Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

October 2022 | Volume 67, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

October 2022 | Volume 67, Issue 5

Editor’s Note: Steve Wiegard is the author of ten books, mostly on American history, and he was the longtime senior writer at the San Francisco Chronicle and San Diego Evening Tribune. He adapted the following essay from his most recent book, 1876 – Year of the Gun: The Year Bat, Wyatt, Custer, Jesse and the Two Bills (Buffalo and Wild) created the Wild West, and Why It’s Still With Us.

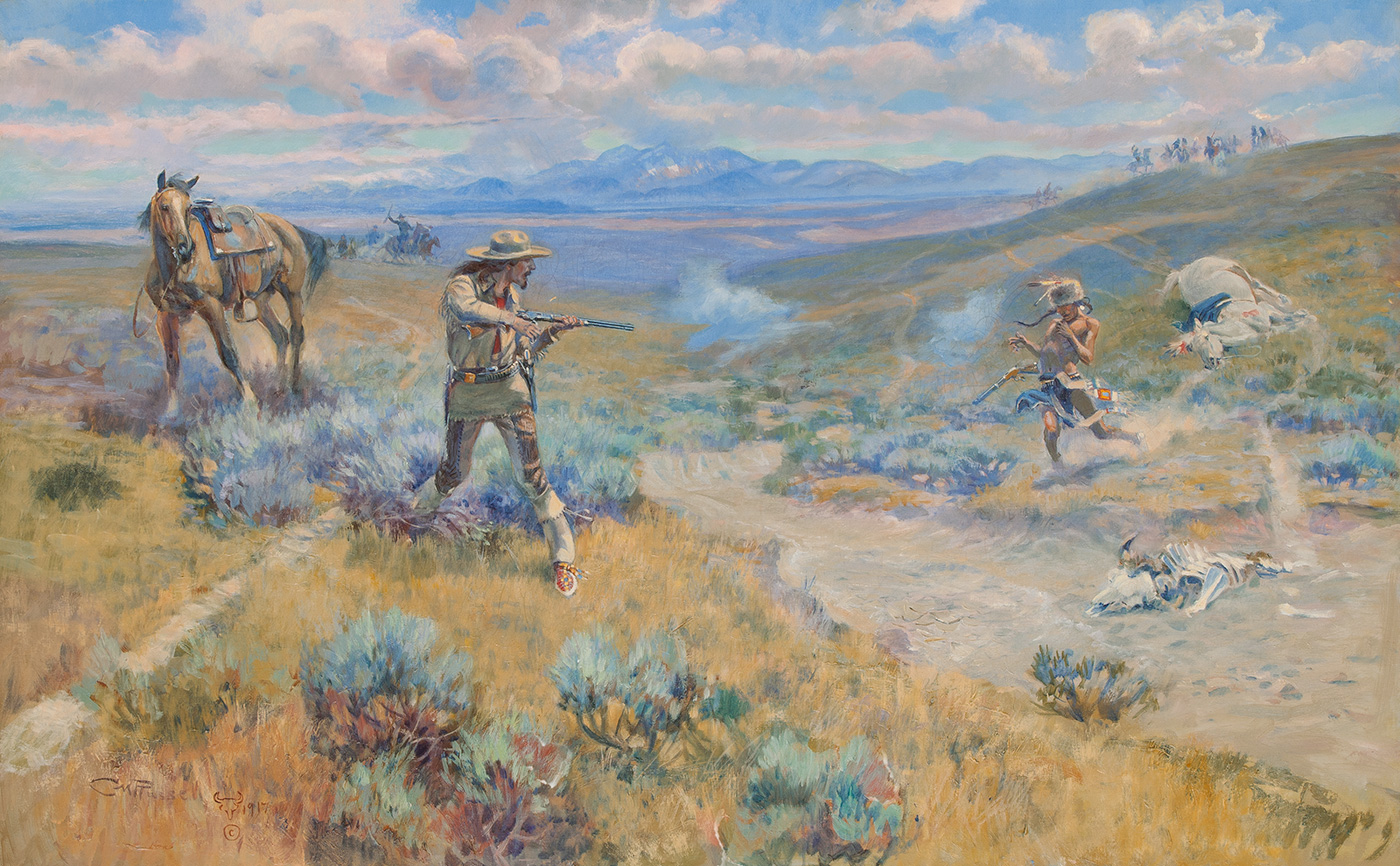

The plan was to ambush the ambushers. It was Will Cody’s idea. Colonel Wesley Merritt, newly in command of the U.S. Army’s vaunted 5th Cavalry, approved it. Captain Charles King and trooper Chris Madsen watched it unfold from their vantage points on grassy knolls above the dry creek bed.

The war against the Plains tribes of Sioux and Cheyenne in 1876 had not been going well for the U.S. Army. There had been two major battles since the beginning of the year, and so far, the Army was 0-2. On June 17, a force of about 1,000 men led by Gen. George Crook had met an Indian force of about the same size led by the Lakota Sioux warrior Crazy Horse, at Rosebud Creek in southern Montana. While Crook later claimed victory, the reality was that he retreated after the battle to a base camp in Wyoming and licked his wounds for the next seven weeks.

