her method of operation was to cast herself on Hawthorne’s mercy by revealing what she told him were the secrets of her inmost soul. She read him long and extremely private passages from her diary—”all of which,” Julian says, “were either entirely fictitious, or such bounteous embroideries on the bare basis of reality, as to give what was mean and sordid an appearance of beauty and a winning charm.” Hawthorne, who had never considered the possibility that a Salem young lady might be a gratuitous liar, began to regard himself as Miss Silsbee’s protector and champion. But he disappointed her by offering none of his own confidences in return.

She tried a new stratagem. Early in February, 1838, she summoned Hawthorne to a private and mysterious interview. With a great deal of calculated reluctance she told him that his friend O’Sullivan, “presuming upon her innocence and guilelessness”—as Julian tells the story—“had been guilty of an attempt to practise the basest treachery upon her; and she passionately adjured Hawthorne, as her only confidential and trusted friend and protector, to champion her cause.” Hawthorne promptly wrote a letter to O’Sullivan, then in Washington, and challenged him to a duel. The letter has disappeared, but there is another to Horatio Bridge written on February 8—possibly the same day—in which he speaks darkly of a rash step he has just taken.

O’Sullivan must have discussed the challenge with their friend Jonathan Cilley; then he wrote a candid and friendly letter to Hawthorne refusing the challenge. But he did more than that; he made a hurried trip to Salem and completely established his innocence of the charge against him. Although Hawthorne could scarcely bring himself to believe that Miss Silsbee had made an utter fool of him, he had to accept the evidence. In Miss Peabody’s words, he called on Armida and “crushed her.”

To this point the story had been a comedy, or even a farce, but it soon had a tragic sequel on the national scene. In 1838 the House of Representatives was equally divided between conservatives and radicals, not to mention the other division between southerners and northern antislavery men. Jonathan Cilley was a rising leader among the radical free-soil Democrats, and there are some indications that his political enemies had decided to get rid of him. On a flimsy pretext, he was challenged to a duel by a fire-eating southern congressman, William J. Graves of Kentucky. He was still hesitating whether to accept the challenge when somebody said to him—according to Julian’s story—"If Hawthorne was so ready to fight a duel without stopping to ask questions, you certainly need not hesitate.” Horatio Bridge denied this part of the story, but there is no doubt that Hawthorne

Hawthorne brooded over the duel for a long time. His memorial of Cilley, which was among the first of his many contributions to the Democratic Review, reads as if he were making atonement to the shade of his friend. In a somewhat later story, “The Christmas Banquet,” from which I have quoted already, he describes a collection of the world’s most miserable persons. One of them is a man of nice conscience, who bore a blood stain in his heart—the death of a fellow-creature—which, for his more exquisite torture, had chanced with such a peculiarity of circumstances, that he could not absolutely determine whether his will had entered into the deed or not. Therefore, his whole life was spent in the agony of an inward trial for murder.

Julian’s story would lead us to believe that Hawthorne, once again, was thinking of himself.

There were other causes for worry in those early months of 1838, when Hawthorne was still supposed to be courting Sophia’s intellectual sister. One of the chief causes was Mary Silsbee, who refused to let him go. Miss Peabody’s memorandum says that Mary somehow “managed to renew relations with him,” and that she then offered to marry him as soon as he was earning $3,000 a year, a large income for the time. Hawthorne answered that he never expected to have so much. When his sister Ebe heard the story, she remarked—according to Miss Peabody—“that he would never marry at all, and that he would never do anything; that he was an ideal person.” But Hawthorne did something to end the affair; he disappeared from Salem.

Before leaving town on July 23, he paid what was known as a take-leave call on Sophia. “He said he was not going to tell any one where he should be for the next three months,” she told Elizabeth in a letter; “that he thought he should change his name, so that if he died no one would be able to find his gravestone. … I feel as if he were a born brother. I never, hardly, knew a person for whom I had such a full and at the same time perfectly quiet admiration.”

