Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November/December 2022 | Volume 68, Issue 6

Authors: Bill White

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November/December 2022 | Volume 68, Issue 6

Editor’s Note: Pres. George Washington urged future leaders to pay off government liability, rather than “ungenerously throwing upon posterity the burdens which we ourselves ought to bear.” But, since 2000, politicians of both parties have added $25.5 trillion to the national debt, according to the U.S. Treasury. We asked Bill White, the former mayor of Houston and Chairman of Lazard Houston, to provide a look at the history of federal debt and the principles that once guided our political leaders. Mr. White is the author of the much-praised book, America’s Fiscal Constitution: Its Triumph and Collapse.

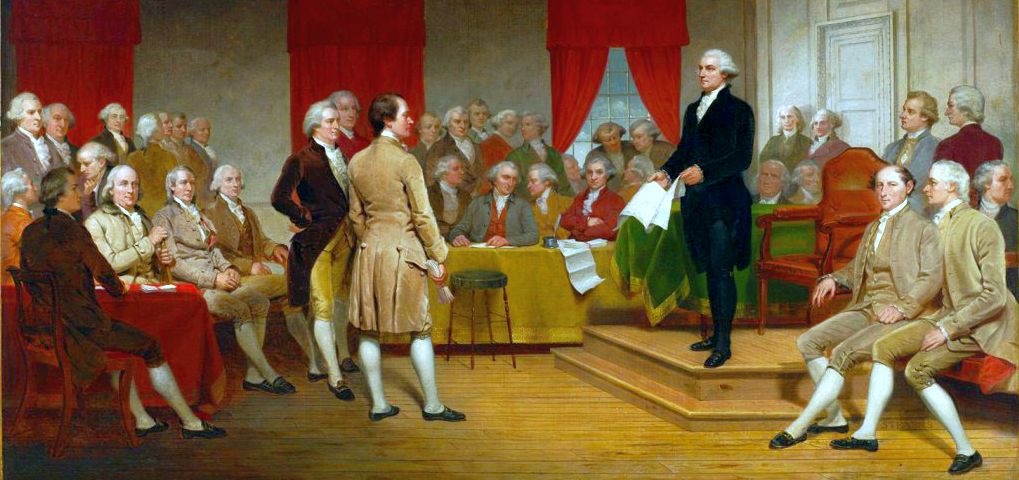

In the years following the American Revolution, George Washington worried that debt from the war remained unpaid. The retired general likened the financially impotent Confederation government to a “house on fire” being “reduced to ashes” while politicians debated “the most regular mode of extinguishing” the blaze.

James Madison and Alexander Hamilton shared Washington’s concern about the repayment of federal debts from the war. In August 1786, delegates from five states gathered at Mann’s Tavern in Maryland to coordinate the taxation of imports among the states, which were still largely independent. While there, Madison and Hamilton called for a meeting of the most influential citizens in each state to come together to devise a plan for repayment of the Confederation’s debt. Hamilton noted that resolution of that financial issue might require “a correspondent adjustment of the other parts of the Federal System.”

The following year, Washington agreed to attend and chair a meeting of fifty-five delegates to plan for the reduction of debt. They created a new nation. Their proposed Constitution formed a federal government with the power to tax and spend. Thomas Jefferson, reading the document in Paris, asked Madison to devise an amendment that would prevent future American leaders disguising the cost of government during their time in office through borrowing. He understood that leaders would be tempted to borrow to enhance their short-term popularity, while burdening a future generation by encumbering future federal tax revenues with debt.

Madison realized that borrowing could be necessary during future emergencies and that “principles based on experience” would be a more practical fiscal constraint than a written formula based on “theory.” Those principles would amount to an informal constitution, similar to the British constitutional norm prohibiting taxation without representation. Accordingly, Madison proposed that principles limiting the federal use of debt should be “clearly visible to the eye of the ordinary politician.”

In the nation’s first

For almost 200 years, the federal government borrowed only for those four purposes. Until the Cold War that followed World War II-era borrowing, federal leaders used surplus tax revenue to steadily retire debt after emergency borrowing. Occasionally, the federal leaders authorized debt when revenues fell short of earlier estimates. But, in the absence of well-defined emergencies, for two centuries, no president or leaders in Congress endorsed borrowing as a continuing means of funding routine annual outlays.

