Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1956 | Volume 7, Issue 3

Authors: Helen Augur

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1956 | Volume 7, Issue 3

“Our want of powder is inconceivable,” wrote Washington in the bitter early days of the Revolution. So too was our want of guns, supplies, and everything needed in a war against one of the major powers of the earth. Above all we needed an ally. And so the man who believed that there never was a good war or a bad peace, old Dr. Benjamin Franklin, a man laden with the world’s honors who might easily have pleaded age and weariness, set out for France in his seventy-first year to secure these necessities for his country.

The story of his amazing accomplishments, of his diplomatic feats, of his wizardry in supplying the Continental armies, of his struggles with envious fellow commissioners, scheming enemies, and vacillating friends—this is the burden of Helen Augur’s new book, The Secret War of Independence (Duell, Sloan and Pearce—Little, Brown). Miss Augur, one of many writers who have honored the great old man on his 250th anniversary this year, is the author of several other books, including Tall Ships to Cathay and biographies of Anne Hutchinson and John Ledyard. In making this special adaptation of her book for AMERICAN HERITAGE, she has re-created that less familiar but vital struggle behind the scenes which was necessary at Versailles before Cornwallis could march out, in defeat, at Yorktown while the drums beat for the birth of a new nation.

Late in October, 1776, Benjamin Franklin sailed for France to direct the foreign sector of the extraordinary war into which his young country had been plunged. It was an entirely new sort of war because the United States was a new sort of country, whose survival depended less on land fighting than on a complex of factors in which Franklin was deeply involved.

He had spent eighteen years in England as colonial agent and the last eighteen months at home in the Continental Congress. In that short interval he had seen his people take up arms for a desperate war, declare themselves a nation, and make the first cautious moves in foreign relations. As the American who best understood both sides of the Atlantic, Franklin had carried much of that burden, and for a long time to come would carry all the responsibility for getting maximum aid from the neutral powers without compromising the future of the new republic.

Franklin was now seventy, afflicted with gout, and wretchedly tired from his labors in Congress and its candle-burning committees. With British warships on the prowl the voyage was dangerous, but Franklin had brought his grandsons along. Little Benny Bache would be put in school to learn French, and Temple Franklin would act as his grandfather’s unpaid secretary. They were in the best possible hands; Captain Lambert Wickes was one of the few masters seasoned

Short as it was, the crossing was a godsend. With a fur cap on his unwigged gray head, Franklin took up his studies of the Gulf Stream where he had dropped them on his voyage home from England. He was free for a time to be the scientist, finding in nature a fidelity to laws beyond the reach of human meddling. Yet Franklin had a high opinion of the human race and lofty hopes for his particular segment of it.

A new nation had emerged, and in time each individual would realize his new identity. Early in 1774 Franklin had written from London to a friend at home that he wished Americans “might know what we are and what we have.” After much private groping and anguish he had discovered what he was: not a colonial American, but that new man, an American. Because the future could somehow work in him he had become the sort of man coming generations would repeat. He was the mutant of a new species.

A riving home just after Lexington, Franklin had found the leaders in Congress still struggling against their enforced propulsion towards independence. Congress had sent the King the Olive Branch Petition, which paralyzed war efforts for many months. It curtailed foreign trade at the moment when the country, which produced almost nothing useful in war, most needed to increase imports. Congress would not even sanction commerce with friendly powers because that was tantamount to declaring independence.

Franklin dealt with these suicidal moves in his usual oblique fashion. Instead of using direct pressure he used leverage. This kept him out of personal debates and increased his potential. With economic law as a lever he got Congress to open trade with the whole world, Great Britain excepted, three months before independence was ratified. The Declaration was passed with independence a hope on the far side of a hopeless-seeming war. But once these two great steps in the right direction were made, it was easy to push through resolutions for negotiating foreign alliances.

These three phases reveal an orderly progression in Franklin’s mind. His private period of turmoil and decision lay behind him, and he could think calmly of what must be done to make Jefferson’s great charter a reality. He was the unifying force of the Revolution, the one man who could understand and use effectively the complex elements which composed it. (One factor, the actual fighting on land, would make up the bulk of future histories. Thus torn from its context, the military side of the Revolution is implausible.)

On the land, if Washington finally got enough men and guns, he might wear down British troops far from their home base. But his eventual victory depended on two essentials which only Europe could

The thirteen colonies were in the nightmare situation of trying to fight the strongest power in the Western world almost barehanded. On Christmas Day Washington wrote Congress: “Our want of powder is inconceivable.” Three weeks later there was not a pound in his magazines. If General Howe had guessed that, he could have ended the war then and there.

By then Congress had set up two secret committees on both of which Franklin was extremely busy. The Secret Committee, dominated by the capable merchant Robert Morris, methodized the smuggling of war supplies from Europe, which had been going on for years. The Committee of Secret Correspondence, under Franklin, engaged agents abroad to explore the possibilities of foreign alliances. The colonies could not conclude treaties until they declared themselves a nation, and the necessity of getting military supplies and the support of a powerful fleet did a great deal to hasten independence.

Getting a fleet for Washington was high on Franklin’s agenda. The Continental Navy would never be able to take on the larger British units. America could fight only her own sort of war on the seas, and this had started before Lexington and would continue long after Yorktown. Hundreds of privateers were at their work of economic attrition, wearing down Britain’s strength by blows against her merchant shipping. But the early ratio of seven British merchantmen captured to one American lost was rapidly declining, and Britain’s patrol of the seaboard was making it difficult to maintain a supply line of military and civilian goods.