At the end of September when Hawthorne came back to Salem—from North Adams, his mysterious hiding place—Miss Silsbee had disappeared from his life. She had renewed her acquaintance with another suitor, now a widower of 49 with an income well beyond her minimum requirement; he was Jared Sparks, the editor of George Washington’s papers, who would become president of Harvard. Hawthorne now had more time to spend at the house on Charter Street. He was entertained by whichever sister happened to be present, or by all three together, but it began to be noticed that his visits were longer if he found Sophia alone. One day she showed him an illustration she had drawn, in the Flaxman manner, for his story “The Gentle Boy.” It showed the boy asleep under the tree on which his Quaker father had been hanged.

“I want to know if this looks like your Ibrahim,” she said.

Hawthorne said, meaning every word, “He will never look otherwise to me.”

Under the Peabody influence, he was becoming almost a social creature. There was a sort of literary club that met every week in one of the finest houses on Chestnut Street, where the Salem merchants lived. The house belonged to Miss Susan Burley, a wealthy spinster who liked to patronize the arts. Hawthorne was persuaded to attend some of Miss Burley’s Saturday evenings—usually as an escort for Mary or Elizabeth, since the invalid sister was seldom allowed to venture into the night air. There was one particularly cold evening when Sophia insisted that she was going to Miss Burley’s whether or not she was wanted. Hawthorne laughed and said she was not wanted; the cold would make her ill. “Meanwhile,” Sophia reported in a letter, “I put on an incalculable quantity of clothes. Father kept remonstrating, but not violently, and I gently imploring. When I was ready, Mr. Hawthorne said he was glad I was going. … We walked quite last, for I seemed stepping on air.”

The evening at Miss Burley’s marked a change in their relations. From that time Sophia began taking long walks with Mr. Hawthorne in spite of the winter gales. Elizabeth was busy with her affairs in Boston, and Mary, the quiet sister, looked on benevolently. Sophia never feIt tired so long as she could hold Mr. Hawthorne’s arm. It was during one of their walks, on a snowy day just before or after New Year’s, 1839, that they confessed their love for each other. Clinging together like children frightened of being so happy, they exchanged promises that neither of them would break. They were married now “in the sight of God,” as old-fashioned people used to say, and as Hawthorne soon told Sophia in slightly different words, but that was

In the middle of January Hawthorne went to work as a weigher and gauger for the Boston Custom House. It was a political appointment made by the collector of the port, who was George Bancroft, the historian. Hawthorne had been recommended to him by several influential persons, including Miss Peabody, who may have hoped to get him out of Salem. Bancroft justified the appointment to Washington by writing that Hawthorne was “the biographer of Cilley,” and thus a deserving Democrat. Cilley again. … It was as if the college friend for whose death Hawthorne felt responsible had reached out of the grave to help him. Many other deserving Democrats had sought for the post, but it was not a sinecure, and he worked as hard as Jacob did for Rachel, while saving half his salary of $1,500 a year. Every other Saturday he took the cars to Salem and spent an evening with Sophia. On the Saturdays in Boston he sent her a long letter, sometimes written in daily installments.

“What a year the last has been!” he wrote on January 1, 1840. “… It has been the year of years —the year in which the flower of our life has bloomed out—the flower of our life and of our love, which we are to wear in our bosoms forever.” Three days later he added, “Dearest, I hope you have not found it impracticable to walk, though the atmosphere be so wintry. Did we walk together in any such weather, last winter? I believe we did. How strange, that such a flower as our affection should have blossomed amid snow and wintry winds—accompaniments which no poet or novelist, that I know of, has ever introduced into a love-tale. Nothing like our story was ever written—or ever will be—for we shall not feel inclined to make the public our confidant; but if it could be told, methinks it would be such as the angels might delight to hear.”

