Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2023 | Volume 68, Issue 4

On March 25, 1893, a gala dinner was held in honor of Daniel Burnham, the driving force behind the Columbian Exposition, the World’s Fair about to open in Chicago. Various artists and architects who had worked on the project gathered for this lavish event.

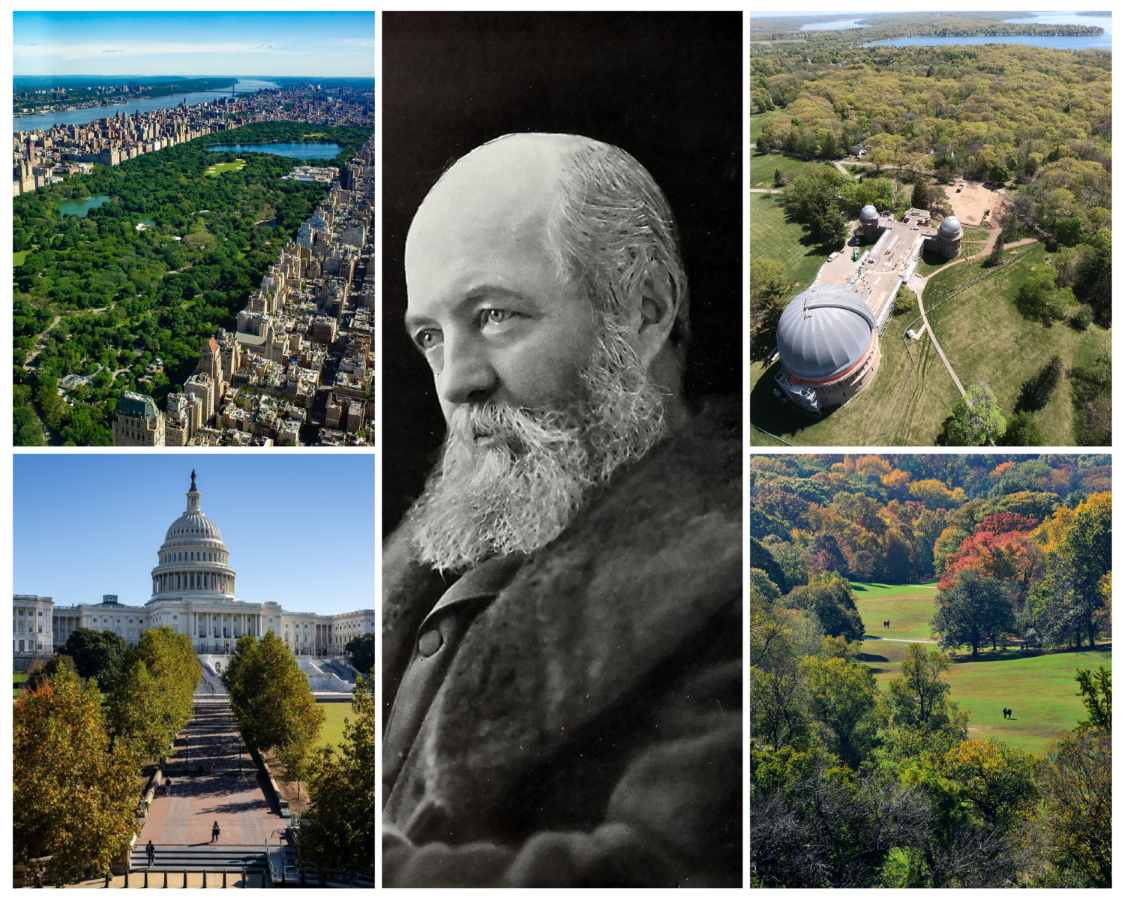

But when Burnham took the stage to be feted, he chose to deflect credit from himself and onto someone else, instead: “Each of you knows the name and genius of him who stands first in the heart and confidence of American artists, the creator of your own parks and many other city parks. He it is who has been our best adviser and our constant mentor. In the highest sense, he is the planner of the Exposition — Frederick Law Olmsted.”

Burnham paused to let that sink in. Then he added: “An artist, he paints with lakes and wooded slopes; with lawns and banks and forest-covered hills; with mountainsides and ocean views. He should stand where I do tonight, not for the deeds of later years alone, but for what his brain has wrought and his pen has taught for half a century.” A collective roar went up among those assembled.

See a collection of photographs of Olmsted's most famous parks

in the slideshow in this issue

Burnham’s tribute provides a sense of Olmsted’s stature and importance. But, effusive as it is, it fails to do him full justice. His life and career were just too sprawling and spectacular. Ask people today about Olmsted, and they’re likely to come back with a few stray details — best case. But his achievements are immense. Olmsted may well be the most important American historical figure that the average person knows least about.

He is best remembered as the pioneer of landscape architecture in the United States. He created a number of classic green spaces, often in collaboration with his sometime partner, Calvert Vaux. Olmsted’s 1858 debut, Central Park, was a masterpiece, a rigid rectangle of land transformed into an urban oasis. His next effort, Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, was another jewel.