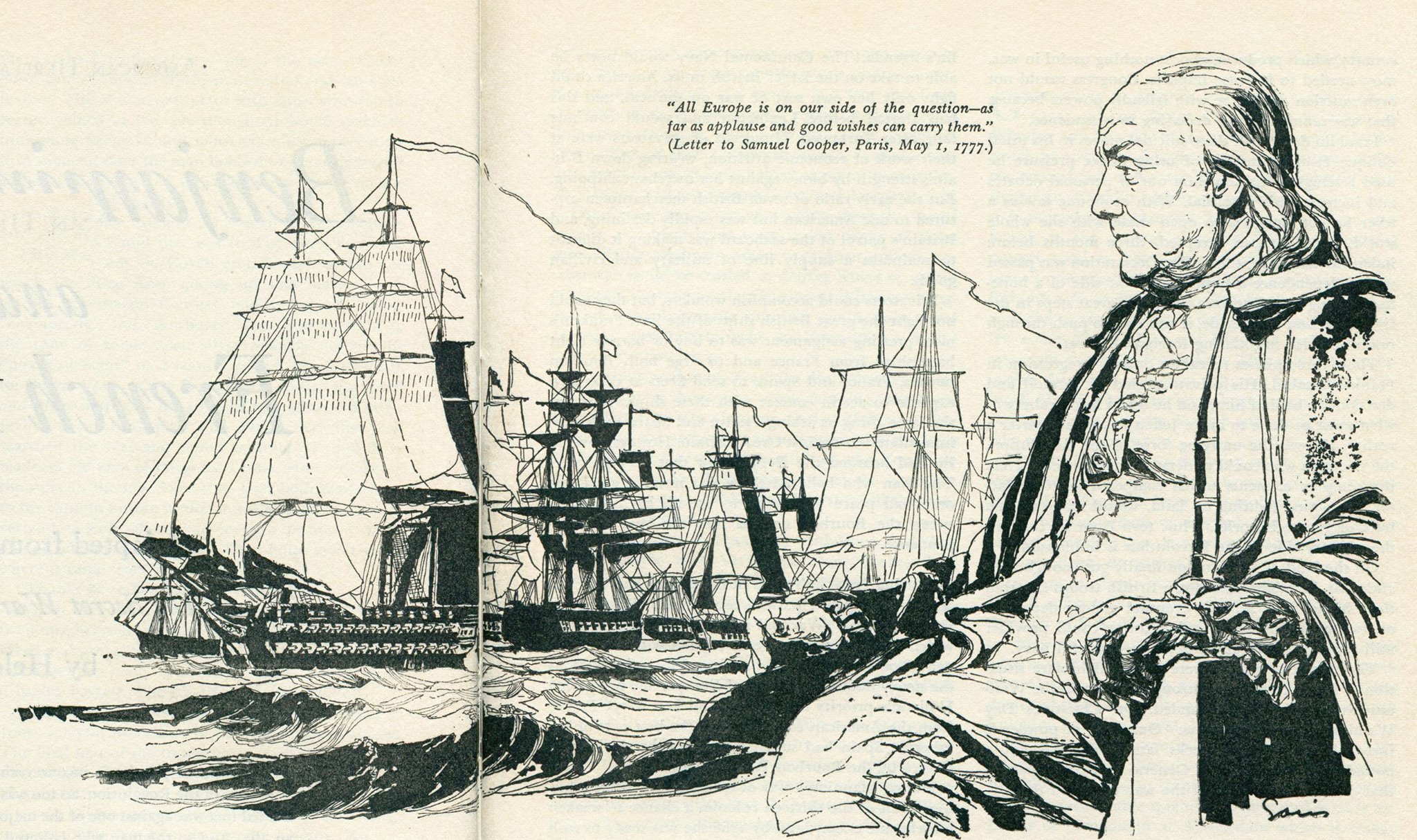

Privateers could accomplish wonders, but they could not fight the great British ships of the line. Franklin’s most pressing assignment was to buy or borrow eight battleships from France and to urge both Bourbon powers, France and Spain, to send fleets at their own expense to act in concert with these ships. This was the same thing as asking France and Spain to declare immediate war against Great Britain. However, Franklin had boarded the Reprisal for that very purpose. The man who believed there was never a good war or a bad peace was about to use all his powers to sweep the Bourbon nations into the War of Independence.

During Franklin’s years in London he had watched the old power pattern repeat itself. Britain won the Seven Years’ War and imposed the Peace of Paris which bred the next cycle of conflict with the Continental powers. They all hated and feared Britain as the newly dominant nation of Europe. She had stolen Holland’s priority on the seas and had swept France from the American continent and the best part of her fisheries. Spain had suffered less, but she was tied to France by the Bourbon Family Compact.

France, planning a war of revenge, saw in the growing revolt of the thirteen colonies a chance to weaken her chronic enemy, and by 1766 she was ready

During this period of watchful waiting, Franklin applied political pressure. One after the other his Whig friends rose in Parliament and warned that France might soon come out in support of the Americans. Since George III was violently against a war with the Bourbons these warnings disturbed him, but they did not change his fixed purpose to bully the colonies into obedience.

The historian Henri Doniol, who edited the secret French archives of the period, claimed that Franklin did more than coach the Whigs; that he in fact started an international gunrunning ring by quiet negotiations with certain arms manufacturers and exporters in England, Holland, and France. It is true that these countries, and to some extent Spain, had for some time been shipping out contraband for America, mostly through their Caribbean islands. It is also true that Franklin could have helped along such conspiratorial work without leaving a trace of his part of it.

The Doctor was adept at working through trusted friends, and his friends were legion. Some of them were British merchants; others were American sea captains who could be trusted to deliver letters or verbal messages to people on the Continent. Without changing his normal contacts Franklin could easily have guided a conspiracy to make the Revolution a reality instead of a lost cause.

According to Doniol, Franklin dealt through Sieur Montaudoin of Nantes, a great shipping merchant, and the savant Dr. Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg. Dubourg, said the archivist, amassed arms with the help of the brilliant new foreign minister, the Comte de Vergennes, who was determined to make the American rebellion a success; and Montaudoin shipped this contraband to America.

Both men were in Franklin’s confidence, and they worked closely with Vergennes. Sieur Montaudoin shared many interests with Franklin; both were members of the Royal Academy of Sciences, enthusiasts of the new physiocratic school, and Masons. But Montaudoin and all Nantes had begun to increase clandestine trade with the thirteen colonies about 1770, long before Franklin decided on his personal break with England.

As for Dr. Dubourg, this bookish man was an incongruous visitor at Versailles by June of 1776, by which time he had received Franklin’s appointment as the French agent of his Committee of Secret Correspondence. It was plain that Vergennes rather disliked him and gave every evidence that he was dealing with him only because he represented someone important. The arms of which Doniol speaks had long since been amassed, and it seems probable that Dubourg and Vergennes discussed other matters.

However, Franklin was a wizard at intrigue, and many secrets lie with him in the Christ Church burying ground. The fact that he was a genius, and a genius of such multiple gifts that he might easily inspire alarm or jealousy in others, had early taught him the art of using

Gunrunning to America was certainly going on in 1774, and no doubt Franklin knew about it. Whether this was one of the patriotic conspiracies for which he risked his life that year scarcely matters, for the contraband traffic would have gone merrily on if Benjamin Franklin had never existed.

A smuggling mechanism had long since been perfected, to the general salvation. All the colonizing powers tried to keep New World produce flowing home to the motherland. Americans, for instance, were forbidden to trade directly with foreign countries or with the foreign islands of the Caribbean, except in a few commodities which could be sold under cumbersome and expensive restrictions. This rule was so thoroughly disobeyed that great shipping houses like Willing & Morris of Philadelphia kept factors, or at least correspondents, all over Europe and the Caribbean to take care of their trade.

The Stamp Act riots were noisy on the land, but the seas were quiet and busy. Tobacco and rice, strictly reserved to England, were now rushed across the Atlantic to Amsterdam or Lorient and exchanged for cannon, powder, teas, and other goods which Americans could not do without.

In August, 1774, Sir Joseph Yorke, for years the British ambassador at The Hague, wrote his superior, the Earl of Suffolk: “As the contraband trade carried on between Holland and North America is so well known in England … I have not thought it necessary of late to trouble your Lordship with trifling details of ships sailing from Amsterdam for the British Colonies, laden with teas, linnens, etc.”

But now he had something serious to report: “My informations says that the Polly , Captain Benjamin Broadhurst, bound to Nantucket … has shipped on board a considerable quantity of gunpowder. It is the House of Crommelin at Amsterdam which is chiefly concerned in this trade with the Colonies, tho’ some others have their share.”

In later reports Sir Joseph drew such an alarming picture of Dutch gunrunning, especially to the Caribbean, that the British sent a Navy sloop and cutter to spend the winter at Texel Island near Amsterdam. Captain Pearson of the Speedwell had orders to follow any suspected American ship out to the open sea and there arrest her. (We must remember that all this was happening before Lexington.)

British firms had also been running munitions to the colonies, and continued to do so, despite orders-in-council. Finally the almost moribund Board of Trade and Plantations was given the assignment—which doubtless proved profitable—of issuing permits to merchants wishing to export warlike stores. The destinations given were usually French ports on the Channel, and the ostensible purpose was the sudden enormous need for arms in the French slave

By early 1775 the British embassy in France estimated that war supplies worth 32,000,000 livres (about $6,000,000) had been shipped from that kingdom to the colonies. The estimate means little, for the British were slow in discovering the tremendous scope of the activities abetted by Vergennes. He was such a master at dissimulation that he kept the British ambassador, Lord Stormont, convinced all through 1774 that nothing illicit was going on. There was merely enthusiasm for the American cause, Stormont reported to Whitehall, on the part of the “Wits, Philosophers and Coffee House Politicians who are all to a man warm Americans.”

The traffic which had started about 1770 was very large. American merchantmen picked up contraband all over Europe; the British, Dutch, and French sent some cargoes direct to the thirteen colonies, but far greater amounts to their islands in the Caribbean, to be picked up by American traders. The chief French ammunition dumps were Martinique and Cap François (now Cap Haitien) on Santo Domingo, known to seagoing Americans simply as “the Cape.” The Spanish shipped to New Orleans and Havana, and the British chose islands convenient to Washington’s chief arsenal, the Dutch island of St. Eustatia.

There is a distinct anomaly in the fact that even with captures from British transports Congress scraped together for Washington’s use in 1775 only about forty tons of gunpowder. Most of the supply was still down in the Caribbean, but the fact remains that there must have been more powder on the continent than the various colonies and the merchants were willing to release to Congress. No doubt the colonies hoarded local supplies for their own defense, and the merchants hoarded their stocks for higher prices. War profiteering was pandemic. Moreover, importers of cannon and powder had to arm their merchantmen, and if their merchantmen were transformed into privateers, as many were, they needed a large supply of ammunition.

