Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 4

Editor’s Note: Dr. Lonnie G. Bunch, III is the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and founding director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. The following essay was adapted from his introduction to the recent book Tragedy on Trial: The Story of the Infamous Emmett Murder Trial by Ron Collins.

One of the core principles at the heart of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture is to tell the “unvarnished truth,” a phrase often used by the late Dr. John Hope Franklin, the dean of African American historians. So much of a historian’s job is to uncover truths in the past, no matter how complicated or painful. We do it through intensive scholarship and meticulous research that leads to new evidence, new insights, and new interpretations.

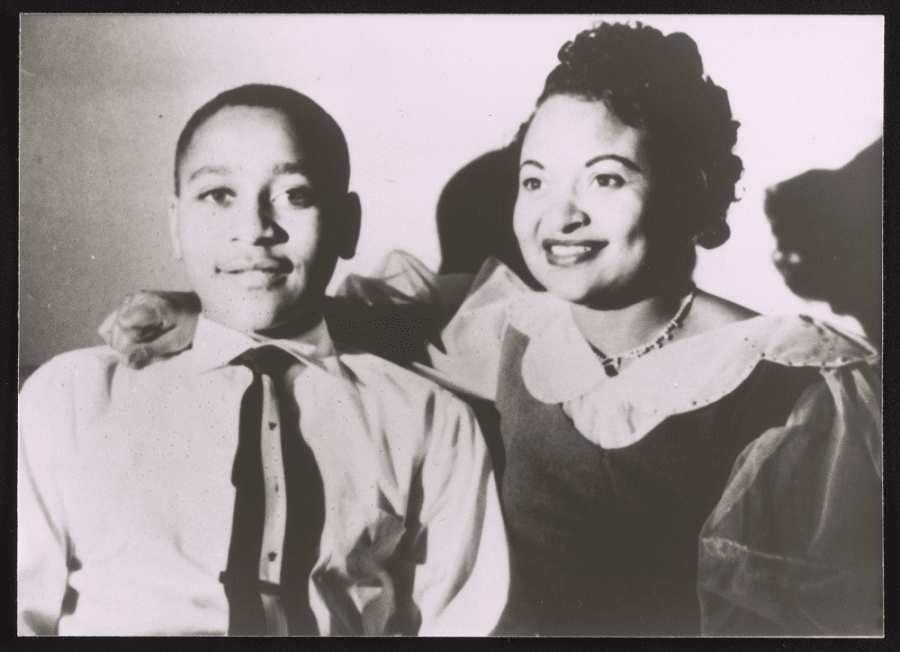

Although the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi was one of the key moments in the civil rights movement, important details about his killers and the woman who accused him of impropriety have only emerged over the past several years. Historian and law professor Ron Collins makes extensive use of a copy of the long-lost transcript of the trial of Roy Bryant and his half-brother J.W. Milam, the two white men charged with killing the boy and tossing his body into the Tallahatchie River.

It is a story that had been lost to time, and, as is often the case with historical examples of racial terror and injustice, it was also buried by people determined to obscure their own roles in maintaining a system that allowed it to happen.

Despite overwhelming evidence to support a conviction, his murderers were declared not guilty by an all-white jury in Sumner (self-advertised as "A Good Place to Raise a Boy") that deliberated for 67 minutes. The defense had originally tried a justifiable-homicide argument, based on Carolyn Bryant's claim that Emmett had assaulted her. Then, they switched to the claim that the body found in the river was not Emmett's, even though his mother had identified him, and his father's ring was on his finger. The jury went with the notion that the body could not be identified.

The killers' several accomplices were never charged.

Although the murder of Emmett in a barn at Shurden Plantation in Sunflower Country was one of the most pivotal events in American history, it was also sadly unremarkable, typifying the casual destruction of Black bodies in the Jim Crow South. In the crucible of racial terror in 1950s Mississippi (a state so tethered to its slaveholding past that it did not ratify the Thirteenth Amendment until 1995), the lynching of the boy known by his loved ones as Bo could have been nothing but just another Black boy killed. Another false accusation of sexual impropriety used as a pretext for racist violence. Another statistic.

Were it not for Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley (Bradley, at the time), those in power may have been able to act as so many others had before, protected by a racist system and shrouded in obscurity.

Mrs. Till-Mobley refused to allow the nation to look away, despite the incomparable pain of the death of her child, and this changed the country forever. When she chose to have an open-casket funeral at Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago, and allowed pictures to be taken of Emmett’s disturbingly disfigured face, it became a catalyst that reignited the civil rights movement.

To that point, much of the work done in the fight for equality had been in courtrooms, and included taking arguments all the way to the Supreme Court. But milestone victories like Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which formally (but not actually) banned segregated schools, although vital, were not enough to counteract the entrenched racism of the South. Indeed, they only served to spur violent backlash — including Emmett Till’s murder.

When Black World War II veterans returned home from Europe and Asia, they attempted to change things to reflect the freer and fairer lives they had experienced overseas, but those efforts were mostly carried out at the local level. Emmett’s murder was the first event to serve as a national wake-up call and to galvanize people. It demonstrated that folks had to confront the evils of segregation head-on and that all people of conscience must be active participants in improving the country.