Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November/December 2022 | Volume 68, Issue 6

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November/December 2022 | Volume 68, Issue 6

Editor’s Note: Greg Melville teaches English at the U.S. Naval Academy and is the author of several books, including Over My Dead Body: Unearthing the Hidden History of America's Cemeteries, from which this essay was adapted.

Growing up in Bedford, Massachusetts, I almost never went inside Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in nearby Concord because it seemed so impossibly old and haunted. Even the name seemed unsettling.

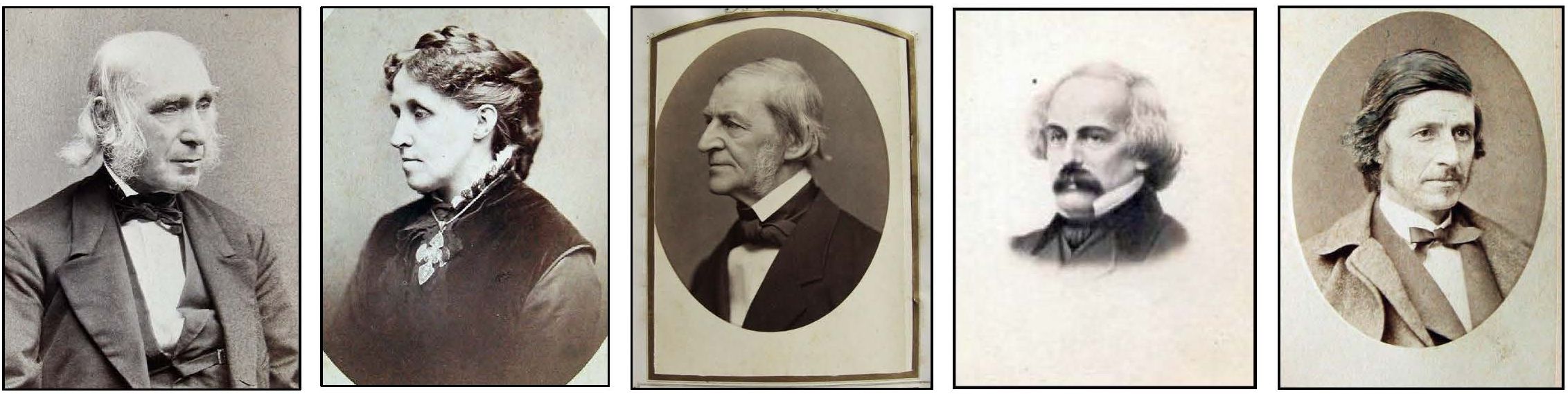

What I didn’t realize was that Sleepy Hollow is a national natural treasure. Before it became a graveyard, it was the outdoor playground for the literary titans Louisa May Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau, who all ended up buried there. Its environs directly influenced the transcendental movement in America.

Emerson, and to some extent, Thoreau, led the effort to create the cemetery to forever protect the property’s natural habitat from encroaching agriculture, deforestation, and development. In many ways, Sleepy Hollow served as the country’s first conservation land.

During the early and mid-19th century, the 17-acre wooded tract on the edge of downtown Concord that has the original footprint of the cemetery was surrounded by open farmlands. The property occupied a glacially formed ridge and a quiet hollow below it that looked, in Emerson’s words, like it “lies in nature’s hand.”

Hawthorne described it as “a shallow space scooped out among the woods.”

It was a popular leafy refuge and outdoor playground for locals. Emerson began spending time in the woods there in the early 1830s, when he moved into his grandfather’s nearby old home on the Concord River, called the Old Manse. While writing his famed essay “Nature,” he sought inspiration by losing himself among the property’s thick groves of white oaks and pitch pines.

The final product essentially became the founding document of transcendentalism, a literary and philosophical movement that laid the groundwork for the American environmental movement.

Transcendentalism emerged as a response to the Industrial Revolution, preaching that the most fundamental truths are found through individuality and intuition, not society and reason. It proposed that nature connects the human soul to God, joining them as one.

A cemetery in the woods was the natural extension of this philosophy — here, a body would dissolve