Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 2

Editor's Note: Linda Hirshman is a lawyer, cultural historian, and author of several books. Portions of the following essay appear in her latest work, The Color of Abolition: How a Printer, a Prophet, and a Contessa Moved a Nation, which chronicles the fascinating alliance between the abolitionists Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Maria Weston Chapman.

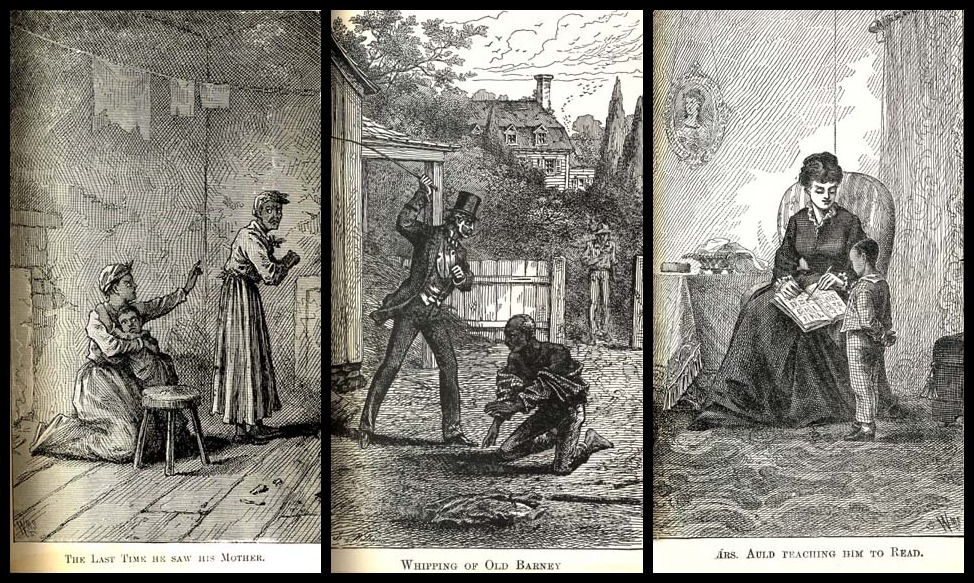

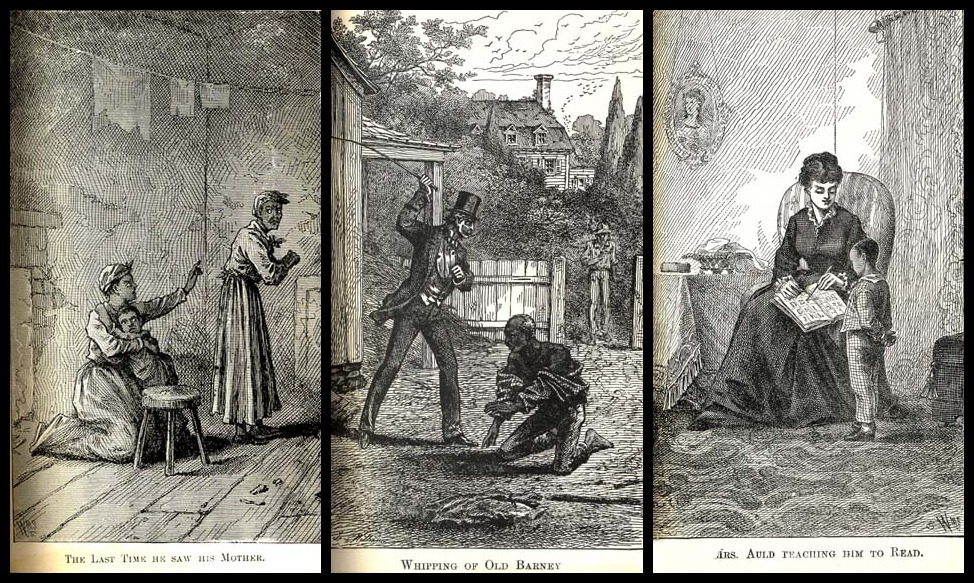

“It is a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away,” Frederick Douglass begins his Narrative, “to part children from their mothers at a very early age.”

When Douglass’ mother was sent twelve miles away to work for another planter in 1819, he couldn’t have been much more than a year old. He never knew his father, who he’d heard was “a white man.” There was talk that the man was his enslaver, but of this, he says, “I know nothing; the means of knowing was withheld from me.” Douglass was lucky enough in his early years to be sent to his mother’s mother to be raised until he was old enough to be of use. During his years as a slave, he was called by his mother’s surname, Frederick Bailey; he named himself Douglass later, after he escaped. She did not live long after their parting, but he was “not allowed to be present during her illness, at her death, or burial.”

The master’s enslaved children were, Douglass astutely notes, “a constant offense to their mistress.” The master had to mollify her by treating them worse, beating them more often, and selling them to the “human-flesh mongers” who traded in slaves. Indeed, Douglass writes, the masters often acted more kindly in selling their children than in keeping them, because keeping them meant beating their own slave offspring or having their children’s white half brothers do the cruel deed to their own siblings.

Douglass had been so completely separated from his mother that he “received the tidings of her death with much the same emotions I should have probably felt at the death of a stranger.” In his second telling of his story ten years later, however, Douglass places his mother in a heroic narrative. He remembers what she looked like, he says; she resembled a drawing “in ‘Prichard’s Natural History of Man.'” Her visits to him “were few in number, brief in duration, and mostly made in the night. The pains she took, and the toil she endured, to see me, tells me that a true mother’s heart was hers, and that slavery had difficulty in paralyzing it with unmotherly indifference.”