The fact is that Congress had little authority over the colonies—it managed to adopt the Army, but the Continental Navy was a bitter joke. Long before it got into feeble action, eleven of the colonies had started their own navies, and several of them commissioned their own privateer fleets. Congress had little to do with America’s maritime war, which was a tremendous undertaking. It could not supply Washington gunpowder in 1775 nor cope with the enlarging task of war procurement.

The United States fought all the way through the war without a government. The country had no President and Cabinet, no executive departments, no constitution. It had only an overworked legislature trying to perform administrative functions. In this desperate situation a few individuals took over as heads of non-existent departments. Washington was the War Department, Robert Morris at various times was Treasury and Navy and always was Commerce, and Franklin was the Department of State. He had written his own instructions for Commissioner Franklin to carry out.

Franklin, bobbing a thermometer over the

Islanders and continentals had worked out a prototype of the free trade which was one of Franklin’s major objectives. Much of this trade was illicit, but it was based on realities and it bred a friendship between the West Indies and the mainlanders which was all-important to the Revolution. It is hard to see how the patriots could have started their war, or kept it going, without the help of the islanders.

The islet of St. Eustatia, an international free port in the northern Leewards, was a fountainhead of what Samuel Adams called the Unum Necessarium . Lying close to British, Danish, French, and Spanish islands, Statia, as she was known to her friends, had for generations offered European goods at bargain rates, and arms to any enemy of Britain. During the Revolution this tiny island was the clearinghouse for American trade with the Caribbean and Europe, including Britain. The warehouses lining her one street, a mile long, were crammed with munitions, ship’s stores, bolts of cloth; sacks of sugar and tobacco covered the very sands, and the roadstead was packed with merchantmen.

The greatest suppressed scandal of the war was the British trade with the enemy on Statia. Bermuda, which barely escaped becoming the fourteenth state, had a large merchant colony on the Dutch island, and there sold her American friends the thousand fine cedar sloops she built or refitted for them.

Franklin had a share in preserving the friendship between the mainland and Bermuda at a moment when it was severely strained. In the summer of 1775 Colonel Henry Tucker, whose clan dominated island affairs, came to Philadelphia in a state of worry and resentment. By September Congress’ lamentable trade embargo would include the West Indies, and no more mainland produce would be sent Bermuda, which meant a galloping famine. It also meant that mainland meat and fish would spoil for lack of salt. The only source for salt during the war was the Turks Islands beds at the tail of the Bahama chain, long a Bermudian monopoly.

When Colonel Tucker told Franklin and Morris that there was a respectable supply of gunpowder in the royal arsenal at St. George’s which could be abstracted in a midnight raid, a bargain was struck. Offered the bait of gunpowder, Congress swallowed the hook which Franklin had prayerfully included and ruled that any vessel bringing war supplies to the seaboard would be allowed to load up with produce. After

The powder was stolen; Bermuda was fed. For the rest of the war she ran salt to the mainland, refused to privateer against the Americans, and built for them her superb sloops. The Bahamas, too, acted as allies.

As for the French islands, the Cape developed into a prime source for munitions, and Martinique became an American privateer base before Franklin sailed. During the summer Congress became alarmed at the massing of French warships in the Caribbean and sent young William Bingham to find out whether this mobilization portended action against the United States. Captain Wickes, who had been one of the picked men of Morris’ trading fleet, was chosen for the voyage.

When they arrived at Martinique, the Americans were so cordially received that Bingham settled down as resident agent for Congress. It turned out that the French warships had been sent with orders to protect not only the islands of Louis XVI, but also any American vessels in the area. They might refit in the island ports, stock up their magazines, cruise the Caribbean, and bring their prizes in to St. Pierre for judgment in Mr. Bingham’s court of admiralty.

This was amazing enough; France had broken through the limits of her ostensible neutrality and was allowing Martinique to become a base of war against Britain. Franklin and Morris could hardly have believed Captain Wickes’ news on his return to Philadelphia if a courier had not come back from Europe at the same time with even more wonderful tidings. A certain Monsieur Hortalez, said the courier, was sending munitions worth £200,000 to the Cape, Martinique, and Statia, which American captains could obtain for Congress simply by saying “Hortalez” to the port commandant. There was no mention of payment.

It happened that Franklin and Morris were the only members of the Committee of Secret Correspondence in town when the courier arrived, and they resolved to keep the news to themselves. Anything known in Congress was apt to percolate to Whitehall. Franklin had already planned his mission to France, where he would be joined by his fellow commissioners, Silas Deane and Arthur Lee. Now he hurried his preparations, and Captain Wickes was ordered to make all speed to Nantes, and to avoid action if possible.

Nearing France, Dr. Franklin changed the captain’s orders. The Nantucket half of Franklin was always strong, and he longed to see how the captain and ship behaved in an engagement. Moreover, a certain project which he may have discussed with Morris and Wickes was developing in his mind, and he needed to find out how France would react if prizes were brought into Nantes.

Wickes took two small merchantmen which ran down their colors with alacrity. Franklin enjoyed the brief engagements. He wrote home that in the fighting there had been “good order and readiness … equal to anything of the kind in the best ships

Contrary winds kept the Reprisal from entering the Loire to make the port of Nantes. She anchored in Quiberon Bay with her prizes, and Franklin made a bone-racking journey overland by post chaise. He was hardly prepared for the booming activity in America’s behalf that he found in Nantes. Sailcloth and shoes, embroidered waistcoats and fusils, cannon and wig powder were crated and piled on the docks for shipment to the country that needed everything. There were sixty-odd American merchants established in Nantes, and when Franklin considered that all this activity was being repeated on a somewhat smaller scale in Bordeaux, Lorient, Le Havre, and Dunkirk, he felt that the Franco-American alliance was already a reality.

To the citizens of Nantes the alliance was not merely a commercial bond, but a blend of credos and enthusiasms which they shared with their friends overseas. Masonry was powerful in France and all-powerful in Nantes, and for perhaps a generation its exporters had been sending American brothers, along with bills of lading and business papers, sheaves of French Masonic literature in exchange for similar pamphlets from the colonies. The new physiocratic school had its followers on both sides of the Atlantic. And Franklin, Voltaire, and Rousseau were linked together as the presiding geniuses of the century. At the moment, Nantes was all Frankliniste .

The American was adulated, wined and dined. His friend Sieur Montaudoin bought a great Dutch ship and named it Benjamin Franklin . The Doctor, instead of staying with the Montaudoins, allowed himself to be captured by people he disliked. His discretion was fathomless, and he may purposely have avoided emphasizing his old friendship with the man who carried out some of the ministry’s most secret work for America. Franklin’s hosts were the merchants Pliarne and Penet, who had little standing in Nantes, but who may have been subsidized by Vergennes. At any rate, they had bobbed up in Philadelphia and obtained the first publicized arms contract between Congress and foreign shippers. Franklin soon warned Congress not to enlarge its connections with this questionable pair.

A growing fleet of American privateers had already brought prizes into the various French ports, and a system had been perfected for their disposal. When Wickes brought his captured brigantines to Nantes they were speedily bought by a French purchaser for less than half their value. A swarm of workmen then changed the “marks” of the vessels by slapping on new coats of paint, changing the figurehead, and such devices. The port records were similarly camouflaged.

The Reprisal was carrying a cargo of indigo worth £3,000 which was intended to pay the early expenses of the Paris mission. Pliarne and Penet undertook to sell the indigo, meanwhile giving Franklin a small cash advance—and that was about the last the mission got of the indigo money. Robert Morris’ alcoholic half brother Thomas had just been

Franklin’s arrival in Paris set off an extraordinary wave of public excitement that bordered on hysteria. In his plain dress, still wearing his comfortable fur cap, he was the natural man Rousseau had taught the French to revere, and a symbol of Utopia. France, wretchedly poor at the bottom of its society and jaded and apprehensive at the top, was rushing towards its own revolution, and the violent emotions which would ruin the French Revolution were tripped off in wild demonstrations of welcome.

Hoping to calm down the furor, Franklin appeared in public as little as possible. He closeted himself with Silas Deane, who had now been in France for six months on a dual mission for the two secret committees and had a tremendous budget of news. The two men had been on fairly close terms in Congress, where Deane had sat from the first day as a delegate from Connecticut. As a fellow commissioner, Deane’s prodigious energies and devotion to Franklin would help to pull them both through the stormy year ahead.

