Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

May 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 3

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

May 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 3

Editor's Note: David O. Stewart has published five books of American history, including studies of Presidents George Washington, James Madison, and Andrew Johnson, and is a frequent contributor to American Heritage. His fifth historical novel, The Burning Land, is due this spring and follows the Civil War and postwar experience of a soldier in the 20th Maine Infantry regiment. While we do not typically publish footnotes, we have included them for this essay to help readers and future researchers.

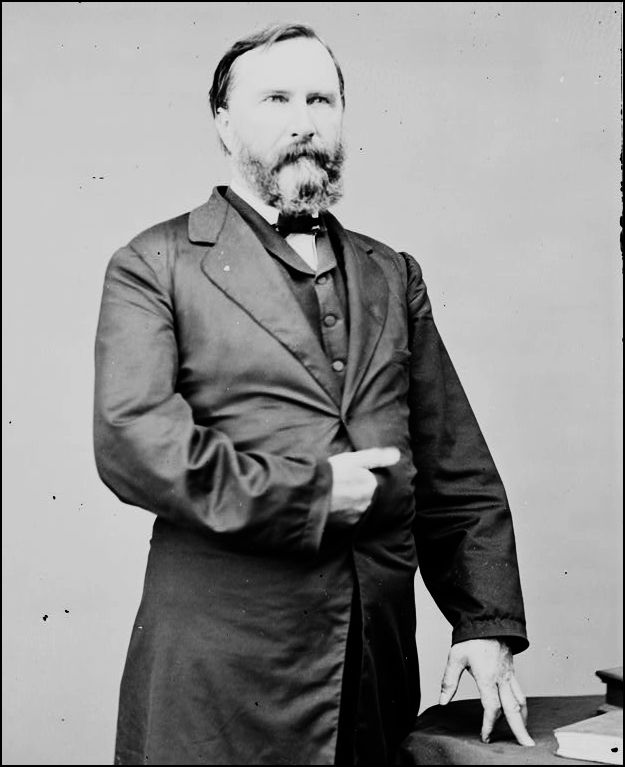

At the fiery battle of The Wilderness in early May 1864, a minié ball slammed into the shoulder of Gen. James Longstreet and burst out his throat. Blood gushed from the general’s neck as comrades took him from the field.

A West Point graduate, Longstreet knew combat. He had suffered a thigh wound in the United States invasion of Mexico in 1847. As a long-serving corps commander in the Army of Northern Virginia, Longstreet faced death in most of the battles in the Civil War’s eastern theater, plus two western campaigns. He saw men die by the thousands, observed gaping wounds and smashed bodies, and viewed acres of corpses.

Yet, after The Wilderness, something snapped inside Longstreet. One woman who attended him during a lengthy recuperation noted that the general “is very feeble and nervous. . . He sheds tears on the slightest provocation and apologizes for it. He says he does not see why a bullet going through a man’s shoulder should make a baby of him.”

After five months, Longstreet’s emotions settled enough for him to return to active duty, though his right arm would always remain paralyzed and he never would again raise his voice above a hoarse whisper.

Two years before, a corporal from Michigan, John Hildt, lost his right arm in the Seven Days Battle in Virginia, then was confined to the Government Hospital for the Insane, suffering from “acute mania.” He remained there until his death forty-nine years later.

Civil War soldiers on both sides endured horrors. Their chances of dying in uniform have been estimated at one in four; that risk for U.S. soldiers in the Korean War was 1 in 126. The psychic strains were many and recurring: fear of rampant disease and determined enemies; grisly scenes of violent killings, dismemberments, even decapitations; handling dead bodies or killing another human, which many found odious. Those pressures led to madness and suicide among soldiers like Georgia infantryman John Williams, General Philip St. George Cocke of Virginia, and Captain Thomas Pickens Butler