As a matter of fact, Hawthorne wrote the story from day to day, in that series of heartfelt letters to Sophia, and the New England angels would delight to read them. It is true that the tone of them is sometimes too reverent for the worldly taste of our century. “I always feel,” Hawthorne says in July, 1839, “as if your letters were too sacred to be read in the midst of people, and (you will smile) I never read them without first washing my hands.” We also smile, but in a different spirit from Sophia’s. We feel a little uncomfortable on hearing the pet names with which he addresses her, almost all superlatives: “Dearissima,” “mine ownest love,” “Blessedest,” “ownest Dove,” “best, beautifullest, belovedest, blessingest of wives.” It is confusing to find that he calls her “mine own wife,” and himself “your husband” or “thy husband,” for three years before the actual marriage. His use of “thee” and “thou” in all the

Long afterward Sophia, then a widow, tried to delete the passion before she permitted the letters to be read by others. She scissored out some of the dangerous passages, and these are gone forever. Others she inked out carefully, and most of these have been restored by the efforts of Randall Stewart—the most trustworthy biographer of Hawthorne—and the staff of the Huntington Library. They show that Hawthorne was less of an other-worldly creature than Miss Peabody pictured him as being. “Mine own wife,” he says in one of the inked-out passages (November, 1839), “what a cold night this is going to be! How I am to keep warm, unless you nestle close, close into my bosom, I do not by any means understand—not but what I have clothes enough on my mattress—but a husband cannot be comfortably warm without his wife.” There is so much talk of beds and bosoms that some have inferred, after reading the restored text, that Hawthorne and Sophia were lovers for a long time before their marriage—and most of these readers thought no worse of them. But the records show that this romantic notion has to be dismissed. Much as Hawthorne wanted Sophia, he also wanted to observe the scriptural laws of love. “Mr. Hawthorne’s passions were under his feet,” Miss Peabody quoted Sophia as saying. If he had made Sophia his mistress, he would have revered her less, and he would have despised himself.

“I have an awe of you,” he wrote her, “that I never felt for anybody else. Awe is not the word, either, because it might imply something stern in you; whereas—but you must make it out for yourself. … I suppose I should have pretty much the same feeling if an angel were to come from Heaven and be my dearest friend. … And then it is singular, too,” he added with his Salem obduracy, “that this awe (or whatever it is) does not prevent me from feeling that it is I who have charge of you, and that my Dove is to follow my guidance and do my bidding.” He had no intention of submitting to the Peabody matriarchs. “And will not you rebel?” he asked. “Oh, no; because I possess the power to guide you only so far as I love you. My love gives me the right, and your love consents to it.”

Sophia did not rebel, but the Peabodys were confirmed idealists where Hawthorne was a realist, and sometimes she tried gently to bring him round to their higher way of

But this conflict of wills is a minor note of comedy in the letters. In time Sophia learned to yield almost joyfully, not so much to Hawthorne’s unmalleable nature as to his love. It is love that is the central theme of the letters—unquestioning love, and beneath it the sense of almost delirious gratitude that both of them felt for having been rescued from death-in-life. Sophia refused to worry about her health. “If God intends us to marry,” she said to Hawthorne, “He will let me be cured; if not, it will be a sign that it is not best.” She depended on love as her physician, and imperceptibly, year by year, the headaches faded away. As for Hawthorne, he felt an even deeper gratitude for having been rescued from the unreal world of self-absorption in which he had feared to be imprisoned forever. “Indeed, we are but shadows,” he wrote to Sophia, “—we are not endowed with real life, and all that seems most real about us is but the thinnest substance of a dream—till the heart is touched. That touch creates us—then we begin to be. …” In the same letter he said:

His four novels, beginning with The Scarlet Letter, were written after his marriage and written because Sophia was there to read them. Not only Nathaniel Hawthorne but the world at large owes the gentle Sophia more than can be expressed.