As far as brains and ability went, Deane belonged in the first rank of the men doing the hard immediate tasks of the Revolution. He understood not only the practical mechanics of business but the direction it would take after the war; his economic thinking was often bold and creative. He was a smaller copy of Robert Morris and aspired to become a great international merchant like his friend. At the same time he yearned to be a statesman like Franklin.

The trouble with Silas Deane was tragically simple: he was never quite sure who he was. People he loved and admired had far too much influence on him. A blacksmith’s son, he had worked his way through Yale and had started to practice law when he married the daughter of a great merchant family. That switched him to the Caribbean trade. His first wife soon died and he married the daughter of a great political family—and switched to politics. He did extremely well in these successive careers, and now at forty held a position of high honor.

On the surface Deane’s rapid rise might seem the result of clever opportunism in marrying and winning the friendship of the right people. But somehow, even when he acted in a cheap way, Silas Deane was not cheap. His emotional balance

However, Deane had already made a magnificent contribution to the Revolution in helping France to help America. He had a vital part in transforming the flow of war supplies from a too little, too late dribble into a steady stream which insured an American victory. Many of the vessels loading up in French ports with arms for Washington were the private ventures of merchants whom Deane had inspired with confidence. But his most important work was with the new firm of Hortalez & Company, which really meant the House of Bourbon.

Franklin had no doubt guessed, when the courier returned from Europe in September with news of tremendous shipments of arms by “Monsieur Hortalez,” that the real name of this mysterious friend was France. For diplomatic reasons, he always pretended a vast ignorance of Hortalez & Company—a feat like hiding an elephant in a hat.

The celebrated dramatist Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais now cast himself in his own best role, which he played without applause. If he had written the true story of his life as a drama no audience would have believed it. One of his parts was acting as confidential agent for the King, for his circumspection was as profound as Franklin’s. However, Beaumarchais put his whole soul into his character as friend of the American Revolution. For all his enjoyment of high life and high-level intrigue, he was a seismograph about social upheavals and an intellectual who understood their necessity.

During 1775, in London on a royal errand, he was in close touch with the American patriots. A year before the Declaration Beaumarchais wrote Vergennes that he was leaving for Flanders on a political mission, and that he had something tremendous to impart later. He was evidently buying arms and setting up a smuggling base in the Low Countries.

By September, 1775, the crusader was back in Versailles, and with Vergennes intensified the campaign to draw the King into their dangerous project of largescale aid to the colonies. Beaumarchais wrote masterly letters to Louis XVI, arguing that with timely secret help from France the Americans would win their war and clip Britain’s wings. Vergennes sent an agent, Achard de Bonvouloir, to Philadelphia to sound out Franklin about the prospects of a separation from England and a successful war. These prospects were bleak enough in December, 1775, but Franklin sent Bonvouloir back with such

France did not wait for the announcement of July Fourth. On May 2, 1776, Louis XVI signed documents committing France to action as a secret American ally, in violation of her treaties with Britain. He contributed a million livres to the colonies’ war chest and his uncle, Charles III of Spain, followed suit. On May 3 Vergennes wrote his royal master that he proposed to call in Sieur Montaudoin of Nantes and entrust him with forwarding funds and arms to America. But Beaumarchais had already outlined his plan for Hortalez & Company in a memoir to the King, and he persuaded Vergennes that this was the perfect device for concealing the Bourbon conspiracy against Britain.

The dramatist became a whirlwind of activity. Louis XVI, preparing for the war with England which Vergennes assured him was inevitable whether or not he aided the Americans, had ordered the Navy rebuilt and the Army re-equipped. This released a great stock of surplus arms for Hortalez to buy up cheaply. The bogus company functioned as a legitimate business house, paying cash for its purchases and keeping its connection with Versailles a secret even from the American leaders.

Athur Lee, who became Congress’ agent in London after Franklin’s departure, had been in conspiratorial relations with Beaumarchais during his visits to England. When the royal nod transmogrified Beaumarchais into Roderigue Hortalez, he wrote Lee over that signature, announcing the formation of his house and his intended shipments to the Cape, to be paid for by remittances of American tobacco.

What thus started as an acknowledged business arrangement was twisted by Arthur Lee into a fantasy which better suited his private purposes, all directed toward immortalizing Arthur Lee. He gave Franklin’s courier a verbal message: due to Mr. Lee’s unflagging labors with the French embassy in London, Versailles had been persuaded to send goods worth £200,000 (Hortalez had said 25,000) to the Caribbean as an outright gift. Later Lee developed this fantasy into a sinister engine of destruction against those he hated.

Franklin and Deane were at the top of that long list. Sitting together in Deane’s hotel while the crowds outside waited for a glimpse of their idol, the two men were already dreading the arrival of Arthur Lee as their colleague. Congress had appointed Jefferson as the third commissioner, but he had declined to serve because of his wife’s illness, and the Adams-Lee bloc in Congress rushed their man in as substitute.

For a complication of reasons the Massachusetts cousins, John and Samuel Adams, had formed a close alliance with the Virginia brothers, Richard Henry and Francis Lightfoot Lee. They were sure that the men who were shouldering the executive functions of a nonexistent Administration were in the wrong: Washington, Franklin, Morris, Deane, John Jay, and their hardheaded allies. John Adams once remarked that while Washington was to be respected as a private individual, in Congress “I feel myself to be superior

The two Lee brothers in Congress saw that their brothers in London were put in posts of influence. Arthur was installed in the place where he could counteract Deane and “that wicked old man,” as R. H. Lee called Franklin. William Lee was appointed joint commercial agent for France to checkmate Robert Morris’ brother. This move had been made after Franklin left Philadelphia, and the bad news would not reach Paris for months. But Franklin and Deane knew what to expect from Arthur Lee.

He was the dark personality of the family: a paranoid constantly haunted by the most fantastic suspicions of the people around him; a captious, hypercritical man who never married or made a simple friendship; a man with inflated notions of his own Tightness and genius who suffered tortures of jealousy of anybody above him. His jealousy of Franklin, which grew into a nightmare for Americans on two continents, had begun in 1770 when Massachusetts appointed Franklin its agent in England, and Lee his inactive deputy to replace him if he left England or if he died. Almost consciously Lee longed for that consummation.

Meanwhile Arthur Lee and his younger brother William joined the floating malcontents who supported the flamboyant John Wilkes and helped elect him lord mayor of London late in 1774. William Lee was rewarded with office as alderman of the city, a title which he did not relinquish until the war was almost over and he knew which side would win. Arthur Lee was rewarded by memories of turmoil, which he loved and which he was expert in creating.

His association with Hortalez was a stroke of luck. At last America would hear of the third Lee brother, hitherto a cipher, as its savior in Europe. When Deane arrived in Paris in the summer of 1776 Arthur Lee rushed over from London. But he was too late. Deane and Beaumarchais were already fast friends, working in harmony to load the Hortalez fleet with war supplies. Lee could not bear to lose Beaumarchais and tried to detach him from Deane. He only succeeded in quarreling with them both, and when he tried to see Vergennes, he was quite properly snubbed. All this was excruciating, since Lee had trumpeted in letters home that he had the ministry and Hortalez in his pocket. He went back to London in a fury.

Silas Deane was invaluable. He helped Beaumarchais buy and fit out eight ships, prudently scattered in various ports: the Amphitrite, Mercure, Flammand, Mère Bobie, Seine, Thérèse, Amelia , and Marie Catherine . Between them Beaumarchais and Deane amassed arms and every necessary article of clothing for an army of 30,000 men. By October Beaumarchais had spent the original 2,000,000 livres from the Bourbon kings, plus another million from France, and 2,600,000 livres

Delays which were not the fault of Deane and Beaumarchais held up most of the fleet for months after lading. But the Amphitrite and Mercure got away in time to reach Portsmouth by April, 1777, with supplies which at last turned the tide of war and made the crucial victory of Saratoga possible. The providence which was evidently favoring the American cause got the rest of the fleet safely to the mainland except the Seine , which the British captured after she had unloaded part of her cargo on Martinique.

