Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1957, Summer 2025 | Volume 8, Issue 3

Authors: William Harlan Hale

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1957, Summer 2025 | Volume 8, Issue 3

On Saturday morning, October 25, 1851, Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, entrenched after a decade of existence as America’s leading Whig daily, appeared with twelve pages rather than its usual eight. The occasion was too noteworthy to be passed over without comment by the paper itself. So a special editorial was written — probably by Greeley’s young managing editor, the brisk, golden-whiskered Charles A. Dana — to point it out.

Besides a “press of advertisements,” the editorial ran, this morning’s enlarged paper contained “articles from some foreign contributors that are especially worthy of attention.” Among these were “a letter from Madame Belgioioso, upon the daily and domestic life of the Turks, and another upon Germany by one of the clearest and most vigorous writers that country has produced—no matter what may be the judgment of the critical upon his public opinions in the sphere of political and social philosophy.”

Turning the pages to see who this most clear and vigorous German might be, readers glanced past such items as a “Grand Temperance Rally in the 13th Ward"; a Philadelphia story headlined “Cruelty of a Landlord—Brutality of a Husband”: a Boston campaign telegram announcing a Whig demonstration “in favor of Daniel Webster for President.” Then they reached a long article entitled “Revolution and Counter-Revolution,” over the by-line, Karl Marx.

“The first act of the revolutionary drama on the Continent of Europe has closed,” it began upon a somber organ tone: “The ‘powers that were’ before the hurricane of 1848, are again the ‘powers that be.’” But, contributor Marx went on, swelling to his theme, the second act of the movement was soon to come, and the interval before the storm was a good time to study the “general social state … of the convulsed nations” that led inevitably to such upheavals.

He went on to speak of “bourgeoisie” and “proletariat”—strange new words to a readership absorbed at the moment with the Whig state convention, the late gale off Nova Scotia and with editor Greeley’s strictures against Tammany and Locofocoism. “The man goes deep—very deep for me,” remarked one of Greeley’s closest friends, editor Beman Brockway of upstate Watertown, New York. “Who is he?”

Karl Marx, a native of the Rhineland, had been for a short time the editor of a leftist agitational newspaper in Cologne until the Prussian police closed it down and drove him out. At thirty, exiled in Paris, he had composed as his own extremist contribution to the uprisings of 1848 an obscure tract called the Communist Manifesto. At least at this moment it was still obscure, having been overtaken by events and forgotten in the general tide of reaction

The following week Karl Marx was in the Tribune again, continuing his study of the making of revolutions. And again the week after that. “It may perhaps give you pleasure to know,” managing editor Dana wrote him as his series of pieces on the late events in Germany went on, “that they are read with satisfaction by a considerable number of persons and are widely reproduced.” Whatever his views might be, evidently the man could write. Next he branched out and wrote for Greeley and Dana on current political developments in England, France, Spain, the Middle East, the Orient—the whole world, in fact, as seen from his Soho garret. News reports, foreign press summaries, polemics, and prophecies poured from his desk in a continuous, intermixed flow, sometimes weekly, often twice-weekly, to catch the next fast packet to New York and so to earn from Greeley five dollars per installment.

This singular collaboration continued for over ten years. During this period Europe’s extremest radical, proscribed by the Prussian police and watched over by its agents abroad as a potential assassin of kings, sent in well over 500 separate contributions to the great New York family newspaper dedicated to the support of Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, temperance, dietary reform, Going West, and, ultimately, Abraham Lincoln. Even at his low rate of pay—so low that his revolutionary friend and patron, Friedrich Engels, agreed with him that it was “the lousiest petty-bourgeois cheating”—what Marx earned from the Tribune during that decade constituted his chief means of support, apart from handouts from Engels. The organ of respectable American Whigs and of their successors, the new Republican party, sustained Karl Marx over the years when he was mapping out his crowning tract of overthrow, Das Kapital.