Eight days after the Battle of the Rosebud, about 40 percent of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry was killed after encountering a much larger force of Lakota and Cheyenne at the Little Bighorn River, about 50 miles northwest of the Rosebud fight. Unlike Crook, Custer did not live to claim a “victory.”

Now it was just after dawn on July 17, in the grasslands and low undulating hills of what is today northwestern Nebraska. For more than seven weeks, the 330 or so members of the 5th Cavalry had been striving to find some Indians to fight. Instead, in the words of one officer, the regiment “was principally occupied in fighting flies.”

Rations were short; dust was thick; the sun roasted skin, and the occasional thunderstorm soaked to the bone. News of the Crook and Custer defeats, when it finally reached the 5th, further lowered morale. One officer was so rattled he faked a lung hemorrhage by inducing a nose bleed, swallowing the blood and then coughing it up. Regimental surgeons were not impressed, but his resignation was approved anyway.

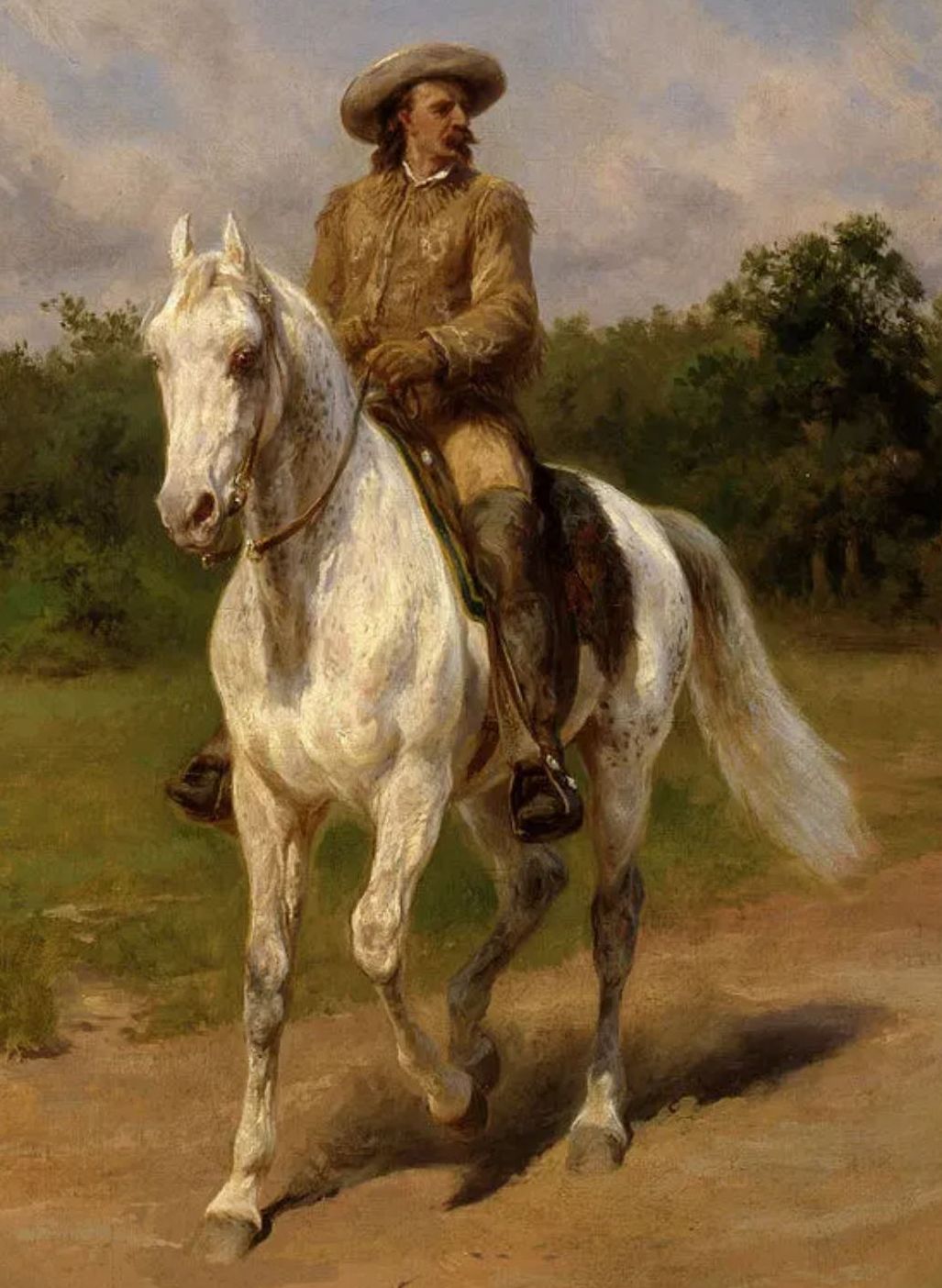

The 5th had been cheered somewhat on June 9 by the appearance of a tall, long-haired 30-year-old fellow who had hurriedly left his previous job as a touring stage actor to become the regiment’s chief of scouts. Will Cody had scouted for the regiment seven years before in a successful campaign against Lakota