Much of the maddening delay in dispatching the ships was caused by Vergennes. He had to fend off a break with England until France was ready for war. The Hortalez ships, scattered as they were at Marseilles, Bordeaux, Nantes, Le Havre, and Dunkirk, were still too conspicuous to be missed by the busy British spies. Lord Stormont, the British ambassador, had been sputtering at Vergennes for two years about the shipping of contraband from French ports, and now he raised such a storm that the minister had to forbid the sailing of one Hortalez vessel after the other. Then, when the diplomatic pressure eased, he would stealthily release them one at a time.

This cat and mouse game was only part of the new turn in French policy. Franklin found that the American stock had lately plunged to its lowest point. Washington’s defeat on Long Island and his retirement through the Jerseys made the Bourbon courts doubt if the war could succeed. There would soon be an unfavorable change in the Spanish ministry: Grimaldi, friendly to America, would be replaced as chief minister by the Count of Floridablanca, who feared that an America now independent would before long overrun Spanish possessions in the New World. His policy was to reconcile Britain and the United States; never, if he could help it, would Spain go to war on the American side. Even Vergennes was now lukewarm. He could not urge France into the war without Spanish support and without patriot victories to insure the survival of the young nation across the Atlantic.

Franklin immediately got to work at this dismal situation. As soon as Arthur Lee arrived from London the three commissioners wrote Vergennes announcing their appointment to negotiate a treaty of amity and commerce with France.

Vergennes promptly granted the requested interview. He already knew Deane, and wished not to know Arthur Lee, but he was consumed with curiosity about Franklin. The first diplomatic exchange between the United States and a foreign power was highly personal: Franklin and Vergennes sizing each other up.

Franklin knew that Vergennes, who for years had befriended America, would scuttle her the instant she ceased to serve his purpose. He knew that this purpose was the weakening of Britain rather than the emancipation of the United States. To Vergennes, Americans

Vergennes sensed that the benign old Doctor was ready to fence with naked steel, that he perfectly realized France was playing the old game of power rivalry, and that he would co-operate in the game—up to a point—to keep France as an ally. Discovering that point at which the common interests of France and the United States diverged would be a delicate task, and also an enjoyable one since he was matching wits with Franklin.

In a few swift parries Franklin suggested what his technique of dealing with the ministry would be. America needed French aid of every sort: ships, supplies, loans, to begin with. She was starting out as a beggar at the court of Versailles, and she would have to keep on begging until the war was over. By a supple turn of the wrist, Franklin transformed Franco-American relations. The United States, far from asking something for herself, was in reality advancing Bourbon interests and fighting their war. In order to make the war effective he reminded Vergennes of things Vergennes could do for the Bourbon cause: release the Hortalez ships, foster the American trade, and lend Congress money.

As a past master in the art of making the other man feel that he was acting solely for him, Vergennes recognized this basic technique in diplomacy. Moreover, he knew that Franklin was talking sense; if Washington was losing battles there were reasons for his setback which France could do a great deal to remedy. In this first interview the minister was lifted out of his discouragement by Franklin’s solid faith in the American destiny, and by his understanding of the whole European complex which made him able to suggest the right move at the right time rather than chimerical impossibilities.

If Vergennes had any doubts about Franklin’s grasp of Bourbon aims, they were resolved by the Doctor’s masterly letter of January 5. It began with the bold request that France sell the United States eight ships of the line, completely manned . England, Franklin said suavely, could hardly object to France sending the battleships with their crews, since Britain herself was borrowing or hiring troops from other states. But if she should declare war on France, “we conceive that by the united force of France, Spain, and America, she will lose all her possessions in the West Indies, much the greatest part of that commerce which has rendered her so opulent, and be reduced to that state of weakness and humiliation which she has, by her perfidy, her insolence, and her cruelty both in the east and the west, so justly merited.”

Vergennes himself could not have stated the Bourbon feelings

Franklin had already urged that France and Spain conclude treaties of amity and commerce with the United States, and his letter went farther, offering these powers a firm guarantee of their present possessions in the West Indies, plus any new islands they conquered in a war growing out of their aid to the United States.

And finally Franklin played his trump card, the possibility that America might be forced back into the British Empire “unless some powerful aid is given us or some strong diversion be made in our favor.” He knew that the Bourbon nightmare was the picture of Britain, reunited with her American colonies, sweeping Spain from the lower Mississippi and both Bourbon powers from the Caribbean. He was to evoke this nightmare more than once, but it never lost its effect.

A few days later Louis XVI made the United States a loan of 2,000,000 livres. The requested battleships were not forthcoming; it was explained that France needed every unit of her Navy for her own purposes, which of course meant her expected war with Britain. The royal loan was followed by an advance of a third million by the Farmers General of the French Revenue, who administered the government monopoly of tobacco and hoped for large shipments from Congress. It was a long time before this contract with the Farmers General could be satisfied, since few ships could now run the British blockade of the American seaboard. The French loan was a godsend. The commissioners drew on it for their expenses, for the purchase of war supplies, for building three frigates in Holland and France, and for keeping up the maritime war in European waters.

The situation at home was alarming. The British drive through the Jerseys threatened Philadelphia, and in December Congress evacuated to Baltimore, where it remained until February.

The currency had fallen to half its value. Naval affairs were stagnant; the privateers attracted all the able seamen. Shipping was at a premium; in the last year the price of vessels had tripled. The southern states were crammed with tobacco, which could not even be sent up along the coast because of the British cruisers on patrol. American morale was so low that only the immediate entrance of France into the war could put heart into the country.

Franklin resolved to break through any limitations put on his mission by Congress. Since France and Spain were not responding to the offer of a trade alliance, he raised his sights and proposed what amounted to a military one. On February i he urged that France enter her unavoidable war at once, and the next day gave Vergennes the personal pledge of the commissioners that if France entered the war the United States would not make a separate peace with Britain. Later Congress backed up this pledge and authorized “all tenders necessary” to get Bourbon help.

Communications with Congress were rapidly being snuffed out by the

At once, on March 17, the commissioners sent memoirs to the French and Spanish ministries urging a triple war against Britain and her ally Portugal. The joint conquest was proposed of Canada, the Floridas, and the British West Indies. If successful, France would get as her share half the Newfoundland fishery and all the sugar islands; Spain would be enriched by Portugal and the Floridas, and the United States would gain Canada, Bermuda, and the Bahamas. No peace would be made except by the general consent.

The memoir to Vergennes asked for a French loan of £2,000,000 (which Congress had hopefully requested) . If France refused armed intervention, the Americans prayed “the wise king’s advice,” whether to try to get help from some other power, “or to make offers of peace to Britain on condition of their Independency being acknowledged.”

Nothing came of these appeals, and meanwhile Franklin and Deane had been working at a highly secret project which might prove more effective in precipitating a Franco-British war. This required certain arrangements in the ports of France.

With the appointment of the mission to France the affairs of the two secret committees were theoretically unscrambled; the commissioners were to take charge of foreign relations, and young Tom Morris of commercial matters. Soon the old names were changed to the Committee of Foreign Affairs and the Commercial Committee to make this distinction clear. In France, however, this separation of function was impossible. Deane was up to his neck in business affairs and was essential to their success, for Tom Morris was clearly unfit to carry out any operation but commandeering cargoes from Congress to finance his endless debauch. The commissioners had written privately to Robert Morris that his brother must be removed, but their letters were not received for months.

By a natural process the activities of the mission were divided. Franklin took charge of diplomatic duties, Arthur Lee undertook missions to Spain and Prussia which happily kept him out of Paris at a crucial period, and Deane continued his commercial activities. Since the previous summer he had had the invaluable help of an unpaid deputy, William Carmichael. This wealthy and devoted young Marylander had been educated in England and was qualified for diplomatic assignments. But he was quite happy to spend the year of 1777 in the humbler role of itinerant trouble shooter in the French ports. For one thing, he worshiped Franklin and wanted to be useful to him; for another, he enjoyed hobnobbing with the rough sea captains he was assigned to help. It was Carmichael who

Since Nantes was the key port for American purposes, Franklin made a personal sacrifice and sent his grandnephew Jonathan Williams there as the special agent for the commissioners. Williams, now 27, had been trained in the Caribbean trade; he spoke French and was capable of dealing with accounts, which always baffled his granduncle. He was a young man of complete integrity and far from ordinary gifts, whom Franklin could well have used in Paris. But he was needed more in Nantes.

