Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2005 | Volume 56, Issue 1

Authors:

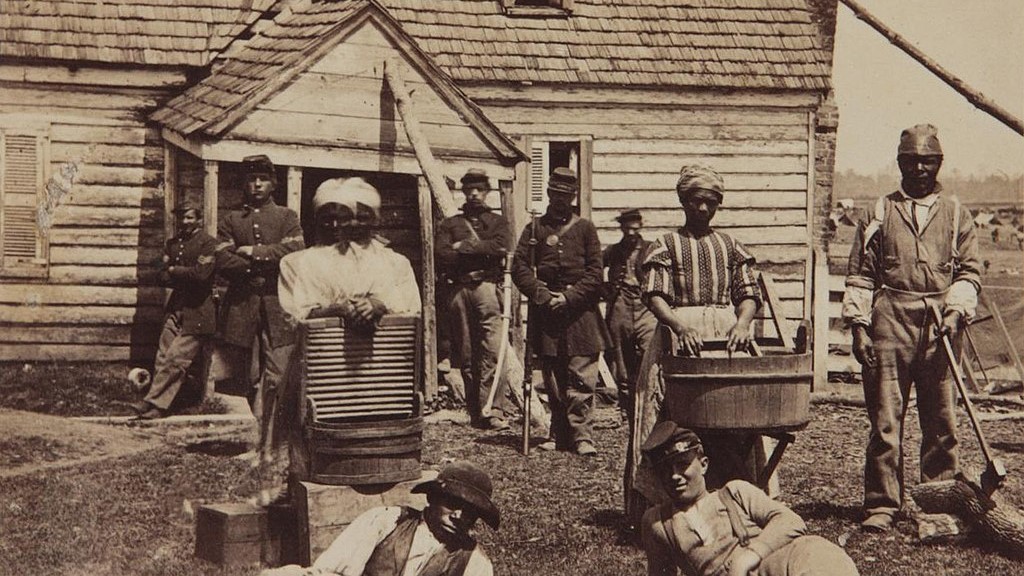

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2005 | Volume 56, Issue 1

I have long believed that what most distinguishes us from all other animals is our ability to transcend an illusory sense of now, of an eternal present, and to strive for an understanding of the forces and events that made us what we are. Such an understanding seems to me the prerequisite for all human freedom. In one of my works on slavery I refer to “a profound transformation in moral perception” that led in the 18th century to a growing recognition of “the full horror of a social evil to which mankind had been blind for centuries.” Unfortunately, many American historians are only how beginning to grasp the true centrality of that social evil throughout the decades and even centuries that first shaped our government and what America would become.

As a college undergraduate in the late 1940s, I was taught the “moonlight-and-magnolias” mythology of slavery, a mythology propagated by respected historians, as well as by popular non-academic books and by influential films from the time of The Birth of a Nation to Gone With the Wind and beyond. This mythology existed because the slaveholding South had counteracted its military defeat by winning the ideological war—or in other words, the way the 20th-century American public understood slavery and the Civil War. The effects of this victory on our racial history are brilliantly documented by the 2001 masterpiece by my Yale colleague David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory.

By 1820m nearly 8.7 million slaves had departed for the New World from Africa, as opposed to the 2.6 million whites who had emigrated from Europe.

By the 1930s, a strong consensus had emerged to the effect that the Civil War had little, if anything, to do with slavery. One school of thought held that the war had been waged over economic issues and had resulted in the triumph of Northern capitalism. A second school argued that the war had been a needless and avertable tragedy, brought on by abolitionist fanatics and a few Southern extremists. Virtually all American whites agreed that slavery had been an inefficient, backward, and increasingly marginal institution that had contained the seeds of its own economic destruction and which would have soon ended without a war. This was the view of the nation’s leading expert on slavery in the 1920s and 1930s, the Yale professor Ulrich B. Phillips.

My very liberal-minded but self-educated parents—both of them first journalists and then productive writers of fiction and nonfiction—were delighted in