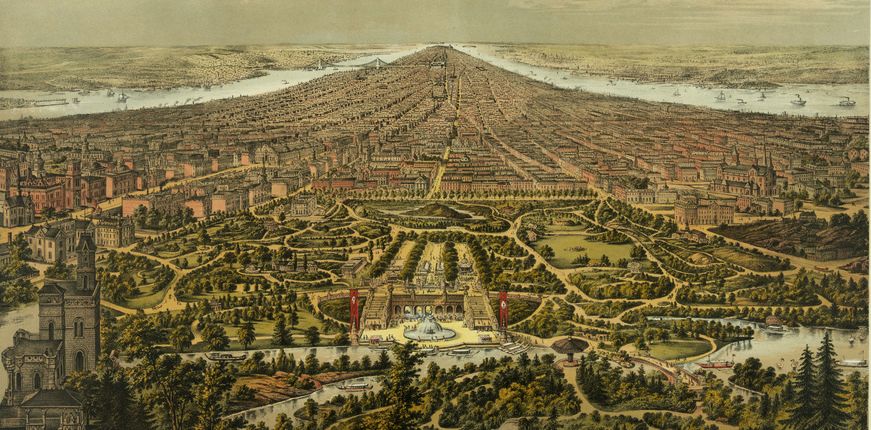

With his landscape creations, Olmsted demonstrated a talent for wildly innovative designs that made use of a city’s best natural features. In Chicago, for instance, he noted that Lake Michigan provided a dramatic backdrop. For the 1893 World Columbian Exposition there, he drew the lake directly into the fairgrounds, dredging a series of canals, Venice-style. In Montreal, his scheme called for exposing rocky crags and planting tree species associated with high altitudes, thereby giving a modest hill the appearance of an imposing alpine peak. Thus was born the city’s majestic Mount Royal Park.

an urban oasis in Brooklyn. Library of Congress." data-entity-type="file" data-entity-uuid="2c00abbd-82ce-4095-b879-fb4cdb44b673" src="https://www.americanheritage.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/Brooklyn%27s%20Prospect%20Park%2C%20LOC.jpg" width="1097" height="477" loading="lazy">

Often, Olmsted sensed that a city possessed a variety of landscapes suitable for parks. Why settle on a single tract? This insight spurred Olmsted and Vaux to invent the park system, a concept they debuted in 1868 with a set of three parks for Buffalo, New York. To insure that people could travel from one park to another, cloistered in greenspace all the way, their plan called for broad, tree-lined avenues. They even coined a term for these: “parkway.” (The term remains in use today, though it’s much abused, applied even to concrete medians planted with a few scraggly saplings.)

The park system proved a versatile concept, and Olmsted was prolific. He designed systems for the cities of Rochester, Milwaukee, and Louisville. He ringed Boston with a series of greenspaces — satisfyingly varied in terrain and design — that would come to be known as the Emerald Necklace.

But Olmsted wasn’t content to merely be a park-maker. So many other types of landscapes called out for his talents and touch. He designed the grounds of a number of private estates for wealthy patrons. He designed the campus of Stanford, Wellesley, and other colleges and universities. He also designed city neighborhoods, the U.S. Capitol grounds, the grounds of several mental institutions, and a pair of cemeteries. For his landscape architecture achievements alone, Olmsted would have earned a measure of lasting fame. At a time when open space is at a premium, he’s left us a legacy of green in city after city.

But Olmsted was also an environmentalist. He managed to roam most of the country (“I was born for a traveler,” he once said), and, along the way, he realized that some of the most striking natural landscapes were under siege. He played a crucial role in the early efforts to preserve Yosemite and Niagara Falls, for example. Over time, he began to bring environmental considerations to his park work, as well. He designed Boston’s Back Bay Fens not only as a park, but as America’s first effort at wetlands restoration.

Preserving wild places is different from crafting urban spaces, and it’s a vital Olmsted role that is often overlooked. He needs to be given his due as a pioneering environmentalist.

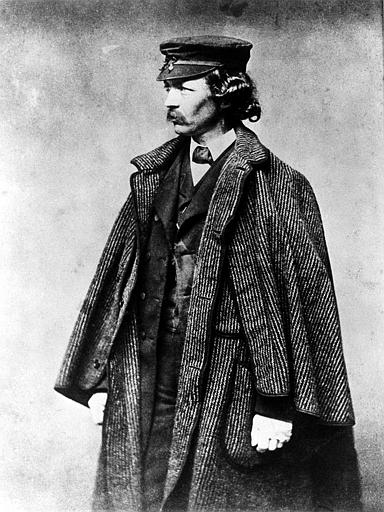

Olmsted was also a sailor and a scientific farmer, and a late bloomer nonpareil. During the Civil War, he helped manage the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a precursor to the Red Cross that managed hospitals and hospital ships. He also took a fascinating detour, moving out to California and managing a legendary but ill-starred