Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2005 | Volume 56, Issue 1

Authors: Ellen Feldman

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2005 | Volume 56, Issue 1

In June 1952, Doubleday & Company published the diary of a German teenager who had died in Bergen-Belsen approximately a month before the concentration camp was liberated, two months before her 16th birthday. The book was translated from the Dutch. In protest against the Nazis, who had hounded her family from Frankfurt and continued to harass them under the occupation in Amsterdam, the girl had refused to write or even speak German. The publisher’s expectations were modest. The war had ended only seven years earlier. People wanted to forget rather than remember. In a nation where hotels, country clubs, and other establishments were openly restricted against Jews, and jobs and college admissions were more subtly withheld or doled out by quota, the Nazi solution to the “Jewish problem” (the term Holocaust would not come into vogue until the 60s) might lead to unsavory and unsettling comparisons. And how many readers would fork over three dollars for the musings of an adolescent girl hiding in an Amsterdam attic when millions had died and entire countries had gone up in flames?

Even in the Netherlands, the diary had gone begging for a publisher until an eminent historian praised it on the front page of a leading newspaper. The reaction to the German edition had been, not surprisingly, lukewarm. Five publishing houses in Britain and nine in the United States had turned down the manuscript. But a few American editors had seen promise, and profits. Once out in the Netherlands, the book had garnered superb reviews and sold 25,000 copies. A French edition in 1950 inspired Janet Planner to write in her “Letter From Paris” column in The New Yorker of a “slight but remarkable” book by “a precocious, talented little Frankfurt Jewess.” After initially dismissing the diary as “a kid’s book by a kid,” Double-day had bought the rights from Otto Frank, the dead girl’s father; changed the title from Het Achterhuis, which translates as “the house behind,” to Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl; persuaded Eleanor Roosevelt to write a preface, or at least put her name to one penned by Barbara Zimmerman, a junior editor and early champion of the book; and ordered a first printing of 5000 copies, a respectable number, if not one for the bestseller lists.

Two years earlier, in the summer of 1950, an American writer living on the Cote d’Azur had read the French edition of the diary. A man with a towering social conscience and a roiling sense of his own Jewishness, Meyer Levin felt as

Levin wrote to Otto Frank, the only survivor of the eight people who had gone into hiding in the dank apartment behind a warehouse and office overlooking a canal at 263 Prinsengracht, to inquire about American rights to the book and a play or movie to be made from it. When Frank replied that despite earlier rejections, he had interest from an American publisher and could not grant Levin the rights, Levin wrote back that his interest was not financial. He simply wanted to bring the diary to an American audience. After further negotiations between the two, the nature and details of which would become the substance of acrimonious lawsuits and public recriminations that dragged on for two decades, Doubleday published the book, and Levin gave it a rave on the first page of The New York Times Book Review. “Anne Frank’s diary,” he began, “is too tenderly intimate a book to be frozen with the label ’classic,’ and yet no lesser designation serves.” Though he had requested the assignment from The Times and subsequently asked for more space in which to give full rein to his enthusiasm, he did not mention to the editors that he had any connection with the book.

The review ran on Sunday, June 15, 1952. By Monday afternoon, the entire first edition had sold out. Larger printings, newspaper syndication, book club rights, and advertising and publicity campaigns followed. Meanwhile, with the encouragement of Otto Frank, Levin continued to negotiate the dramatic rights with producers and labor on a script.

I knew nothing of this history on the wintry afternoon in 1994 when I first visited the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam. I did not even want to be there. I had read the book and seen the movie in my youth. Part of a postwar generation that had grown up in the shadow of the Holocaust, I believed the house was important for the young who did not know their history and the more mature who were feckless enough to forget it, but unnecessary for the likes of me. It was a Monday, however, the Rijksmuseum was closed, and the streets, under a battleship gray sky, were inhospitable. I yielded to my husband’s importuning and made my way to 263 Prinsengracht.

