Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2008 | Volume 58, Issue 1

Authors: Elizabeth Brown Pryor

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2008 | Volume 58, Issue 1

One April afternoon in 1861, a proud man in his early 50s strode nervously across the portico of his home, too distracted to appreciate its sweeping view of the Potomac. He had an elegant military bearing and the dark looks of a stage star, but, on this day, his genial face was shadowed by worry. His unsettled demeanor surprised several onlookers, accustomed to his normally composed nature.

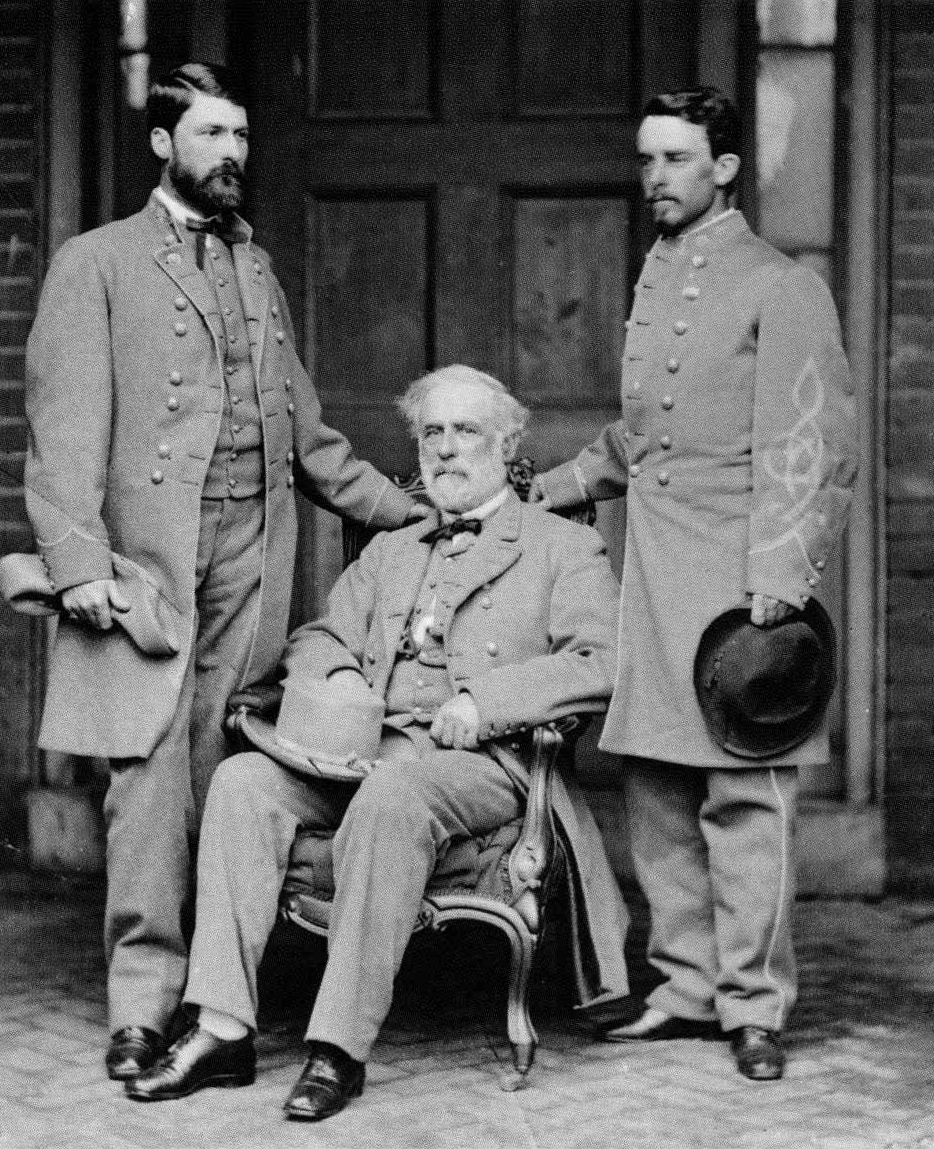

A family slave, Jim Parks, described his master pacing “backwa’d and fo’ward on de po’ch, steddyin’.” A young cousin puzzled as his relative circulated slowly through the garden, lost in uneasy reflection. The tension increased over the next two days: now, the troubled footsteps could be heard treading across the upstairs chambers, punctuated by the sounds of fervent prayer. As his family gathered below in apprehension, Colonel R.E. Lee of the U.S. Army agonized over both his own future and that of the nation.

