Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

October 2001 | Volume 52, Issue 7

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

October 2001 | Volume 52, Issue 7

In 1517, Martin Luther took a stand on it. In 1926, Houdini made his final exit on it. In 1938, Orson Welles perpetrated a national hoax on it. Today, 70 percent of American households open their doors to strangers on it, 50 percent take photographs on it, and the nation drops more than six billion dollars celebrating it. The night is Halloween, of course, and the history of its rise is as unlikely as any ghost story. Halloween has become the darling of American holidays. Only Christmas outearns it. Only New Year’s Eve and Super Bowl Sunday outparty it.

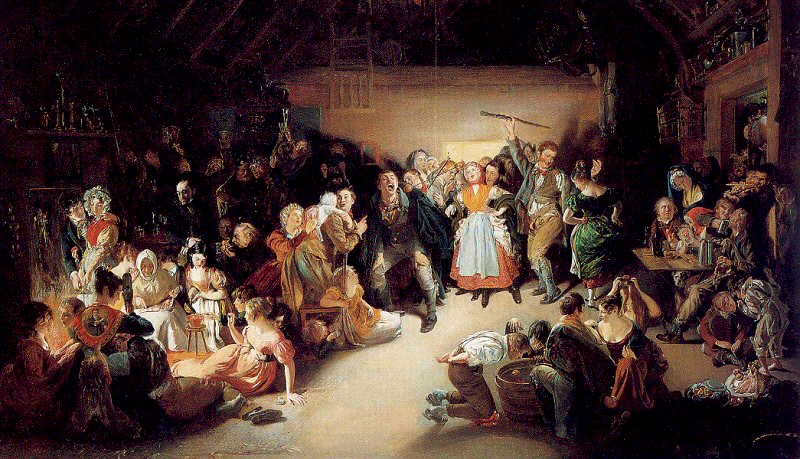

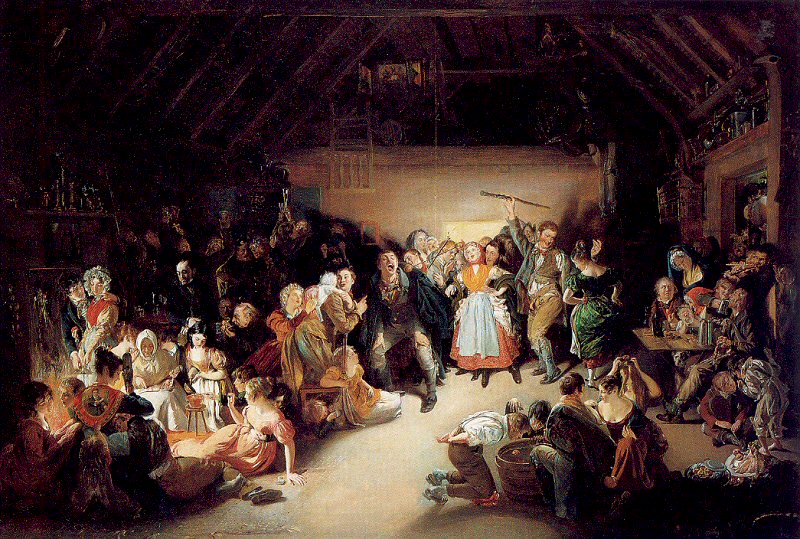

The festival was not always so lighthearted. For the Celts of ancient Britain, Scotland, Ireland, and northern France, November 1 marked the end of harvest, the return of herds from the pasture, the time of what was known in folk wisdom as “the light that loses, the night that wins,” and the start of the new year. It was also the festival of Samhain, who may or may not, depending on the source, have been the god of the dead but who remains a favorite of modern witches, neo-pagans, and fans of Walt Disney’s 1940 film Fantasia. On October 31, the last night of the old year, spirits of the deceased were thought to roam the land, visiting their loved ones, looking for eternal rest, or raising hell. They particularly liked to wreak havoc on crops. They were also capable of revealing future marriages and windfalls, and illnesses and deaths. It was incumbent upon the living, therefore, to welcome them home with food and drink, to propitiate the grudges they might still be carrying, or to light bonfires and carry lanterns made from hollowed-out turnips carved into frightening faces to keep them away. The bonfires also came in handy for immolating vegetable, animal, and human sacrifices to Samhain. In other words, anything might happen on this hallowed night, or, given the sketchy state of modern scholarship about ancient Druid practices, we can easily imagine anything happening. Most accounts of the Celtic origins of Halloween, including this one, should be taken with a pumpkin seed of skepticism. About all we can be certain of is that some festival marked the onset of the long, cold northern winter when living conditions grew raw, food was scarce, and many died.

By the first century A.D., Rome had conquered Celtic lands, Romans and Celts were living cheek-by-jowl in small villages, and Pomona, the Roman goddess of orchards and the harvest, whose festival was celebrated on November 1, was cohabiting happily with Samhain. But if the Romans, who associated Pomona with