Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2000 | Volume 51, Issue 1

Authors: Ken Chowder

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2000 | Volume 51, Issue 1

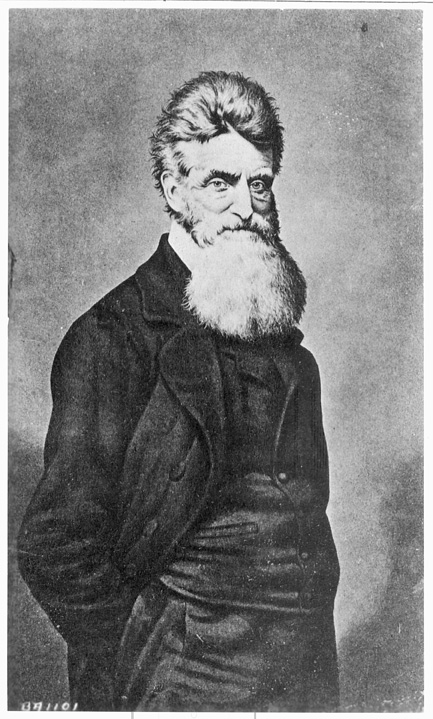

On December 2, 1859, a tall old man in a black coat, black pants, black vest, and black slouch hat climbed into a wagon and sat down on a black walnut box. His pants and coat were stained with blood; the box was his coffin; the old man was going to his execution. He had just handed a last note to his jailer: “I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood. I had...vainly flattered myself that, without very much bloodshed, it might be done.”

As he rode on his coffin, John Brown gazed out over the cornfields of Virginia. “This is a beautiful country,” he said. “I never had the pleasure of seeing it before.”

The United States in 1859 was a nation that harbored a ticking time bomb: the issue of slavery. And it was a place where an astonishing number of men were willing to die for their beliefs, certain they were following a higher law. John Brown was one of those God-fearing yet violent men. And he was already more than a man; he was a legend. In fact, there were two competing legends. To slaveholders he was utter evil—fanatic, murderer, liar, and lunatic, and horse thief to boot—while to abolitionists he had become the embodiment of all that was noble and courageous.

After a lifetime of failure, John Brown had at last found a kind of success. He was now a symbol that divided the nation, and his story was no longer about one man; it was a prophecy. The United States, like John Brown, was heading toward a gallows—the gallows of war.

A scaffold had been built in a field outside Charlestown, Virginia. There were rumors of a rescue attempt, and fifteen hundred soldiers, commanded by Col. Robert E. Lee, massed in the open field. No civilians were allowed within hearing range, but an actor from Virginia borrowed a uniform so he could watch John Brown die. “I looked at the traitor and terrorizer,” said John Wilkes Booth, “with unlimited, undeniable contempt.” Professor Thomas Jackson, who would in three years be known as Stonewall, was also watching: “The sheriff placed the rope around Brown’s neck, then threw a white cap over his head....When the rope was cut by a single blow, Brown fell through....There was very little motion of his person for several moments, and soon the wind blew his lifeless body to and fro.”

A Virginia colonel named J. T. L. Preston chanted: “So perish all such enemies of Virginia! All such enemies

But hanging was not the end of John Brown; it was the beginning. Northern churches’ bells tolled for him, and cannon boomed in salute. In Massachusetts, Henry David Thoreau spoke: “Some eighteen hundred years ago, Christ was crucified; This morning, perchance, Captain Brown was hung....He is not Old Brown any longer; he is an angel of light.”

John Brown’s soul was already marching on. But the flesh-and-blood John Brown—a tanner, shepherd, and farmer, a simple and innocent man who could kill in cold blood, a mixture of opposite parts who mirrored the paradoxical America of his time—this John Brown had already vanished, and he would rarely appear again. His life instead became the subject for 140 years of spin. John Brown has been used rather than considered by history; even today we are still spinning his story.

As far as history is concerned, John Brown was genuinely nobody until he was 56 years old—that is, until he began to kill people. Not that his life was without incident. He grew up in the wilderness of Ohio (he was born in 1800, when places like Detroit, Chicago, and Cleveland were still frontier stockades). He married at 20, lost his wife eleven years later, soon married again, and fathered a total of twenty children. Nine of them died before they reached adulthood.

At 17, Brown left his father’s tannery to start a competing one. “I acknowledge no master in human form,” he would say, many years later, when he was wounded and in chains at Harpers Ferry. The young man soon mastered the rural arts of farming, tanning, surveying, home building, and animal husbandry, but his most conspicuous talent seemed to be one for profuse and painful failure.

