Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 5

Authors: Richard B. Frank

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 5

The most basic fact about the Asia-Pacific War is that Japan alone controlled when it ended.

Thus, the sharpest lens for understanding and judging these events is through the viewpoints of key Japanese leaders. American leaders figure in this story, but in an ultimately supplementary role. The military and diplomatic tools which the US did or did not apply all aimed to convince the Japanese leaders that the war must end.

There is one other critical constituency — the dead. The war that Japan officially launched against China in 1937 and prosecuted relentlessly for eight years resulted in approximately two million deaths of Japanese soldiers and sailors, and as many as 1.2 million of the nation’s civilians. Among its enemies, perhaps as many as four million servicemen died, overwhelmingly Chinese. But, by far, the greatest toll comprised civilian deaths in the nations attacked by Japan.

By a conservative accounting, this included twelve million Chinese between July 1937 and August 1945. Additionally, close to six million other civilians were killed between December 1941 and August 1945, notably at least 2.7 million people of what is now Indonesia and at least a million Vietnamese who starved to death in 1945 because Japan had both stolen huge portions of the country's rice crops, and destroyed much else so as to replace the rice with peanut plants to extract oil for its war machine. During that period, the death toll amounted to 8,000 per day among civilians who were not Japanese, or 240,000 per month. That is the combined Hiroshima and Nagasaki death toll, immediate and over time, every month, or that same toll every 1.5 months, depending on the figures you accept for Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The backdrop to events in 1945 is mass death, overwhelmingly of people who were not Japanese.

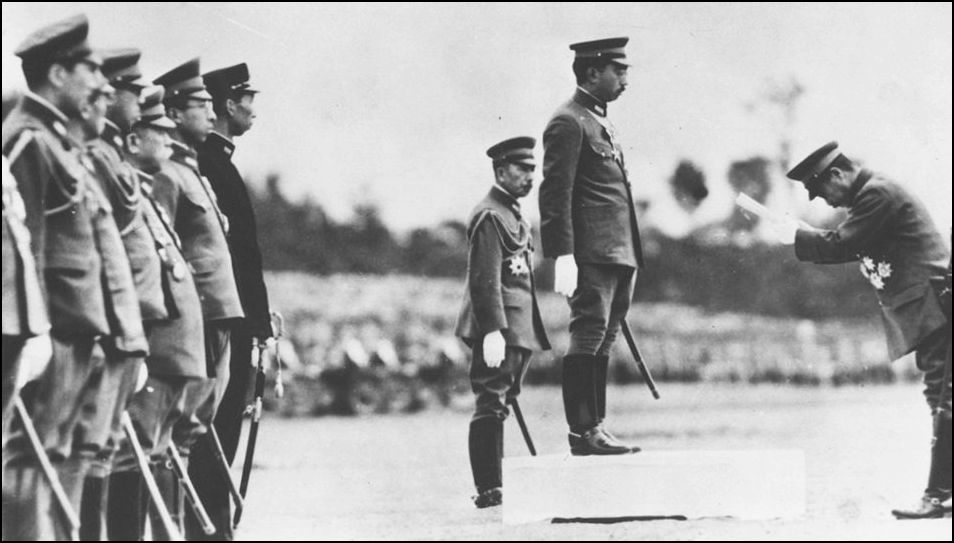

To the outside world, imperial Japan presented Emperor Hirohito as the nation’s supreme and divine ruler. In person, he was slender, bespectacled, and reserved. His father, Emperor Taisho, ended his reign insane. His mother, the dowager empress, believed that his younger brother, Chichibu would make a much better monarch. In 1921, when he was 20, as crown prince, Hirohito broke free from his diligent preparations for his destiny with ostensibly unfettered powers by going on a tour of Europe. The British model of a democratic monarchy of limited powers deeply impressed him.

He proved a keen student of ancient and modern history, both Japanese and international. The most salient lesson he internalized on his role as emperor was the duty to preserve domestic order. In the 1920s, he viewed favorably the new world order following the World War I peace settlement and the Washington naval arms agreements aimed at fostering international cooperation. By the 1930s, he pivoted and viewed accommodation as antithetical to Japan’s interests.

Showa Tenno (emperor in the era of "shining peace"), as he was officially named, found solace and escape from his birthright burdens in carefree hours as an amateur marine biologist. These simmering contradictions in his formal duties and his own perceptions of his role played out in 1945.