This is an enormously charged moment, a scene worthy of Shakespeare. Few decisions would carry more consequence than Lee’s determination to join the secessionists as the Union split apart. In the months following this anguish, Lee would also begin a metamorphic journey, shedding long-held loyalties, his privacy—even his former identity. Once a respected, but little-known officer, he was now the object of public comment. Newspapers began calling him “Robert E. Lee”—a name neither he nor his family ever used. His appearance altered radically. By November 1861, the black curls and square chin were lost beneath a beard and rapidly whitening mane. His acquaintances later wrote that they were stunned by such marked changes in a man they thought they knew.

The true drama of the moment, however, lies in Lee’s own desperation. As his wife would attest, it was the “severest struggle of his life.” Yet part of the tradition surrounding Lee is that his decision to fight for Virginia was virtually foreordained. Historians have traditionally portrayed it as an inevitable historic moment—a “no-brainer” in the words of one contemporary writer. But a close examination of neglected private papers, including two tantalizing trunkfulls of long-forgotten family letters, shows not only that Lee suffered intensely as the nation was skidding into war, but that his personal battle was extremely complicated.

He was not a victim of fate; nor was he a captive of family expectations or rigid codes of conduct. Indeed, he

Born 200 years ago in Westmoreland County, Virginia, Robert Edward Lee was bred in households that supported a strong Union, capable of defending its principles as well as its territory. The son of Revolutionary War hero “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, Robert graduated from West Point in 1829 and two years later married Mary Anna Randolph Custis, the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington. Home for the couple and their seven children was Arlington, the Custis family seat, just across the river from Washington D.C. The army trained Lee to view his profession as a national responsibility and in his 35-year career he served all over the country—in frontier cities like St. Louis, fighting Indians on the Texas plains, or building eastern seaboard fortifications. Although he remained powerfully attached to his native state, in 1857 Lee told a brother-in-law that his patriotism encompassed “the whole country” and that its limits “contained no North, no South, no East no west, but embraced the broad Union, in all its might & strength, present & future.”

Nonetheless, the increasingly shrill tone of the abolitionists and the attitude of the North’s majority population worried Lee, as it did many Southerners. He also owned human property and believed that a master/slave relationship was the best that could be expected between the races. A multiracial society with egalitarian overtones was not just unattractive to Lee, it was unthinkable. Most Americans, including Abraham Lincoln, agreed.

Lee had specific reasons, however, to fear an uncontrolled black populace. In the late 1850s, while executor of the large Custis estate, he had faced a group of slaves who resisted his authority, possibly with the encouragement of local abolitionists. The slaves had been freed by his father-in-law, in a messy will. Recently discovered court records show that Lee aggravated the situation by trying to postpone the bondsmen’s liberation. Believing they were entitled to their freedom, and alarmed at the way Lee was breaking up their families by hiring the able-bodied far from Arlington, the slaves banded together and tried to overpower him physically, shouting that they were as free as he was. Angered by the slaves’ defiance, Lee resorted to increasingly harsh measures to maintain control.

of marines to quell a bloody insurrection masterminded by abolitionist John Brown. " data-entity-type="file" data-entity-uuid="2b083b64-823c-4534-9b12-43c9b920d35d" height="628" src="https://www.americanheritage.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/1b__Harper%27sFerry.jpg" width="920" loading="lazy">