In the 1830s, with a growing network of canals making barren land worth thousands, Brown borrowed deeply to speculate in real estate—just in time for the disastrous Panic of 1837. The historian James Brewer Stewart, author of Holy Warriors, says that “Brown was a typical story of someone who invested, as thousands did, and lost thousands, as thousands did as well. Brown was swept along in a current of default and collapse.”

He tried breeding sheep, started another tannery, bought and sold cattle—each time a failure. When one venture lost money, Brown quietly appropriated funds from a partner in a new business and used it to pay the earlier loss. But in the end his farm tools, furniture, and sheep went on the auction block.

When his farm was sold, he seemed to snap. He refused to leave. With two sons and some old muskets, he barricaded himself in a cabin on the property. “I was makeing preparation for the commencement and vigorous prosecution of a tedious, distressing, wasteing, and long protracted war,” Brown wrote. The sheriff got up a posse and briefly put him in the Akron jail. No shots were fired, but it was an incident people would

Brown’s misadventures in business have drawn widely varying interpretations. His defenders say he had a large family to support; small wonder he wanted badly to make money. But others have seen his financial dreams as an obsession, a kind of fever that gave him delusions of wealth and made him act dishonestly.

Perhaps it was this long string of failures that created the revolutionary who burst upon the American scene in 1856. By that time Brown had long nurtured a vague and protean plan: He imagined a great event in which he—the small-time farmer who had failed in everything he touched—would be God’s messenger, a latter-day Moses who would lead his people from the accursed house of slavery. He had already, for years, been active in the Underground Railroad, hiding runaways and guiding them north toward Canada. In 1837, he stood up in the back of a church in Ohio and made his first public statement on human bondage, a single pungent sentence: “Here before God, in the presence of these witnesses, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery.” For years, however, this vow seemed to mean relatively little; in the early 1850s, as anger over slavery began to boil up all over the North, the frustrated and humiliated Brown was going from courtroom to courtroom embroiled in his own private miseries.

Finally, it happened. The John Brown we know was born in the place called Bloody Kansas. Slavery had long been barred from the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, but, in 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act decreed that the settlers of these territories would decide by vote whether to be free or slave. The act set up a competition between the two systems that would become indistinguishable from war.

Settlers from both sides flooded into Kansas. Five of John Brown’s sons made the long journey there from Ohio. But Brown himself did not go. He was in his mid-fifties, old by the actuarial tables of his day; he seemed broken.

Then, in March of 1855, five thousand pro-slavery Missourians—the hard-drinking, heavily armed “Border Ruffians”—rode into Kansas. “We came to vote, and we are going to vote or kill every God-damned abolitionist in the Territory,” their leader declared. The Ruffians seized the polling places, voted in their own legislature, and passed their own laws. Prison now awaited anyone who spoke against slavery.

In May, John Junior wrote to his father begging for his help. The free-soilers needed arms, “more than we need bread,” he said. “Now we want you to get for us these arms.” The very next day, Brown began raising money and gathering weapons and in August the old man left for Kansas, continuing to collect arms as he went.

In May 1856, a pro-slavery army sacked the free-soil town of Lawrence;

Late on the night of May 23, 1856, one of the group, probably Brown, banged on the door of James Doyle’s cabin. He ordered the men of the family outside at gunpoint, and Brown’s followers set upon three Doyles with broadswords. They split open heads and cut off arms. John Brown watched his men work. When it was over, he put a single bullet into the head of James Doyle.

His party went to two more cabins, dragged out and killed two more men. At the end, bodies lay in the bushes and floated in the creek; the murderers had made off with horses, saddles, and a bowie knife.

What came to be called the Pottawatomie Massacre ignited all-out war in Kansas. John Brown, the aged outsider, became an abolitionist leader. In August, some 250 Border Ruffians attacked the free-soil town of Osawatomie. Brown led 30 men in defending the town. He fought hard, but Osawatomie burned to the ground.

A few days later, when Brown rode into Lawrence on a gray horse, a crowd gathered to cheer “as if the president had come to town,” one man said. The spinning of John Brown had already begun. A Scottish reporter named James Redpath had found Brown’s men in their secret campsite, and “I left this sacred spot with a far higher respect for the Great Struggle than ever I had felt before.” And what of Pottawatomie? Brown had nothing to do with it, Redpath wrote. John Brown himself even prepared an admiring account of the Battle of Osawatomie for Eastern newspapers. Less than two weeks after the fight, a drama called Ossawattomie Brown was celebrating him on Broadway.