If the experience did

I returned home and began research immediately, only to discover that the guide was misinformed, romantically inclined, or so bored by the repetitious nature of her work that she felt the need to embellish the account. Peter perished in the Mauthausen concentration camp on May 5, 1945, three days before it was liberated. But for me, as for so many readers of the diary, the facts were by then, if not beside the point, not the point. Peter had taken hold of my imagination and would not let go.

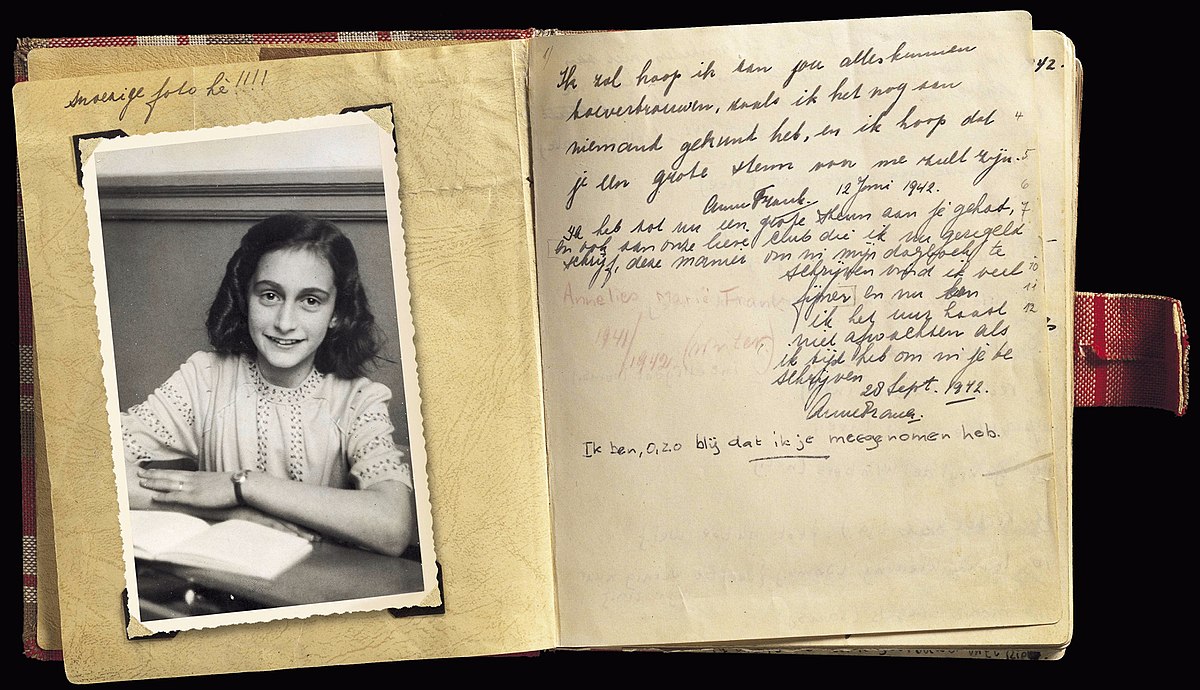

Anne Frank’s diary has been translated into 55 languages and sold more than 24 million copies. It is required reading in schools around the world. The play based on it is revived professionally at regular intervals and performed repeatedly by amateur theatrical troupes. During Otto Frank’s lifetime he corresponded with hundreds of young people who identified with Anne, though few, if any, had spent the war years hiding in an Amsterdam hovel. (In one collection of letters, a young woman asked, and Otto gave, advice on career choices and how to navigate differences with her boyfriend.) Anne’s huge dark eyes and haunting smile are instantly recognizable and have been endlessly reproduced. Recently her face appeared on a medieval tower in York, England, to commemorate a twelfth-century Jewish massacre. Anne Frank is shorthand for the shame of anti-Semitism in particular and intolerance in general. But if no one can deny Anne’s fame, which she longed for with adolescent ardor—“I want to go on living even after my death!” she wrote in her diary—60 years after she perished of typhus, critics continue to argue over the meaning and message of her words.