Franklin’s household, the unofficial American embassy, was never lonely, even when Benny was sent off to school. In March the Doctor was given a charming house at Passy on the grounds of the Hôtel Valentinois, which belonged to the merchant prince Donatien le Rey de Chaumont. The merchant was the intendant for supplying clothing for the French Army—and of late the American Army, for he had given Beaumarchais a million livres’ worth of clothing on credit.

Deane was in and out of the Passy house, keeping his hotel quarters for business and the entertaining of transient sea captains and a horde of friends. Temple Franklin was only seventeen, but he was working out well as his grandfather’s personal secretary, patiently making several copies of important papers to be sent on different ships bound for home in the hope that at least one copy would arrive safely. The Passy household was complete when the wise and enchanting Edward Bancroft arrived to act as general secretary of the mission.

Dr. Bancroft was an old friend of Franklin’s from his London days. Born in Massachusetts in 1744, Bancroft was just of age when he settled in London, but he was already a notable scientist and writer. He had spent years in Surinam and was an expert on tropical plants; he had written a natural history of Guiana and perfected new vegetable dyes for cloth. A member of the Royal College of Physicians, in 1773 he was elected to the Royal Society under the sponsorship of Franklin, the astronomer royal, and the king’s physician. Bancroft belonged to the American patriot group in London and wrote able papers defending the cause of the thirteen colonies.

When Deane left Philadelphia on his mission to France, Franklin suggested that Edward Bancroft would be a useful consultant on European affairs, and so it proved. He spent much of the latter half of 1776 in Paris as mentor to the inexperienced American, and the close friendship thus begun lasted as long as Deane lived. At Passy Bancroft was a loved and trusted figure, and Vergennes so admired him that after the war he sent Bancroft on a highly confidential mission to Ireland.

Sixty years after his death the incredible truth came out. Edward Bancroft had been in British pay since 1772. He was the “Edward Edwards” of the secret service, the master spy of the century. He was never suspected

As a weapon of war the British secret service was remarkably effective. It was run, personally and in great detail, by George III himself, who spent hours reading the reports of agents scattered over America, the West Indies, and Europe. The King was tireless, and only the quirks and massive stubbornness which were part of his psychosis would now and then hamper the working of his great information machine. He would not believe reports which meant bad news for England, or fully credit those which came from spies whose personal lives this virtuous burgher disapproved.

Lord North relayed the meticulous royal commands to the secret service, whose active head during the war was William Eden, a genius at directing espionage. His key man for American contacts was Paul Wentworth of New Hampshire, who before the war had been the London agent for that colony and after the war was elected a trustee of Dartmouth College, to which he had presented scientific apparatus. In the interval, quite unsuspected by his compatriots, he did high-level work for Eden.

Wentworth recruited Bancroft into the service and supervised his work in Paris closely, never quite sure of his loyalty to England. George III was uneasy about both Americans because they gambled wildly in stocks and kept mistresses. However, when Franklin arrived in Paris, Bancroft was in an ideal position to watch the King’s most dangerous enemy, and he made a good bargain with the secret service. He had a large family and expensive tastes, and needed and loved money. His contract with Wentworth gave him £500 down, the same amount as yearly salary, and a life pension.

In mortal terror of discovery, Bancroft was always called “Edwards” or some other cover name in the secret files, and even in private conferences with Wentworth and Lord Stormont. Since Wentworth often slipped across to Paris, much of Bancroft’s information could be delivered verbally, but he made a weekly report in writing.

These reports were written in invisible ink between the lines of love letters addressed to “Mr. Richardson” (Bancroft’s tiny, curiously contorted script was almost feminine). A box tree on the south terrace of the Tuileries Gardens had a convenient hollow under the trunk, and into this hole a bottle containing the gallant letter was let down by a string. Every Tuesday evening an agent of Stormont would pick up the letter and leave another with new instructions. The British were methodical.

In his contract Bancroft agreed to a long list of particulars. He was to steal all original papers possible from the commissioners, and copy others. He must gather exhaustive information on the mission’s dealings with Congress, with Versailles, with merchants shipping out contraband. Bancroft was to report on the movements of American privateers and trading vessels in European waters, and relations between the West Indies and continental America. Anything he could learn about the mission’s

The British had many other secret agents in France, and other avenues of information. Anthony Todd, secretary of the General Post Office, read Franklin’s letters to people in England. Moreover, every port in Europe was under the surveillance of the British Admiralty’s intelligence service, directed from Rotterdam by Madame Marguerite Wolters, widow of the former chief.

But Bancroft was in the most strategic position of any informer, and his conduct at Passy was mysterious. Franklin was a shrewd judge of men, and his unclouded confidence in Bancroft needs some extraordinary explanation. Bancroft was a supreme spy, but he preserved a curious code of his own, almost a code of honor, about what he would or would not do. He often held back information or distorted it, and Wentworth sensed this and by summer made him take an oath before he delivered an oral report. It is significant that while the Americans and French trusted Bancroft implicitly, the British were always suspicious of him, had his letters opened at the post office, and watched his movements.

While a gifted and expert secret agent can develop a second personality which keeps him from making slips, in Bancroft’s case this doubling of self may have reflected a profound split in the psyche. His affection for Franklin and Deane had the ring of sincerity, and years later, when Deane was of no possible use to him, he was still the devoted friend. Perhaps the greater part of Edward Bancroft was truly American. His contacts with his British employers revealed a quite different side, deformed by cupidity and fear.

Franklin faced the critical year of 1777 with the knowledge that the British fleet would pound American hopes to nothing unless France and Britain began their ordained war. France had 26 battleships ready, and by spring Spain would have thirty. Franklin looked upon these fleets with the lust of a patriot whose country was in mortal danger for lack of their support.

Plainly neither side wanted to start hostilities, and they had perfected a system for avoiding a rupture. Whenever Stormont got good evidence that France was shipping contraband to America or admitting American prizes to her ports, he drove to Versailles to make a formal protest. Vergennes would promise to investigate the matter, which meant that Stormont had lost a point. In the matter of the Hortalez ships, it was Vergennes who had yielded. By this process of elastic diplomacy the amenities were preserved while both sides gained time for war preparations and spared their exchequers the drain of active hostilities.

In short, England and the Bourbons had tacitly agreed that their war might be postponed indefinitely—and while they dallied, physical danger and sickening of hope were paralyzing America. Too much depended on Franklin. Congress demanded impossibilities of him: a huge loan which France could not afford, French battleships and seamen, and the prompt entrance of the Bourbons into the

However, he had proved to himself more than once that prodigies could result from careful planning and unstinted effort. Whatever disaster happened in 1777, he wanted to build a friendship between the French and American peoples which would last for many generations, and he calmly laid the foundations of that friendship in his own daily associations. His widening circle of intimates included people of great influence: Masons, scientists and scholars, men and women of the aristocracy. No man of his century could approach Franklin as a subtle and effective propagandist.

This long-range program was necessary, but it did not change the fact that the lumbering and inefficient British war machine had at last got itself oiled and repaired for a heavy assault upon the United States. Franklin had already done his utmost with the ministry, and there was nothing left but a new experiment—what would much later be called psychological warfare. In order to bring the reluctant enemies to blows he had to influence chiefly two men: George III, who was just as set against a French war as he was adamant in the American conflict, and Vergennes, the mentor of a young and inexperienced king.

Vergennes had patiently dissembled France’s violations of neutrality in one encounter after the other with Stormont. How long could he continue? There must be a breaking point somewhere in his patience. Only a frayed rope anchored the nations to peace, and Franklin believed that an implement lay ready to hand which would saw through the hawser.

Before he left Philadelphia Franklin had written with Morris certain instructions for Captain Wickes: he was to cruise against the British in their home waters, and bring his prizes into a French port. This was the germ of the deliberate policy Franklin and Deane pursued during 1777: to create such an open scandal about French connivance in American raids that it could not be effervesced in private conversations between Stormont and Vergennes. After the scheme had been put into effect they explained the mechanism to their committee: “For though the fitting out [of an American vessel in a French port] may be covered and concealed by various pretenses, so at least to be winked at by the Government here … yet the bringing in of prizes by a vessel so fitted out is so notorious an act, and so contrary to treaties, that if suffered must cause an immediate war.”

