Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 7

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 7

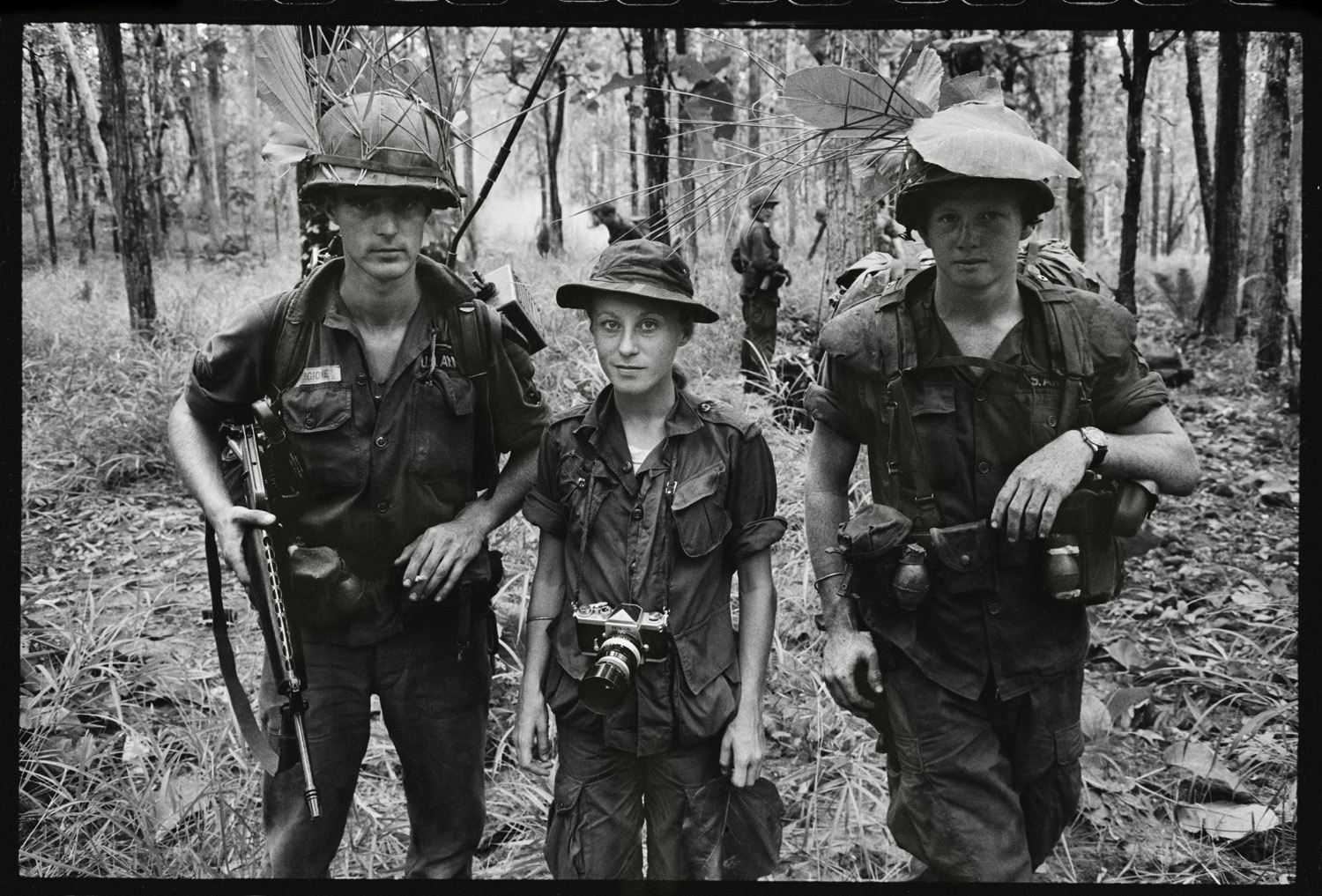

Editor’s Note: Elizabeth Becker is a respected war correspondent and award-winning author, having worked for The New York Times, National Public Radio and the Washington Post. Among her books is You Don't Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War, from which the following was adapted.