In fact, much of the material he gathered for Greeley, particularly on the impoverishment of the English working classes during the depression of the late 1850’s, went bodily into Das Kapital. So did portions of a particularly virulent satire he wrote for the Tribune on the Duchess of Sutherland, a lady who had taken the visit of Harriet Beecher Stowe to London as the occasion to stage a women’s meeting that dispatched a lofty message of sympathy to their “American sisters” in their cause of abolishing Negro slavery. Marx scornfully asked what business the Duchess of Sutherland had stepping forth as a champion

The Tribune was not only Marx’s meal ticket but his experimental outlet for agitation and ideas during the most creative period of his life. Had there been no Tribune sustaining him, there might possibly— who knows?—have been no Das Kapital. And had there been no Das Kapital, would there have been a Lenin and a Stalin as the master’s disciples? And without a Marxist Lenin and Stalin, in turn, would there have been…? We had best leave the question there. History sometimes moves in mysterious ways.

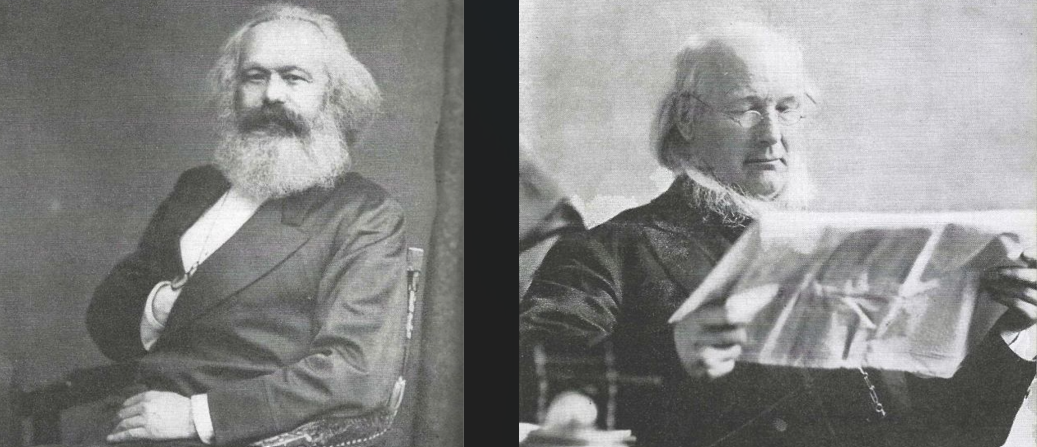

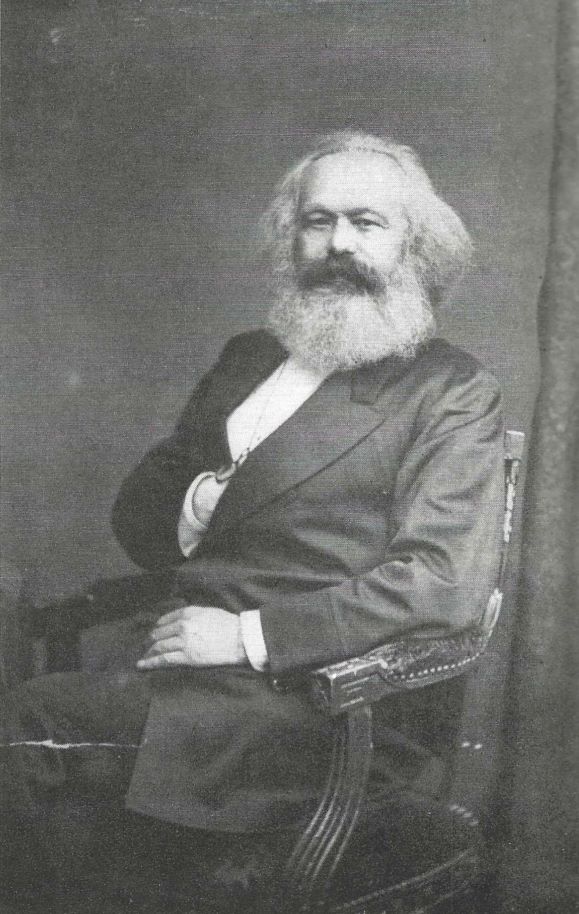

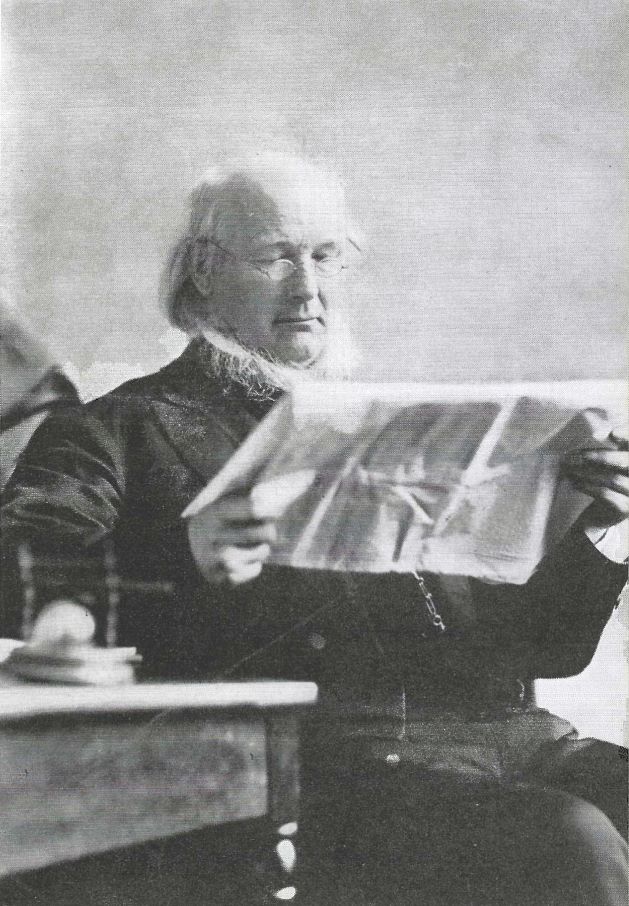

Few episodes in journalism seem more singular and unlikely than this association of the frowning ideologist of Soho on one hand and, on the other the moon-faced, owlish Vermont Yankee known affectionately to legions of readers in North and West as “Uncle Horace” as he traipsed around the country on the steamcars with his squeaky rural voice, his drooping spectacles, his