When Miss Peabody was told of the engagement, after more than a year, she took the news bravely. Her consolation was that having Hawthorne as a brother-in-law might be almost as rewarding as having him for a husband; she could still be his Egeria. Not yet knowing

The post in the Boston Custom House did not solve the problem. It left him with little time alone or energy for writing, and he could not be sure of keeping it after the next election. Hawthorne resigned at the end of 1840, a few months before he would have been dismissed—as were almost all his colleagues—by the victorious Whigs. After some hesitation he took a rash step, partly at the urging of Miss Peabody. He invested his Custom House savings in George Ripley’s new community for intellectual farmers: Brook Farm. It was the last time he would accept her high-minded advice.

The dream was that Hawthorne would support himself by working in the fields only a few hours each day, and only in the summer; then he could spend the winter writing stories. He and Sophia would live in a cottage to be built on some secluded spot. Having bought two shares of stock in the community at $500 each—later he would lend Ripley $400 more—he arrived at Brook Farm in an April snowstorm. Sophia paid him a visit at the end of May. “My life—how beautiful is Brook Farm!” she wrote him on her return. “… I do not desire to conceive of a greater felicity than living in a cottage, built on one of those lovely sites, with thee.” But Hawthorne, after working for six weeks on the manure pile—or gold mine, as the Brook Farmers called it—was already disillusioned. “It is my opinion, dearest,” he wrote on almost the same day, “that a man’s soul may be buried and perish under a dungheap or in a furrow of the field, just as well as under a pile of money.” By the middle of August he had decided to leave Brook Farm. “Thou and I must form other plans for ourselves,” he told Sophia; “for I can see few or no signs that Providence purposes to give us a home here. I am weary, weary, thrice weary of waiting so many ages. Yet what can be done? Whatever may be thy husband’s gifts, he has not hitherto shown a single one that may avail to gather gold.”

“Thy husband” and “mine own wife” were drawing closer to marriage, simply because they had exhausted their vast New England patience. “Words cannot tell,” Sophia had written, “how immensely my spirit demands thee. Sometimes I almost lose my breath in a vast heaving toward thy heart.” Hawthorne, now vegetating in Salem—while the Peabodys were in Boston, where Elizabeth had opened a bookshop—was looking desperately for any sort of literary work. In March, 1842, he went to Albany

The wedding was set for the last day of June. During a visit to the Emersons, Miss Peabody found a home for the young couple; it was the Ripley house in Concord, where the parson used to live. Hawthorne could no longer defer telling his family about the engagement, after keeping it secret for three years. Now at last it became evident that there was and had always been another obstacle to his marriage.

The final obstacle was his older sister, Ebe the hermitess. She adored her handsome brother and clung to him as her only link with the world. The stratagem she found for keeping him was to insist that their mother would die of shock if she learned that he was marrying an invalid. Hawthorne loved his mother, though he had never been able to confide in her. This time he finally took the risk. “What you tell me is not a surprise to me,” Madam Hawthorne said, “… and Sophia Peabody is the wife of all others whom I would have chosen for you.” When Ebe had recovered from her fury at hearing the news, she wrote Sophia a frigid letter of congratulation.

There would be, in fact, no intercourse with Ebe. She retired to a farmhouse in Beverly, where she spent the rest of her long life reading in her room and walking on the shore.

Three weeks before the date set for the wedding, Sophia terrified everyone by taking to her bed. There was talk of an indefinite postponement. Fortunately a new doctor explained that it was nothing unusual for a bride to run a fever, and so another date was chosen: Saturday morning, July 9. It was a few days after Hawthorne’s thirty-eighth birthday, while Sophia was almost thirty-three. At the wedding in the parlor behind Miss Peabody’s bookshop, there were only two guests outside the immediate family. It started to rain as the bride came down the stairs, but then the sun broke through the clouds and shone directly into the parlor. Hawthorne and Sophia stepped into a carriage and were driven across the Charles River, along the old road through

And so they lived happily ever after? They lived happily for a time, but as always it came to an end, and the lovers too. For Hawthorne after twenty years of marriage, the end was near when he went feebly pacing up and down the path his feet had worn along the hillside behind his Concord house, while he tried to plan a novel that refused to be written. For Sophia the end was a desolate widowhood without the man who, she never ceased to feel, “is my world and all the business of it.” But the marriage was happy to the end, and at the beginning of it, during their stay at the Old Manse, they enjoyed something far beyond the capacity of most lovers to experience: three years of almost unalloyed delight.