When they gave the twenty-minute warning, Catherine Leroy was waiting in her assigned seat on the left side of the C-130 cargo plane, the air thick with the heat of Vietnam’s dry season. She was quiet, trying to blend in. Leroy was the only journalist on the plane, the only photographer. She had two cameras draped around her neck, and she was the only civilian and the only woman. Her US Army-issued parachute nearly swallowed her. At five feet tall and weighing just 87 pounds, she was tiny compared to the dozens of US Army parachutists sitting alongside her.

It was February 1967, and Leroy had been selected as the best person to capture on film the United States’ first airborne assault in the Vietnam War. The Pentagon hoped to repeat in the tropical jungles of Southeast Asia the success of World War II airborne operations that helped shift the course of that war. After more than a year of mixed results, the US military wanted a big win.

The day before, Leroy had been called to the Office of Public Information at the Military Assistance Command Vietnam or MACV, the headquarters of the US Armed Forces in Saigon. Not sure if she was in trouble, Leroy was relieved when she was asked just one question: Did she still want to jump?

Shortly after that, she was assigned to the 173rd Airborne Brigade and sworn to secrecy until the operation began. She barely slept, rose with the troops before dawn, and climbed onto the truck convoy to Bien Hoa Airport, 16 miles northwest of Saigon. She boarded the seventh plane to shouts of “Airborne all the way!”

The target was a battleground near the border with Cambodia. Leroy listened as the plane rose, excitement overwhelming her. Her stomach cramped.

The cavernous plane flew for more than an hour before the paratroopers heard the telltale drone of the engine slowing, signaling that the pilot was near the target zone. She photographed the game faces of the soldiers the moment the jumpmaster began the countdown. “Get ready! Stand up! Hook up! Check static lines!”

Soldier after soldier hooked onto the line of steel cable suspended above them, stamping their feet and shouting. The green light above the door lit up. “Go!”

back and forth under an Army parachute. " data-entity-type="file" data-entity-uuid="28007e8a-a190-4a91-82a5-69a266c8a24c" height="981" src="https://www.americanheritage.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/003DCL_Vietnam028_web.jpg" width="852" loading="lazy">

Leroy fell in with the others. The jumpmaster grabbed the static lines, guiding each soldier out with a “go, go, go, go.” Like a controlled explosion, the men thundered down the long dark aisle toward the back of the airplane, Leroy keeping pace with them.

She jumped out the door, butterflies in her stomach, her dark blond pigtails lifting as she fell. Then: “Everything became light.” Her parachute opened into the cool air, with no trace of wind. From above, the menacing jungle was an undistinguished blur of deepening shades of green. Almost beautiful.

She grabbed the Leica, then the Nikon cameras around her neck, and photographed the hundreds of parachutes as they opened. She shot their images from above and below and sideways. Even in their helmets and heavy boots, the soldiers reminded her of flowers opening their petals. In no time, the lush earth raced up to meet her. “I landed in a drained rice paddy, lovely and springy and soft, rolling over in my easiest landing.”

Operation Junction City looked majestic in Leroy’s photographs that first day. Soldiers hit the ground running. This tropical assault was a search-and-destroy mission in Tay Ninh Province in southwest Vietnam. The soldiers dispersed over rice paddies and villages looking, sometimes blindly, for the elusive headquarters of Vietnamese communists.

Stunned villagers huddled near their empty huts, ordered out by towering American soldiers in a search-and-destroy mission. Their faces resigned, the villagers were rounded up and banished from their homes, leaving behind ancestor altars and pig stys. They cradled bedrolls and cooking pots; they were displaced to refugee camps.

With so much riding on the operation, other reporters had demanded to be on the ground with the paratroopers. Many were upset, some even disdainful, when they found out that Leroy would be the only accredited journalist to jump. For over a year, she had been the only woman combat photographer in Vietnam and had given up trying to change men's attitudes.

Even the great photographer Don McCullin, who admired her work, was taken aback seeing her on the battlefield. “She did not want to be a woman amongst men, but a man amongst men. Why would a woman want to be amongst the blood and carnage?… I did have that kind of issue with Cathy.”

After the initial landing, the rest of the press arrived by land and filed their stories. The next morning, Brig. Gen. John R. Deane showed up in the press tent with a surprise for Leroy. He pinned the master jump-wings badge, its gold star signifying a combat jump, onto