carpetbag, and his broad-brimmed white hat. It is startling enough today that their careers should ever have become intertwined. What is even more odd in retrospect is the degree to which they did. Although Marx filed well over 500 pieces to the Tribune, just how many there were nobody knows, since many were “spiked,” killed and forgotten, while others were cut up and cannibalized, and still others were taken over bodily and printed without his by-line as leaders in the special precincts of Greeley’s own editorial page. Precisely which of Marx’s pieces were so used only a process of deduction and guesswork can tell, since no copies were kept. Today, scanning the Tribune’s files, one cannot be sure whether the voice one encounters thundering on its most famous page is that of the great Greeley himself or that of his rabid man in London, Herr Doktor Marx.

And the puzzle goes one step further. Even on those occasions when a Tribune contribution is clearly labeled as by Karl Marx, one cannot be sure that it really was written by Marx at all. Managing editor Dana, who conducted the office’s day-to-day dealings with its London correspondent, evidently believed that whatever Marx sold the Tribune as his own really was his own. But today we know better. From Marx’s immense correspondence with his acolyte, financial angel, and amanuensis, Friedrich Engels (still published for the most part only in the original German) we can discover something his American employers at the time never suspected, namely that much of what they bought as by “Karl Marx” was actually ghostwritten by the ever-helpful Engels.

