Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August/September 2006 | Volume 57, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August/September 2006 | Volume 57, Issue 4

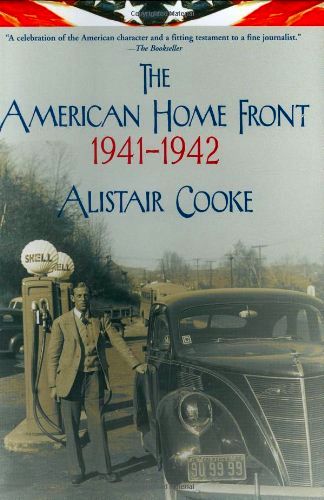

He was, to Americans of a certain age, the urbane, well-bred, well-read, well-connected Englishman who hosted “Omnibus,” a cultural lighthouse that shone over the wasteland of network television in the 1950s. Later, from 1971 to 1992, he presented “Masterpiece Theatre,” the American shop window for the best drama from the BBC.

In Britain, Alistair Cooke was perceived differently. A Lancastrian, born the son of a metalworker in Manchester in 1908, he won a scholarship to Cambridge. In the 1930s he came to Yale as a Harkness Fellow, and for good measure to Harvard as well, ditching his unappealing name of Alfred for a more attractive one. He became the BBC’s film critic and NBC’s London correspondent. His experience in America had shown him his destiny. As European politics withered in the rush to war, he moved permanently to New York, acquiring citizenship in 1941. He remained a continuing presence on British airwaves. His weekly “Letter From America” was broadcast by the BBC for nearly 60 years, ending only weeks before his death, at 95, in March 2004.

Some—including his fiancée, who ended their relationship—questioned his defection to safer shores in Britain’s most perilous hours. In truth, he did wonders for the Allied war effort, interpreting the American character to a British public conditioned hitherto by the likes of Cagney, Bogart, and Shirley Temple. He was as wont to explain the cabals of congressional back rooms as the hardships of an Appalachian miner. He did so with immaculate style, his every sentence an embarkation on a fascinating miniature voyage that would often deliver the rapt listener to an unexpected destination. His voice was smooth, velvety, hypnotic, with an intonation that to Americans sounded patrician British, to Britons that of America’s educated East Coast. His idols of form were H. L. Mencken and Mark Twain, both masters of popular enlightenment through cant-free prose.

As a child, I remember hearing his broadcasts in gray, rationed, bomb-shattered London, describing America in arresting detail. The popular perception, assisted by glimpses of lavish color ads in occasional Life s and Saturday Eve ning Post s for foods not seen in Britain for years, and by the bounty of GIs, far from home, an endless source of Life Savers and Hershey bars for grateful children, was that America, with its unbounded generosity, was a paradise that had escaped the harshness of the war that clamped Europe in its ruthless and inexorable grip.

As a child, I remember hearing his broadcasts in gray, rationed, bomb-shattered London, describing America in arresting detail. The popular perception, assisted by glimpses of lavish color ads in occasional Life s and Saturday Eve ning Post s for foods not seen in Britain for years, and by the bounty of GIs, far from home, an endless source of Life Savers and Hershey bars for grateful children, was that America, with its unbounded generosity, was a paradise that had escaped the harshness of the war that clamped Europe in its ruthless and inexorable grip.

As Cooke realized, it was a misleading, inaccurate conception that even Washington failed to appreciate. He applied for permission to visit war plants