Meyer Levin’s play based on the diary was never produced, though a shorter radio version was broadcast

The husband-and-wife team, who had written screenplays for The Thin Man, Easter Parade, It’s a Wonderful Life, and other Hollywood comedies and musicals, were an unlikely choice. Their three Broadway plays had not been successes. Even they were uneasy about taking on the project. “I wish we were as sure that we were the people for the job,” they wrote their agent. But with Hellman’s editorial advice, and after repeated rewrites—the fact of which incensed Levin, who had been given little chance to polish his version—the play opened, on October 5, 1955, to rave reviews. “A powerful and wonderfully well played evening in the theater [that] should be around for a long time,” the New York Journal-American presciently pronounced. The critics were equally enthusiastic about the cast. In addition to applauding Joseph Schildkraut, who bore an uncanny resemblance to Otto Frank, and Susan Strasberg as Anne, they praised the Viennese-born Gusti Huber for her portrayal of Mrs. Frank. In The New York Times, Brooks Atkinson wrote that “the members of the rather boorish Van Daan family are played with perception” and “Jack Gilford’s nervous, crotchety dentist is amusing and precise.”

The play went on to win the Pulitzer Prize, the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award, and a Tony. The only honor it did not garner was the chance to represent the United States at the annual Paris International Theater Festival. The State Department opposed sending abroad during the Cold War an unflattering portrait of our German allies. Drama columnists protested, and theatergoers wrote letters to the editor, but these only fanned the publicity fires. Susan Strasberg appeared on the cover of Life . Newspapers retailed Gusti Huber’s hardships under the Nazis. “When they came to me to join, I refused,” she confessed to one columnist. She had been picked up as an enemy collaborator by the Gestapo for cursing Hitler publicly, she told another. According to her husband, Joseph Besch, a radio executive and former captain in the U.S. Army, Huber was “the first actress in Austria to be cleared by the American military government.”

Like the play, which some harsher critics, especially abroad, would come to see as a sugarcoated version of the diary—one compared the theatrical Anne with the American film, radio, and comic-book teenager Corliss Archer—Huber’s account of her past was fictionalized. In Vienna before

Huber’s faulty memory of her past is less surprising than postwar America’s lack of interest in it. The revelations about the actress attracted so little attention that when Twentieth Century-Fox filmed the movie version, she once again played the mother. Other reinventions attracted even less attention.

In the spring of 1957, a woman called Charlotte Pfeffer wrote from Amsterdam to the playwrights and to Otto Frank, who was then living in Basel, Switzerland. Charlotte Kaletta, as she was known before the war, a Christian, had been prevented from wedding Fritz Pfeffer, the dentist called Dussel in the diary, by the Nazi racial laws against intermarriage. After the war the Dutch government recognized her as Fritz’s widow and granted her his pension, and she assumed the name of Pfeffer. She wrote now to protest the treatment of her late husband in the play and prevent further defamation of his character in the coming movie. Her husband, she insisted, was not the lonely, ignorant buffoon portrayed on the stage or the dussel, which in German means soporific, dizzy, or drunk, whom Anne described in her diary.

Frank and the playwrights were sufficiently concerned about legal action by Pfeffer to consult one another, a theatrical agent, and various attorneys. Letters flew among them. Frank advised Goodrich and Hackett not to show weakness. Goodrich and Hackett wrote to Pfeffer to make clear the exigencies of the commercial theater. Had they not portrayed her husband as they did, they explained, the play would have closed on opening night, and millions of theatergoers around the world would have been deprived of an important and uplifting lesson in history.

When Pfeffer requested a copy of the screenplay to make sure

“He,” she wrote of Pfeffer, “was a handsome man, a charmer who resembled the romantic French singer Maurice Chevalier…. He was a very appealing person.” In a 1995 documentary, Gies spoke of her affection for Pfeffer to his son, Werner, who had reached America and anglicized his name to Peter Pepper, and Pepper, who had not seen his father since the days after Kristallnacht, when, thanks to his father’s foresight, he set out on a Kinder-transport headed for Britain, fought back the tears. Even the housekeeper who had worked for Pfeffer attested to his character; she urged compassion for the loneliness he had felt as a single man, without wife or child, hiding with two families, and swore to redress the wrongs done to him. “I assure you that I will do my best to tell everyone who I speak to about the play how Fritz really was,” she wrote Otto Frank in 1957.

