Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2024 | Volume 69, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Gregory J. Wallance is a New York-based lawyer and author of several books, including the recently published Into Siberia: George Kennan's Epic Journey Through the Brutal, Frozen Heart of Russia, from which he adapted this essay. His new book tells the dramatic story of George Kennan’s years of exploration in frozen Siberia, and his travels to investigate and expose the brutal tsarist prison system. Wallance witnessed Russian cruelty during the Cold War when he went to the Soviet Union to help Jews emigrate and met courageous dissidents such as Andrei Sakharov and his wife, Yelena G. Bonner, who sacrificed so much in the fight for freedom in their time.

In mid-June 1885, a four-wheeled, horse-drawn carriage called a tarantas entered a small forest clearing just east of the Ural Mountains in Russia. At the center of the clearing stood a twelve-foot-high brick pillar, which marked the Siberian frontier. The driver brought the three-horse team to a halt, calling out to his passengers, “Here is the boundary.” Two Americans in tweed traveling suits climbed out of the carriage.

George Kennan, a 40-year-old journalist, walked around the pillar, which had a facade of crumbling white stucco. He was a thin, sinewy man who stood ramrod straight. He had dark, piercing eyes, black hair flecked with gray, a well-groomed handlebar mustache, and an ample supply of resourceful energy. He had come to Russia on assignment for a widely read American journal, The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, to investigate the Siberian exile system. His companion, George Frost, a burly, forty-two-year-old Boston artist, pulled out a sketch pad. He was there to provide the illustrations for Kennan’s articles.

Standing before the pillar, Kennan, who considered himself a friend of Russia, could not have imagined that his findings would inflame the American public against the tsarist regime and shape enduring attitudes toward Russia.