Knowing George III as he did, Franklin realized the importance of insulting him while all Europe looked on. The King was progressing from the swaddling clothes of a dominant mother to the strait jacket of his manic seizures, and even in his long periods of sanity his balance was precarious. He had corrupted his government from Lord North down in the hope of buying

On January 24 Wickes sailed out of Nantes with a French pilot and several French seamen aboard, strengthening the desired impression of collusion with Versailles. He made for the English Channel, where he took four small merchantmen, which he sent to Lorient under prize masters. Then he captured the King’s packet Swallow , running between Falmouth and Lisbon. Though the mail vessel was lightly armed she gave Wickes some trouble, and one of his seamen was killed and a lieutenant wounded.

England registered the expected sense of outrage; the whole country seethed with the news. When Stormont appeared at Versailles Vergennes assured him that the Reprisal and her prizes had been ordered to leave French waters within 24 hours. Nobody could find the prizes, which had been sold. As for the Reprisal , anchored at Lorient, she suddenly sprang a leak, and international usage allowed a ship in distress harbor privileges until she was fit to sail. Much later Wentworth revealed the trick: the night before the official inspection Wickes had pumped water into the hold. He now careened his ship and cleaned the hull at his leisure while the excitement died down.

Shortly after this, Parliament authorized British privateering. The move was long overdue, for the Americans had been making a brilliant success of their sea raids all over the Atlantic and the Caribbean. Many of them were now flocking to Europe, for the word had been passed of the hospitality of French and Spanish ports if the proper techniques of evasion were followed. Franklin wrote his Committee of Foreign Affairs of “the prodigious success of our armed ships and privateers.” London merchants had lost nearly £2,000,000 in their West Indies trade, and insurance had soared to 28 per cent, he boasted.

Soon Franklin and Deane had a group of young men busy in the various ports, helping merchantmen and privateers speed on their way, informing them of shifts in French regulations and dangerous areas patrolled by British warships, recruiting French seamen to fill out depleted ships’ companies, finding masters for ships and ships for masters. Arthur Lee, who would have ruined the secret project if he had been in Paris to interfere with it, was busy elsewhere. Deane, Carmichael, and Jonathan Williams were on the watch for daring and trustworthy captains for Admiral Franklin’s strategic naval force. They found the star of them all in Dunkirk.

Young Gustavus Conyngham of the landed Irish gentry had emigrated as a boy to Philadelphia where his relatives

Captain Conyngham had lost his ship on the last voyage, and was given command of the Surprise , a lugger newly bought for Congress. He came down to Passy to receive one of the captain’s commissions Franklin was empowered to issue, and then Carmichael took charge of him. Every step in preparing the lugger for a cruise was watched by the British in Dunkirk. During the last eighteen months Conyngham had been in and out of the port, always hull down before the British realized he had vanished, and this time they were determined to get him.

It was a fine moment for his debut. By April American privateers had taken so many British seamen prisoner that the British fleet was not half manned, and Stormont hinted to Vergennes that peace could not last much longer if France continued to arm the United States. Vergennes had answered, “Nous ne dé sirons pas la guerre, mais nous ne la craignons pas.” In sending on this encouraging word to Congress, Franklin added his own hopes about the Franco-British war: “When all are ready for it, a small matter may suddenly bring it on.”

The small matter was to be Conyngham’s capture of another British packet, this time the one plying to Holland. Somehow the wild Irishman, repeating the maneuver of the sound and sober Wickes, created an infinitely greater reaction. On the third day of May he seized the Prince of Orange and brought her into Dunkirk, along with a British brig picked up on the way. The sacred British mails were rushed down to Passy, and then the storm broke at Versailles.

Vergennes, facing a furious Stormont, knew he had been caught red-handed in a raid on the English mails by a ship fitted out in a French port. There was nothing to do but restore the packet and the brig to England and order the arrest of Conyngham and his crew. He made this gesture impressive by sending two sloops of war to Dunkirk to take the captain and his men and deliver them to the local jail.

The arrest did much to soothe British wrath. George III was delighted and directed Lord North to stress in Parliament this proof of France’s intention “to keep appearances.” The next step would be to force France to deliver Conyngham to Britain for hanging as a pirate. Vergennes kept him safe in jail, for the minister was co-operating with Franklin’s policy up to a dangerous point.

One result of the raid by

Franklin and Deane now wrote the committee urging action in every sea where British carried on commerce. They asked that frigates be sent over by August to cruise against England’s Baltic trade and attack the British Isles.

Still hopeful that Congress had ships to command, they spoke of raids on Greenland whalers and Hudson Bay fishing fleets, and urged that Navy ships convoy shipping in the Caribbean, since England would now send privateers and heavy units of her fleet there.

Carmichael wrote a strong-action letter to William Bingham on Martinique, mincing no words as to the policy being carried out in France: “I think your situation of singular consequence to bring on a war so necessary to assure our independence, and which the weak system of this court seems studiously to avoid. … As such is their miserable policy, it is our business to force on a war … for which purpose I see nothing so likely as fitting our privateers from the ports and islands of France. Here we are too near the sun, and the business is dangerous; with you it may be done more easily.”

He went on with suggestions for arming vessels in Martinique and manning them with French seamen, which must have amused Bingham, who was already busy at this very work. He and his friend the Marquis de Bouille, the new governor of Martinique, had a privateer fleet with American masters and French and Spanish crews which was making itself felt in the Caribbean. Bingham was in other privateering ventures with Robert Morris and had made St. Pierre a virtual American war base.

Late in May Captain Wickes made a cruise quite around Ireland in company with two other captains and captured eighteen small vessels. They sent eight of them to France and got back safely. George III now realized that the purpose behind the Wickes and Conyngham raids was to stir him up against France, which only increased his fury. Stormont was instructed to tell Vergennes that the “Rebels’” game was up.

Vergennes too recognized the subtle strategy behind the cruises, and he was coming to the decision that war could not be postponed much longer. To gain time, he placated Stormont by arresting the three Wickes vessels (which kept them safe from the British warships on patrol) and by promising that the new cutter being fitted for Conyngham would be sold. Stormont subsided; England needed time too.

Conyngham was still in the Dunkirk jail, the only safe place for him. His new cutter, the Revenge , had been bought by William

When Vergennes’s orders came through to sell the Revenge , nobody was alarmed. It meant only the familiar rite of “changing the property” on paper. Carmichael, who was still the liaison man between Passy and Dunkirk, found an obliging British subject as the ostensible purchaser of the Revenge , and while he was about it he sold the Surprise to a French “buyer” and sent her around to Nantes to join the privateer fleet.

Conyngham lusted for his fine new cutter, which mounted 14 six-pounders and 22 swivels, and would have a crew of more than a hundred American and French seamen. By late June the captain and his men were released from jail, and the Revenge was loaded with powder and arms. A week later she was halfway out of the harbor when a British sloop and cutter were sighted. Conyngham hastily sailed back to his berth and unloaded the powder. These British snoopers were the very ones who had quarantined the American powder runners in Amsterdam in 1774, and they came with orders to burn the Revenge if she sailed out. Besides, five British warships blockaded the harbor. It looked like a checkmate.

But in mid-July Conyngham took his unharmed cutter out to sea and anchored at a safe rendezvous. That night boats brought his cannon and powder and a number of French seamen, and the Dunkirk Pirate was on his way. A disguised British vessel at Dunkirk had alerted the warships, and as soon as the Revenge was in the open sea she was chased by several British frigates, sloops of war, and cutters. Conyngham shook them off and began the most spectacular cruise of the war.

He raided in the North Sea and the Baltic; he sailed around England and then around Ireland, everywhere taking prizes. He burned some and sent others to America, the West Indies, or whatever theater of war seemed to need their cargoes most. He terrorized the towns on the east coast of England and Scotland. He seemed to be everywhere at once, a nightmare figure. Finally, not daring to return to France, he made for Cap Ferrol in Spain.

One of Conyngham’s prizes was recaptured by the British, who took her into Yarmouth. The prize crew of five Americans and sixteen Frenchmen were put in prison, and the prize master was forced to confess that Conyngham had made other captures. The

Stormont then delivered to Vergennes threats only a step removed from war. If Conyngham was not punished, Stormont would resign, breaking off diplomatic relations with France. Moreover, orders would be given for British warships to seize the French fishing fleet daily expected from the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

Vergennes, who had confidently hoped to receive these protests under very different circumstances, was forced to buy a little more time at the expense of his American friends. He agreed to investigate the matter.