That autumn, peace finally came to Kansas, but not to John Brown. For the next three years, he traveled the East, occasionally returning to Kansas, beseeching abolitionists for guns and money, money and guns. His plan evolved into this: One night he and a small company of men would capture the federal armory and arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The invaders would take the guns there and leave. Local slaves would rise up to join them, making an army; together they all would drive south, and the revolution would snowball through the kingdom of slavery.

On the rainy night of October 16, 1859, Brown led a determined little procession down the road to Harpers Ferry. Some 20 men were making a direct attack on the U.S. government; they would liberate four million souls from bondage. At first, the raid went like clockwork. The armory was protected by just one man, and he quickly surrendered. The invaders cut telegraph lines and rounded up hostages on the

Then, Brown’s difficulties began. A local doctor rode out screaming, “Insurrection!,” and by midmorning men in the heights behind town were taking potshots down at Brown’s followers. Meanwhile, John Brown quietly ordered breakfast from a hotel for his hostages. As Dennis Frye, the former chief historian at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, asks, “The question is, why didn’t John Brown attempt to leave? Why did he stay in Harpers Ferry?” Russell Banks, the author of the recent John Brown novel Cloudsplitter, has an answer: “He stayed and he stayed, and it seems to me a deliberate, resigned act of martyrdom.”

At noon, a company of Virginia militia entered town, took the bridge, and closed the only true escape route. By the end of the day, John Brown’s revolution was failing. Eight invaders were dead or dying. Five others were cut off from the main group. Two had escaped across the river; two had been captured. Only five raiders were still fit to fight. Brown gathered his men in a small brick building, the enginehouse, for the long, cold night.

The first light of October 18 showed Brown and his tiny band an armory yard lined with U.S. Marines, under the command of Col. Robert E. Lee. A young lieutenant, J. E. B. Stuart, approached beneath a white flag and handed over a note asking the raiders to surrender. Brown refused. At that Stuart jumped aside, waved his cap, and the Marines stormed forward with a heavy ladder. The door gave way. Lt. Israel Green tried to run Brown through, but his blade struck the old man’s belt buckle; God, for the moment, had saved John Brown.

A few hours later, as he lay in a small room at the armory, bound and bleeding, Brown’s real revolution began. Gov. Henry A. Wise of Virginia arrived with a retinue of reporters. Did Brown want the reporters removed? asked Robert E. Lee. Definitely not. “Brown said he was by no means annoyed,” one reporter wrote. For the old man was now beginning a campaign that would win half of America. He told the reporters: “I wish to say...that you had better—all you people of the South—prepare yourselves for a settlement of this question....You may dispose of me very easily—I am nearly disposed of now; but this question is still to be settled—this negro question I mean; the end of that is not yet.”

His crusade for acceptance would not be easy. At first, he was no hero. Leaders of the Republican party organized anti-Brown protests; “John Brown was no Republican,” Abraham Lincoln said. Even the Liberator, published by the staunch abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, called the raid “misguided, wild, and apparently insane.”

In the South, the initial reaction was derision—the Richmond Dispatch called the foray “miserably weak and contemptible”—but that

A reign of terror began in the South. A minister who spoke out against the treatment of slaves was publicly whipped; a man who spoke sympathetically about the raid found himself thrown in jail. Four state legislatures appropriated military funds. Georgia set aside seventy-five thousand dollars; Alabama, almost three times as much.

Brown’s trial took just one week. As Virginia hurried toward a verdict, the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher preached, “Let no man pray that Brown be spared! Let Virginia make him a martyr!” John Brown read Beecher’s words in his cell. He wrote “Good” beside them.

On November 2, the jury, after deliberating for forty-five minutes, reached its verdict. Guilty. Before he was sentenced, Brown rose to address the court: “I see a book kissed here, … the Bible.... that teaches me to ‘remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them.’ I endeavored to act up to that instruction....I believe that to have interfered…in behalf of His despised poor was not wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life..., and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded...I say let it be done!”

For the next month, the Charlestown jail cell was John Brown’s pulpit. All over the North, Brown knew, people were reading his words. He wrote, “You know that Christ once armed Peter. So also in my case, I think he put a sword into my hand, and there continued it so long as he saw best, and then kindly took it from me.”

The author of the Pottawatomie Massacre was now comparing himself to Jesus Christ. And he was not alone. Even the temperate Ralph Waldo Emerson called him “the new Saint whose fate yet hangs in suspense but whose martyrdom if it shall be perfected, will make the gallows as glorious as the cross.” There were rescue plans, but John Brown did not want to escape. “I am worth inconceivably more to hang than for any other purpose,” he wrote.

He got that wish on December 2, and the mythologizing of the man began in earnest. Thoreau, Emerson, Victor Hugo, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman all wrote essays or poems immortalizing him. James Redpath eagerly waited for the moment when “Old B was in heaven”; just a month after the execution, he published the first biography. Forty thousand copies of the book sold in a single month.