Leaders of the early republic devised specific practices to avoid incurring debt, apart from well-defined emergencies. Those practices included clear accounting; “pay-as-you-go planning” that linked spending and tax policies; and the use of trust funds to pay for specific activities in amounts confined to dedicated revenues. In addition, Congress approved debt only for purposes specifically authorized by legislation.

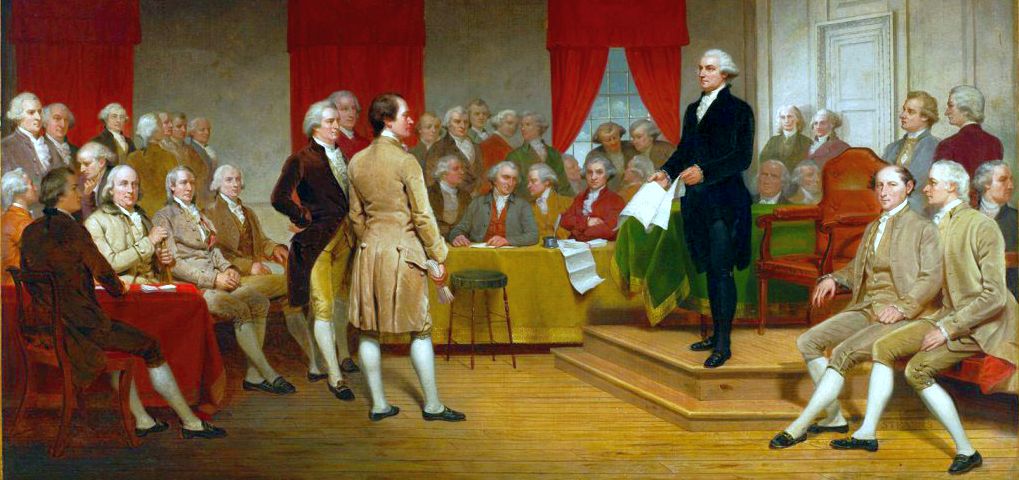

Albert Gallatin, Secretary of Treasury during the Jefferson and Madison administrations, devised each of those practices. They were institutionalized and endured for over a century and a half after Gallatin left the Treasury.

To be clear, during the nation’s early history, citizens did not enjoy paying taxes. Then, as now, most citizens wanted more services from the federal government, but were reluctant to be taxed to pay for them. They were even more loath to incur federal debt, a form of deferred taxation. Most voters endured other hardships to create a better future for their children. Farmers and merchants realized that private investment could suffer when public debt absorbed relatively more credit. Americans with little formal education understood that government paid for on an installment plan, with interest, could ultimately cost more. And early Americans valued independence from foreign creditors.

In 1836, Americans celebrated when the United States repaid the last of its debts incurred to finance the War of Independence, the Louisiana Purchase, the War of 1812, and the Panic of 1819. The sacrifices of America’s first generation transformed the world’s first modern democracy into the first major debt-free nation. American willingness to reserve its credit for emergencies became a pillar of the nation’s exceptionalism.

Another feature of the informal American

And the United States needed all its credit during the Civil War. It entered that war with $65 million in debt and emerged with interest-bearing debt of $2.3 billion. At the end of the war, Congress resolved, with only one dissenting vote, that the “public debt created during the late rebellion . . . must and ought to be paid, principal and interest.” Treasury Secretary Hugh McCulloch expressed the “ambition of the people of the United States to relieve their descendants of this national mortgage.” He wisely observed that “wars are not at an end, and posterity will have enough to do to take care of the debts of their own creation.”

To minimize Civil War debt, Congress had raised taxes on imports and imposed new ones, including an income tax. As with the War of 1812, the wartime taxes on imports and sales of some products continued after the war. Shortly after the war, the British embassy in Washington reported with admiration that “the majority of Americans would appear disposed to endure any amount of sacrifice, rather than bequeath a portion of their debt to future generations.”

Eighty-five percent of eligible voters cast ballots in the election of 1876, in which Democratic Samuel Tilden won the popular vote and would have won the electoral college if Republicans had not replaced the electors designated by three states. Bitter partnership characterized that era. Yet, reflecting a bedrock national consensus, Tilden and the eventual winner by one electoral vote, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, both strongly supported spending less than available revenues, with a surplus available for debt reduction. To reduce the interest rate on the outstanding Civil War debt, the United States pursued a non-inflationary, though often-painful monetary policy.