Not one word of the opening article which the Tribune heralded as being

If readers were astonished at their Uncle Horace for bringing so alien a person as this Marx into their fold, they had only to remember that he had surprised them often before. In the ten years of its existence, his paper had espoused more varied causes and assembled around itself a more unconventional array of talents than any major daily had ever done before (and, one may safely add, than any has done since). It had come out for free homesteading and labor unions at a time when these were drastic new ideas. It had also backed socialist community experiments, the graham bread cult, pacifism, vegetarianism, and Mrs. Bloomer’s clothing reform. The Utopian Albert Brisbane had preached in its pages the virtues of his North American Phalanx, a communal colony set up according to the principles of the Frenchman Charles Fourier. The formidable, rhapsodic Margaret Fuller, whom Nathaniel Hawthorne had once called “the Transcendental heifer,” had preached feminism in it—and then moved right into Greeley’s own married home. The paper’s star performers ranged from Bayard Taylor, the romantic poet and world traveler whose profile made him look the part of an American Lord Byron, to George Ripley, the exuberant Unitarian minister who had broken away to found the cooperative retreat at Brook Farm where intellectuals carried on Socratic discourse and took in each other’s washing.

Greeley himself was always inquiring and imaginative, and with the priceless possession of an independent popular newspaper at his command he stood at the center of the turbulence as a barometer, a bellwether, a broker of new notions and ideas. Nothing was quite alien to him in the assorted stirrings of that era—not even the Fox sisters of Rochester, who had attracted much attention with their clairvoyant “spirit-rappings,” and whom he invited to his house for a séance along with the famed Swedish soprano, Jenny Lind, newly brought to this country as the protégée of his somewhat gamy yet still moralistic crony, Phineas T. Barnum.

For such a man as Greeley, then, not even Karl Marx was quite beyond the pale. What was meant by this

Up to a point, the apostles of change had a good case, he said in the Tribune. “We … who stand for a comprehensive Reform in the social relations of mankind impeach the present Order as defective and radically vicious in the following particulars…. It does not secure opportunity to labor, nor to acquire industrial skill and efficiency to those who need it most…. It dooms the most indigent class to pay for whatever of comforts and necessaries they may enjoy … at a higher rate than is exacted of the more affluent classes … [and] for the physical evils it inflicts, Society has barely two palliatives—Private Alms-giving and the Poorhouse….” Yet he did not want a class revolution, he insisted. He wanted to see co-operation and harmony. He looked forward to a reorganization of life amid the threatening weight of the factory system that would give each worker a share of the proceeds of the enterprise or else an opportunity to strike out on his own on free land from our national domain, where he could build his own enterprise.

Such ideas, far from seeming subversive, pulsed like wine through the veins of a young generation. One of those who had been swept up was a well-bred Harvard junior named Charles A. Dana. Young Dana, handsome, well-spoken, and idealistic, joined Ripley’s colony when it was set up at Brook Farm and lived there for five years, milking the cows, teaching other intellectuals’ children German and Greek, and waiting on tables to such distinguished visitors as Hawthorne, William Ellery Channing, Miss Fuller, and Greeley himself.

When Brook Farm burned down both Ripley and his young helper found berths on Greeley’s everhospitable Tribune. The year 1848 broke—a time of real revolution abroad as against the pastoral make-believe of Brook Farm at home. Young Dana, fired by the reports the first packet steamers

From this scene Dana sped on to Germany for more hopeful signs. There, in Cologne, he called on editor Karl Marx, then functioning during a brief lifting of the police ban as editor of the grubby Neue Rheinische Zeitung.

