Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 1

Editor's Note: Bruce Watson is a writer, historian, and contributing editor at American Heritage. You can read more of his work on his blog, The Attic.

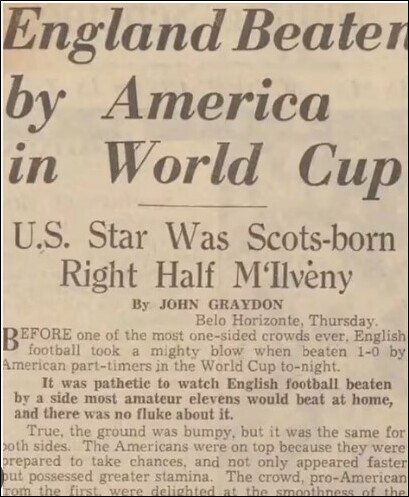

BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL — JUNE 29, 1950 — No eyes of an eager world focused on the soccer squads as they took the pitch that afternoon. But to 30,000 onlookers in this Brazilian mining city, the game looked like it would be a rout.

The British were the “Kings of Football,” 3-1 favorites to win the 1950 World Cup and expected to beat the U.S. (500-1 odds) by six goals or more. Hadn’t the Americans lost recent matches by 4-0, 5-0, 11-0? Weren’t they a ragtag band of amateurs?

Forward Walter Bahr taught high school in Philadelphia. Forward Joe Gaetjens was a dishwasher in Manhattan. The team also included a mailman, a machinist, and a few factory workers. Goalie Frank Borghi, nicknamed “the six-goal wonder” for the average score against him, drove a hearse for a funeral home.

“We were playground players,” one recalled in The Game of Their Lives. “Like the kids you see today shooting baskets in any park.”

But there was a scrappiness about the Americans, noticed by one reporter. “The Americans came strolling into the dressing rooms in Belo Horizonte, surely the strangest team ever at a World Cup. Some wore Stetsons, some smoked big cigars, and some were still in the happy, early stages of hangovers."

In the game’s first twelve minutes, England had six shots on goal. Two hit the post, and one sailed inches over the crossbar. Frank Borghi saved others with a dive, a leap, a prayer.

Then, the Americans brought the ball upfield and took their own shot. England’s goalie gobbled it up, but fans came alive, roaring for the Americans. A minute later, Borghi made another diving save. And another...

Whether you call it football or soccer, it is the world’s game, “the beautiful game.” The grace, the footwork, the endurance endeared it to every country — except America. In 1950, no one in America played soccer. There was no MLS, no youth soccer, few college teams.

So, when the American squad somehow qualified for the cup, the first since 1938 due to World War II, no one cared. The lone American journalist among 400 covering the cup had paid his own way to Brazil.

The exception came in immigrant circles, especially in St. Louis. There, tightly knit enclaves — Germans in Deutschtown, Irish in Dogtown, Italians on Dago Hill — played their hearts out.

“You played for the neighborhood; you played for the