In 1880 alone, the United States paid down more than $200 million in debt, four times more than the total federal budget before the Civil War and more than the total amount that all banks had been willing to loan the government at the outset. The following year, interest on U.S. debt fell to the same level as British debt, which had commanded the lowest interest in the world in the preceding century.

Reduction of federal debt made more savings available to the private sector. That credit, combined with high rates of immigration and technological progress, led to an explosive growth in industrial production during the

The federal government did not incur additional debt for 37 years following the Civil War. In fact, between the end of the Civil War and American entry into World War I in 1917, the nation borrowed only during several economic downturns and to finance the Spanish-American War and the Panama Canal.

Americans could precisely identify the emergency origin for all outstanding bonds when the United States entered World War I. Congress earmarked each outstanding bond issue for specific purposes — refinancing the remaining Civil War debt and funding the Spanish-American War and the Panama Canal. By entering World War I with a pristine balance sheet — debt less than two percent of the gross national product — and implementing a vast new income tax system to reduce borrowing, the United States emerged from World War I as the world’s greatest financial and monetary power.

To reduce the burden of debt at the conclusion of that war, Congress retained most of the wartime tax system and created a White House Budget Bureau responsible for preparing an official, presidential budget. Charles Dawes, the influential new budget director, crafted budgets in the same manner as Albert Gallatin had during the early republic. Spending — including amounts earmarked for the reduction of debt from the war — was limited to estimated revenue. By 1929, debt had been slashed by a third of the amount outstanding a decade earlier. And, despite this lack of “fiscal stimulus,” the American economy boomed in the 1920’s.

The federal government borrowed extensively for sixteen years, from the onset of the Great Depression through the end of World War II. Yet President Franklin Roosevelt and congressional leaders consistently and repeatedly championed the ideal of a balanced budget during normal times. Federal budgets sought to confine “normal” spending within tax revenues, while maintaining separate budget categories for spending for Depression-related “relief” and the wartime military.

A poll in 1939 asked Americans: “If you were a member of the incoming Congress, would you vote yes or no on a bill to reduce federal spending to a point where the national budget is balanced?” A lopsided 61.3% said yes; only 17.4 percent replied no. By then, national output and income had been restored to 1928 levels, though unemployment — particularly among unskilled workers — remained higher.

The Great Depression highlighted the vulnerability of older, retired Americans. President Roosevelt’s Committee on Economy Security recommended “some safeguards against misfortunes which cannot be wholly eliminated in this man-made world.”

Roosevelt endorsed the idea of a social insurance paid for “by contribution, rather than an increase in general taxation,” in part, as a means to allow future federal governments to “quit this business of relief.”

The idea of a self-funding, debt-free program of social insurance had been espoused by economists and reform-minded elected officials in

Initial Social Security pensions could not help the six percent of Americans already over sixty-five who had no history of contributions during the program’s early years. When Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins argued for more immediate benefits, with the actuarial balance maintained as needed with general revenues, Roosevelt curtly replied that it would be “dishonest to build up an accumulated (pension fund) deficit for the Congress of the United States to meet in 1980.”

By the late 1930s, many economists believed that federal fiscal restraint had prolonged Depression-related unemployment. In hindsight, few doubt that additional debt-financed spending would have further stimulated the economy. And the Great Depression discredited the theory that federal budgets should balance as revenues fell in order to revive the economy by restoring “business confidence.” But soon, after Pearl Harbor, the federal government needed every single dollar of available credit supported by private savings and the Federal Reserve's monetization of debt.

President Roosevelt did not mince words in his national address when the U.S. entered World War II: “War costs money. That means taxes and bonds, bonds and taxes.” Adolf Hitler disparaged American racial diversity and asked how “a state like that can hold together — a country where everything is built on the dollar.” He soon found out. In 1942, the German sphere of control in Europe had a population and national income greater than those of the United States. That year, the United States produced three times as many aircraft and tanks as the European Axis powers.