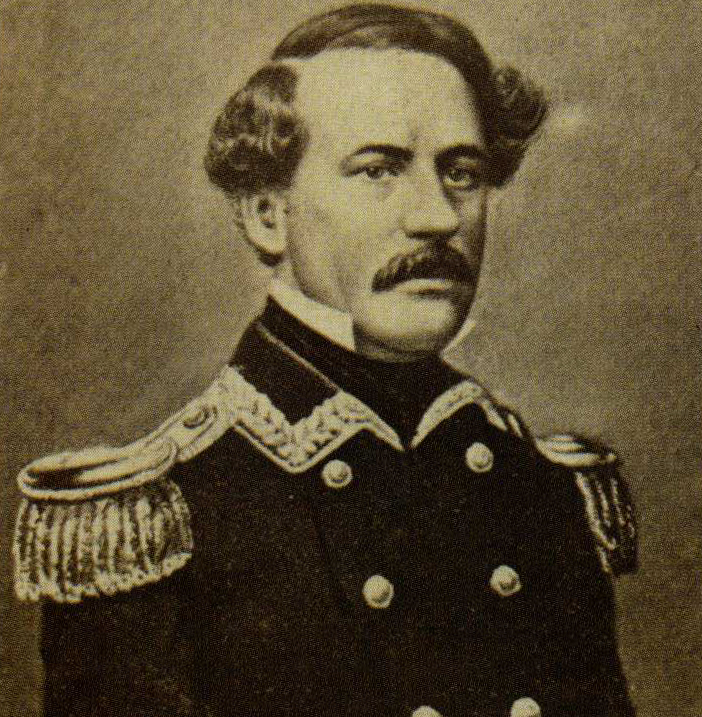

A few months later, Lee commanded the marines that captured abolitionist John Brown during his attempted insurrection at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. Though he directed a nearly flawless operation, the experience again chilled him. He was in the room when Brown uttered a bold warning of the cataclysm to come. “You may dispose of me very easily . . . ,” Brown said, “but this question is still to be settled—this negro question, I mean—the end of that is not yet.” The ordered world that Lee knew was disintegrating before his eyes.

His anxiety intensified a year later when Abraham Lincoln was elected president. Lee was in San Antonio at the time, chasing Mexican bandits. The mood was bad: the secessionists in the Lone Star State were gaining ground, and malaise among his colleagues was also growing. The regular army was a close-knit institution, which discouraged partisan sentiment or parochialism in its officers. At the same time, there was a good deal of sympathy for the South, and slavery was generally tolerated. But the divisive election of November 1860 forced military men to confront their competing allegiances to army, family, and nation.

Many officers were torn by conflicting passions, and stories from 1860-1861 throb with anguish. Albert Sidney Johnston wandered overland in a “desperate” state of mind, after being relieved of command by suspicious authorities in Washington. Virginian Joseph E. Johnston was escorted from the Secretary of War’s rooms in a state of collapse as he resigned his commission. Lee was shocked when local radicals demanded he, too, resign, and then insisted he turn over the army stores he controlled. He startled his colleagues by exploding with rage at the pressure to abandon his career, and later wept publicly when he heard that Texas had actually left the Union. One of the era’s ironies was Lee’s insistence that the secessionists would have to fight him to get federal property. Had they forced the issue, as they later did at Fort Sumter, the Civil War might have begun in Texas—with Colonel R.E. Lee defending the Union assets.

Lee nearly got his wish that Virginia stay with the Union when a vote for secession failed at the state convention.

Lee was jolted into reality by the fanatical actions surrounding him in Texas. Exasperated at both sides, he lambasted the “dictatorial” bearing of the South as much as the North’s aggression. He repeatedly expressed horror at the thought of dismantling the country, maintaining that disunion was “anarchy” and secession “nothing but revolution.” Yet, from the start, Lee knew his destiny was to follow the fortunes of Virginia. What he hoped was that the Old Dominion would stay with the Union, allowing him to uphold his twin loyalties to nation and state. “I am particularly anxious that Virginia should keep right,” he told his daughter Agnes, adding that since the state had been instrumental in shaping the Constitution, “so I would wish that she might be able to maintain it, to save the union.”

As the country became polarized, however, Lee’s words became convoluted expressions of his ambivalence. When he drove away from Texas, a fellow-officer called after him: “Colonel, do you intend to go South or remain North?” Lee stuck his head out of a covered wagon and replied, “I shall never bear arms against the United States—but it may be necessary for me to carry a musket in defence of my native State, Virginia, in which case I shall not prove recreant to my duty.” In another moment of supreme confliction Lee confusedly declared: “While I wish to do what is right, I am unwilling to do what is not, either at the bidding of the South or the North.”