Less than a year and a half later, the guns began firing on Fort Sumter. If the country had been a tinder box, it seemed to many that John Brown had been the spark. “Did John Brown fail?” Frederick Douglass wrote. “...John Brown began the war

His reputation seemed secure, impermeable. The first biographies of the man James Redpath called the “warrior saint” all glorified him. But then, in 1910, Oswald Garrison Villard, grandson of the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, wrote a massive and carefully researched book that pictured Brown as a muddled, pugnacious, bumbling, and homicidal madman. Nineteen years later, Robert Penn Warren issued a similar (and derivative) study. Perhaps the most influential image of John Brown came, not surprisingly, from Hollywood: In Santa Fe Trail Raymond Massey portrayed him as a lunatic, pure and simple.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that John Brown the hero re-emerged. Two excellent studies by Stephen B. Oates and Richard Owen Boyer captured the core of the conundrum: Brown was stubborn, monomaniacal, egotistical, self-righteous, and sometimes deceitful; yet he was, at certain times, a great man. Boyer, in particular, clearly admired him: At bottom, Brown “was an American who gave his life that millions of other Americans might be free.”

Among African-Americans, Brown’s heroism has never been in doubt. Frederick Douglass praised him in print; W. E. B. Du Bois published a 400-page celebration of him in 1909; Malcolm X said he wouldn’t mind being with white people if they were like John Brown; and Alice Walker, in a poem, even wondered if, in an earlier incarnation, she herself hadn’t once been John Brown.

But, as Russell Banks points out, Brown’s “acts mean completely different things to Americans, depending upon their skin color.” And the image that most white people today have of John Brown is still of the wild-eyed, bloodthirsty madman. After all, he believed that God spoke to him; he killed people at Pottawatomie in cold blood; he launched an attack on the U.S. government at Harpers Ferry with not even two dozen men. How sane could he have been?

Let’s look at those charges one by one. First: He conversed with God. Brown’s religious principles, everyone agrees, were absolutely central to the man. As a child, he learned virtually the entire Bible by heart. At 16, he traveled to New England to study for the ministry. He gave up after a few months, but remained deeply serious about his Calvinist beliefs. Brown had a great yearning for justice for all men, yet a rage for bloody revenge. These qualities may seem paradoxical to us, but they were ones that John Brown had in common with his deity. The angry God of the Old Testament punished evil: An eye cost exactly an eye.

If God spoke directly to John Brown, the deity also spoke to William Lloyd Garrison and to the slave revolutionary Nat Turner. To converse with God, in Brown’s day, did not mean that you were eccentric. In fact, God was on everyone’s side. John Brown saw the story

Second: He killed in cold blood. Brown was a violent man, but he lived in increasingly violent times. Slavery itself was of course a violent practice. In 1831, Nat Turner led 70 slaves to revolt; they killed 57 white men, women, and children. A few years later, a clergyman named Elijah Lovejoy was gunned down for speaking out against slavery. By the 1850s, another distinguished clergyman, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, could lead a mob to the federal courthouse in Boston and attack the place with axes and guns. “I can only make my life worth living,” Higginson vowed, “by becoming a revolutionist.” During the struggle in Kansas, Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Church in Brooklyn was blithely shipping Sharps rifles west; “there are times,” the famous preacher said, “when self-defense is a religious duty.” By the late 50s, writes the historian James Stewart, even Congress was “a place where fist fights became common … a place where people came armed … a place where people flashed Bowie knives.” On February 5, 1858, a brawl broke out between North and South in the House of Representatives; congressmen rolled on the floor, scratching and gouging each other.

Brown’s Pottawatomie Massacre was directly connected to this national chaos. On the very day that Brown heard about the sacking of Lawrence, another disturbing report reached him from Washington: A Southern congressman had attacked Senator Charles Sumner, a fierce abolitionist, on the floor of Congress, caning him almost to death for insulting the South. When the news got to Brown’s campsite, according to his son Salmon, “the men went crazy— crazy. It seemed to be the finishing, decisive touch.” Brown ordered his men to sharpen their broadswords and set off toward Pottawatomie, the creek whose name still stains his reputation.

So it is that “Brown is simply part of a very violent world,” according to the historian Paul Finkelman. At Pottawatomie, Finkelman says, “Brown was going after particular men who were dangerous to the very survival of the free-state settlers in the area.” But Dennis Frye has a less analytical (and less sympathetic) reaction: “Pottawatomie was cold-blooded murder. It was killing people up close based on anger and vengeance.”