That achievement entailed massive federal spending, borrowing, and the creation of a new federal tax system. The Revenue Act of 1942 vastly expanded the reach of federal personal income taxation and it raised corporate rates; soon, federal revenues rose to almost a fifth of the national income. Despite frequent shifts in the nation’s political balance in the 80 years since that Revenue Act, federal personal income tax revenues have generally remained in the range of 7-9 percent of national income.

Many economists and Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace predicted that the sharp curtailment of post-war federal spending would result in massive unemployment, without large, stimulative new domestic spending. They were wrong.

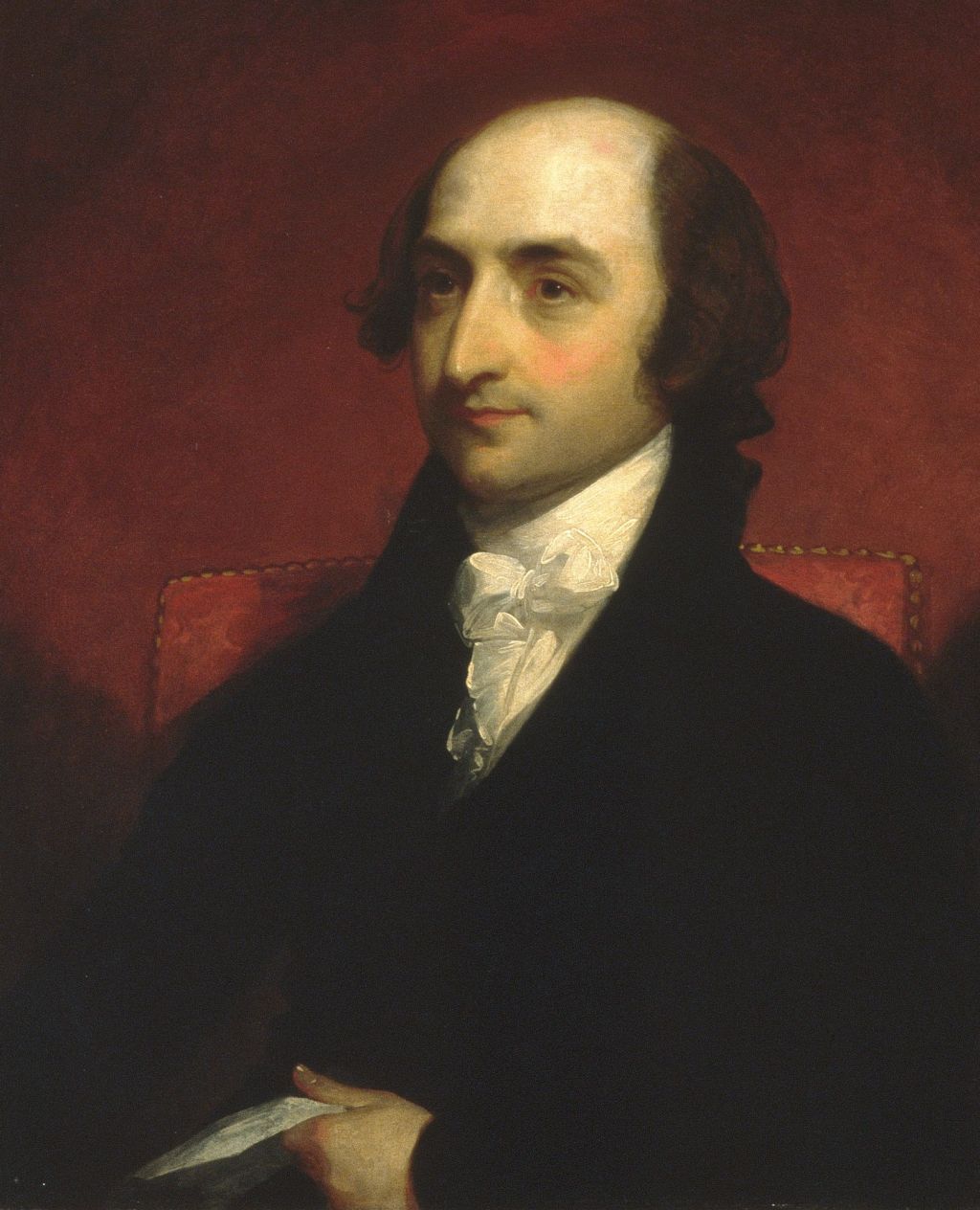

President Harry Truman embraced balanced budgets crafted in the same manner as had been implemented during the Jefferson administration, and as was used to limit debt in the aftermath of the War of 1812, the Civil War, and World War I. Truman’s Budget Bureau estimated the federal revenues, subtracted interest on the federal debt, and then allocated the balance between military and domestic spending. Senator Robert Taft, recognized as “Mr. Republican” for his lead in articulating GOP policy, agreed with this budget approach, while arguing for lower taxes and a corresponding reduction in military spending.

