Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

| Volume 1, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

| Volume 1, Issue 1

Before August 17, 1896, Americans had little interest in Alaska, a far-off “district” — not even a territory — full of wolves and ice and forests. That attitude started to change 128 years ago, when a Tagish Indian known as Skookum Jim spotted something shimmering among the stones in a creek near the Yukon River. The Klondike Gold Rush began as soon as news of the discovery reached the states, and between 1897 and 1899, one in every 700 Americans had abandoned their home and set out for the “Golden River.”

More than a half million pounds of gold have been found in the Yukon since 1896. Yet the story of the men and women who did the mining is more valuable than all that ore. The sudden rush into the Northwest, as well as the equally sudden retreat, poses a big question: Why did so many late-19th-century Americans decide to leave their farms and factories to search for gold in a faraway, brutal, and alien place?

The man whose discovery sparked that strange migration, Skookum Jim Mason, was himself a character from a different world. “Skookum” is slang for “super” in the Chinook language, and Jim certainly earned his nickname. Well-known as a packer (a mountaineering porter) for white men, he could supposedly heft hundreds of pounds of bacon down rugged, miles-long trails. He was said to have once killed a bear with an unloaded rifle and a pile of rocks. His greatest achievement, though, was simply bending over and picking a gold nugget out of Rabbit Creek.

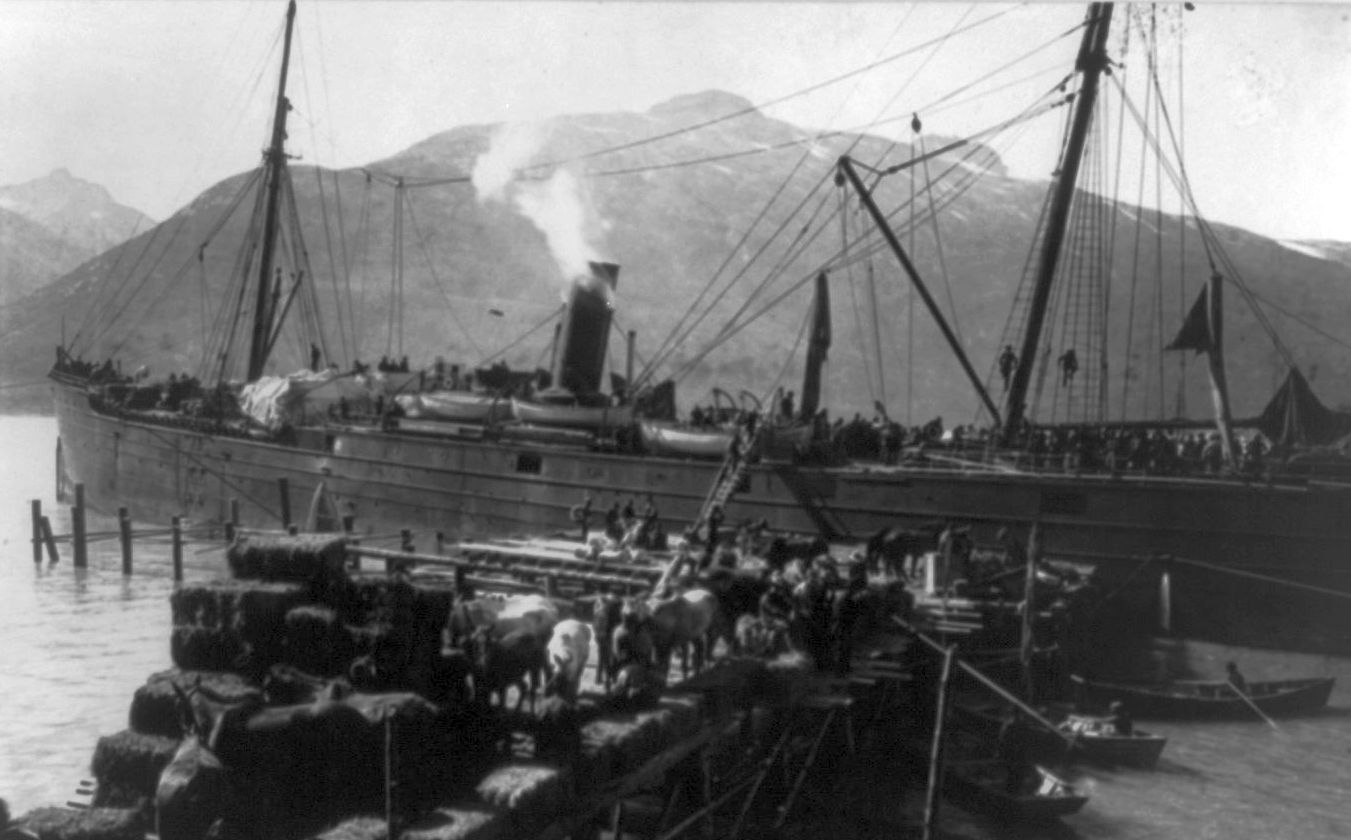

Eleven months later, he and several relatives steamed into Seattle hauling bags bursting with nuggets and bottles filled with gold dust. The whole country soon buzzed with the news: A million dollars in gold had already been found, and there was plenty more just sitting in Alaska’s creeks and streams.

America was very susceptible to Klondike fever. The nation had just survived a devastating depression. At a time when workers were lucky to make 10 cents an hour, gold was worth $17 an ounce. A single nugget might equal a month’s wages.

Gold was also a hot political commodity. The gold-standard debate, about whether to continue to link every dollar solely to an amount of gold in the U.S. treasury, lay at the center of the 1896 Presidential election. William McKinley’s victory over William Jennings Bryan confirmed the metal as the basis of U.S. currency and proved that the