Part of Lee’s dilemma was the clash between real and perceived obligations. He had sworn multiple times to maintain loyalty to the United States “against all enemies or opposers whatsoever.” Yet somehow he had the nagging sense that his first duty was to Virginia. It was a bond with place and patrimony; something perhaps more to do with the smell of lilacs in an old garden, or faces framed in candle shine, than with any patriotic credo. He told a friend he had been educated to believe his state should take precedence, but when his companion recalled the strong unionism of Lee’s father and brothers, asking “from whence was this education,” Lee only responded that he could not help feeling as he did. He may have genuinely believed that his father had followed Virginia’s lead, but this too was a mirage. In fact, the elder Lee had led the U.S. army against rebels during the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, the first challenge to federal authority. He had also eloquently defended a Constitution that began “We the People” rather than “We the States.” Harry Lee acknowledged Virginia as “his country,” but unequivocally stated that the nation’s happiness depended “entirely on maintaining our union” and that, “in point of right, no state can withdraw itself from the union.”

In 1861, Robert E. Lee argued that there was no justification for secession (though after the

Lee nearly got his wish that Virginia would remain with the Union. Though it had the largest slave population of any southern state, in the 1850s, Virginia’s economy had become increasingly diversified. With an influx of northern immigrants, the growth of railroads, and political reforms that were beginning to challenge the old seigniorial class, it had more in common with Maryland, which stayed in the Union, than with the Cotton States. There were some notably outspoken personalities in the Old Dominion, but overall, there was no great leap to embrace the risky policies of South Carolina. Before Lee returned from Texas on March 1, 1861, Virginia had already held a secession convention and the pro-South faction had failed to win the day.

On arrival in Washington, Lee found the capital nervously preparing for the Lincoln administration. In theory,

Lee had been recalled to sit on a board revising the army’s regulations, but he and others were aware that he was being considered for higher responsibility. Lincoln was starting to assemble his military machine, making appointments and reassigning troops. Lee’s capabilities—and his allegiance—were among those under discussion. An aide to Simon Cameron, the new secretary of war, recalled a meeting at which Cameron asked General Winfield Scott if he had confidence in Lee’s loyalty. “Entire confidence, sir,” was Scott’s typically booming reply. “He is true as steel, sir, true as steel!” A week later, on March 28, Lee received news that Lincoln had promoted him to full colonel of the 1st Regiment of Cavalry—a coveted position. Lee accepted, once more swearing allegiance to the Union.