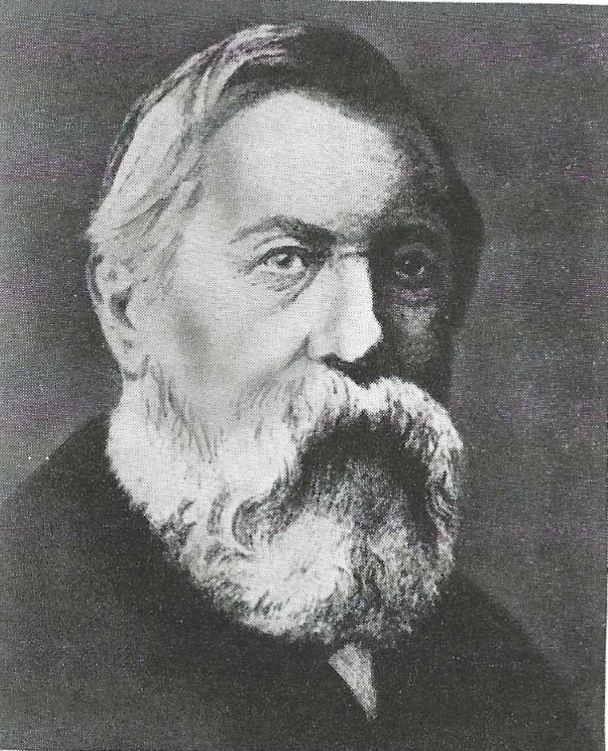

Just what young Dana of the Tribune and Marx of the Communist Manifesto said to each other that mid-summer day in Cologne is not of record. In later years, when he had graduated to become editor of the New York Sun in his own right and thereby a pillar of American society, Dana seems to have expunged all memory of that meeting from his mind. But it was there that the contact was made which led to Marx’s ten-year connection with the Tribune. And if Dana remained reticent, another caller on Marx that same summer has left a vivid impression of what the Cologne radical was then like. This other visitor was Carl Schurz, then himself a fledgling fellow-revolutionist of the Rhineland, and destined—like Dana himself—to a distinguished public career in the United States. Marx that summer, Carl Schurz recalled, “was a somewhat thickset man, with his broad forehead, his very black hair and beard and his dark sparkling eyes. I have never seen a man whose bearing was so provoking and intolerable. To no opinion which differed from his, he accorded the honor of even a condescending consideration. Everyone who contradicted him he treated with abject contempt…. I remember most distinctly the cutting disdain with which he pronounced the word ‘bourgeois.’”

Dana returned to the home office, aroused and enlarged by all he had seen abroad. Greeley, who had never been abroad himself, encouraged his bright young acquisition and made him managing editor. In this role, in 1851, he extended the Tribune’s invitation to Marx, then living in penury and exile at 28 Dean Street, Soho. Would he begin with a series on the late revolution in Germany? Marx jumped at it as a lifesaver. No English newspaper had wanted him as a contributor. For one thing, although he spoke a thickly accented English, he could not write the language. Yet this could be overcome by his getting in his friend and fellow exile, Friedrich Engels, to translate for him. Engels, the highly cultivated scion of a prosperous German textile family, was busy managing his father’s branch factory in Manchester and

Then Marx had a further thought. Why not have Engels write the whole series for him and thus leave him free to go on undisturbed with his studies for Das Kapital? So he wrote Engels imperiously, “You must, at this moment when I am entirely absorbed in political economy, come to my aid. Write a series of articles on Germany since 1848. Spirited and outspoken. These gentlemen [the Tribune editors] are very free and easy when it comes to foreign affairs." Soon acolyte Engels obliged, sending in his draft for Marx’s signature. “Mes remerciements pour ton article,” Marx acknowledged it, in that mixture of tongues he resorted to as a kind of exiled lingua franca; “Er … ist unverändert nach New York gesegelt. Du hast ganz den Ton für die Tribune getroffen.” ∗ [∗ "My thanks for your article. It … sailed off unchanged to New York. You have hit the tone for the Tribune precisely.”]

So, while Marx from his garret gave Engels the political line for his articles, saying he was too busy to do more than that, his faithful partner sat down after work at the factory to write what was required and then hurried downtown through Manchester’s midnight fogs to put his copy on the late express to London, where Marx would see it and pass it on across the sea. It was a demanding life for Engels, as he sometimes pointed out. Once he minuted to Marx, “Busy the whole day at the office; supper from seven to eight; then right to work, and sending all I could get done off now at 11:30.” Or “In spite of my greatest efforts, since I got your letter only this morning and it’s now eleven P.M., I haven’t yet finished the piece for Dana.” Marx, for his part, cashed the monthly payment drafts coming in from the Tribune.

