Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

| Volume 1, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

| Volume 1, Issue 1

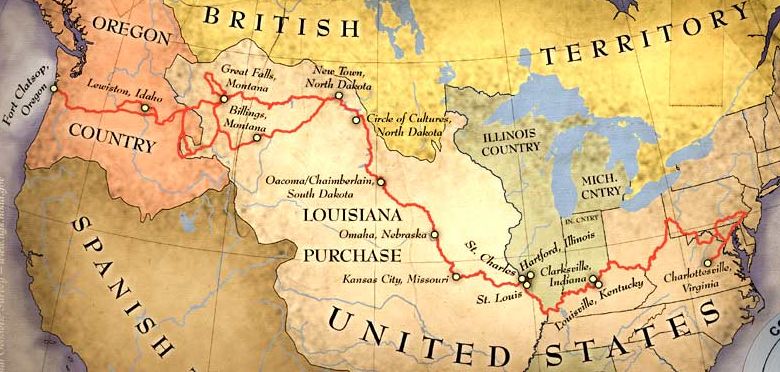

Most of us know the basic story of the Lewis and Clark expedition sent by President Jefferson to explore the lands acquired in the Louisiana Purchase. They crossed the continent between 1803 and 1806 in one of the great heroic accomplishments in American history.

Of course, many Native American tribes don’t quite see it as heroic. “They didn't know where they were going,” said LaDonna Brave Bull a few years ago. “They had no knowledge of the country. To us, they were like these people wandering around in the wilderness lost."

Lewis and Clark never published reports of their discoveries. The better educated of the two, Meriwether Lewis, killed himself in 1809 in a tavern on the Natchez Trace in Tennessee, or maybe he was murdered. It did seem odd for someone to have committed suicide by shooting themselves in the head twice.

When Clark heard of his partner’s death, he is reported to have exclaimed, “I fear O!...What will become of his papers?”

In fact, the detailed diaries that Jefferson had ordered Lewis, Clark, and the sergeants on the expedition to keep were never made available. In 1810 Nicholas Biddle, a young lawyer who later became first president of the Bank of the United States, started an abstracted version of a report, but couldn’t find a publisher and turned the effort over to another author who eventually published an even more abbreviated report on the journey. In the years that followed, the memory of Lewis and Clark’s achievement grew dim. Many 19th Century histories barely mentioned the expedition at all.

That changed thanks to Elliott Coues, a young army surgeon and ornithologist. In 1872 he had published his Key to North American Birds, considered the most important book on the subject since Audubon’s Birds of America. It did much to promote the systematic study of ornithology.

Coues went on to publish many more important books and studies, and helped establish the current taxonomic classification of species, not just in ornithology, but the whole of zoology.

In the early 1890s, Coues was preparing the first scholarly reprint of the abbreviated Biddle history of the Lewis and Clark expedition, and got in touch with Nicholas Biddle’s son, Craig. Coues asked the question no one had thought to ask before: What had happened to the original journals of Lewis and Clark?

“Why, don’t you know?” was the response. “They’re in the library of the American Philosophical Society, where my father left them many years ago.”

Historian Anthony Brandt wrote in American Heritage a few years ago that, “To Coues it was as if he had discovered the Comstock Lode.” The material would finally be published in 1904-6 after being lost for a century.” They were incomplete – to be sure, missing parts have since turned up – but they were full enough to be