Truman and Taft were a study in contrasts. Truman never attended college; Taft graduated near the top of his class at Yale and Harvard Law School. Truman grew up in a modest home in a small Missouri town; young Taft lived in the White House during his father’s presidency. Truman had never been considered a serious candidate for the president until well after he assumed office following the death of Franklin Roosevelt; Taft was considered as a potential GOP nominee every four years following his election to the Senate in 1938. Yet they agreed that routine federal spending should be financed entirely with tax revenues.

This “pay-as-you-go” consensus forced federal leaders to confront and resolve difficult budget trade-offs. In the partisan atmosphere of the summer of 1950, federal leaders made two hard choices on federal pensions for older Americans and a global security umbrella: Those budget choices shaped all future federal budgets and illustrated the strength of the American fiscal tradition.

Because of the priority of war-related spending and income taxation, neither the minimum Social Security pension nor payroll taxes had been increased since passage of the legislation in 1935. The minimum old-age pension benefit — $35 a month — was not enough to live on. So, each year, with little dissent, Congress approved larger grants to states for public assistance, or “welfare,” which came to support a fifth of all Americans over 65. That budget challenge would get worse every year and required a source of revenue other than personal and corporate income taxes, as these rates were already extraordinarily high.

Bipartisan leaders of the House Ways and Means Committee crafted amendments to the Social Security act that extended pension coverage to most American workers, increased the minimum benefits by 70 percent, raised payroll taxes, and scheduled future payroll tax increases. That bill passed the House in June 1950 on a 333-14 vote, and the Senate approved it by 81-2. From that day on, a system of pension benefits, sustained by payroll taxes and without relying on debt, allowed most Americans to retire with a measure of dignity.

North Korea invaded South Korea five days after final passage of the Social Security Act Amendments of 1950, virtually ending the post-World War

During the three decades after 1970, every presidential nominee and the Congressional leadership of both parties embraced the ideal of balancing the budget, which led to fierce annual battles over budget priorities.

During the 1970’s, federal-funds outlays — spending apart from the dedicated trust funds — rose by about one percent of national income, while federal-funds revenues (principally, individual and corporate income- tax collections) did not. The United States sought to obtain “full employment,” while many businesses faced increased foreign competition, consumers grappled with higher inflation, and the Soviet Union remained belligerent. Each year, Congress found it difficult to match federal spending and tax revenues, but balanced budgets remained the explicit goal of leaders in both parties. By 1979, most state legislatures passed resolutions to trigger a balanced-budget constitutional amendment, and Congress reformed its budget procedures to bind committees to overall spending and revenue goals.

Some commentators mark the 1980s as a turning point in the political consensus for balanced budgets during normal times, since a tax cut and increase in military spending enacted in 1981 preceded a succession of deficits. Yet Congress cut tax rates that year based on estimates that the budget would quickly balance, as forecasters believed the economy would steadily grow while inflation pushed taxpayers into higher brackets. Instead, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates, subduing inflation while precipitating a recession.

Higher federal interest payments and Cold War outlays caused federal spending to increase more quickly than federal revenues during the Reagan presidency. Each year, Congress engaged in fierce debates about how to best reduce the resulting deficits, and it ultimately began to impose spending caps triggered by annual deficit-reduction goals.

George H. W. Bush famously insisted, “Read my lips: no new taxes” at the 1988 Republican National Convention. He negotiated with a Democrat-controlled Congress for a budget that would meet his pledge, but finally agreed in 1990 to a compromise that limited spending and increased several existing taxes. In the general election, Democratic nominee Bill Clinton, running as a moderate, pledged to balance the

With increasing public pressure for fiscal discipline, during the 1990s, President Clinton and House Speaker Newt Gingrich both proposed concrete plans to balance the budget, and they compromised to eventually do so.