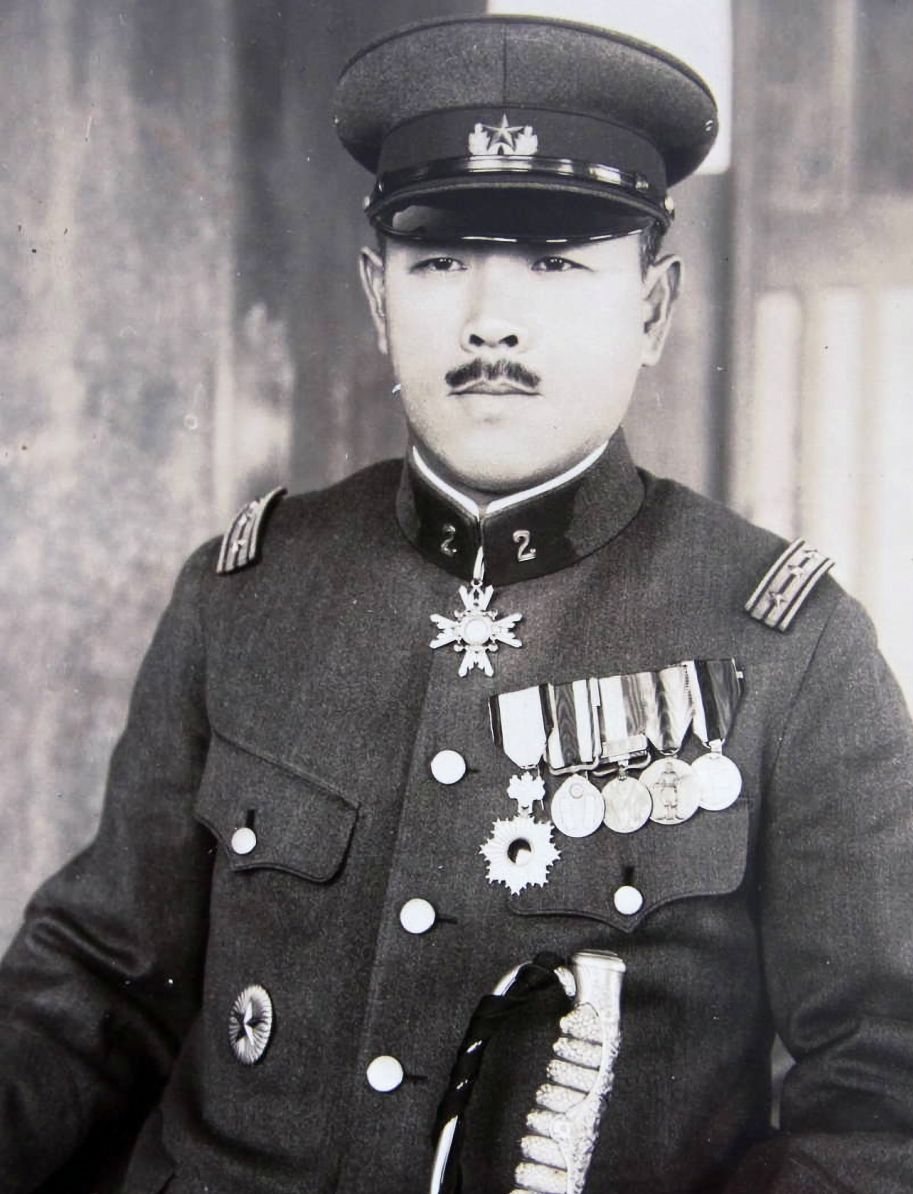

Most importantly, Hirohito, with the six members of an inner cabinet of the government (officially the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War, but known in shorthand as The Big Six), comprised the tiny band who had final authority over when and how the war ended — if it did. These seven men sat atop the most dysfunctional political and military decision-making system among the major World War II combatants.

While the Meiji Constitution of 1889 made the emperor the supreme political and religious leader, in practice, he was insulated from personal responsibility for national policy so as to preserve his aura of infallibility. Hirohito’s exchanges with his senior civilian and uniformed officials demonstrate that he was intelligent, well-informed, and could pose shrewd challenges to their policies. But ultimately, he presided, not decided. Repeatedly, the emperor urged actions that his theoretically subordinate officials ignored — most notably, several imperial army and navy officers.

But the Meiji Constitution’s most baleful provision made the armed forces subordinate to the emperor, and not to the civilian government. Eventually, both military branches gained the right not only to appoint their respective ministers to the cabinet, but the legal requirement that, if either of those figures resigned, the civilian government would collapse. Thus, the armed forces exercised veto power over any government and its policies — including surrender.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Westerners characterized Japan’s political system as “government by assassination.” Between 1921 and 1936, uniformed killers, or their civilian supporters, struck down two prime ministers who dared to violate the

A final stranglehold was that this all-powerful inner cabinet of six men could only adopt a policy by a unanimous vote. At the crucial time, the Foreign Minister, Shigenori Togo, was the sole civilian; all the others were current or former admirals and generals. Thus, ending the war required breaking the Japanese armed forces’ monopoly over Japanese decision-making.

In January 1945, Japan faced an utterly bleak strategic situation. The surface fleet and submarine force had been reduced to near impotence. Allied air power massively outmatched the Japanese, both quantitively and qualitatively. Germany’s defeat loomed in sight. This would unleash its array of far more powerful enemies to focus all their efforts on crushing Japan. The nation's war economy sputtered towards collapse.

No wonder one powerful narrative of subsequent events is “the delayed surrender.” This line maintains that Japanese leaders should have surrendered in January, as that would have spared the nation the overwhelming majority of the civilian deaths it sustained in the war. At least 95 percent of those deaths occurred in 1945 due to the Battle of Okinawa and then the incendiary and nuclear attacks by America (not to mention the far-more-massive number of deaths among those whom Japan had attacked). From August 1945 through 1947, while in Soviet captivity, 340,000-440,000 Japanese civilians died.

From the viewpoint of other Asians, the idea that the Americans bore the greatest responsibility for events after January 1945 is an absurdity. The focus on US actions, while omitting any mention of the deaths of millions of Asians before and after January 1945, casts Japan as the great victim, rather than the great perpetrator.

But Japanese leadership, dominated by the Imperial Army and Navy, resolved to continue the war. The touchstone of their outlook was that, however materially powerful the US might be, its people and ultimately

Deadly-accurate Japanese operational and tactical planning bolstered its overall strategic vision. The Japanese commanders deduced that the US would occupy Okinawa by mid-1945, and that an invasion of Japan's home islands must fall within US fighter-plane coverage from there. A simple map calculation identified southern Kyushu as the most likely target. A quick glance at a topographic map of that main island disclosed the locations of existing or potential air bases. These bases, and the naval anchorage at Kagoshima Bay, would be the objectives of the American landing to secure such sites for further operations on the mainland.

A huge buildup of ground and air forces followed. By mid-year, this totaled between 700,000 and 900,000 men on Kyushu. They formed fourteen divisions and ten brigades. By conserving existing aircraft, pursuing new production, and reassigning training aircraft to the kamikaze role, the Japanese assembled a fleet of 10,000 planes, about half of which were kamikaze craft.

One other preparation carried dire portents. In March, the government announced that all Japanese males from age 15 to 60 (who were not already in the armed forces) and all Japanese females from 17 to 40 were to be members of a gigantic national militia, mobilized for the final battles. This made it virtually impossible to distinguish combatants from civilians in Japan.

The Japanese christened their strategy Ketsu Go (Operation Decisive). It had two sequential components. The first would be the counter-invasion battle. This would gain the negotiating leverage that Japan lacked. There was no need - in fact it would be premature - to formulate negotiation terms before the military component created the necessary leverage. This basic point is the key to understanding how the Japanese armed forces navigated 1945.