The damage done to the memory of the other man in hiding at 263 Prinsengracht was even more egregious. On September 7, 1955, less than a month before the play’s opening at the Cort Theater on Broadway, and only a week before tryouts would begin at the Walnut Street Theater in Philadelphia, everyone involved in the production feared a flop. Act II was lagging badly. “Feeling more and more strongly that something needed in second act,” Goodrich wrote in her journal. “Sit watching play, worried, scowling.” Two days later the playwrights, the director, Garson Kanin, and Bloomgarden came up with a solution. Hermann van Pels, called Mr. Van Daan in the diary and the play, would steal bread from the annex cupboard. As David Goodrich, the playwrights’ biographer and Frances Goodrich’s nephew, described it, “Frances and Albert wrote a scene that hadn’t been in the original diary: one night, Van Daan creeps eerily, in the silent darkness, to the communal food cabinet, takes out a half loaf, and then makes a noise that wakes the others.”

Frank was not entirely happy with the invention. “Shortly after the play opened,” David Goodrich continued, “Otto Frank began worrying that the actual man’s surviving relatives might feel unhappy about being connected to a theft, even though it was fictitious.” But the scene remained in the play and was preserved

I do not believe Otto Frank intended this injustice. While the playwrights were working on an early draft of the script, he wrote them to express his discomfort at being cast as a saint. But Frank’s chief concern was to keep alive the memory and what he considered to be the message of his dead daughter. In that endeavor he succeeded spectacularly. Anne Frank has become, according to some, a lay saint. But through a combination of expediency, dramaturgy, and single-minded loyalty, Hermann van Pels, the father of the boy who captured my imagination on that winter afternoon more than a decade ago, has gone down in history as a thief, and Fritz Pfeffer as a dimwitted clown.

Perhaps the most curious aspect of this defamation of two dead men is that despite 20 years of court actions and publicity battles, no one, except the journalist quoted above, has sought to set the record on them straight. Meyer Levin wrecked his health, ruined his marriage, sacrificed his family, alienated friends and supporters, exhausted several psychiatrists, and spent a great deal of the money he made on his hit book, play, and movie Compulsion trying to convince the world that he spoke in the true voice of Anne Frank. He never, however, uttered a word publicly about the silencing and betrayal of two other victims of the same horror.

Even before the play opened, Levin had filed suit against Otto Frank for breach of contract and fraud. He had also taken an ad in the New York Post, headlined A CHALLENGE TO KERMIT BLOOMGARTEN (sic), demanding that his play be given a public reading and that the world be allowed to judge his attempt “to dramatize the Diary as Anne would have.” After the play’s opening, he brought charges of plagiarism as well. He would eventually win the suit for plagiarism in court, though the judge set aside the award of $50,000, on the grounds that the jury was not professionally competent to decide the amount, and ordered a new trial. As the legal proceedings dragged on, Levin repeatedly signed agreements, only to violate them by speaking publicly of the matter, or negotiating for a performance of his version of the play, or infringing the settlement in some other way.

There were no heroes and only unintentional victims in the legal battle Meyer Levin waged against Otto Frank. Though most people involved had good intentions,

Among Levin’s papers in the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University there is a copy of a letter from Frances J. McNamara, a research consultant for the House Un-American Activities Committee, to Victor Lasky, of the American Committee for Liberation, referring to HUAC reports on Kermit Bloomgarden and others involved in the production of the play. There are also letters from Levin to various Holocaust survivors requesting information about Otto Frank’s conduct in Auschwitz and the reasons for his survival when so many others perished. After these dangerous insinuations and outright calumnies, it is a giddy relief to come across Levin’s letter to George Stevens, the director of the film version of the diary, suggesting the casting of Levin’s stepdaughter as Anne. He was not offering a quid pro quo, he assured Stevens; he was merely fostering goodwill that might bring an end to the long legal war.