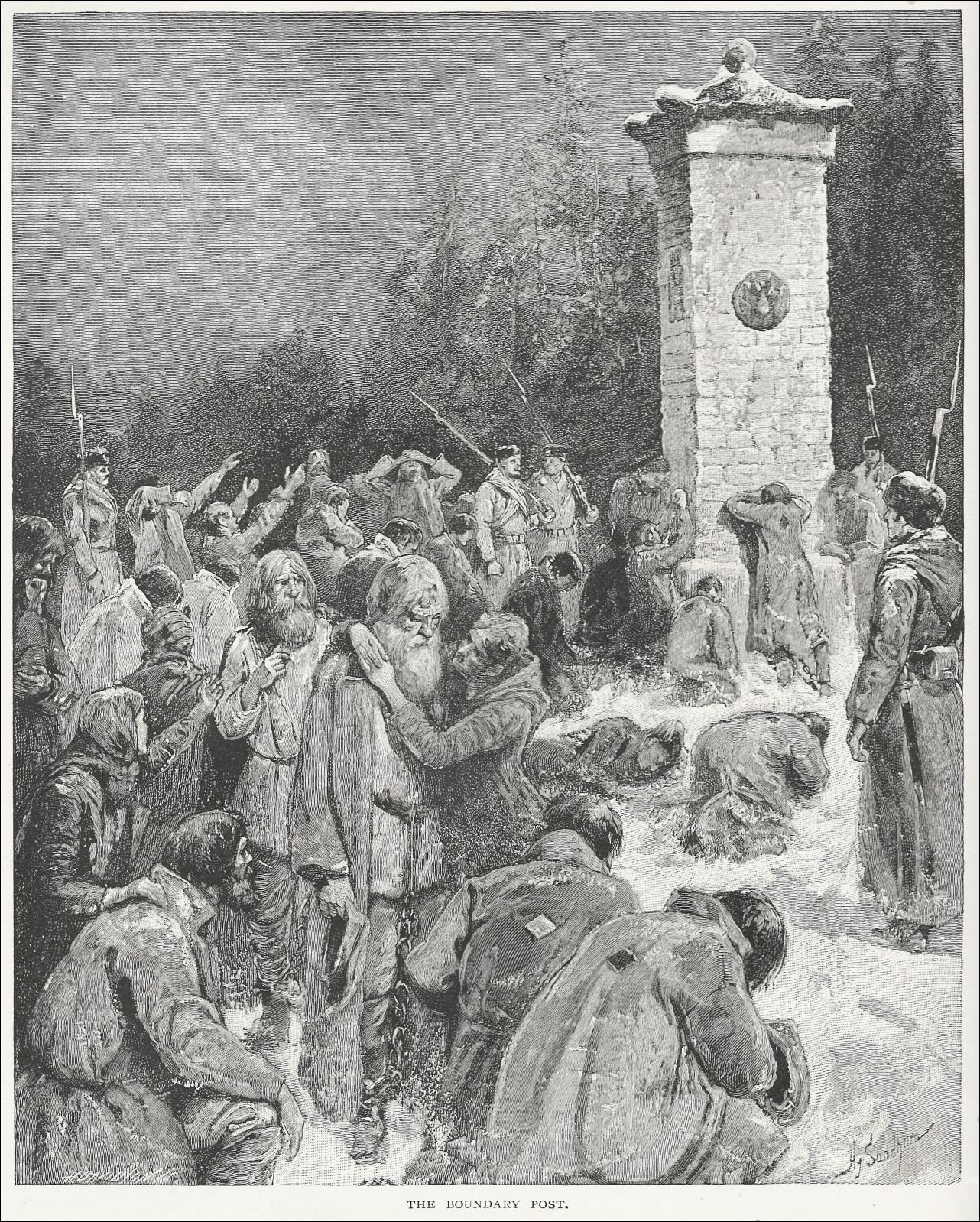

Ghostly convicted criminals haunted the clearing in the forest. In an earlier era, the convicts, bearded and gaunt after months of marching from European Russia, had been allowed by their guards a brief stop at the pillar. Some kissed the European side of the pillar, while others pressed their tear-soaked faces to it. Convicts collapsed to their knees and buried their faces in the earth. Some hugged each other or dug up handfuls of dirt to take with them. A few scraped their names or inscriptions on the pillar. “Farewell life!”

The exile convoy commander shouted an order to form ranks. With a clinking of their chains and shackles, the convicts assembled, crossed themselves, and resumed their march to the east.

change American and European attitudes to Russia with his exposes of the tsarist abuses." data-entity-type="file" data-entity-uuid="cc20b45b-a9bb-4e91-a3d9-beb9d6547253" height="404" src="https://www.americanheritage.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/Kennan%20in%201885-Library%20of%20Congress_0.jpg" width="311" loading="lazy">

Of those who survived to reach their Siberian destinations, few managed to return to Mother Russia after their sentences ended, which is why convicts wept at the pillar. Exiles included both criminals convicted after a trial and opponents of the regime, who were generally sent to Siberia without any judicial process. The practice was to shackle and chain convicts sentenced to hard labor in Siberia.

A few years before Kennan’s investigation, the Russian government had completed a railroad line that transported exiles across European Russia and over the Ural Mountains, apparently without stopping at the boundary pillar.

But, since the Russian rail network did not yet penetrate far into Siberia, the exiles still had to march thousands of miles from the railhead to Siberian prisons, mines, and factories. Like their predecessors at the boundary pillar, few saw their homes again.

After contemplating the “grief-consecrated pillar,” as Kennan called it, he and Frost climbed back into their carriage and rode into Siberia, which was so immense that it could swallow Europe (excluding Russia), the United States (including Alaska), and still have more than enough room for Texas. They were unfazed by the challenge of a long Siberian journey because they were fit men who were familiar with hardship and privation.

The following March, Kennan and Frost stumbled out of Siberia. Frost had suffered a nervous breakdown; he had paranoid delusions and needed medical treatment. Kennan’s face was old and sunken, and he had difficulty walking. His wife barely recognized him when they reunited in London.

Today, George Kennan is a too-little-remembered American whose achievements have been overshadowed by a much younger, distant cousin, the diplomat George Frost Kennan, who was the chief architect of America’s Cold War containment strategy. The George Kennan of the Gilded Age was an intrepid explorer and leading journalist and war correspondent. After his Siberian investigation, he became a moral force whose writings and lectures about the inhumanity of the exile system compelled Russia to implement reforms.