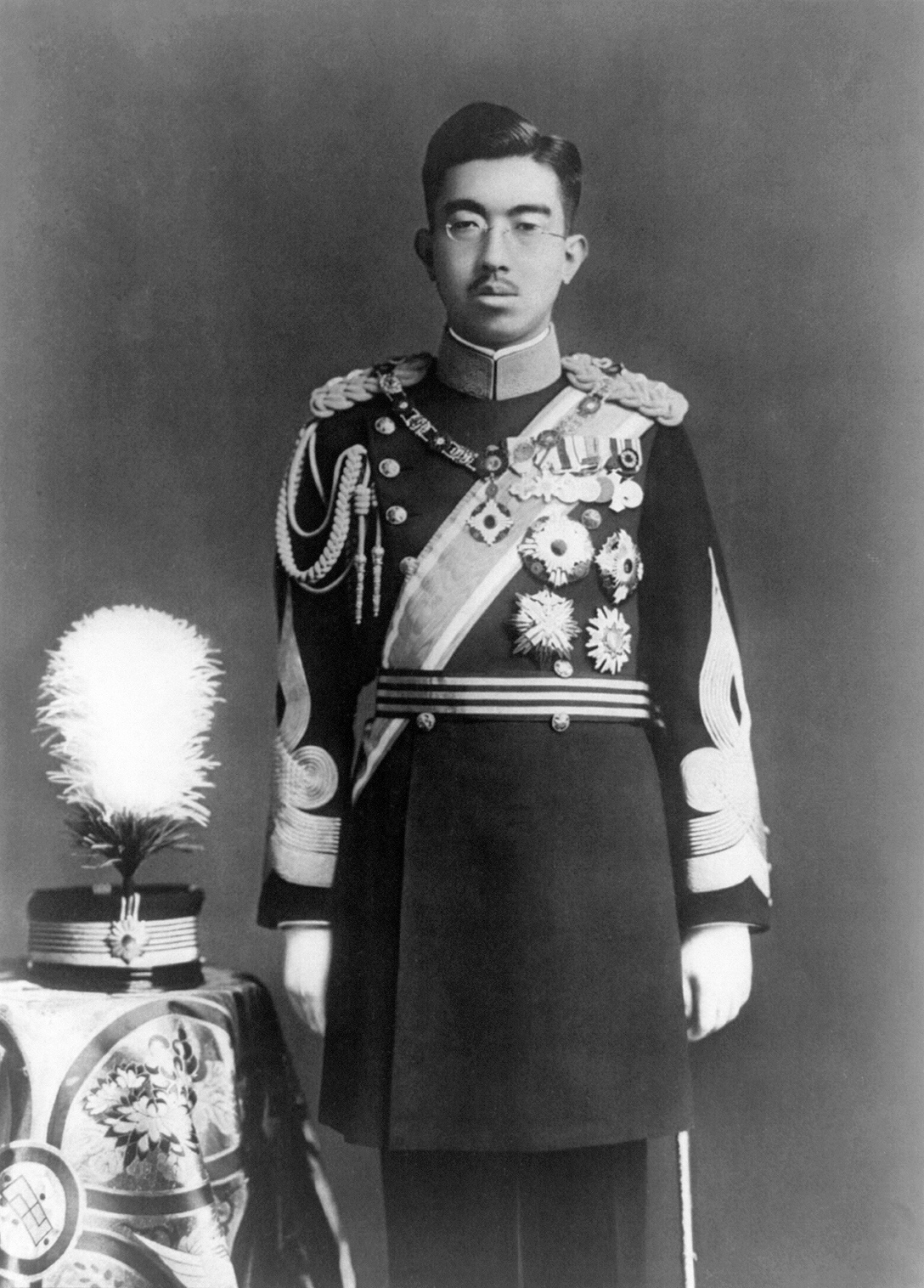

When the government of Prime Minister Suzuki Kantaro came to power in April, General Anami Korechika became the War Minister, the “most influential and powerful man in

Above all, Anami personified the ethos of the Imperial Army: spiritual power would surely triumph over mere material power. His subordinates adored him, yet his loyalty to the emperor, sealed with his tour as the military aide to the throne, foretold the divided loyalties that would play out in August.

Roosevelt set the national war aim in 1943 as the “unconditional surrender” of the Axis powers. This term assumed the absolute defeat of Italy, Germany, and Japan, followed by occupation and fundamental reform to assure an enduring peace. Lawyers advised American occupation planners that “unconditional surrender” afforded far more scope for reform than the existing international law of military occupation. Indeed, “unconditional surrender” left no clear outer boundaries for reform. “Unconditional Surrender” thus was not merely a slogan for victory, but the foundation for an enduring peace.

Devising a strategy to achieve “unconditional surrender” fell to the body later formally known as the Joint Chiefs of Staff. They first doubted the prospects of “unconditional surrender.” No Japanese government had surrendered to a foreign nation in Japanese history (by Japanese count, 2,600 years) and no Japanese unit had surrendered in the whole war. It was not clear that a Japanese government would surrender, or, even if one did, whether the armed forces would comply. This defined the ultimate American nightmare: not just an invasion, but the prospect of a protracted struggle in Japan and wherever Japanese forces awaited. As the Joint Chiefs warned, there would be “no alternative to the annihilation” of Japanese forces in Japan, on the Asia continent, or in the Pacific.

Ultimately, the Joint Chiefs produced an unstable compromise on strategy that reflected a fundamental divide between the army and navy. A political issue created the split: what strategy was most likely to undermine the will of the American people to see the war through to “unconditional surrender.” General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the Army, saw time as the critical matter. A protracted final struggle would likely dissolve American will. Therefore, the army advocated invasion as the quickest means to end the war.

The Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest J. King, trim and famously tough, was a far-sighted strategist and expert bureaucratic combatant. He channeled the bedrock navy doctrine, evolved over decades of study, that invading Japan would be unmitigated folly. The US could never project an expeditionary force to Japan’s shores that would outmatch its millions of defenders, and, in the main, a fanatically hostile civilian population. The inevitable outcome of invasion would be politically

The naval doctrine thus advocated a strategy of bombardment (by ship and plane) and blockade. For centuries, naval blockades formed a standard fixture of naval strategy, but always under the law and customs of warfare that forbade preventing the passage of food to civilian populations. In World War I, the British and the Germans both threw out that restraint, and at least a half million Germans starved to death. This produced an internal revolt that was the primary cause of the German surrender in 1918. The US Navy resolved to follow that example against Japan. Thus, the navy’s preferred strategy looked to end the war by starving to death enough Japanese (millions, overwhelmingly civilians) to produce a capitulation.

In April 1945, the Joint Chiefs formally adopted a strategy to end the war with Japan. It aimed to continue the still-gathering efforts at bombardment and blockade, and then add the invasion, set to begin on November 1, 1945, of southern Kyushu (Operation Olympic). This was exactly as the Japanese anticipated. The famously taciturn Admiral King distributed a memorandum to his colleagues announcing that he only supported ordering the invasion so as to have that option in the fall. He predicted that the Joint Chiefs would actually have to come back to authorize an invasion in August or September.