The terrible irony of Levin’s steadfast insistence that he spoke in the true voice of Anne Frank was that when Holocaust deniers turned their sights on the diary, they found ready ammunition in Levin’s words. In addition to contending that Anne and Peter were not Jewish names and that the emotions expressed in the diary and the language in which they were couched were too sophisticated for a teenage girl—I like to think Anne would have cherished those criticisms—the deniers cited Levin’s award in the plagiarism suit. “The well known American Jewish writer, Meyer Levin, has been awarded $50,000 to be paid him by the father of Anne Frank as an honorarium for Levin’s work on the ’Anne Frank Diary,’” wrote The American Mercury. “Mr. Frank … has promised to pay his race kin” for the dialogue he “implanted” in the diary. The inclusion in one American edition of photographs not of Anne but of the young women who had played her onstage did not help, and Otto Frank often told of the fan he met in an American bookstore who was astonished to learn that Anne had actually existed.

Whether Anne Frank’s diary is recognized as fact or mistaken for fiction, reviled by Holocaust

Certainly Anne’s talent was extraordinary, and her perceptions were remarkable for a girl her age, but even an extraordinary 13- to 15-year-old is an unlikely voice for six million dead. It is just that unlikelihood, however, that makes Anne’s diary such an overwhelmingly human document. She was not a historian putting the events of the day in perspective, or a philosopher trying to make sense of the senseless, or a journalist probing the behind-the scenes maneuvering of a criminal order. She was a girl, on her way to becoming a woman, trying to survive the events and ultimately failing, and as such she has put a human face, a child’s hauntingly questioning face, on six million faces erased from the 20th century.

There is another reason that Anne’s diary has captured the world’s imagination, and it is more disturbing. I have said that Anne was a child on her way to becoming a woman. The diary is, above all, a closely observed and deeply affecting coming-of-age story. Outside the curtained windows of the annex, Nazis and their Dutch collaborators prowled the streets, sirens wailed, and Jews and Gypsies and homosexuals and political prisoners boarded the trains for the East, but until the Green Police mounted the stairs to the annex, all that horror remained outside. If Anne and the others in hiding could not shut out the threat or banish the fear for a moment, and a careful reading of the diary shows they could not, the reader, thanks to Anne’s skillful rendering of mundane affairs and churning emotions, can. Otto Frank always claimed that “Anne’s book is not a war book. War is the background.”

Frank also emphasized, and the people who brought the story to the stage and screen stressed, the essential optimism of his daughter’s message. The entry in the diary that serves as a coda

This willfully sunny interpretation has served neither Anne nor history well. In 1997, the novelist and critic Cynthia Ozick argued, as had Meyer Levin decades before, that the diary has been misunderstood, misinterpreted, and misrepresented by even its greatest champions. “It may be shocking to think this (I am shocked as I think it),” Ozick wrote, “but one can imagine a still more salvational outcome: Anne Frank’s diary burned, vanished, lost-saved from a world that made of it all things, some of them true, while floating lightly over the heavier truth of named and inhabited evil.”

I cannot share Ozick’s wish for Anne’s oblivion. I cannot condemn to silence the heartbreakingly resonant voice of that girl in hiding, merely because it does not say what some want to hear or because some choose to hear in it things she never said. I wish her portraits of the two men in hiding with her family were recognized as outbursts of adolescent disaffection rather than reliable observation. I wish the reputations of those two men who shared her fate had not been sacrificed to the need to keep an audience laughing in one act and on the edge of its seat in another. I wish the young girls who wrote to Otto Frank had responded to the threat closing in on Anne and others like her as passionately as they identified with her anger at her mother and affection for Peter. I wish that Anne Frank’s name had not become the battle cry of vicarious victimhood. But I am grateful the diary has survived. It must not be taken as the only, or even the chief, document of the Holocaust. Its personal trials must not be permitted to overshadow the cosmic horror that hovers over them. But it must continue to be read. We need a single sharply etched face to see those six million that have blurred. We