Debt incurred during the years 1970 to 2000 largely arose from traditional circumstances that justified borrowing — several recessions and an escalation of the Cold War. Control of Congress and the White House was often divided during those decades and leaders of each party embraced the idea of a balanced budget and blamed the other party for failing to do so. When the budget ultimately balanced in 2000, leaders of each party took credit. Even though Congress had struggled to balance the budget for several decades, the consensus ideal of linking spending and revenues survived.

Both presidential candidates in 2000 committed to maintain future projected budget surpluses. And all federal budget leaders then understood that fiscal discipline could help prepare citizens for sharp rises in Medicare payments when the vast Baby Boom generation began to retire in 2010.

But, within 36 months of the 2000 presidential election, the shared commitment of federal leaders to balance the budget, except during emergencies, began to collapse. Congress and the G.W. Bush administration cut taxes while raising spending. For the first time in history, the United States failed to raise taxes during war and actually lowered taxes early during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In 2003, the president and the bipartisan Congressional leadership agreed to an expansion of Medicare financed principally with debt — the first major and permanent new federal domestic program ever financed in that manner. For the first time since outstanding debt had remained from the Revolutionary War, the federal government relied on foreign nations and investors to finance much of the new federal borrowing.

The United States emerged from the second Bush administration with what some call a “structural deficit” — spending, apart from the two ongoing wars, in excess of tax revenues. At the end of that presidency and the beginning of the Obama presidency, in 2008 and 2009, the federal government borrowed for a traditional purpose — federal spending and tax cuts intended to shorten the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression.

But federal leaders had no credible plan to restore the budget balance once unemployment fell and those two long wars ended.

President

During the 2012 presidential campaign, Obama and Republican nominee Mitt Romney presented plans to balance the budget in some distant year, while borrowing aggressively during the next presidential term. In a major speech on the deficit during the 2011 debate over the budget ceiling, Obama described the need to close the gap in Medicare funding for the Baby Boom generation. Neither candidate in 2012, however, proposed ending borrowing to finance rising Medicare.

By 2013, the four pillars of the American fiscal tradition — clear accounting, “pay-as-you-go” budget planning, self-funded independent trust funds, and borrowing for a specific purpose defined by Congress — had fallen into disrepair. Incumbent leaders in each major political party acknowledged the virtue of balancing the budget in the distant future, but denied they had the ability to do so any time soon without impairing economic growth. Many Democrats maligned efforts to bring levels of spending in line with revenues as a form of “austerity.” Republican leaders disparaged efforts to substitute tax revenues for debt as a “job-killer.”

During the 2016 presidential election, GOP nominee Donald Trump promised to “pay off the debt.” Once he took office, with his party controlling both houses of Congress, taxes were cut and spending increased sharply. Then debt-financed spending accelerated at an unprecedented pace after the COVID-related economic slowdown. During Trump’s four years in office, the federal debt rose by $7.8 trillion.

Before 2000, Congressional budget leaders in each party battled each session to promote their tax and spending priorities, with the GOP urging tax policies that favored lower tax rates and higher defense spending and Democrats seeking to broaden the social safety net. The link between federal spending and tax policy forced hard choices between those objectives. When that link broke after 2000, Congressional leaders in each party typically obtained some of what they sought – tax cuts or new spending – financed with debt, in annual budget compromises.

Compound interest is a mathematical miracle for creditors and a curse for debtors. The federal government has borrowed more than it paid in interest for 21 consecutive years. In fiscal year 2021, federal funds revenues — those apart from trust funds and the only funds available to service debt — funded less than half of federal-funds spending. For at least the next several years, forecasters project that a third of all routine federal spending will be financed by borrowing, even assuming substantial economic growth, low unemployment, and no new wars.

By 2027, the total federal debt is estimated

And that assumes no more large spending programs or tax cuts. Assuming that the weighted interest on federal debt is 4%, or only 2% higher than the Fed’s targeted inflation rate, more than $1.2 trillion will be committed each year to interest on the debt. That is more than triple the projected level of federal corporate income tax receipts, and more than half of all federal personal income tax payments last year.