At this point, none of the top US leaders saw atomic weapons as sure to be ready soon. As historian Barton Bernstein shrewdly observed, from the start of the Roosevelt’s atomic-weapons program, the assumption was that, if a bomb could be developed, it would be used. Because Roosevelt never fully addressed the actual use of atomic weapons, no one could tell Harry Truman — who had pledged to carry out the late president’s legacy -- if Roosevelt would have broken that momentum.

Deeply disturbed by the specter of the costs of Operation Olympic, President Truman summoned a meeting of his key advisors. The memorandum calling the meeting stated that the president’s principal criterion was casualties. At the June 18 meeting, General Marshall led off by advocating the invasion. King’s apparent support for Marshall was artfully hedged. He said that any invasion authorized then could be canceled later. During a broad but not deep discussion, at least four different projections of casualties were shared with Truman. All these projections would become moot in five weeks. Faced with the unanimous support of all his advisers, Truman authorized Operation Olympic.

Several Japanese diplomats and attaches in Europe approached American officials, claiming to represent Japan to explore the possibility of peace negotiations. Massive decryption of the Japanese diplomatic radio traffic generated by an electro-mechanical cipher revealed that not one of those men enjoyed the official backing of the Japanese government. This was passed on in the daily newsletter, called the “Magic” Diplomatic Summary, distributed to a very select group of American officials, starting with Truman. (The “Magic” code name came from a former chief of

For nearly the first half of 1945, Hirohito supported Ketsu Go. Then, inspectors he had dispatched reported large deficiencies in preparations for the vital counter-invasion battle. Former Prime Minister Konoe urged him to breathe life into the feeble approach to negotiations in order to secure Soviet mediation to end the war. The upshot appeared in a July 13 message intercepted by “Magic” disclosing that the emperor was pressing for a diplomatic initiative to secure Soviet mediation. The channel would be the Japanese ambassador in Moscow, Naotake Sato.

Polished and assured, Sato was a former foreign minister, and was a sophisticated figure in the small circle of men who participated in critical decision-making, but he was not one of the final deciders. He performed officially as the vital conduit for Japan’s only authentic diplomatic demarche towards possible negotiations to end the war. But, effectively, he served as the prosecuting attorney for the Truman administration, in that he actually wrote a searing demolition of feckless Japanese diplomacy. The ambassador focused laser-like on two basic issues. First, Japan must present substantive concessions to obtain Moscow’s services as an intermediary. Foreign Affairs Minister Togo struggled with this demand because the Big Six could never agree even on such concessions. He contrived verbiage to meet that basic requirement, but Sato’s blunt rejoinder condemned his letter as “pretty little phrases devoid of all connection with reality.”

Then, Sato stabbed a rapier into the heart of the initiative: Moscow’s ultimate test of genuine Japanese intentions hinged on specific Japanese terms to end the war. Sato’s demands also presented American officials with a litmus test of Tokyo’s intentions. According to Admiral and Navy Minister Mitsumasa Yonai, the Big Six had attempted to discuss actual terms prior to Hiroshima only one time. This discussion collapsed immediately when War Minister Anami declared that he would only discuss terms on the premise that Japan had not lost the war. Thus, Togo could not answer Sato’s repeated demands for terms.

Exasperated by Togo’s evasions, Sato bluntly informed him that the only terms Japan could obtain would be “unconditional surrender,” modified solely to the extent of preserving the imperial institution. Togo’s reply on July 21: "That is totally unacceptable." He did not even suggest that an offer to preserve the imperial institution would be a step in the right direction for the Japanese government.

A central pillar in challenges to American policy-making in 1945 is that Japan’s leadership would have ended the war if it had just been presented with an offer to preserve the imperial

Events now moved at lightning speed.

Heavy domestic pressure on the Truman administration demanded some effort to define “unconditional surrender” in a fashion that might induce a surrender. The Germans in May had effectively signed a blank check: their “unconditional surrender” document contained no defined terms whatsoever. Now, administration figures – notably, Secretary of War Henry Stimson - drafted a note containing multiple pledges which the Germans never received, such as democratic reforms and a promise that the Allies would hold Japan’s leadership responsible for the war, but not ordinary citizens. This appeared against a backdrop following German surrender in which the Soviets' ethnic cleansing of German enclaves in eastern Europe had resulted in at least a half million German deaths.

What to do about the imperial system and the emperor himself emerged as the critical controversy. Stimson’s draft took the form of a stern ultimatum, but it incorporated a specific proviso that, ultimately, the Japanese people would choose their own form of government, and that this might include a member of the existing imperial dynasty. When the Joint Chiefs reviewed the draft, they warned that Stimson’s language regarding the imperial dynasty included dangerous ambiguity. The Japanese could read this as promising the continuation of the imperial system, or perhaps that the US was already committed to executing Hirohito or deposing him and replacing him with another member of the imperial household.

The military chiefs felt that both interpretations would be perilous: one, a nullification of “unconditional surrender” and its foundation for reform, and the other, a godsend to Japanese diehards. In its place, the Joint Chiefs advocated language that became the final relevant term in the July 26 Potsdam Declaration: “The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan as soon as these objectives (demilitarization and democratization, foremost) have been accomplished and there has been established, in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people, a peacefully inclined and responsible government.” This presented no prohibition on continuance of the imperial institution or Hirohito if that reflected “the freely expressed will” of the Japanese people.

Later critics argued that Japan rejected the Potsdam Declaration because it was too severe and contained no pledge to retain the imperial system or even Hirohito’s place on the throne. In reality, the amended clause backfired and bolstered the faith of the Big Six

The unilateral American concession of multiple terms, which the Germans had never obtained, appeared to those men in Tokyo as only a foretaste of the far more vital concessions which a counter-invasion bloodbath would lead to. If two-thirds of the “moderates” interpreted an emphatic vindication of Ketsu Go from the Potsdam Declaration, there can be no reason to suppose that it was not viewed the same way by the “hardliners,” from the American viewpoint (namely, War Minister Anami and Chiefs of Staff Yoshijiro Umezu and Soemu Toyoda).