Still Marx’s own life at that time was not one of ease. It resembled a nightmare. He was living and trying to do his thinking in a squalid two-room flat which he shared with his wife and as many as six children. Three died there while he went out begging from friends for food and medicine, and, in the case of one little girl whom the Marxes lost, the price of a coffin in which to bury her. When he finally did commence writing himself for Greeley in German in order to reduce the pressure on his friend, he sometimes found it impossible to go on. “My wife is sick,” he complained to Engels one day, “little Jenny is sick, Lenchen [the family’s factotum, also quartered in the same two rooms] has a sort of nerve fever. I couldn’t and can’t call the doctor, because I have no money for medicine. For eight to ten days I’ve fed the family on bread and potatoes, and it’s doubtful whether

Under such circumstances, the relationship to the Tribune of a man who was haughty and irascible to begin with, and stone-broke, bitter, and fearful of his family’s very survival besides, promised to be stormy. Marx constantly importuned his New York employers for more linage, better treatment of his copy, and, above all, more pay. When this was not forthcoming, he vented his spleen in scribblings to Engels in which he variously described the Tribune as Löschpapier (that blotter) or Das Lauseblatt (that lousy rag), its editors as Kerle and Burschen (those guys, those bums), Dana as Der Esel (that ass) and Greeley himsell as “ Dieser alte Esel with the face angelic.” The two German intellectuals consoled themselves by looking down their noses at the the mass-circulation Yankee daily for which they found themselves having to work. “One really needn’t put one’s self out lor this rag,” said Engels to Marx; “Barman struts about life-size in its columns, and its English is appalling.” And Marx in turn muttered to Engels, “It’s disgusting to be condemned to regard it as good fortune to be taken into the company of such a rag. To pound and grind bones and cook up soup out of them like paupers in the workhouse—that’s what the political work comes down to which we’re condemned to do there.”

Moreover, Marx disagreed with many of the Tribune ’s policies—although he avoided an open break, fearful of losing his meal ticket. One particular anathema to him was the idea of a protective tariff. Yet Greeley, whose dallyings with socialism had never interfered with his enthusiasm for American business enterprise, felt that protectionism was just the thing. When he heard this, Marx erupted darkly to Engels, “Das alles ist very ominous.”

Managing editor Dana had a difficult time with the impetuous pair in London. Most of the letters in which he answered Marx’s multilingual torrent of demands and protests have been lost. But Dana was a born diplomat, shrewd, worldly, a trifle sardonic, and his responses were always smooth. He addressed Marx gracefully “in the name of our friendship,” but avoided paying him the triple rate Marx had asked for, and eventually also cut down his space. Marx stormed but went on writing for the Tribune, which at least let him say what he wanted to say. “Mr. Marx has indeed opinions of his own, with some of which we are far from agreeing,” an editorial note in the paper remarked; “but those who do not read his letters neglect one of the most instructive sources of information on the great questions of European politics.”

For, in spite of all their letting off steam to one another about the “lousiness” of the Yankeeblatt the partners Marx and Engels finally settled down together to do an extraordinary journalistic job for it. In a day before the coming of the transatlantic cable, and when Europe’s own overland telegraph lines were still too sparse and costly to carry more than fragmentary press reports, England was the world’s great communications center by reason of its unrivaled sea traffic in every direction. Marx and Engels were keenly aware of this and set themselves up as a sort of central agency amassing world news and intelligence for their American client—with their own slant, of course. With Teutonic diligence they dredged up from diplomatic dispatches, statistical abstracts, government files, the British Museum, gossip, and newspapers in half a dozen languages gathered from Copenhagen to Calcutta, a mass of information on going topics such as had never reached an American newspaper before.