Americans have never enjoyed taxation and have always expected more from government. Accordingly, the political temptation to expand services while substituting debt for taxation has always existed. Jefferson described that risk when he asked Madison to consider some constitutional constraint on borrowing to finance routine federal operations and services. The political consensus concerning the use of debt in only well-defined and extraordinary circumstances survived the Early Republic and remained largely intact until the last two decades. That consensus — effectively an informal constitution — forced federal leaders to weigh the visible costs of taxation carefully and publicly against the benefits of new government responsibilities.

American voters, candidates, and political parties have differed on the proper scope of federal responsibilities since the Early Republic. Until recently, those seeking to limit and even reduce those responsibilities understood that tax-funded spending limits the growth of government by making its cost more palpable. Those seeking to broaden the social safety net or the scope of national security have understood that those activities would be more sustainable when supported by taxation. That led to a broad consensus in favor of linking tax and spending policies.

The federal government can monetize some amount of debt at no net interest cost, as it did by issuing paper currency during the Civil War; by the Federal Reserve’s purchase of some debt to support lower interest rates during World War II; and as it has done more recently to facilitate lower interest rates during the Great Recession beginning in 2008 and the COVID crisis in 2020.

Since the unconstrained monetization of debt poses risks of inflation and higher interest rates, Congress established

For more than two centuries, elected federal officials could give a straightforward and concise explanation of the desired relationship between non-emergency federal spending and tax revenues. Budget-making began with a good-faith estimate of tax revenues based on the level of taxes Congress imposed. Then, federal elected officials debated and resolved the spending priorities in the context of revenues that would balance that year’s budget, or — in the late twentieth century — that could result in a balanced budget within several years.

Today, the link between spending and taxation has been severed. It may have started as a relatively small hole in the fiscal dam in 2001-2003, with debt-funded tax cuts, wars and the expansion of Medicare. Since then, the hole has grown consistently larger. Meanwhile, interest on debt incurred to finance prior federal spending consumes a rising percentage of federal revenues.

Without some well-understood principle defining the level of spending supported by tax revenue, it is difficult to describe a level of excessive spending or inadequate tax revenue. Without a salient goal such as balancing peacetime budgets during low unemployment, what principle can federal elected officials use to justify any level of taxation or limits on spending?

The historic and unique long-term balance between federal spending and taxation contributed greatly to features that made the United States exceptional — increasing savings available for private investment and economic growth; financing a global security umbrella; and supporting monetary discipline that allows businesses and consumers to make better financial plans because all global commodities are priced in dollars.

The United States still has an exceptional role in the world; just ask Ukrainians receiving huge military assistance or the millions of people who seek to emigrate here. The government cannot, however, ultimately defy the laws of supply and demand. The Federal Reserve cannot monetize large amounts of debt without fueling inflation. As, as Great Britain has recently learned, at some point, creditors will require sharply higher interest rates to hold debt by a government that replaces tax revenues with more borrowing. It will be far less painful for the United States to restore fiscal discipline on its own terms earlier, than to have it imposed by creditors

My 2014 book, The American Fiscal Constitution: Its Triumph and Collapse, articulates the hope for a return to fiscal

Jefferson asked Madison to consider how a constitutional amendment might limit debt to some amount that could be repaid by the generation that incurred it. He noted how a monarch might incur debt and borrow further to pay interest during his reign. Jefferson calculated that, after 19 years, at 5 percent interest, the debt would be 2.514 times the amount originally borrowed. He considered placing that burden on the next generation “an act of force, and not of right.”

Obviously, the American economy is far stronger than it was during the early Republic. Part of that strength, one of the pillars of American exceptionalism, arose from principles that limited the historical use of federal debt. Now, the rising use of debt to fund routine federal expenses vindicates Jefferson’s apprehensions. As interest rates rise, while federal debt exceeds the total annual national income, and grows more quickly than national income, our window to balance the budget begins to close. The options of future Americans and their elected federal representatives have begun to narrow.

The United States will, of course, survive its current debt crisis, as it did those following the Revolution, the War of 1812, the Civil War, World War I, and World War II. Many European and emerging markets have survived by borrowing until high interest rates and defaults have stunted their growth and influence.

If the U.S. fails to react promptly to restore fiscal discipline in the same manner as it did during its prior debt crises, will it lose one of the principal pillars supporting its exceptional role in the world?