But, as the US diplomatic strategy played out, shocking intelligence struck a stunning blow regarding Operation Olympic. Original estimates anticipated just six Japanese divisions on Kyushu and only three in the south of the island, where the initial landing was planned. General Marshall had allowed that the Japanese might forward reinforcements after the landing, but that they would arrive piecemeal. The total Japanese forces eventually assembled might reach 350,000. The American landing force numbered about 770,000 men in thirteen divisions and the equivalent of another division in regimental combat teams. American forces would also have a huge majority in ground, air, and naval firepower over the defenders. This promised a marked superiority in combat power over any defenders the Japanese could muster, and victory at an acceptable cost.

But, starting on July 9, radio intelligence began unmasking the huge Japanese buildup exactly in the planned invasion areas. By July 25, one intelligence officer said that the US would be going in at a “a ratio of one to one” (attacker to defender) and “this was not the recipe for victory.” The number of projected defenders, most in place at the time of the landing, was more than 600,000 (about ten times the original estimate for the landing date), and most of the major Japanese units were identified and positioned in the proposed landing areas. Anyone with merely modest command of military realities would recognize that Operation Olympic promised to be a horrendous bloodbath. This is why citing earlier casualty estimates to disparage the honesty of post-war claims regarding fears of massive losses are totally out of context. American leaders were actually seeing events in the later half of July and early August that completely upended any prior estimates.

This radically-changed invasion outlook shocked General Marshall. He sent a cable to Douglas MacArthur, the senior Army officer in the Pacific and the designated commander of Operation Olympic. In light of the new intelligence, Marshall asked whether MacArthur still supported Olympic. MacArthur replied that he did not believe the intelligence and that he remained determined to launch Olympic.

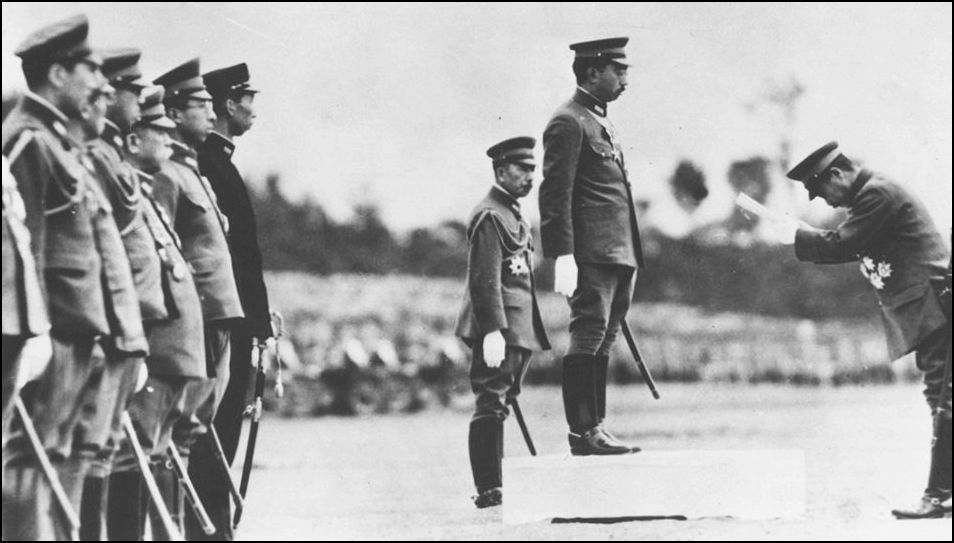

Admirals Raymond A. Spruance, Ernest J. King, and Chester W. Nimitz, and General Sanderford Jarman (left to right here, at Saipan in 1944) that an invasion of the Japanese mainland would be a disaster. U.S. Navy" data-entity-type="file" data-entity-uuid="1507ee67-6ae1-472e-bb5d-3244dd4a5b2a" src="https://www.americanheritage.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/Spruance%2C%20King%2C%20and%20Nimitz.jpg" width="1028" height="682" loading="lazy">

Admiral King pounced. He knew that the facts now aligned in support of his iron determination to avoid any invasion of Japan. He took the exchange between Marshall and MacArthur and included it in a message to Admiral Chester Nimitz, the senior naval officer in the Pacific and for Olympic. King asked Nimitz for his “views.” But Nimitz, back in the end of May, had privately informed King, without telling the army, that he could no longer support any invasion of Japan. Nimitz explained that the ferocious fight on Okinawa, a stunning preview of an invasion of the Japanese home islands, had triggered his new view.

Then, within twenty-four hours of this message, King warned Nimitz that the Japanese might be seriously seeking peace. Keenly aware that a message rejecting any invasion would probably ignite the single most rancorous inter-service debate of the war, Chester Nimitz paused. His hopes that events might release him from this obligation were realized.

The wartime taboo prohibiting public acknowledgement of radio-intelligence feats seamlessly merged into the post-war “Ultra Secret” classification black hole. Many decades passed before disclosures emerged not only involving the radio intelligence itself, but of records that discussed that intelligence. Thus, the revelation that the Navy sought to scuttle Operation Olympic in the face of evidence of a Japanese strategic ambush on Kyushu and Ambassador Sato’s demolition of Japanese diplomacy only appeared belatedly, long after narratives oblivious of these critical facts had beome entrenched. Because Truman and his subordinates rigorously held their silence on radio intelligence, they forfeited the most cogent evidence which explained and supported their decisions.

