Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2022 | Volume 67, Issue 4

Authors: Mark Piesing

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2022 | Volume 67, Issue 4

Editor's Note: Mark Piesing is a freelance journalist and the author of N-4 DOWN: The Hunt for the Arctic Airship Italia, from which he adapted this essay.

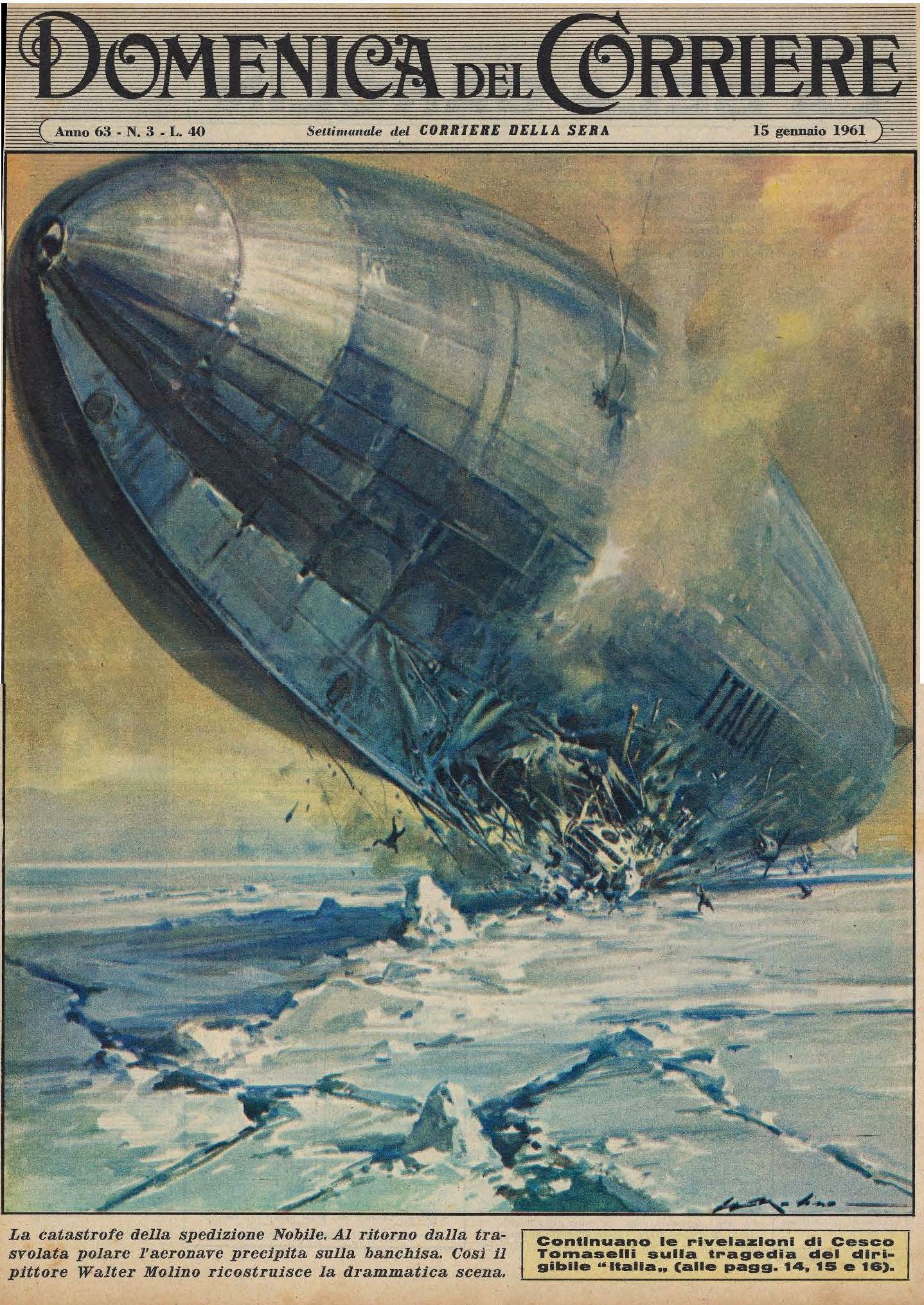

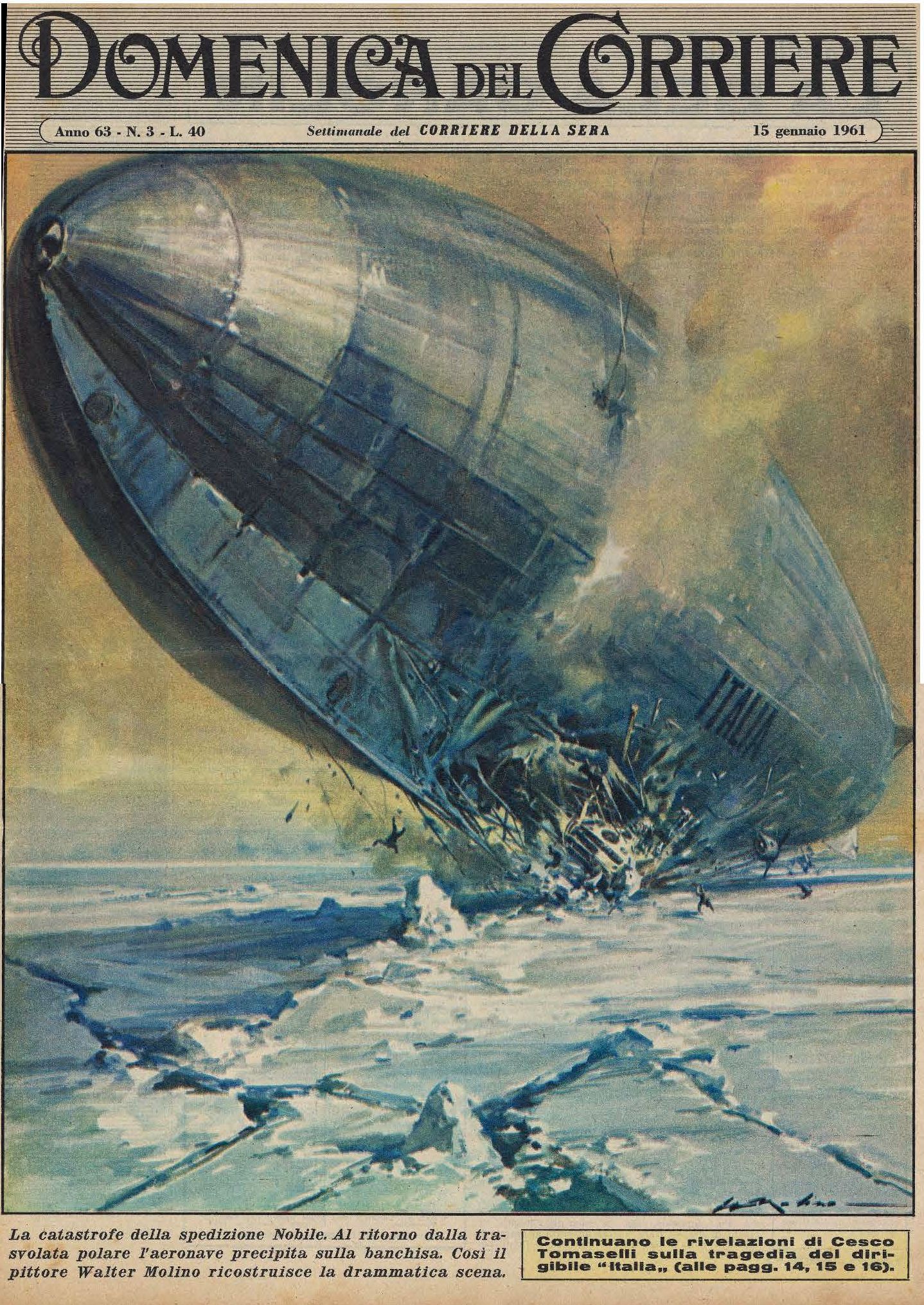