In 1853 the eyes of Europe turned apprehensively toward the growing crisis between the Western powers and Russia over the control of weak but strategic Turkey—a contest that soon led to the Crimean War. Marx and Engels provided their American readers with a background series that discussed the ethnic make-up of the area, reviewed its diplomatic history as far back as the treaty of 1393 between the Sublime Porte and Walachia, characterized all its chief personalities, and estimated down to battalion strengths the military forces and capabilities of the contenders. Some of this made for dry reading, but Marx had a way of breaking through into language of a vigor any American could understand. He poured vitriol on the Western rulers trying to maintain decadent Turkey as their tool:

“Now, when the shortsightedness of the ruling pygmies prides itself on having successfully freed Europe from the dangers of anarchy and revolution, up starts again the everlasting topic, ‘What shall we do with Turkey?’ Turkey is the living sore of European legitimacy. The impotency of legitimate, monarchial governments ever since the first French Revolution has resumed itself in the axiom, Keep up the status quo.... The status quo in Turkey! Why, you might as well try to keep up the present degree of putridity into which the carcass of a dead horse has passed at a given time, before the putridity is complete.”

Equally, he turned on tsarist Russia, in whose “good will” toward Turkey the Times of London was at the moment voicing hopeful confidence. “The good will of Russia toward Turkey!” he snorted. “Peter I proposed to raise himself on the ruins of Turkey…. Czar Nicholas, more moderate, only demands the exclusive Protectorate of Turkey. Mankind will not forget that Russia was the protector of Poland, the protector of the Crimea, the protector of Courland, Georgia, Mingrelia, the Circassian and Caucasian

On this score there was trouble again between Marx and Greeley. Greeley, a perennial twister of the British lion’s tail, was inclined to take sides with Russia’s aspirations. Marx was violently against all imperial ambitions in Europe. “The devil take the Tribune!” he exploded to comrade Engels. “It has simply got to come out against Pan-slavism. If not, we may have to break with the little sheet.” But he added quickly, “Yet that would be fatal.”

When Marx turned around again and let fly at the British government and social system, he spoke a language more pleasing to Greeley and his American constituents. The foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston, was “that brilliant boggler and loquacious humbug.” Lord John Russell was “that diminutive earth-man.” Gladstone was “a phrase-mongering charlatan.” And as for Queen Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert, “He has devoted his time partly to fattening pigs, to inventing ridiculous hats for the army, to planning model lodging-houses of a peculiarly transparent and uncomfortable kind, to the Hyde Park exhibition, and to amateur soldiery. He has been considered amiable and harmless, in point of intellect below the general average of human beings, a prolific father, and an obsequious husband.” By the time he wrote this, Karl Marx had clearly mastered English on his own and needed little further help from Engels.

But from under this coruscating surface there always emerged before the end of the article the same Marxian refrain. It was that of the inevitable approach of new and sweeping revolution. Marx saw it coming everywhere. One of his most scathing pieces, written with the atmosphere of a columnist’s exclusive, was a detailed forecast of the cynical maneuvers which he said the five Great Powers were about to stage over the Middle East. “But,” he wound up, “we must not forget that there is a sixth power in Europe, which at any given moment asserts its supremacy over the whole of the five so-called Great Powers, and makes them tremble, every one of them. That power is the Revolution. Long silent and retired, it is now again called to action…. From Manchester to Rome, from Paris to Warsaw to Perth, it is omnipresent, lifting up its head….”