By the middle of July Vergennes had made up his mind to ask the King for armed intervention. He waited until the Revenge was safely out of Dunkirk, and then he and the commissioners exchanged letters, purely to clear the record, about the necessity of France abiding by her treaties, which meant no more violations by American privateers.

That formality over, Vergennes was ready for his great move. On July 23 he wrote a memoir to Louis XVI declaring that the moment had come when France must resolve “either to abandon America or to aid her courageously and effectively.” He urged a closer alliance to prevent a reunion of Britain and America. Secret aid was no longer sufficient, he argued, for the British claimed that the policy of the Bourbons was to destroy England by means of the Americans, and America by means of the British. Vergennes admitted that open assistance to the United States meant war, but war was in any case inevitable.

In the last months the King had relinquished his illusion that war could be avoided, and he approved his minister’s memoir the day it was presented. Because of the Family Compact, Spain would have to approve the alliance with America, and accordingly Vergennes’s memoir was sent to Madrid with its proposal for a triple offensive and defensive alliance.

Spain had been fighting Portugal in South America and had favored just such an alliance with the hope of getting Portugal as her share of the plunder. Now the picture had entirely changed, and Spain hoped to make peace with the new king on the Portuguese throne. Floridablanca’s policies prevailed; he wanted to keep the United States too weak to threaten Spanish possessions in America. Charles III refused the triple alliance. Louis XVI was helpless; he dared not begin the war without Spain.

This was a bitter blow to Vergennes and a calamity to the Americans. Franklin’s experiment had been a complete success in the laboratory sense; the sea raids had brought England and France to the verge of war. But he had not reckoned on the reversal of Spanish policy. Nor had Vergennes, who was extremely cool in his calculations. He had connived in the Conyngham raid in the confidence that

Now he must placate Stormont. He had come to the point where he must drop his perilous but always enjoyable collaboration with Franklin and play for France alone. He could not punish Conyngham, who was in parts unknown, so he had William Hodge arrested and sent to the Bastille.

Hodge was not released until the last of the fishing fleet was safely home in France. He soon went down to Spain, where Conyngham was taking fresh prizes.

Athur Lee’s mission to Spain had done nothing to warm her heart to America. The letter announcing his imminent arrival in Madrid was received with consternation. It was February, and the ominous shift in the ministry from the friendly Grimaldi to the hostile Floridablanca was taking place. The King was always anxious to avoid friction with England, and Lee’s visit would arouse her suspicions.

It happened that America’s greatest Spanish friend, the merchant Don Diego Gardoqui of Bilbao, was in Madrid at the moment, and he was called into consultation. He had high connections at the court, which did not at all disapprove his heavy shipments of arms to American merchants, and later he was appointed ambassador to the United States. Gardoqui proposed a sensible solution: he and the retiring foreign minister, Grimaldi, would arrange a secret rendezvous just across the border, and Lee would not enter Spain at all.

In the kindest of letters, Gardoqui explained the situation to the approaching envoy and suggested a meeting on the French side of the border. Since this ruined Arthur Lee’s flattering picture of himself as America’s first envoy to Madrid, he was enraged. He insisted on holding the conferences on Spanish soil at Vitoria; he wrote an ungracious memoir to Grimaldi and crossed the border.

Despite his own best efforts, Lee’s mission turned out to be a success. Grimaldi told him that the King was presenting the Americans stores of arms, clothing, and blankets which their ships could pick up at New Orleans and Havana. He was also making them a gift of 375,000 livres. For his part, Gardoqui promised to ship other stores on liberal credit.

Since Charles III had already contributed a million livres to Hortalez & Company, and allowed New Orleans to become an American privateer base, he may well have thought that he had done his share. After Lee’s visit he proffered no more aid and listened to Floridablanca.

Lee next stormed Prussia. A clever negotiator could have done much there, for Frederick the Great despised the British and the little German states that sold them mercenaries; he took a lively interest in the progress of the American war and was ready to expand Prussia’s trade with the Americans, which so far had been clandestine.

With great fanfare Lee proposed to make Prussia a second

As a result of Lee’s carelessness in leaving his portfolio in his room when he went out to dine, the commissioners had to abandon the building of a great frigate in Amsterdam, and she was sold to Louis XVI at cost. Their difficulties in shipping out supplies to America were also greatly increased, for Lee had set down everything he could learn without coding it.

He returned to Paris with his usual air of pompous impeccability, for his conscience was light. Some inner mechanism in the Lee genes transmuted whatever was wrong with the Lees into something much worse that was wrong with their enemies. He was delighted to find his brother William waiting for him in Paris. Due to the fantastic time lag in communications with Congress, Alderman Lee was about to take up his assignment as joint commercial agent for France ten months after Congress had canceled that assignment and appointed him envoy to Prussia and Austria.

Though he knew that affairs at Nantes were in a frightful state, William Lee lingered in Paris until August to confer with his brother about rearranging American foreign affairs to enhance the family glory. The first move was to eliminate Franklin and Deane by creating a scandal in Congress about their peculation of public funds. Much paper would be required for their letter campaign, and a spate of words would cover their omission of proofs. All that was needed was to add up the amount of money the mission had received, and then tell the Adams-Lee bloc in Congress that Franklin and Deane had stolen it.

William Lee opened the campaign against Deane in a letter to Francis Lightfoot Lee. “You can’t at this time,” he wrote, “be unacquainted with the faithless principles, the low, dirty intrigue, the selfish views, & the wicked arts of a certain race of Men, &, believe me, a full crop of these qualities you sent in the first instance from Philadelphia to Paris.”

Arthur Lee then followed with a letter to Samuel Adams which revealed his definite plan to supplant Franklin. The court of France, he wrote, “is the great wheel that moves them all” and he added that of all posts he preferred Paris for himself. On the same day he wrote Richard Henry Lee: “My idea of adapting characters and places is this: Dr. Franklin to Vienna, as the first, most respectable, and quiet; Mr. Deane to Holland; and the alderman [William] to

He went on to suggest how Franklin and Deane might be erased altogether. Once he was installed as sole envoy in Paris, “I should have it in my power to call those to account, through whose hands I know the public money has passed, and which will either never be accounted for, or misaccounted for, by connivance between those, who are to share in the public plunder. If this scheme can be executed, it will disconcert all the plans at one stroke, without an appearance of intention, and save both the public and me.”

Just a year after independence was declared the Americans lost Fort Ticonderoga to Burgoyne, and on September 26 Howe entered Philadelphia. Vergennes was so disheartened by the bad news which had arrived even before these disasters were known, and he so much dreaded a sudden declaration of war by Britain, that in August he formally closed the ports of France to American privateers and their prizes. Franklin and Deane co-operated with him by being very discreet about evading this prohibition, but the year which had begun so brilliantly in maritime operations was in the doldrums.

British spies were everywhere. Bancroft was still the mission confidant at Passy; certain Americans who sat at Deane’s dinner table reported on ship movements to the British secret service, and Captain Joseph Hynson, who happened to be Lambert Wickes’s stepbrother, stole an entire pouch of dispatches intended for Congress, which contained all the secret correspondence between the mission and the French ministry for the last eight months. This theft was not discovered until the pouch was opened in America and proved to contain nothing but the blank paper substituted by Hynson. The stench of treachery was in the air.

Franklin comforted himself by beginning his magnificent work for the prisoners at Forton and the Old Mill in England, masters and men of the Continental Navy and the privateer fleet who were classed as pirates by George III and who sickened and starved in his antiquated prisons. Through English friends Franklin raised funds to give the prisoners warm clothes and blankets, food, a chance to bathe and wash their clothes, and spending money for small comforts. With Deane and Carmichael, and all those shadowy young Americans who helped the great privateering drive of 1777, he organized an underground system for escapes.

A phenomenal number of men escaped Old Mill Prison at Plymouth; they scaled the walls, dug long tunnels under them, or bribed the guards to let them through the gates. Before they escaped they were furnished money and instructions about English allies who would get them across the Channel, and French merchants at the ports who would then take care of them. On his first escape from Old Mill in 1779, Conyngham tunneled out with 53 companions. Franklin labored incessantly to get prisoners exchanged in the