On the morning after their first night in the Old Manse, Hawthorne wrote to his younger sister, Louisa, the one who was quite like everybody else. “Dear Louse,” he said affectionately, “The execution took place yesterday. We made a Christian end, and came straight to Paradise, where we abide at the present writing.” Sophia had the same message for her mother, although she expressed it more ecstatically. “It is a perfect Eden round us,” she said. “Everything is as fresh as in first June. We are Adam and Eve and see no persons round! The birds saluted us this morning with such gushes of rapture, that I thought they must know us and our happiness.” The Hawthornes at 38 and 33 were like children again—like children exploring a desert island that every day revealed new marvels. Their only fear was that a ship might come to rescue them. Once the great Margaret Fuller wrote them and suggested that another newly married couple, her sister Ellen and Ellery Channing, might board with them at the Manse. Hawthorne sent her a tactful letter of refusal. “Had it been proposed to Adam and Eve,” he said, “to receive two angels into their Paradise, as boarders, I doubt whether they would have been altogether pleased to consent.” The Hawthornes were left happily alone with Sarah the maid and Pigwiggin the kitten.

They were exercising a talent that most New Englanders never acquire, that of living not in the past or in dreams of the future, but in the moment itself, as if they were already in heaven. Sophia wrote letters each morning or painted in her studio, while Hawthorne worked meditatively in the garden that Henry Thoreau had planted for them. In the afternoon they explored the countryside together or rowed on the quiet river, picking waterlilies. Hawthorne wrote in his journal, “My life, at this time, is more like that of a boy, externally, than it has been since I was really a boy. It is usually supposed that the cares of life come with matrimony; but I seem to have cast off all care, and live with as much easy trust

Sometimes they ran foot races down the lane, which Sophia grandly called “the avenue.” Sometimes in the evening she wound the music box and, forgetting her Puritan training, danced wildly for her lover. “You deserve John the Baptist’s head,” he teased her. In the records of that time—there are many of them, and all a delight to read—there is only one hint of anything like a quarrel. It arose when one of their walks led them to an unmown hayfield. Hawthorne, who had learned about haying at Brook Farm, told Sophia not to cross it and trample the grass. “This I did not like very well and I climbed the hill alone,” Sophia wrote in the journal they were keeping together.

There was some thunder and lightning even during those three sunny years at the Old Manse. Sophia’s mother and her sister Elizabeth had insisted that she must never bear children, but she longed for them ardently. One day in the first February she fell on the ice—where she had been sliding while Hawthorne skated round her in flashing circles—and suffered a miscarriage. When her first baby was born in March, 1844, it lingered, as Hawthorne said, “ten dreadful hours on the threshold of life.” It lived and the parents rejoiced, but now they had financial worries: O’Sullivan took years to pay for the stories he printed, and Ripley hadn’t returned the money advanced to Brook Farm. There were weeks when Hawthorne was afraid to walk into Concord for the mail, lest he meet too many of his creditors. Sophia’s love did not waver, then or for the rest of her life, nor did her trust in the wisdom and mercy of Providence. It had snatched her from invalidism and spinsterhood and transported her to Paradise. It had made her “as strong as a lion,” she wrote to her sister Mary, “as elastic as India rubber, light as a bird, as happy as a queen might be,” and it had given her a husband whose ardent love was as unwavering as her own. She was expressing in five words all her faith in Providence, and indeed all her experience of life, when she stood at the window in Hawthorne’s study one April evening at sunset and wrote with her diamond ring on one of the tiny panes —for him to see, for the world to remember: