Authors:

Historic Era: Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2022, Summer 2025 | Volume 67, Issue 4

Authors: David McCullough

Historic Era: Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2022, Summer 2025 | Volume 67, Issue 4

Editor's Note: In memory of David McCullough, we reprint here the first article he wrote after he joined the staff of American Heritage. Expanding this essay on his own time over the next two years, McCullough published his first book, The Johnstown Flood, in 1968.

The southwestern corner of Cambria County, Pennsylvania, is high, burly mountain country with fast trout streams and miles of dark forest. The air smells clean and wonderful, even in the drab little coal towns tucked back in the hills, and the views are awesome, with far-off patches of green farmland under a sky filled with towering white clouds. Then, at Johnstown, it is as though the bottom dropped out of the old earth and left it angry and smouldering.

The city sits down in a great hole in the Alleghenies, along a gorge that is anywhere from 500 to 1000 feet deep and has sides as steep as a sluice. It is shrouded in smoke most of the time, and you can hear it whistling and clanking from miles off. For, like Pittsburgh, which is 75 miles to the west, Johnstown is a steel center. Blast furnaces light up the sky at night; carloads of coal rumble along the main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad within a few blocks of the tree-shaded town square; and the rivers, the Stony Creek and the Little Conemaugh, are the color of a new baseball glove.

The rivers meet at Johnstown. The Stony Creek flows in from the south; the Little Conemaugh drops down the mountains from the east. At Johnstown, they form the Conemaugh, which later joins the Kiskiminitas to the west, which in turn flows into the Allegheny above Pittsburgh. The rivers are really no more than big mountain streams.

Below “the Point,” where the rivers meet, a massive seven-arched stone bridge carries the Pennsylvania tracks across the Conemaugh. The bridge was built in 1887. It is one of the oldest structures in Johnstown and the city’s most haunting reminder of the horror that took place there seventy-seven years ago and gave to Johnstown, for better or worse, its fame as the Flood City.

The official memorial to the flood is up on the high ground, in Grandview Cemetery, where 777 white marble headstones are set out beneath a sculptured granite “Monument to the Unknown Dead.” These unknown dead are not quite a third of the people who died in the valley below, for in Johnstown, on Friday, May 31, 1889, within a few hours, more than 2200 people were killed. The number of “missing” totaled 967.

The Johnstown destroyed by the flood was a bustling, two-fisted company town that seemed well on its way to farmland fortune. The company was the Cambria Iron Company, a fifty-million-dollar iron and steel empire that employed six thousand men, owned and operated its own trains, tracks, coal mines, and coke ovens, a company store, a woolen mill, a brick works, and some 700 houses for its mill hands. Its principal products were steel rails and barbed wire, the latter turned out in the Gautier Works, a subsidiary. Before the Civil War, Cambria was the biggest iron works in the country. In 1861, the first Bessemer-type converter was set up there by William Kelly, the “Irish crank” from Louisville. With the war came boom times. After the war, the age of cheap steel was underway. By 1870, what had started out in 1800 as a backwoods trading center was a city with seven hotels, a library and night school, six breweries, and sixty-two saloons. By the time of the flood, there were 30,000 people living in the valley, in Johnstown and in a cluster of neighboring boroughs known as Kernville, Prospect, East Conemaugh, Franklin, Woodvale, Conemaugh, Cambria City, Millvale, Morrellville, Moxham, and Grubtown. Johnstown was the center of the lot, geographically and in every other way. There was an opera house on Washington Street, another on Main, and a park with a fountain; some of the commercial buildings were as high as four and five stories. But then as now, it was a steel town, and so not a pretty place. The workmen lived in cheap pine houses along the river flats, where, as a newspaper of the day put it, “loud and pestiferous stinks prevail.” Hundreds of them would die dreadful deaths in the flood; but hundreds more would fare better than many of their fellow residents who lived in big brick houses on higher ground or along such streets as Maple Avenue, in the Woodvale section. Maple Avenue looked like a green tunnel that May in 1889. The trees with their new leaves reached over the quiet street and sent long, soft shadows across neat lawns and white frame houses. When the flood had passed, there would be no trace of Maple Avenue. The flood happened, as everyone knows, because “the dam busted” and sent a wall of water rushing upon the city and all the poor mortals who had failed to “run for the hills.” The dam was Lake Conemaugh’s South Fork dam. Fourteen miles east of Johnstown, up South Fork Run, which feeds into the Little Conemaugh at the town of South Fork, it was said to be the biggest earthen dam

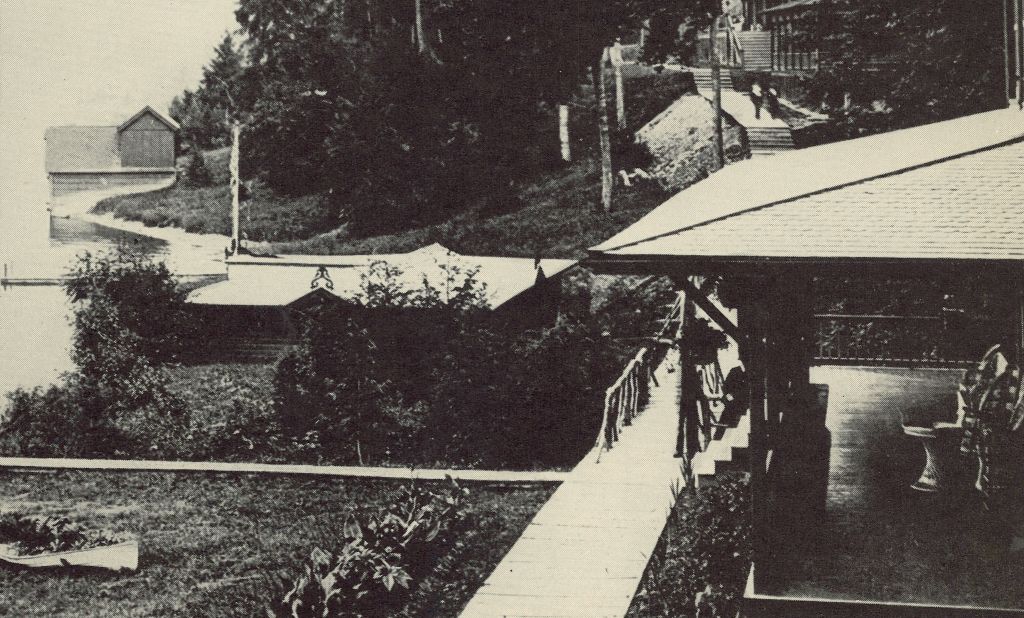

The lake and dam were owned by the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, a private summer resort started by a group of wealthy “sportsmen” from Pittsburgh. There was a cavernous, three-story clubhouse halfway down the western side of the lake, with a deep front porch that ran the length of it and offered a good view of the water. There were flower beds and boardwalks that led to sixteen “Queen Anne cottages” close by along the shore front. There were rowboats and sailboats tied up at boathouses, a fleet of fifty canoes, and two small yachts. In 1889, there were sixty-six names on the membership list. Among them were such distinguished Pittsburgh families as Phipps, Chalfant, Laughlin, McClintock. Also among them were Andrew Mellon, Henry Frick, and Andrew Carnegie. The group had been organized in Pittsburgh in 1879 after one of their number, a Benjamin F. Ruff, had bought the dam and lake from a congressman named John Reilly, who had bought it four years before from the Pennsylvania Railroad. When the club took possession of the property, the dam was in bad shape. It had been built in the late 1840’s to provide water during dry spells for the Johnstown canal basin, which was part of a system of railroads and canals linking Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. Around 1850, the water route was converted to transit by steam railroad. Then the Pennsylvania Railroad bought up the whole system in 1857, and the lake was part of the package. What the railroad got was a lake it did not need, held back by a dam that had been deteriorating almost from the day it had been finished. Understandably, not much was done to improve it. In 1862, during a July downpour, a stone culvert at the base of the dam gave way and a sizable chunk of the wall washed out. But damage was slight, since the water level had been low. After that, the dam moldered away for seventeen years until the Pittsburgh men bought it. By then, the discharge pipes at the base had been removed and sold for scrap, and leaks were numerous. The leaks were patched, and the old break was fixed by dumping in stumps, straw, clay, brush, virtually anything at hand. It was a slipshod job, to say the least. When the work was finished, the dam was only slightly higher, but there was a sag in the center, where it should have been highest. The idea of giving the structure a major overhaul does not seem to have been considered. The lake filled in, and it was not long until summer guests, under parasols and blue skies, were arriving in carriages from the depot down in South Fork and crossing over to the clubhouse side of the lake by way of the dirt road along the crest of the dam. On their right, the steep face of the dam dropped away to the valley below. On their left was the smooth lake bordered by woods and meadows. It was a spectacular setting. It was no Newport or Saratoga, not by a long, long shot. It was, in fact, a rather simple and very peaceful mountain summer place, nothing very fancy or ostentatious. For some of the young sons and daughters of the well-to-do Pittsburghers, it may even have been something of a bore. The club and the dam were looked upon by locals with mixed feelings. There was certainly a measure of pride to be taken from the idea that the Pittsburghers with all their money thought enough of the country around South Fork to want to summer there. There was also a measure of sporting fun to be taken out of the well-stocked lake. Off season, it was an easy matter for a Conemaugh Valley man or boy to slip onto the property and bring home supper. When the club tried to clamp down, it succeeded mainly in adding to the sport. Night fishing was taken up. Relations between the members and natives became strained. That there was serious concern in Johnstown about the dam is quite clear. How widespread it actually was is another matter. After the disaster, there were any number of local citizens who came forth to say they had long had a deep fear of the dam and prophetic concern for all who lived beneath its shadow. Certainly, they had ample cause for concern. Johnstown and the whole Conemaugh Valley seldom got through a spring without floods. In 1885, ’87, and ’88 there had been bad floods. Heavy snows in the mountains would cut loose during a sudden thaw, or a spring thunderstorm would slash down

One man who unmistakably set out to do something about the danger of the South Fork dam, before May 31, 1889, was Daniel J. Morrell, president of Cambria Iron and the biggest man in Johnstown. A Philadelphian and a Quaker, Morrell had taken charge of Cambria Iron before the Civil War, when the company was in serious financial trouble. In short order, he became one of the greatest iron masters of his day, a strong voice in the Republican party, a man who looked upon Andrew Carnegie as an upstart in the business. When the Pittsburgh men bought the old dam in 1879 and announced what they planned to do with it, the Cambria Iron Company, as one of its executives later said, was “considerably exercised.” The following year, after the new owners had completed their repairs, Morrell sent his chief engineer, John Fulton, to look the job over. The report from Fulton was that the dam had been inadequately repaired, leaving a large leak that was causing trouble; also, that discharge pipes were needed, so that the water level could be lowered if necessary; and that a thorough overhaul was called for. The report had no visible effect on the club management. Benjamin Ruff replied by saying that the repairs already made were adequate, and ended by flatly stating to Morrell, “You and your people are in no danger from our enterprise.” Morrell refused to let it go at that. He wrote Ruff that the dam was a “perpetual menace to the lives and property of those residing in the upper valley of the Conemaugh.” He urged that some way be provided for lowering the water “in case of trouble” and offered to have Cambria Iron help foot the bill. The club declined the offer. The matter was dropped. In 1885, four years before the dam broke, Daniel Morrell died at the age of sixty-four. Two years after that, Benjamin Ruff died. When the rains began on the afternoon of Thursday, May 30, 1889, there was only one club member at the lake. He

The rain was cold and came down steadily through the afternoon and on into the evening. By eleven that night, it was a deluge, with great crashes of thunder that echoed through the mountains. No one could remember a worse storm. In the morning, a pail left outside would have eight inches of water in it. At dawn, young John Parke would go down to the lake to find that overnight, the water at the dam had risen two feet. He would then move quickly to the opposite end of the lake, where South Fork Creek, its main feeder and ordinarily about two feet deep, was stripping limbs off trees five feet above the ground. In Johnstown on Thursday afternoon, the crowds were back from the cemetery by the time the rain started. It had been the customary sort of Decoration Day. The Reverend H. L. Chapman, who lived near the park, said the city was “in its gayest mood, with flags, banners, and flowers everywhere.” There were parades and speeches and plenty of visitors in from the neighboring towns of Somerset, Altoona, and New Florence. By nightfall there was a good deal of flood talk about. There had been 11 days of rain already that month, after a fourteen-inch snowstorm in April that had melted almost as suddenly as it had come down. The rivers were already running high. The rain hammered down all night. Friday morning, a heavy mist hung over the city. The sky was dark. That the valley was in for a bad time was very clear. A landslide had caved in the stable at Kress’s Brewery before sunup. By 7:00, the rivers were rising fast. Cambria Iron sent its men home at seven to look after their families. At ten o’clock, the superintendent at the Gautier wire works ordered a shutdown after some of the men reminded him that the ground where he stood had once been under four feet of water before the mill was built. Main Street was already under water; a teamster had driven his wagon into a cellar excavation and drowned. At noon, the Poplar Street and Cambria City bridges went. Rowboats were moving past front doors to rescue stranded families. This was becoming a springtime routine for Johnstowners, one of the rites of the season. The Stony Creek and Little Conemaugh were rising at better than a foot an hour. At precisely 1:30, Henry Wilson Storey, the historian for Cambria County and quite a tall man, telephoned

By now, hundreds of families had seen enough. The water had never been this high, even in the worst floods. They began moving out, struggling through the water to the high ground. Some went a little sheepishly, dreading the looks they might get when the storm had passed and they came back down again. But most of Johnstown stayed put. And quite a few citizens had a fine time of it. A good example was attorney Horace Rose, a respected civic leader and family man who should have had a lot more sense. He went over to Main Street after breakfast to look at how things were going, and stopped to pass the time with his friend Charles Zimmerman. “Charley,” he said, “you and I have scored fifty years and this is the first time we ever saw a cow drink Stony Creek river water on Main Street.” He then returned home and found it necessary to build a log raft in order to float himself over to his back porch. Once inside, like nearly every other father in town, he busied himself taking up the carpets and furniture. He also “marked with sadness” that the water “with its muddy freight” had ruined his new wallpaper. Then he and his wife and four sons moved upstairs, where the morning took on the air of a family picnic. They boiled coffee over the grate, called to neighbors from the window, and joked about their troubles. After a while, he went up to the attic, propped himself in a window, and passed the time shooting at rats that were struggling along the wall of a stable nearby. That there might be trouble at the South Fork dam never once entered his mind. Before noon, two sections of the day express from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia pulled into the big marshaling yards at East Conemaugh, three miles up the Little Conemaugh from Johnstown. Inside, some fifty passengers sat and waited. They were told there had been a landslide up the line, at a place called Lilly. The rain beaded on the glass of the windows, but beyond, they could make out the brown surge of the river. At one o’clock, Mrs. Hettie Ogle, manager of the Johnstown telegraph office, moved her staff to the second floor. At three, she sent a message to the manager of the Pittsburgh office: SOUTH FORK OPERATOR SAYS THE DAM IS ABOUT TO GO. At 3:15, she put in a call to the Tribune to report that the Pennsylvania’s freight agent had called to say that the situation at the dam was getting worse by the minute. Mrs. Ogle’s telegram to Pittsburgh was to be her last. By 3:15, the water of Lake Conemaugh was already on its way. Hours earlier, in the driving rain, Colonel Unger, John Parke, and their work crew had tried frantically to free the dam’s one spillway of the big iron grate that had been

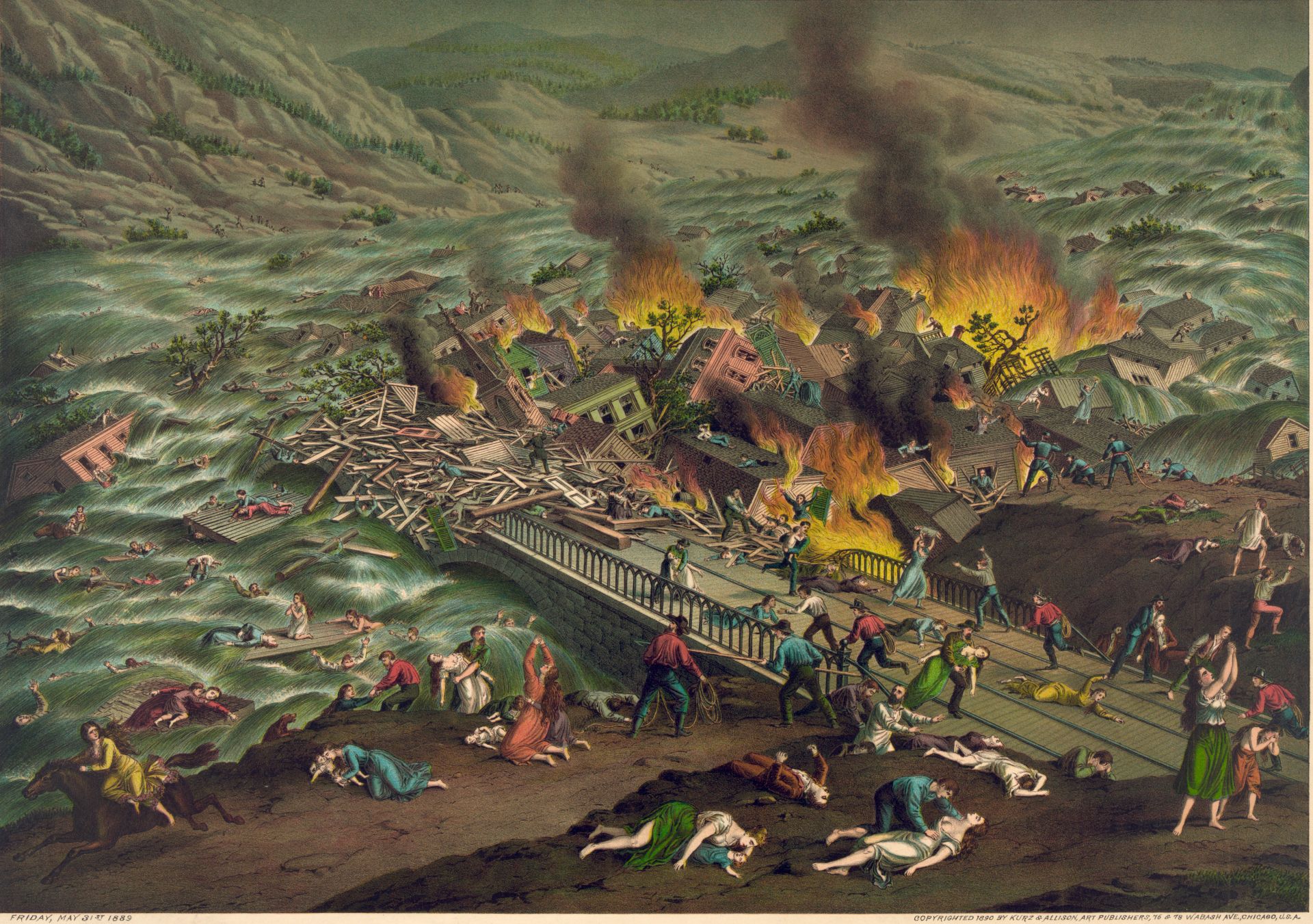

The grate was clogged with debris and would not budge. It was now only a matter of time. Already, there were big leaks spurting water from the face of the dam. A frantic and futile attempt was made to cut a second spillway at the other end of the dam. The men could get nowhere in the rocky soil. It was two miles down the valley to South Fork, and John Parke made it on horseback in about ten minutes. The wolf cry had begun again. Parke was young and not known in the area, which may have been part of the reason for the failure of his mission. But the telegraph operator thought enough of him and his warning to pass the word on down the line. By the time Parke arrived back at the dam, the end was very near. Water was coming over the top in a big glassy sheet several feet deep. Shortly after three o’clock, the water sliced a huge notch out of the center. Then, with an awful roar, the dam just moved away. A small boy with the big name of U. Ed Schwartzentruver saw it happen from a nearby hillside. He had been there all morning with his friends, standing in the rain watching the excitement. Seventy-six years later, on his front porch on Grant Street in South Fork, not quite ninety years old and nearly blind, he would talk about it as though it had happened the day before. “There was a man named Buchanan up there, John Buchanan. He kept telling Colonel Unger to pull out that big iron screen in the spillway. But Colonel Unger wouldn’t do it. And then when he would, it was too late. Then the whole dam seemed to push out all at once. Not a break. Just one big push.” The water crashed down the valley tree-top high. A farm was destroyed in an instant. Giant chunks of the dam, boulders, logs, and whole trees were swept ahead of the wall of water and began to build into what would be one of the flood’s most brutal killers, a grinding, crushing mass of debris. At South Fork, the damage was relatively slight. Some twenty houses were destroyed, and only two people drowned. The little town sits on high ground; it was out of the direct path of the onslaught. Farther on, the water smashed into its first major obstacle, a seventy-foot-high

Because of the great friction created by the debris and by the rough terrain of the valley itself, the bottom of the mass of water moved much slower than the top, causing the top to continually slide over the front of the advancing wall. This created a violent downward smashing of water that would crush almost anything in its path. After the disaster, engineers calculated that a man caught under it would have had about as much chance as if he had been standing directly under Niagara Falls. Past Mineral Point, a work train driven by engineer John Hess sat on the Pennsylvania tracks pointed downstream. Hess heard the water coming, realized what was happening, and, like some mythical folk hero, he put on full steam, tied down his whistle, and went shrieking toward East Conemaugh and the railroad yards where the two sections of the day express sat waiting. For three hours, passengers on board had been looking out the windows or gathering in clusters along the aisles to talk about the storm and the dam up the river that they had been hearing about. Twice, their trains had been moved back from the river as the water moved closer. Twice, they had seen the tracks they had been standing on wash out. At the sound of Hess’s whistle, a conductor and brakeman entered each coach and asked the passengers to move out of the train and up onto the hillside, and to please move as quickly as possible. About half of them made it. Seconds later, Hess and his engine came barreling into the yards. He leaped to the ground and ran to his home in time to get his family to higher ground. The whistle of his engine was still blasting away when the water hit the yards. There was a sixteen-stall roundhouse in the yards, along with machine shops, 33 locomotives, a lot of rolling stock, and the two passenger trains. The flood smashed everything. The roundhouse was crushed, as one onlooker said, “like a toy in the hands of a giant.” The passenger trains were ripped apart; a few cars caught fire; others swirled about, rolling over and over in the onslaught. Twenty-two of the passengers were killed. Now, railroad cars, rails, ties, locomotives weighing as much as eighty tons, and quite a few human corpses were part of the tidal wave. Woodvale got it next. Woodvale

It was now not quite an hour since the dam had given way. The rain was still coming down, but not so hard; and the sky was not so dark as it had been. In Johnstown, many people thought the worst was over; the water in the streets even seemed to be going down some. At ten minutes after four, the flood hit Johnstown. For years afterward, survivors of the Johnstown flood would talk and write about the sight of the wall of water coming down on the city, and about the sound it made. Over and over, they would describe how it “snapped off trees like pipe stems” or “crushed houses like eggshells” or picked up locomotives (and dozens of other enormous objects) “like so much chaff.” But what seemed to make the most lasting impression was the cloud of dark spray that hung over it. “The first appearance was like that of a great fire, the dust it raised,” wrote George Swank, editor of the Tribune. Another eyewitness, a Civil War veteran, saw it as “a blur, an advance guard, as it were, a mist, like dust that precedes a cavalry charge.” One man’s first reaction was “that there must have been a terrible explosion up the river, for the water coming looked like a cloud of the blackest smoke I ever saw.” The sound, more often than not, was compared to thunder. Many spoke later of how the water roared, how houses shuddered. One man said the water sounded like the rush of an oncoming train. And another said, “And the sound. I will never forget the sound of that. It sounded to me just like a lot of horses grinding oats.” The devastation and drowning of Johnstown took about ten minutes. For most people, those were the most desperate minutes of their lives as they snatched at children and ran for high ground, clinging to rafters, window ledges, anything, as their houses were smashed to kindling or wrenched from their foundations. But there were hundreds, on hillsides, on rooftops, in the windows of tall buildings,

"… In a moment, Johnstown was tumbling all over itself; houses at one end nodded to houses at the other end and went like a swift and deceitful friend to meet, embrace, and crush them. Then, on sped the wreck in a whirl, the angry water baffled for a moment, running up the hill with the town and the helpless multitude on its back, the flood shaking with rage, and dropping here and there a portion of its burden—crushing, grinding, pulverizing all. Then back with great frame buildings, floating along like ocean steamers, upper decks crowded, hands clinging to every support that could be reached, and so on down to the great stone bridge. …" The great stone bridge was the seven-arched bridge that still carries the Pennsylvania railroad over the Conemaugh below the Point. The bridge held because it was not struck by the full force of the flood. Had it been, it would have gone just like everything else. But when the water smashed past the city, it plowed into the side of a mountain before it veered off downstream toward the bridge. The mountain took the brunt of the blow. Within minutes, the debris began building at the bridge. Trees, boxcars, factory roofs, hundreds of houses and hundreds of human beings dead and alive, and hundreds of miles of barbed wire were driven against the stone arches, creating a new dam which would cause another kind of murderous nightmare. At first, there was a violent backwash that swept up the valley of the Stony Creek as far as a mile and a half, causing tremendous damage all the way. Then, as night came on, fire broke out in the jam at the bridge. Stoves full of live coals dumped over inside mangled kitchens. Oil from a derailed tank car soaked down through the mass. By six o’clock, the whole pile had become a funeral pyre for at least three hundred people trapped inside; it burned, Mr. Swank wrote, “with all the fury of the hell you read about—cremation alive in your own home, perhaps a mile from its foundation; dear ones slowly consumed before your eyes, and the same fate yours a moment later.” It would be three days before the fire was put out. That night, the attorney Horace Rose lay in pain listening to the crush of buildings as they settled into the water, and he watched the eerie light that came from the burning debris. He was among the lucky. He had survived the flood. The house in which he and his family awaited it had been one of the substantial brick homes of Johnstown that collapsed in an instant under the weight of the flood, instead of floating off down stream. His side was caved in by falling timbers; his shoulder was dislocated, his

J. L. Smith, a stone mason, lived in a frame house on Stony Creek Street. That morning, when the creek started over its banks, he had rushed his wife and three children across town to the safety of Hulbert House, Johnstown’s new four-story brick hotel. He then went home again. Smith and his house survived the flood. His wife and children were crushed to death when Hulbert House collapsed almost the instant it was hit by the flood. In all, some sixty people had sought shelter in the substantial-looking hotel, thinking it about the best place in town to ride out the storm. More people died there than in any other building; fewer than a dozen got out alive. Gertrude Quinn was the six-year-old daughter of James Quinn, who, with his brother-in-law, ran one of the best dry-goods stores in town. The two of them, she later recalled, looked like the Smith brothers on the cough-drop box. Her father was also one of the people who had been openly worried about the dam for some time, and especially that morning. If the dam gave way, he told his family, not a house in town would be left standing. The Quinns lived in a three-story brick house newly built at the corner of Jackson and Main. When the flood bore down on the city, Gertrude’s aunt, convinced that the house was safer than any hillside, rushed the child to the third floor, despite the father’s shout to “run for your livesl” Ih the third-floor nursery, while her aunt prayed, Gertrude fixed her eyes on the interior of her playhouse, the tiny furnishings of which she would remember in sharp detail the rest of her life. When the flood struck, the big brick house gave a violent shudder. Plaster dust crashed down. The walls began to break up, and suddenly, the floorboards in the attic burst open and yellow water gushed through. Young Gertrude sprang into action. Somehow, she managed to swing herself up and out of the building through an opening in the roof, leaving her aunt, a nurse, and an infant cousin behind. Within seconds, the house was gone, and everyone in it. The next thing she knew, Gertrude was whirling about on a muddy mattress that was buoyed up’ by debris. She screamed for help. A dead horse slammed against her raft, then a tree.

Then she passed close to the roof of a big building crowded with people. She called to them, and a man started up to help her. The others tried to stop him, it seemed, but he pushed away from them and jumped into the powerful current. His head bobbed up, then went under again. Several times more, he went under. Then he was hoisting himself up over the side of her raft and the two of them were fast on their way toward the stone bridge. Farther on, on the hillside, two men with long poles were carrying on their own rescue operation. Seeing Gertrude and her companion, one of them called out, “Throw that baby over here to us.” The child came flying through the air across about ten feet of water and landed in the arms of George Skinner—”a gallant colored fellow,” he would be described as later on. Gertrude’s savior on the raft was a strapping, square-jawed mill worker named Maxwell McAchren. Maxwell lived to tell his tale and became one of the flood’s bona fide heroes. For years afterward, Gertrude’s father took special pleasure in having Maxwell drop by each Fourth of July to elaborate on his deed. And, as Gertrude later wrote, “there was usually a five-dollar bill forthcoming with which Maxwell celebrated.” The Reverend David Beale, pastor of the Presbyterian Church, was at home in the Lincoln Street parsonage, working on his sermon for Sunday, when the flood hit Johnstown shortly after four. The reverend grabbed the family Bible, his daughter grabbed the canary cage, and his wife switched off the natural gas, all in the brief instant they had to turn from the window and get upstairs. By the time they got to the second-floor landing, the water was up to their waists. As they reached the third floor, a man washed in through the window. “Who are you? And where are you from?” Beale shouted. “Woodvale,” the man gasped. He had been carried down on a roof over a mile and a half. Thoroughly expecting to be at any minute “present with the Lord,” Beale led the group in prayer and read aloud from the Bible, his voice shouting against the noise of the flood: "God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble. Therefore will not we fear, though the earth be removed, and though the mountains be carried into the midst of the sea. …" There were ten people in the attic, counting the newcomer and others who had been downstairs visiting before the flood hit. Soon after, Beale helped save several more friends and their children by pulling them in through the window. But there

Alma Hall was made of brick. It was four stories tall. It faced the town square, and it still does. It was one of the buildings in Johnstown that withstood the impact of the flood and held through the long night after. And well that it did, for there were several hundred people in Alma Hall that night. The rooms and corridors of the upper three floors were pitch dark and filled with the crying of scared children, the moaning of the wounded, and a lot of fervent praying. From outside came the sounds of nearby buildings cracking up and caving in. To prevent panic, an Alma Hall government was quickly set up, with the Reverend Beale in charge of one of the floors. All whiskey was confiscated and the use of matches strictly forbidden because of the likelihood of a natural-gas leak in the basement. There was no light, no food or water. There were no blankets, no dry clothes, and no medical supplies. Nor was there any assurance whatsoever that the whole building would not crack apart and bury them all. Among Alma Hall’s refugees was John Fulton, the same engineer who had reported to Daniel Morrell on the structural shortcomings of the South Fork dam. It was, in Mr. Beale’s words, “a night of indescribable horrors.” But everyone in Alma Hall came out alive. In the early morning, before dawn, on Saturday, June 1, thousands of people on the nearby hillsides watched the wreckage of Johnstown begin to emerge from the half light. Cold and hungry, many of them badly injured, they huddled under dripping trees or stood along narrow footpaths ankle deep in mud. At the Frankstown Road hill, some 3,000 people were gathered. The sky overhead was a soft, spotless blue. It was going to be a magnificent day. Few of them had had any sleep. The sounds from below had been too horrible through the night. Some of the Civil War veterans were saying it was worse than anything they had ever been through before. Then, too, there was a kind of grim fascination in seeing fire and water together where a city ought to be. Little Gertrude Quinn said it was like watching ships burning at sea. But just how bad the damage had been, no one really knew until the sun was up. Almost any hill around Johnstown offers a panoramic view of the whole

The water level had gone down a great deal since the night before. A big embankment along the Pennsylvania tracks near the bridge had given way and the water had raced through down past the Cambria Works, carrying a number of people to their death. There had been heavy damage below the bridge at the Cambria Works and at Cambria City, Morrellville, and Sang Hollow, but it was nothing compared to what had happened above. Johnstown was a sea of muck and rubble and corpses. There were still several buildings standing where they had been. The Methodist Church was there and the B&O station; so were Alma Hall, the Presbyterian Church, and the big brick office of the Cambria Iron Company. But all around them, the wreckage was stacked ten, twenty, thirty feet high. Houses were dumped over every which way, broken and scattered. Dead animals and pieces of dead animals were strewn everywhere. At the stone bridge, a good part of what had been Johnstown lay in a burning heap. The flood and the night that had followed, for all their terror and death and destruction, had had a certain terrible majesty. Many people had thought it was Doomsday, Judgment Day, the Day of Reckoning come at last. It had been awful, but it had been God Awful. This that lay before them now was just ugly and sordid and heartbreaking, and already it was beginning to smell a little. The survivors began coming back down into town almost immediately. They slogged through the mud and water looking for lost wives or fathers or infants. They picked among the wreckage and they began picking up the dead. Morgues were set up in the Presbyterian Church, in the Adam Street and Millvale schoolhouses. Bodies were numbered and identified, if that was possible. Many of them were in ghastly condition, stripped of their clothes, limbs torn off, battered, bloated, some already turning black. About one out of three was never identified beyond an entry in the morgue log books. … No. 173. Unknown. Male. About 50. Large broad face. Dark hair. Full face. German look. Sandy mustache and goatee. … No. 181. Unknown. Female. Age 45. Height 5 feet 6 inches. Weight 100. White. Very long black hair, mixed with gray. White handkerchief with red border. Black striped waist. Black dress. Plain gold ring on third finger of left hand. Red flannel underwear. Black stockings. Five pennies in purse. Bunch of keys. … No. 182. Unknown. Male. Age five years. Sandy hair. Checkered waist. Ribbed knee pants. Red undershirt. Black stockings darned in both heels. For the living, the problems to be faced immediately were enormous and critical. There was virtually no food or medicine. Thousands were homeless; there was no gas, no electric light. Fires were burning everywhere, and no one knew when a gas main might explode. With the sun growing warmer every hour and the dead all over the place, the threat of an epidemic was

But the first word of the disaster got to the newspapers in Pittsburgh and so to the outside world by way of the railroad and, ironically enough, by way of a member of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. Robert Pitcairn, superintendent of the Pennsylvania’s Pittsburgh Division, had been on a train that had been stopped below Johnstown on the afternoon of the flood. He had been on his way to Lilly, to see about the landslide there. When he saw the debris and corpses tearing by in the swollen Conemaugh, he sent a cable to the Pittsburgh Commercial-Gazette that Johnstown had been wiped out and that help should be organized immediately. A newspaper was the first to hear, and newspapermen from Pittsburgh and numerous other cities were the first of what would become an army of outsiders to head for Johnstown. Within two hours of receiving Pitcairn’s message, the Commercial-Gazette had a special train headed for Johnstown. Other Pittsburgh papers were quick to do the same. The trains got no farther than Bolivar, a coal town on the Conemaugh seventeen miles west of Johnstown. But the reporters got off and began hiking along the flooded tracks. Most of them gave up and spent the night in the little railroad crossing of New Florence, where they could see a blood-red glow in the sky from the fire at the bridge fourteen miles away. But a few pushed on over the mountains to arrive in Johnstown about dawn the next morning. Within two or three days, the city was crawling with reporters, writers, artists, and photographers. This was the biggest story since the murder of Abraham Lincoln, and virtually every major newspaper and magazine in the East and Midwest was covering it. One of the contingent assigned by the Philadelphia Press was Richard Harding Davis. He was a cub reporter, twenty-five years old, strikingly handsome, and just as sure as he could be that he would one day be the world’s most famous newspaper correspondent. Davis was too late to file straight news stories, so he concentrated on human interest, instead. He wrote of walking over thousands of spilled cigars, of a pretty relief worker with not a hair on her head astray, and of finding the body of the one man in Johnstown who had drowned in a jail cell. The man had been locked up for over-celebrating on Decoration Day. The first stories to come out of Johnstown were full of horror and staggering statistics and they sold a staggering number of newspapers. On Saturday and Sunday, the reports were somewhat vague about how many people had been killed, with estimates ranging from 1500 to 6000. But by Monday, the New York World claimed 10,000 people were dead in “the Valley of Death.” On Tuesday, the headlines had the count up to

Victorian sentimentality had a heyday, and so did the publishers. One Pittsburgh newspaper was selling its flood editions so quickly that it had to reduce its page size to keep from running out of paper. In New York, the Daily Graphic sold 75,000 extra copies per day. Magazines got out special editions. Books were dashed off in a few weeks and rushed to the printers. But the real importance of the journalists’ handling of the story was the fantastic effect it had on the relief of the stricken city. The sympathy aroused by the newspaper accounts brought on a rush of popular charity greater than the country had ever seen. The first organized relief began less than twenty-four hours after the disaster, when a mass meeting was called at the old city hall in Pittsburgh. Robert Pitcairn got up and talked about what he had seen. A committee was named to collect clothes and supplies, and then there was a call for contributions. At the front of the hall, two men using both hands took in $48,116.70 in less than an hour. “There was no speech- making,” a reporter later wrote, “no oratory but the golden eloquence of cash.” In one week, $ 600,000 was collected in New York. Boston gave $94,000 and Kansas City, $12,000. Nickels and dimes came in from school children and convicts. Churches sent $25, $50, $100. Jay Gould sent $1000; John Jacob Astor, $2500. The New York Stock Exchange gave $20,000. Tiffany’s gave $500; Macy’s, $1000. Money came from the Sultan of Turkey, the Lord Mayor of Dublin, and Cupola, Colorado. The Pennsylvania Railroad gave $30,000. In all, over $3,000,000 was donated, and this does not include the goods of every kind that came in by the trainload. The relief trains began arriving on Saturday night. One from Pittsburgh carried nothing but coffins and fifty-five undertakers. Lumber came in by the carload, and flour, furniture, barrels of quicklime and embalming fluid, crates of bread, beans, cheese, candles, coffee, tea kettles, shoes, blankets, mattresses, and soap. Wheeling, West Virginia sent a whole carload of nails. The state militia moved in on Sunday morning, pitched their tents, and took over the running of the city. Their commander was Daniel Hartman Hastings, a placid-faced minor power in Pennsylvania politics who had received his only military experience during the railroad

The cleanup was taken on by everyone able to lend a hand and by a construction crew of 6,000 men that came in from Pittsburgh. A dynamite expert named Kirk was also brought in to see what he could do with the jam at the bridge, which covered almost sixty acres. All attempts to pull loose the debris had failed. Locomotives and a steam winch had been tried, and a gang of lumberjacks from Michigan had done their best, but had made no progress. Then, for several days, the valley shook with the roar of Kirk’s dynamite as great gaps were blasted through the entanglement of houses and barbed wire and charred corpses. Another work crew from Pittsburgh was brought in by one of the most illustrious characters of the time, Captain Bill Jones, the tough, headstrong boss of Carnegie’s gigantic Edgar Thompson Works in Braddock, and quite possibly the greatest steelmaker of all time. Jones had learned the business in Johnstown, working for Daniel J. Morrell at the Cambria Works. Now he was back in town with three carloads of supplies and 300 of his men; he paid all his expenses himself. But the outsider who stirred up the most action and the most talk was a stiff-spined little spinster in muddy boots who came in on the B&O early Wednesday morning leading a band of fifty men and women. Clara Barton and her newly organized American Red Cross had arrived at their first major disaster. Clara was sixty-seven. She had been through the Civil War, the Franco-Prussian War, and several nervous breakdowns. She had not a gray hair on her head. She stood five feet tall; she took what little sleep she needed on a hard, narrow cot and had no use for demon rum, bumbling male officials, or, for that matter, anyone who attempted to tell her how to run her business. She set up headquarters inside an abandoned railroad car, using a packing box for a desk. She worked almost around the clock, directing hundreds of volunteers, distributing blankets, clothes, food, and half a million dollars. Temporary housing was put up according to her specifications, as was a Red Cross “hospital.” Her work kept her on the scene for five months. When she left, it was with all sorts of official blessings and thanks. Glowing editorials were written; a diamondstudded

But, along with the press, the Army, the work gangs, and the Red Cross, there was also a handful of petty crooks and crackpots, plus a goodly number of old-fashioned American sightseers who turned up in Johnstown. A few small-time crooks lined up with the flood victims to collect whatever the Red Cross happened to be handing out at the moment, or grabbed what they could from among the debris. One or two suspicious-looking characters were nabbed before they had a chance to do much of anything and were quickly hustled out of town. The crackpots were largely of the religious-fanatic sort and included one gaunt prophet from Pittsburgh known as “Lewis the Light” who wore nothing but long red underwear and passed out handbills that said, among other things: "Death is man’s last and only Enemy. Extinction of DEATH is his only hope. Your soul, your breath, ends by death. Whew! Whoop! We’re all in the soup. Who’s all right? Lewis, the Light." The sightseers arrived on excursion trains that chugged in along the B&O on weekend mornings. On Sunday, June 23, several hundred arrived, turned out in holiday attire and carrying picnic baskets. They strolled about, got in the way, and infuriated nearly everyone except a few enterprising Johnstowners who began selling official Johnstown Flood relics: broken china, piano keys, horseshoes, buttons, even bits of board or brick. Meanwhile, the search for corpses went on. Every day, a few more were uncovered. And so it continued until well into the fall. In October, twenty-six bodies were found between Johnstown and Ninevah, seven miles down the Conemaugh. Estimates were made on the total property damage (about $17,000,000), and life began to return, more or less, to normal. Cambria Iron got part of its mill back into operation by July. The city still smelled terrible; thousands of people were still living in tents or rudely built huts on the hillsides; but by October, the schools and banks were open again. Johnstown was back in business. As for the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, all was quiet along the huge mud flat that had been Lake Conemaugh. Grass was starting to grow along the creek that worked its way through the center of the old lake bed, and deer left tracks where they came down to drink. Up close to where the shoreline had been, the big frame clubhouse and the summer houses stood silent and empty, with some of their windows smashed. After the disaster, the club members never came back again. In July, the property was divided up and sold at a sheriff’s sale for $600 a parcel. But the club members and the part their dam had played had not been forgotten. The outcry began almost immediately after the disaster. By Sunday, June 2, the newspapers were proclaiming that the “death dealer” was

On June 7, just one week after the flood, the coroner of Westmoreland County held a mass inquest on the 218 bodies that had been taken out of the Conemaugh River up to that time. Officials had gone to inspect the ruins of the dam and to talk to anyone in the neighborhood who claimed to know anything about its construction or about the people who were supposedly looking after it. There were, not surprisingly, plenty who were willing to talk. When the coroner’s jury met, the verdict was “Death by violence due to the flood caused by the breaking of the South Fork Reservoir.” The first damage suit was filed in August in Pittsburgh, where the club had been originally incorporated in 1879. Nancy Little and her eight children brought suit against the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club for $50,000 for the loss of her husband, John Little. The club members entered a voluntary plea of not guilty, claiming that the disaster had been a “visitation of Providence.” The jury agreed. There were other suits later on, but the verdicts were the same. Not one nickel was ever collected through damage suits against the club or any of its members. Generous donations to the relief fund were made by club members, including $10,000 from the Carnegie companies, and at one point, they offered the clubhouse as a home for flood orphans, but the offer was turned down. How the damage cases would have gone had they been tried in Johnstown, instead of Pittsburgh, or by today’s standards, are questions one cannot help asking. It is quite possible that those Pittsburgh fortunes might have been substantially reduced. In time Johnstown recovered. The flood was talked about for years and described in a dozen or so personal memoirs and “official histories” done by survivors. The legends grew, including a fine one about a man named Daniel Peyton, the so-called Paul Revere of the Conemaugh, who came charging down the valley on a big steed warning everyone to run

Today, there is talk in Johnstown about building a tourist center on top of one of the city’s highest hills, with a cyclorama, recorded lectures, diagrams, and so forth. By the summer of 1967, the National Park Service plans to open a fifty-five-acre Johnstown Flood National Memorial at the site of the old dam. The ends of the dam, enormous, steep-sided earth mounds, still stand among the trees up the valley above South Fork. A few years ago, a group of local citizens cleared the brush off the tops of the mounds, put down gravel walks, set out park benches, guard rails, a sign, and two flag poles. There is also a place to park just off the narrow road that goes through the cut in the rocks that was once the spillway. The old lake bed is now nearly covered by woods. You look out over the tops of tall trees that appear to have been there always, and a rocky creek that is the same new-baseball-glove color as the rivers in Johnstown. Beside the creek, a railroad track runs up past the town of St. Michael to the coal mines near Windber. When the coal cars roll by below, they look very small. The clubhouse and a number of the cottages are also still standing, about a mile away in St. Michael, a town of about 1100 people. The clubhouse is now a hotel, a gray, weathered old ark with tin Seven-Up and Mail Pouch signs nailed to it. There is a big bar inside, just off the front porch, where unemployed coal miners sit drinking and talking. The room, like the others near it, has a high ceiling, dark wood paneling, and an elaborate brick fireplace that looks big enough to roast an ox in. Most of the summer houses have been remodeled. They are mixed in with the flat-faced frame row-houses of St. Michael. But there are a few that, except for paint, look much as they did, three stories tall, with long French windows, front porches, some stained-glass and gingerbread. Nearly all the men who sit on the porches are living on relief, and many of them are sick with silicosis, a lung disease caused by inhaling coal dust over a long period of time. They spend some of their time down at the hotel bar; they work in small vegetable gardens out back; or they just sit there on their porches and look