To Bruce Olds, the author of

Maybe Pottawatomie was insane, and maybe it was not. But what about that Harpers Ferry plan—a tiny band attacking the U.S. government, hoping to concoct a revolution that would carry across the South? Clearly that was crazy.

Yes and no. If it was crazy, it was not unique. Dozens of people, often bearing arms, had gone South to rescue slaves. Secret military societies flourished on both sides, plotting to expand or destroy the system of slavery by force. Far from being the product of a singular cracked mind, the plan was similar to a number of others, including one by a Boston attorney named Lysander Spooner. James Horton, a leading African-American history scholar, offers an interesting scenario. “Was Brown crazy to assume he could encourage slave rebellion?...Think about the possibility of Nat Turner well-armed, well-equipped....Nat Turner might have done some pretty amazing things,” Horton says. “It was perfectly rational and reasonable for John Brown to believe he could encourage slaves to rebel.”

But the question of Brown’s sanity still provokes dissension among experts. Was he crazy? “He was obsessed,” Bruce Olds says, “he was fanatical, he was monomaniacal, he was a zealot, and...psychologically unbalanced.” Paul Finkelman disagrees: Brown “is a bad tactician, he’s a bad strategist, he’s a bad planner, he’s not a very good general—but he’s not crazy.”

Some believe that there is a very particular reason why Brown’s reputation as a madman has clung to him. Russell Banks and James Horton make the same argument. “The reason white people think he was mad,” Banks says, “is that he was a white man and he was willing to sacrifice his life in order to liberate black Americans.” “We should be very careful,” Horton says, “about assuming that a white man who is willing to put his life on the line for black people is, of necessity, crazy.”

Perhaps it is reasonable to say this: A society where slavery exists is, by nature, one where human values are skewed. America before the Civil War was a violent society, twisted by slavery. Even sober and eminent people became firebrands. John Brown had many peculiarities of his own, but he was not outside his society; to a great degree, he represented it, in its many excesses.

The past, as always, continues to change, and the spinning of John Brown’s story goes on today. The same events—the raid on Harpers Ferry or the Pottawatomie Massacre—are still seen in totally different ways. What is perhaps most remarkable is that elements at both the left and right ends of American society are at this moment vitally interested in the story of John Brown.

On the left is a group of historical writers and teachers called Allies

Go a good deal farther to the left, and there has long been admiration for John Brown. In 1975, the Weather Underground put out a journal called Osawatomie. In the late 1970s, a group calling itself the John Brown Brigade engaged in pitched battles with the Ku Klux Klan; in one confrontation in Greensboro, North Carolina in 1979, five members of the John Brown Brigade were shot and killed. Writers also continue to draw parallels between John Brown and virtually any leftist who uses political violence, including the Symbionese Liberation Army (the kidnappers of Patty Hearst in the 1970s), the Islamic terrorists who allegedly set off a bomb in the World Trade Center in Manhattan, and Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber.

At the same time, John Brown is frequently compared to those at the far opposite end of the political spectrum. Right-to-life extremists have bombed abortion clinics and murdered doctors; they have, in short, killed for a cause they believed in, just as John Brown did. Paul Hill was convicted of murdering a doctor who performed abortions; it was, Hill said, the Lord’s bidding: “There’s no question in my mind that it was what the Lord wanted me to do, to shoot John Britton to prevent him from killing unborn children.” If that sounds quite like John Brown, it was no accident. From death row, Hill wrote to the historian Dan Stowell that Brown’s “example has and continues to serve as a source of encouragement to me....Both of us looked to the scriptures for direction, and the providential similarities between the oppressive circumstances we faced and our general understandings of the appropriate means to deliver the oppressed have resulted in my being encouraged to pursue a path which is in many ways similar to his.” Shortly before his execution Hill wrote that “the political impact of Brown’s actions continues to serve as a powerful paradigm in my understanding of the potential effects the use of defensive force may have for the unborn.”

Nor was the murder that Hill committed the only right-wing violence that has been compared to Brown’s. The Oklahoma

He gets compared to anarchists, leftist revolutionaries, and right-wing extremists. The spinning of John Brown, in short, is still going strong. But what does that make him? This much, at least, is certain: John Brown is a vital presence for all sorts of people today. In February PBS’s The American Experience is broadcasting a 90-minute documentary about him. Russell Banks’s novel Cloudsplitter was a critical success and a bestseller, as well. On the verge of his 200th birthday (this May 9), John Brown is oddly present. Perhaps there is one compelling reason for his revival in this new millennium: Perhaps the violent, excessive, morally torn society that John Brown represents so aptly was not just his own antebellum America, but this land, now.