Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2002 | Volume 53, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2002 | Volume 53, Issue 1

Half a year ago, Amherst, Massachusetts held a meeting to discuss hanging American flags along the town’s main routes. The head of the local Veterans of Foreign Wars chapter had spent $1000 on 29 flags, hoping to fly them for months at a time, instead of just on national holidays, as was the town’s original plan. A physics professor from the University of Massachusetts rose to object. The Stars and Stripes, she explained, was “a symbol of terrorism and death and fear and destruction and oppression.” Normally, such a protest would not make national news, but the meeting was held on the evening of September 10. Over the next few days, the professor was widely quoted and subsequently bombarded with furious phone calls and e-mails. Meanwhile, across the country, American flags blossomed in a profusion certainly not approached since World War II, or perhaps ever.

The flag has weathered a variety of national attitudes since it first flew, ranging from reverence to indifference, but what we are witnessing now is its return from an era unique in our history, the sour aftermath of Vietnam, when it became nearly as divisive a symbol as it had been on the battlefields of the Civil War.

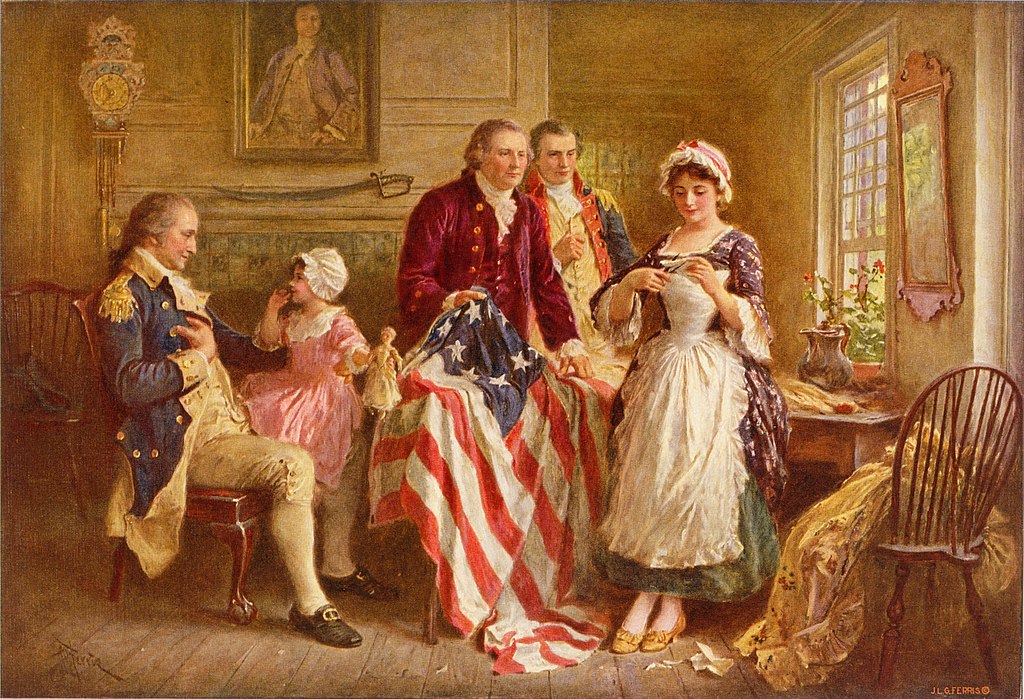

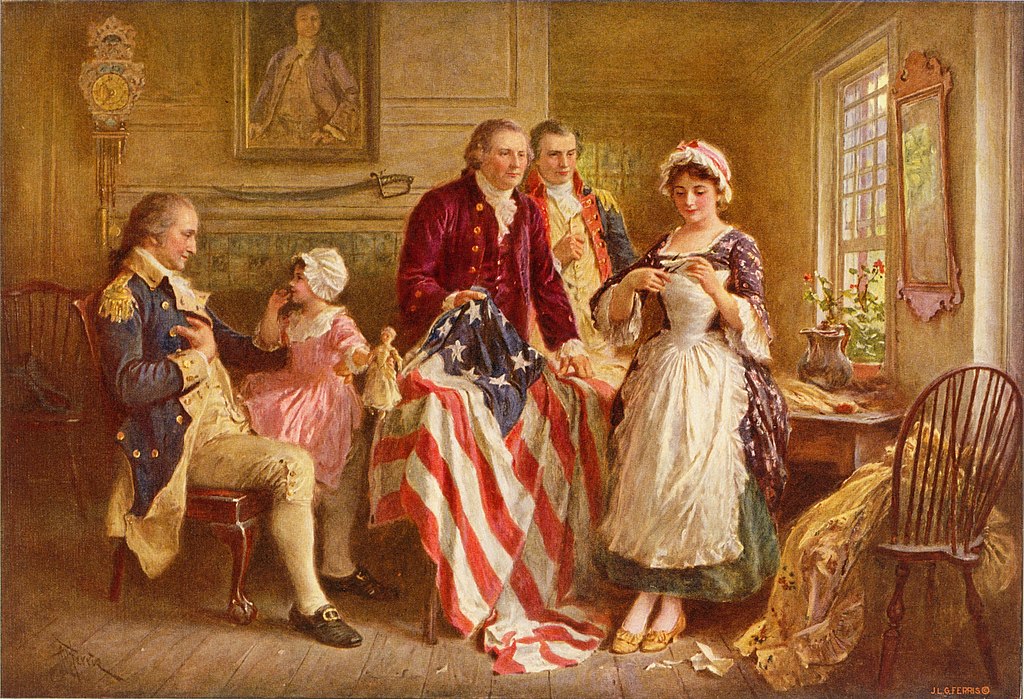

The flag and American patriotism have always been interwoven. The national anthem, written during the War of 1812, is not about the land or people but about the survival of the banner during a night assault on Baltimore Harbor. Betsy Ross’s involvement with its creation may be mythical, but her home is nonetheless a national shrine.

“The flag is the embodiment, not of sentiment, but of history,” said Woodrow Wilson, and it is perfectly true that the country and the banner were created at the same time. On June 14, 1777, the Continental Congress approved the design of a national flag, mandating that it “shall be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the Union be thirteen stars, white on a blue field, representing a new constellation.” Despite this congressional decree, the flag was not a potent symbol in early America; for one thing, there were no early laws to standardize its appearance. To alleviate the resulting confusion, President James Monroe signed a bill on April 4, 1818 directing that the flag have “thirteen horizontal stripes of alternate red and white [some people had been crowding the banner by adding a new stripe with every new star]; that the union have twenty white stars in a blue field; that one star be added on the admission of every new state in the Union.”

By 1831, the uniform design had established enough of a hold on American sentiments that