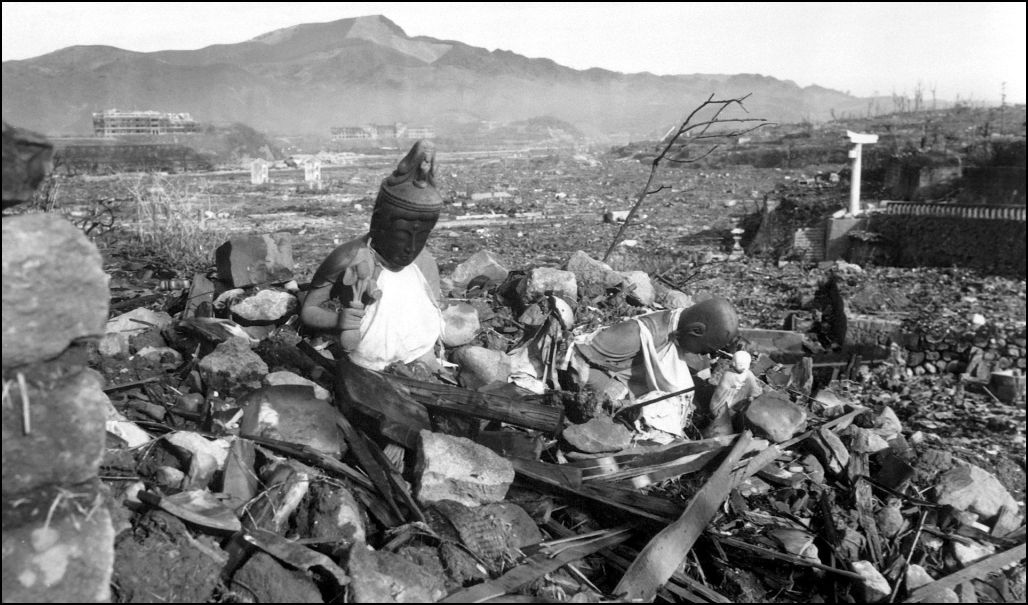

On August 6, the B-29 Enola Gay dropped “Little Boy,” the nickname for the first atomic bomb created, 1800 feet over Hiroshima, for maximum destructive effect. The full magnitude of the devastation and slaughter did not break through to Tokyo until the next morning with a message from the Imperial Army Vice Chief of Staff: “The whole city of Hiroshima was destroyed instantly by a single bomb.”

Government radio monitors reported Harry Truman’s public announcement that an atomic bomb had struck Hiroshima. The leaders of the Imperial Army insisted that the existence of an American atomic bomb must not be conceded without an investigation. But the Chief of the Naval General Staff, Admiral Toyoda argued that the US could not possess more than a limited amount of fissionable material (essential to making an atomic bomb), and which could only produce a few bombs. Further, he thought that international opinion might persuade America to stop

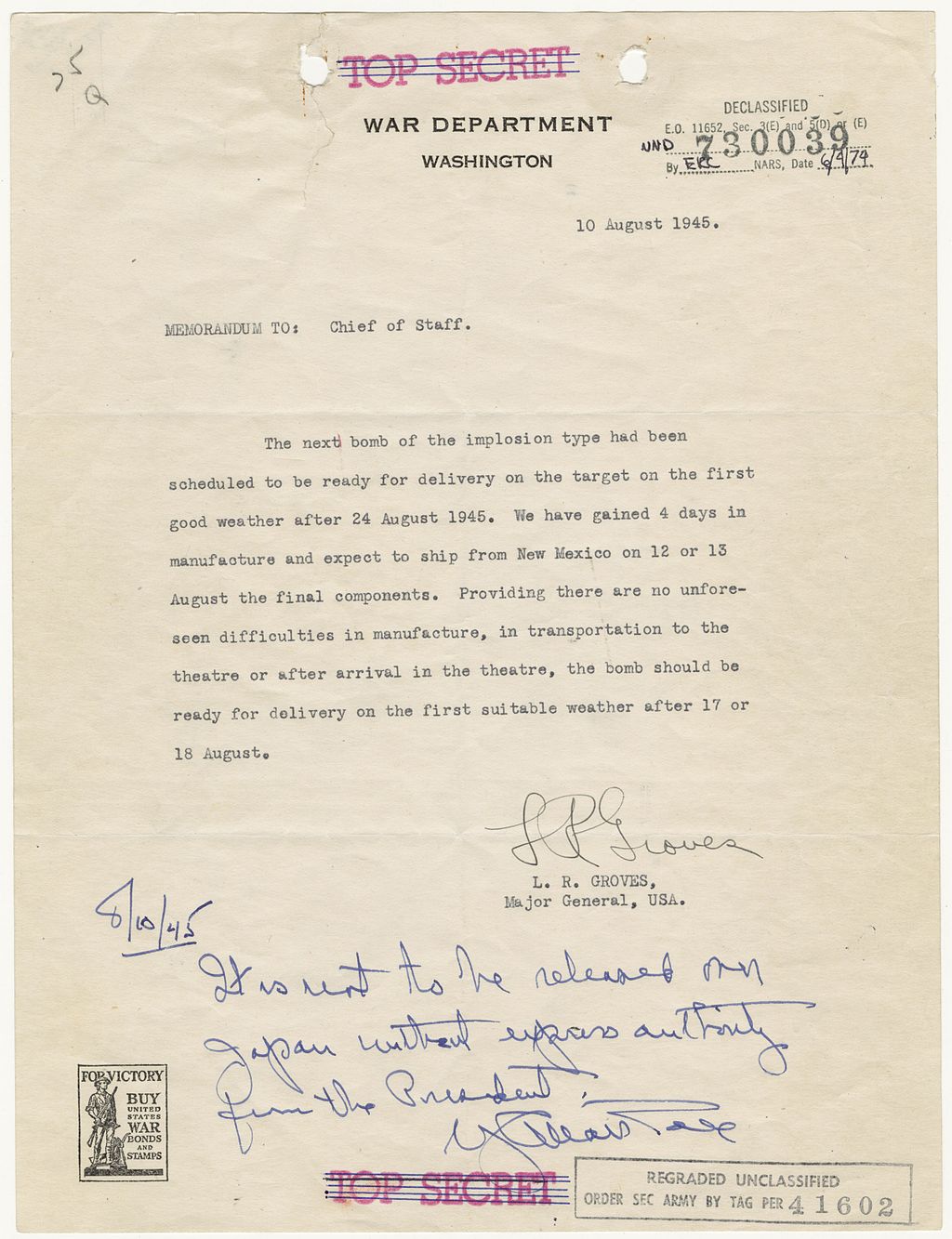

These responses stemmed from Japan’s own atomic bomb program. That effort produced no bomb, but it did equip the top leaders with the knowledge that producing fissionable materials was a very costly and protracted enterprise. This tells us that no demonstration of a single bomb would have been effective. The Japanese response to one demonstration would have been something like: “Very interesting. Let’s see two (or more) in a row.” It also confirmed the prescience of leaders like General Leslie Groves, the head of the Manhattan Project that built the bombs. He insisted that it would require two bombs to end the war - the first to establish the existence of an American bomb and the second to imply (read: bluff) that the US immediately had an arsenal of such weapons. There were actually only two or three bombs available in August 1945.