And so on. Eventually the Tribune began to weary of Marx’s obiter dicta. For the next revolution in Europe showed no signs of coming. Instead of making for Marx’s barricades, the masses seemed intent simply on pursuing their own business. In 1855 editor Greeley traveled to Europe, a somewhat incongruous figure in his Yankee whiskers and duster. But he refrained from calling upon his chief correspondent and revolutionary expert in London, Karl Marx. So the two men, moving like tall ships on contrary courses in the narrow seas of

Perhaps Marx had laid on too thickly. Perhaps, while marshaling his massive batteries of facts and handing down his imperious conclusions, he had presumed too much on the hospitality of his readership. Or perhaps America, open-minded yet realistic and absorbed in the practicalities of its own fast-changing existence, had outgrown him. In any case he was not talking about unleashing the “divine life” in man, as the idealists around Greeley had done not so many years before. (Once a Tribune editor appended to a homily of Marx’s that was run as an editorial a windup sentence beginning, “God grant that—” which at once aroused Marx’s ire. He wasn’t asking God to grant anything.) Marx was calling for revolutionary wars and barricades. A war did come—but not the one Marx had projected. It was our own.

In 1857, a year when American minds were intent on our imminent crisis over the extension of slavery, Dana wrote Marx circumspectly on Greeley’s behalf to say that because of the current economic depression the Tribune found itself forced to reduce drastically all its foreign correspondence. “Diese Yankees sind doch verdammt lausige Kerle” (damned lousy bums), Marx burst out to Engels in his original German, charging that they now wanted to toss him aside like a squeezed lemon. But Dana, knowing Marx’s financial situation, came through with an offer of outside help. He himself was editing on the side a compilation to be called the New American Cyclopaedia. Wouldn’t Marx like to do a number of short sketches on historic personalities for it, at two dollars per printed page? Marx had no alternative but to accept. So the twin revolutionists sat down, grumbling as ever, to deliver hackwork biographies beginning under letter B with Barclay, Bernadotte, Berthier, Blücher, Bourrienne…

A trickle of further letters from Marx and Engels to the Tribune did continue, and Greeley and Dana used them when they found inclination or space. But the spacious enthusiasm of the days that had prompted the first of them had died away. It had been smothered partly by the rush of American events and partly by the realization that Marx, for all his efforts to stake a claim in the Tribune, did not, after all, speak our language. Dana, ever the diplomat, and appreciative of what Marx (alias Engels) had contributed over the years, notified him when the war between North and South broke out that while all other foreign correspondence had been suspended because of the emergency, he himself could continue contributing—although on a still more reduced basis. Marx, increasingly dubious of his American outlet, wrote for a while longer, only to learn that Dana himself, after what was reported to have been a falling-out with Greeley, had left the staff of the Tribune to become assistant secretary of war. Not long afterward, Marx’s own arrangement was canceled, too.

Now the frustrated

Marx was never again a correspondent for another newspaper. He had by now finished a great part of Das Kapital, for one thing, and henceforth went on to lead in organizing the Communist First International. Greeley, for his part, never once mentioned in his own memoirs the name of the most famous and controversial man who had ever worked for him.

Today all that remains of their episode together is a bundle of faded letters, a rash of multilingual expletives, and a file of published articles of whose authorship one can only rarely be quite sure. For Marx the collaboration was something less than a total success, for he never made Marxists of the subscribers to the New York Tribune. Did Greeley’s Tribune, in turn, with its hospitality and willingness to give free run to new ideas, have any effect upon Marx?

Perhaps it was too much to expect that any outside influence (particularly when money was involved) would have any effect on that somber man, pursued by his own demon of the absolute. Still, although Marx and Greeley found they had little in common save sheer journalistic energy and a gift for rhetoric, there were occasions when what either one of them said could well be put into the mouth of the other. Such an instance occurred on the last day of 1853, when many of the readers of the Tribune were as absorbed with the issues of East and West, of freedom and organization, as their descendants are today:

“Western Europe is feeble … because her governments feel they are outgrown and no longer believed by their people. The nations are beyond their rulers…. But there is new wine working in the old bottles. With a worthier and more equal social state, with the abolition of caste and privilege, with free political constitutions, unfettered industry, and emancipated thought, the people of the West will rise again to power and unity of purpose, while the Russian Colossus itself will be shattered by the progress of the masses and the explosive force of ideas.”

That passage was written by Karl Marx, not by Horace Greeley. You will not find it, though, in the official collected works of the father of Soviet communism.