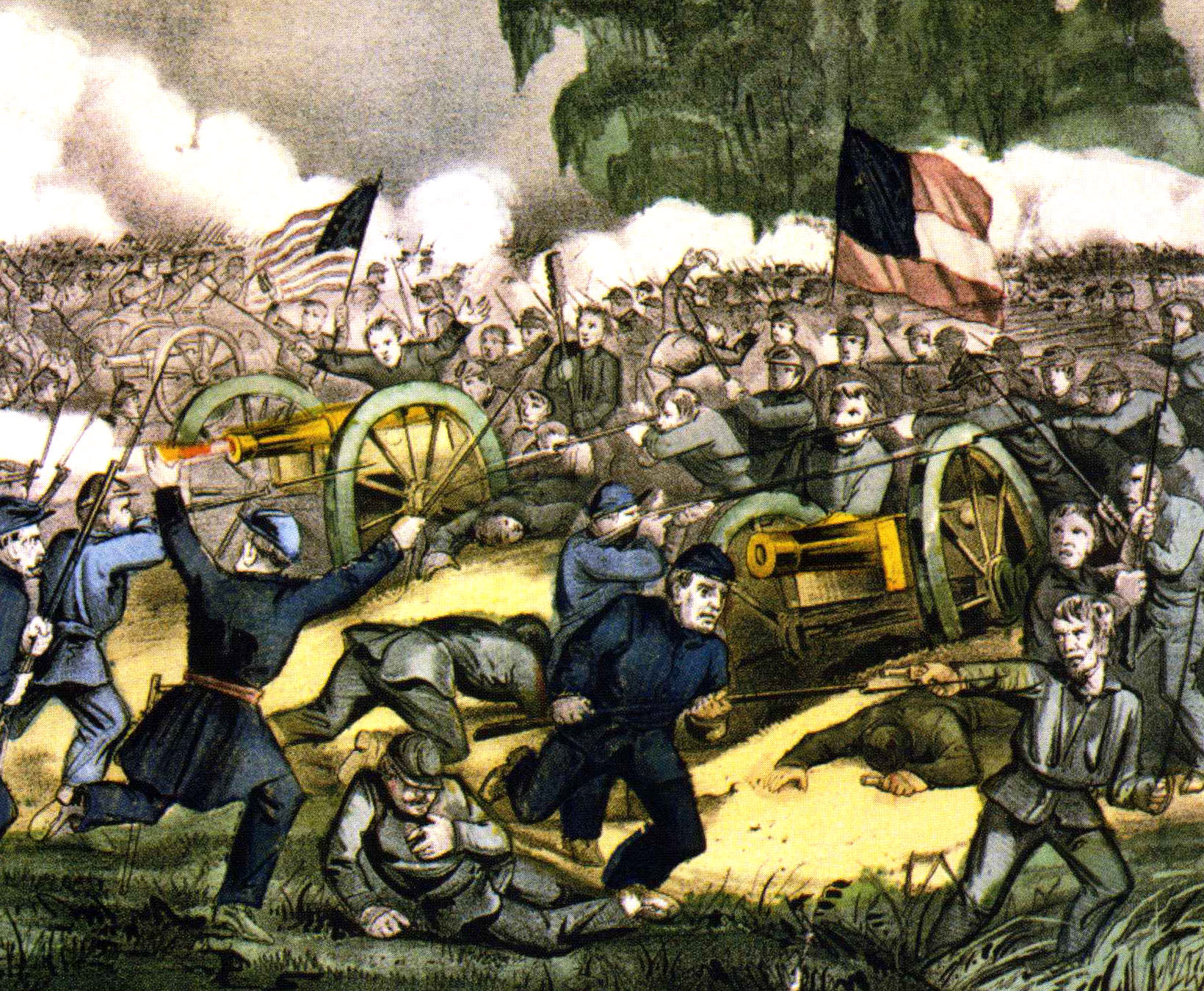

But, within days, Lee and the rest of the nation were caught up in events moving swiftly beyond anyone’s control. In early April, Lincoln made the difficult decision to

The two actions galvanized both sides: the North feared wholesale revolution, and Southerners believed Lincoln was preparing to invade their homes. The fury of the moment overturned the fragile peace crafted by Virginia moderates. Virginia Senator Robert M.T. Hunter waved away those who lamented the growing radicalization. “My dear lady,” he told a friend of the Lee’s, “you may place your little hand against Niagara with more certainty of staying the torrent than you can oppose this moment.” On April 17, the question was again put to the convention in Richmond. This time, they chose secession.

At Arlington, Lee learned with dismay of the decision. The verdict was not yet final—that would depend on a popular referendum scheduled for May 23—but few doubted the outcome. Heartsick, he apparently dined that night with his brother Smith Lee and their first cousin Phillips Lee, both U.S. naval officers. The navy men joked about the conflict, waging mock battles at the table, but Robert remained miserable and mute. Phil Lee thought that his cousin’s silence showed indecision, and hurried into the War Department the next morning, warning his superiors that they might lose him unless they acted quickly. One of Lincoln’s closes advisers, Francis Preston Blair, summoned Lee to his offices. Another message requested his presence at General Scott’s headquarters.

The next day, Blair told Lee that Lincoln intended to offer him command of an army being called up to defend the Union. Years later, Lee told a friend that Blair had been “very wily and keen,” playing on his sense of responsibility and his ambition. Lee declined the offer on the spot. He saw nothing but “anarchy & ruin” in secession, he admitted, yet he could not bring himself to raise his hand against his home and heritage. From Blair’s office, Lee marched straight to see Scott, uncharacteristically pushing past the general’s staff in his agitation.

