Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 1

Editor's Note: Catherine McNeur is an associate professor of history at Portland State University and is the author of Taming Manhattan and Mischievous Creatures: The Forgotten Sisters Who Transformed Early American Science, in which portions of the following essay appear.

Shifting and hoisting her skirts to make her way through the narrow rows of wheat with her net, knife, magnifying glass, and containers, the entomologist Margaretta Hare Morris was on a mission. Her neighbors’ field showed signs of a fly infestation. “Prompted by no other motive than a love of study,” she recalled later, “this, to me, new insect was an object of peculiar interest.” She wanted to observe the fly with her own eyes, to study its behavior, to collect specimens, and, most importantly, to devise a strategy to stop its spread.

Cutting off sections of infested wheat with her knife, she carried the awkward bundle home to place it under bell jars in the library that she and her sister, the botanist Elizabeth Carrington Morris, had created on their third floor. She hoped to watch the flies mature and transform. As she was fond of saying, “an evil investigated and understood is half-remedied.”

American women have been scientists since before the sciences were even an established profession, though that history has largely been forgotten. Though the nineteenth-century Philadelphia sisters, Margaretta and Elizabeth Morris, would come to win acclaim for their discoveries, they faced an uphill battle to be taken seriously by their male peers.

Later in her career, Margaretta would be one of the first women elected to American Association for the Advancement of Science, and she and Elizabeth were in conversation with Charles Darwin, Asa Gray, Louis Agassiz, and other major scientists who benefited from their discoveries. The path to that hard-won recognition began with those tiny wheat flies.

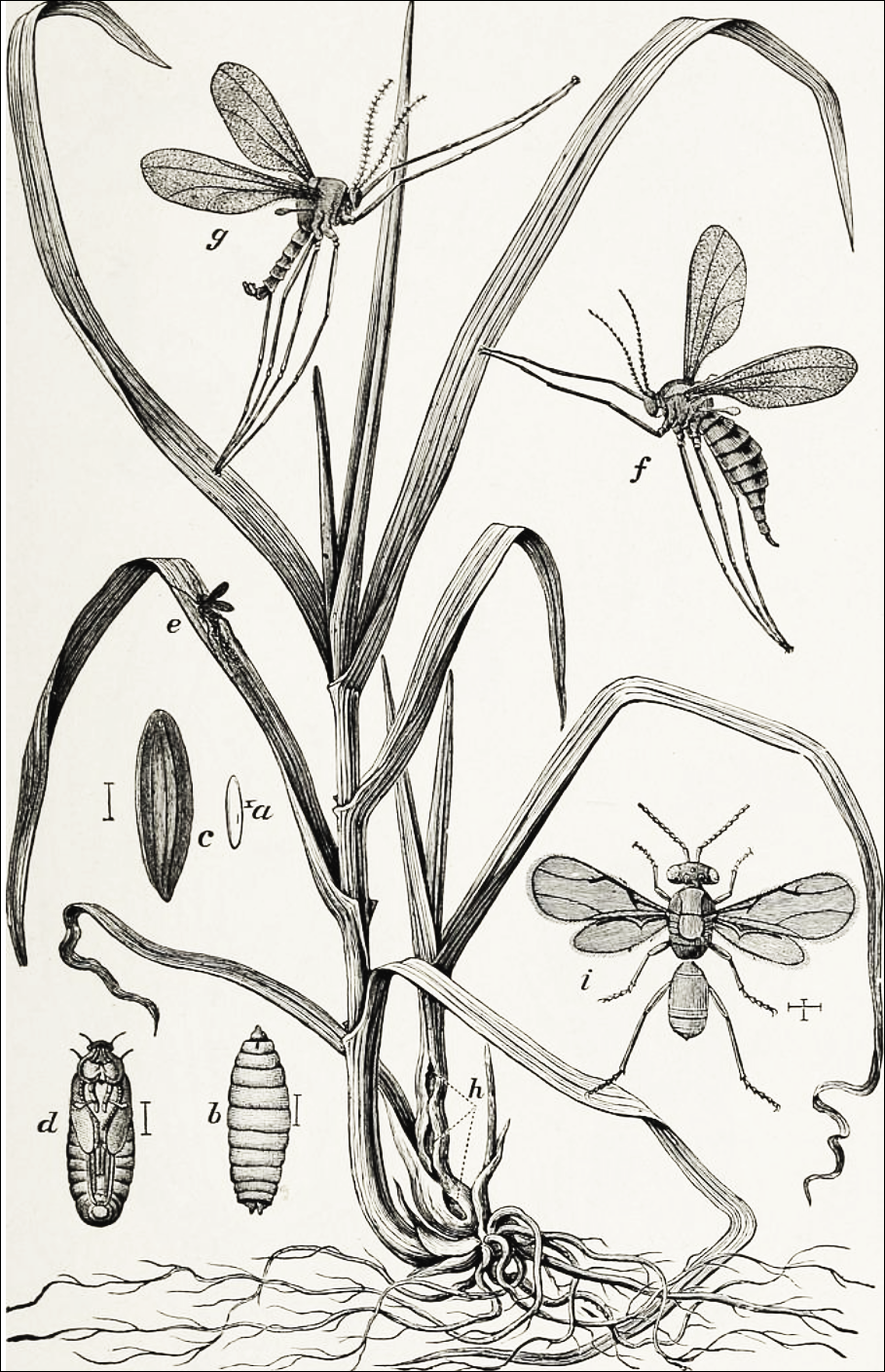

Margaretta realized that something was amiss in the summer of 1836 when she noticed that her neighbors’ field was not the only one suffering. Newspapers and a few agricultural journals were beginning to report on how Hessian fly larvae were gorging themselves on young wheat plants. Margaretta noted that the fly was appearing around Philadelphia in “appalling numbers” that had not been seen for a generation. The Hessian fly, or Cecidomyia destructor, was capable of devastating wheat yields, creating cascading consequences for farmers and consumers alike in a culture that was so dependent on flour and bread.

At the front lines in the fight to stave off the pests were American farmers, who had been disagreeing about