The Hiroshima bomb did galvanize one Japanese leader. Lord Marquis Kido, officially the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, but in fact, Hirohito’s closest confidant, advised the emperor that an atomic bomb had inflicted “extremely serious damage” on Hiroshima and 130,000 casualties. On the afternoon of August 8, Hirohito met with Foreign Minister Togo. They conversed in a new bomb shelter which the emperor learned he had been escorted to for the first time because it was thought to be more resistant to an atomic bomb. Hirohito said that the “new weapon” made it “less and less possible to continue the war.” He ordered Togo to “do his best to bring about an early termination of the war.”

The Imperial Army fended off Togo’s effort to convoke an immediate assembly of the Big Six until the morning of August 9. During the night before, the Soviet Union launched a massive campaign to overrun Japanese-held Manchuria. News of this attack had arrived before the meeting, but the initial reports were sketchy, and they grossly understated the magnitude of the Soviet onslaught. The Japanese Kwangtung Army in Manchuria was in a relatively lame state because its array of first-class units had been stripped away to face the American Pacific thrust; the last quality divisions had shipped to the homeland for Ketsu Go. Imperial Headquarters that morning received reports of the shattering effects of air raids on public morale in the medium-sized and smaller cities, causing near panic in some locales. The Vice Chief of the Imperial Army, General Torashiro Kawabe, wrote in this diary that news of the Soviet intervention was a greater shock to him than the Hiroshima bomb. But he insisted that the Imperial Army must answer this situation by abolishing any vestige of civilian government, and proceed to rule Japan through Imperial Headquarters. War Minister Anami endorsed this plan.

As the Big Six met, news came of a second atomic bombing at Nagasaki. Under its procedures, the supreme war council could only approve a

The “hardliners” (Anami and the Chiefs of Staff Umezu and Toyoda) insisted on three more conditions: 1) Japan would disarm its own forces; 2) Japan would conduct “war crimes” trials (called for in the Potsdam Declaration); and 3) there would be no occupation of Japan. Without occupation, Hirohito’s position would be secure and the Allies would lack the access needed to impose reforms. The tie vote proved crucial. The “peace faction” seized upon this to convene an Imperial Conference (one before the emperor), where, for only the second time in his almost two-decade tenure as emperor, Hirohito might impose his will and not just rubber-stamp a policy advanced by his civilian or uniformed subordinates.

The conference began just after midnight. Most of it followed the ritual recitation of the positions of the committee members. Most notably, General Umezu told the emperor that Soviet intervention was “unfavorable,” but it did not negate Ketsu Go. Umezu was correct. The Soviets possessed enormous ground and tactical airpower on the Asian continent, but they lacked the sea lift to transport a huge invasion force to Japan. Finally, Prime Minister Suzuki called on the emperor to provide his decision. Hirohito announced that he endorsed Togo’s proposal. The full cabinet, including the Bix Six, voted to approve the emperor’s recommendation and give it legal standing.

But then, the nascent surrender was imperiled. The Foreign Ministry message stated that Japan had accepted the Potsdam Declaration on the understanding that it did not “prejudice the prerogatives of His Majesty as Sovereign Ruller.” This has been quite wrongly interpreted as only a request to preserve the imperial institution with a “symbolic” emperor. As historian Herbert Bix and various Japanese scholars have made clear, this was a demand to preserve the monarchy and place the emperor in a superior position to the occupation authorities. In other words, it would have made clear Hirohito’s veto power over the occupation reforms.

Fortunately, US State Department officials recognized the true import of this language. The response became known as the “Byrnes Notes,” after Secretary of State James Byrnes. Its key passage stated: “From the moment of surrender, the authority of the emperor and the Japanese government to rule the state shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied powers.” There would be no opportunity for the emperor or the Japanese government to block occupation reforms. This document also repeated the Potsdam Declaration that

Now, Hirohito would have to intervene a second time. Kido’s diary of August 13 confirmed Hirohito’s exact thinking. Even if the Americans wanted the imperial institution to continue, Hirohito explained, it would still be extinguished if it was not supported by the Japanese people. Therefore, he decided that the proper course was to submit the fate of the imperial institution to the Japanese people. In other words, 19 days after the Potsdam Declaration had offered the Japanese people the right to consent to the preservation of the imperial institution with their “freely expressed will,” Hirohito was prepared to place the fate of the that institution on exactly those terms. On the 14th, Hirohito reaffirmed his revolve that Japan must surrender. The Big Six and the government fell in line.

Ultimately, Japanese leaders decided when and how the war ended. First, someone with legitimate authority had to decide that Japan would surrender. The Suzuki government on its own never agreed to surrender. Nor do we know for sure when it ever might have surrendered — assuming that it was not abolished by the Imperial Army following the Soviet intervention. Hirohito thus became that critical legitimate authority. He first articulated his decision to Togo on August 8, before Soviet intervention or Nagasaki. His own words show that the Hiroshima bomb had moved him from the sidelines. In his statement at the imperial conference on August 10, he gave three reasons: First, his loss of faith in Ketsu Go. Second, he cited the conventional and atomic bombings. Third, he spoke of the “domestic situation.”

Over the next several days, Hirohito only identified Soviet intervention once, and that was in conjunction with the atomic bombs. When he wrote a letter to his son, the crown prince and next emperor, which he never expected to become public, he likewise made no reference to the Soviets. He said that the Japanese had regarded the British and Americans too lightly and had excessively and irrationally exalted fighting spirit, while ignoring “science,” which, by then, was another euphemism for atomic weapons.

On August 15, in his radio broadcast to the Japanese people, Hirohito admitted that “the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage.” This was in deference to General Anami, who committed suicide rather than betray Hirohito over the surrender decision. That line went almost wholly unrecognized as a covert claim for history that Ketsu Go might have worked. Then, Hirohito intoned that “the general trends of the world have all turned against our interest. Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is indeed incalculable, taking the

Not only did the emperor never use the word “surrender” in this broadcast; he presented Japan’s decision as a noble sacrifice to save the world from destruction and lead it to a great peace. There was no direct reference to Soviet intervention, nor any acknowledgement of the loss of millions of “innocent lives” of civilians who were not Japanese at the hands of Japan’s military and scientists.

Starting with a small number of critics immediately during and after August 1945, by the mid-1960s, a major historical controversy had erupted over what motivated the emperor and the armed forces to surrender. But, from the beginning, virtually all sides erred by myopically reducing the key causes of the surrender to just two: atomic bombs or Soviet intervention.