Available accounts indicate that Scott tried to persuade Lee that Union forces would be big enough to stifle the South’s will to resist, making offensive action

On March 28, 1861, Abraham Lincoln promoted Lee to command of the 1st Cavalry. The Virginian accepted and again swore allegiance to the Union.

People on the street noted Lee’s grim countenance and the contrast between the sober Arlington household and the secessionists’ exuberance. Lee’s son Rooney remarked that the people of Virginia had gone mad; daughter Agnes said that Arlington felt “as if there had been a death in it, for the army was to him home and country.” For the next two dreadful days, Lee contemplated the matter. Mary Lee, as torn as her husband, said she would support whatever decision he made.

Lee left almost no record of what went on in his mind during this time. He told Smith that he must decide quickly, for resigning because of unwelcome orders was considered “dishonorable” in military circles. Yet Lee rarely uses the word “honor” in discussing his predicament; indeed, its multiple meanings under the circumstances may have made the word too weighty for him to choose. In southern society, honor was bound up with family and a desire to avoid public shame. In the army, it had to do with larger allegiances and obligations. Lee certainly shared his fellow Southerners’ humiliation at the abolitionists’ hounding, and may have reacted to it. Yet there was no clear path to rectitude in Lee’s case—every avenue was strewn with irreconcilable principles. At the same time, he was trying to avoid the disgrace of untimely resignation; for example, he contemplated dishonoring vows he had repeatedly made during his 35-year career.

And, so, his family waited as he wrestled with himself. The slaves watched their master and concluded, “He didn’t cahr to go. No . . . he didn’t cahr to go.” One cousin tells us Lee consulted the Bible. At midnight, on April 20, the house was still ablaze with lights, as the family gathered with miserable anticipation in the parlor. Finally, Lee bowed his head and wrote his resignation, as well as a short explanatory letter to General Scott. Then, he slowly walked down the staircase and handed the letters to his wife. “Mary,” he said, “your husband is no longer an officer of the United States Army.”

to fight for the South, Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs ordered thousands of Union dead buried at Arlington House, personally selecting the site behind Mrs. Custis’s gardens for a mass grave of unknown soldiers (above)." data-entity-type="file" data-entity-uuid="e3473fe3-9550-468f-ab5b-26da816c65df" height="619" src="https://www.americanheritage.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/ArlingtonCemetery.jpg" width="919" loading="lazy">

Lee developed an explanation for his decision that he would repeat nearly verbatim to the end of his days. As he often did in times of distress, he crafted it like the formulas dear to his engineer’s heart: simple, unvarying, and seemingly watertight. He told Roger Jones, another cousin in the federal army: “I have been unable to make up my mind to raise my hand against my native state, my relations, my children & my home . . . & never desire again to draw my sword, save in defense of my State. I consider it useless to go into the reasons that influenced me. I can give no advice. I merely tell you what I have done that you may do better.”

One Lee biographer called it the “answer he was born to make.” Most other historians have agreed, using such phrases as “it was not that the anguished man had any choice.” Yet everything we know indicates that it was a dreadful moment in Lee’s life. Years later, he confessed that it was so painful that he held onto his resignation letter for a day before sending it. This scene, when a strong man paced and prayed in despair, is so poignant precisely because it palpably exposes the contradiction in his heart. Even Lee’s tight-lipped language suggests he knew he must cling to his conviction and avoid expressing its contradictions, lest he second-guess his own actions.

For, in reality, there were numerous options available to him. Winfield Scott was a Virginian, and he dismissed as an insult any suggestion that he would renege on his solemn oath of loyalty. So did another Virginian, George Thomas, with whom Lee had spent Christmases in Texas. Both Thomas and Scott would suffer social ostracism for their choices. Scott was labeled a “free-state pimp;” Thomas’s relatives asked him to change his name. In all, about 40 percent of the officers from Virginia stayed with the federal forces after their state seceded. Others opted not to fight on any side. Dennis Hart Mahan, a famed West Point instructor, and another proud Virginian, chose to sit out the war. North Carolinian Alfred Mordecai resigned his commission, but rejected an offer to lead either the Confederate ordinance service or the engineers' department.

Lee wanted to avoid pitting himself against his family, but that desire would also remain unfulfilled. Cousin Roger Jones, whom he had declined to advise, decided to fight for the Union. Phillips Lee gave distinguished service in the U.S. Navy until the

No one in that family ever spoke to Lee again. With great reluctance, Smith Lee because a Confederate naval officer, where he served without enthusiasm, and, as late as September 1863, still “pitched into” those responsible for “getting us into this snarl.” Saying that both the Lees and his in-laws had pressured him with ideas that Virginia came first, he grumbled, “South Carolina be hanged . . . How I did want to stay in the old navy!” Robert E. Lee’s three sons joined the Confederate forces, but only after their father had declared his intentions. If Lee had stayed with the Union, he still would have faced confrontation without his border-state family, for numerous cousins fought for the Confederacy. But his assertion that he was acting in solidarity with a like-minded group of relatives cannot be borne out.

Nor would Lee fulfill the vow never to raise his sword again, except in defense of his state. For the first year of the conflict, he did work to keep to a defensive strategy in Virginia, but by June 1862, he had adopted the assertive policies of those who believed that offensive war was the only way to achieve southern independence. Far from refusing to take bold action, Lee became famous for his aggressive generalship. He was the standard-bearer for two invasions of northern territory, both undertaken when the Confederate government was divided about the wisdom of such incursions. Neither the Maryland nor the Gettysburg campaign could be termed defensive; and each ended most unfortunately for the South.

Two days after tendering his resignation, Lee was visited by a delegation from Richmond, which enticed him to return with them to the capital. The details of what transpired are hazy. Cousins remembered that Lee said he intended to stay out of the hostilities. After the war, Lee himself gave the not-very-convincing explanation that he went to Richmond to look over some family property. Whatever the motivation, when the train arrived, the state convention had already voted him commander-in-chief of all Virginia’s forces. Before he had time to reflect, he found himself accepting George Washington’s sword.

Was he caught unaware and forced to react too quickly, or was this really the spot where he most longed to be? Lee had grave misgivings about secession, yet excitement and opportunity were in the air, and the sparse plums of the new southern command were quickly being plucked. It is hard to say what exactly defined the

Few outside the South believed the decision reflected the noble principles Lee invoked. Honor was in the eye of the beholder in 1861, and, from the beginning, his motives were criticized. Skeptics believed that those who swore easy oaths in fine times and then abandoned them had shamefully betrayed the country. Upon learning that Lee had spent two days prayerfully searching for a decision, a cousin remarked acidly: “I wish he had read over his commission as well as his prayers.” At West Point, someone drew a picture of Lee with his head attached to the body of a louse. “I feel no exalted respect for a man who takes part in a movement in which he can see nothing but ‘anarchy & ruin’ . . . and yet that very utterance scarce passed Robt Lee's lips . . . when he starts off with delegates to treat with Traitors,” was the response of Francis Blair’s daughter, who had married into the Lee family.

Lincoln would use Lee’s “deceitful” dealings as a justification for his suspension of habeas corpus. While still in frontier Texas, Lee recognized that his decision would be based on intangibles. “I know you think and feel very differently, but I can’t help it,” he told friends. In fact, it was the personal quality of his struggle that made it emblematic of the nation’s torment. That a pensive, disciplined man made such an emotional decision still affects each American. We intuitively know that history would have been altered if the options presented to Lee—resignation, leadership of the Union troops, acceptance of high command in Virginia—had been decided differently.

Lee’s dilemma was not simply an historic wrestling match between patriotism and treachery. It stands as a critical moment in our nation’s pageant because it forces us to consider some very basic questions: What is patriotism? Who commands our first loyalty? Can loyalty be divided and still be true? It is the excruciating gray area that makes these questions universal. Lee tells us that the answer to each is highly subjective, but that they must be faced at the moment an individual is summoned, no matter how unsure or unprepared. And then, his decision tells us something more: that following the heart’s truth may lead to censure, or agonizing defeat—and yet be honored in itself.