This is baffling, as, from the beginning, the emperor and many other important Japanese figures spoke of a third contender: the “domestic situation.” Historian Noriko Kawamura argues cogently from mostly long-available evidence that it was the central factor in Hirohito’s decision to end the war. This analysis properly emphasizes that, from at least July onwards, Hirohito returned to the touchstone of his role as trustee of the imperial institution, and the obligation to preserve it as his highest duty. The notion that the imperial institution would forfeit its legitimacy in the eyes of the Japanese people loomed as more disturbing to him than even surrender and occupation.

The bland term “domestic situation” camouflaged the stark terror among civilian and military leaders that even the incredibly loyal Japanese people were reaching an intolerable state of desperation. Foremost was the daily, all-consuming search for food. It produced massive absenteeism from military and other factories. Food shortages and air raids led to the dramatic depopulation of most cities. In June, an alarming warning reached the leadership that even optimistic projections showed that food supplies would be even more meager in the fall, and that salt would be at the bare minimum for survival. Local famines could be expected, due to the enemy’s actions. Daily, the Japanese people witnessed the stark evidence that their armed forces could not defend the country. The fundamental causes of collapsing civilian morale were the American campaigns of bombardment by air and sea and the blockade.

The so-called Showa Tenno was not alone in his fear of collapsing civilian morale. Former Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, Foreign Minister Togo, and senior army and navy officers shared this alarm. Chief of Staff of the Army Umezu and his deputy General Kawabe both cited collapsed public moral as dictating an end to the war. Navy Minister Yonai flatly called the atomic bombs and Soviet intervention “gifts from the gods” because they would cover up the real reason for surrender: the “domestic situation.”

But Hirohito’s decision would not suffice without the compliance of the armed forces. This is another void in much of the critical literature which simply assumes that, once the emperor made his decision, the armed forces would automatically obey.

Great emphasis has been placed on an attempted coup d’état in Tokyo on the night of August 14-15. The reality is that this hastily contrived effort by a small band of junior-grade conspirators had no real chance of success. They understood that, to have any chance, they must secure the support of the top officers. The lower-ranking "patriots" beseeched War Minister Anami to join them, recognizing that his support almost certainly would guarantee success. After appearing to waiver, Anami placed loyalty to the emperor over his samurai revulsion to surrender. He committed suicide while wearing a shirt given to him by the emperor, symbolizing how he had atoned for his conflicted loyalties.

Far more threatening was the immediate response of two of the three major overseas commanders: General Yasugi Okamura of the China Expeditionary Army and Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi of the Southern Area - basically, Southeast Asia and parts of the Pacific. They flatly informed Tokyo that they would not comply with the surrender. And they commanded between a quarter and a third of all Japanese neb under arms, and were only finally brought into line by the emperor’s personal representatives.

The extremely ill-conceived Soviet attack on the Kuril Islands (north of Japan) with very modest forces (the only kind that a Soviet sea lift permitted) sparked another dramatically tense moment. The Soviets targeted the most obvious island, exactly where the Japanese waited with a mass of defenders. Consequently, the Soviet landing teetered on the edge of defeat on the very first day. The local Japanese commanders ignored orders from Tokyo, even one from the emperor, to cease resistance. For a time, the terrifying specter appeared that a “victory” over the Soviets there would spark an unraveling of compliance with the surrender in the armed forces. No wonder Admiral Yonai told post-war interrogators that his most anxious moments came in the days after the emperor’s decision.

Finally, this brings us back to Ketsu Go. The most diehard Japanese soldiers and sailors staked the nation’s future on the premise that, by defeating or inflicting huge casualties on the initial American invasion forces, Japan could still obtain a negotiated peace that preserved the old order dominated by the hyper-militaristic and nationalistic forces that propelled Japan down a path that was disastrous not only for Japan, but for millions of others.

As Prime Minister Suzuki told American interrogators shortly after the war, this conviction drove the Big Six uniformed members until the atomic bombs were dropped. Little Boy and Fat Man demonstrated that the Americans would not need to attempt an invasion, but would just fall back on bombardment with such devices. If there was no American

Ketsu Go also relegated diplomacy to a secondary status because the scope of a negotiated settlement would be determined by the leverage gained in the counter-invasion battle. Ambassador Sato boldly exposed this fact by forcing Foreign Minister Togo to admit that the most powerful leaders of Japan had never agreed on the concessions needed to secure Soviet intervention, as well as the failure of the "leaders" to formulate any terms to end the war — even rejecting Sato’s proposal that a retention of the imperial institution must be part of a settlement. Far from advancing with a confidence in imminent victory at low or minimal American cost, from the start of 1945, American leaders faced the bleak prospect — as the Joint Chiefs had pointed out in April — that it might not be possible to obtain the surrender of the Japanese government, and even if the government surrendered, Japan’s armed forces might not comply with that decision.

The Joint Chiefs observed that there was no historical precedent for either event. Then, American leaders learned through radio intelligence that the Japanese were not seriously considering surrender via diplomacy in July. By the end of that month, they knew that the contemplated invasion promised to be a nightmare far beyond their worst fears. Without “unconditional surrender,” the occupation reforms to secure an enduring peace would not be achieved. The Potsdam Declaration backfired spectacularly in stoking the resolve of the hardliners to go forward with Ketsu Go, but, in the end, that declaration threw a lifeline to Hirohito, who ultimately enforced his decision to surrender on its promise that the Japanese people could choose their own form of government.

Because of the intransigence — the paralysis — of Japan’s leadership, there was no way to end the war without a horrific loss of lives. Time was death to the masses of civilians who were not Japanese. The cost of the invasions as planned had become unthinkable. The alternative of blockade and bombardment aimed to kill millions of Japanese, mostly noncombatants. Who should pay the costs for ending the war? One cannot coherently maintain that Japanese civilians be spared from harm, while ignoring the mass death of such people who were not Japanese. The logical coherence of placing the lives of Japanese civilians foremost collapses when the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians due to Soviet entry is not even mentioned. There was no cost-free path to ending

When the end abruptly came through a series of highly contingent events, it was, most of all, a terribly tragic and miraculous deliverance. And that is the way we should see it: not to be celebrated, but to be understood as a tragedy with no possible happy outcome. In the end, as Secretary Stimson later stated, the atomic bombs were not the best option, but the “least abhorrent choice.”

If you want to find a celebration of the outcome, look to China, Indonesia, Vietnam, Korea, or any number of other Asian countries. They insist that all their dead be counted and recognized for their common humanity with the Japanese.