“We are heavy," the crewman shouted as the giant airship dropped through the fog toward the sea ice below. It was as if Thor himself were hurling the Italia out of the sky.

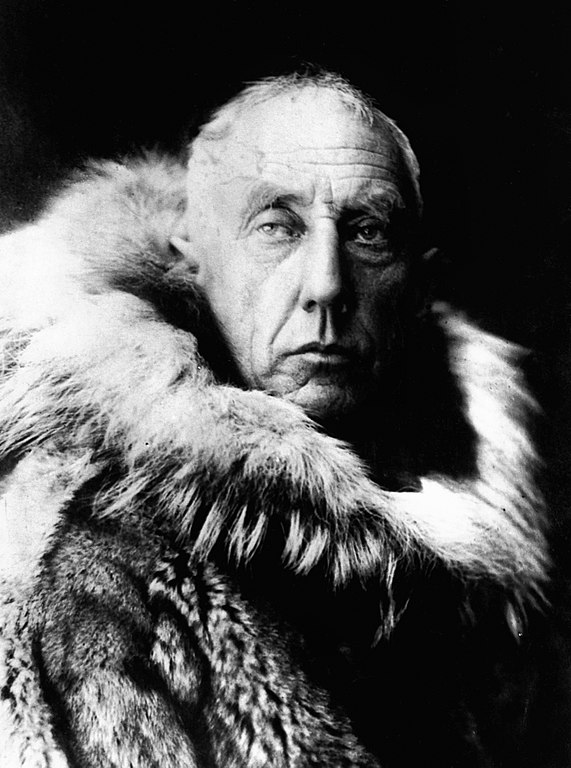

Perhaps the great explorer Roald Amundsen was right, thought General Umberto Nobile, leader of the expedition. The Italians were a “half-tropical breed” who did not belong in the Arctic.

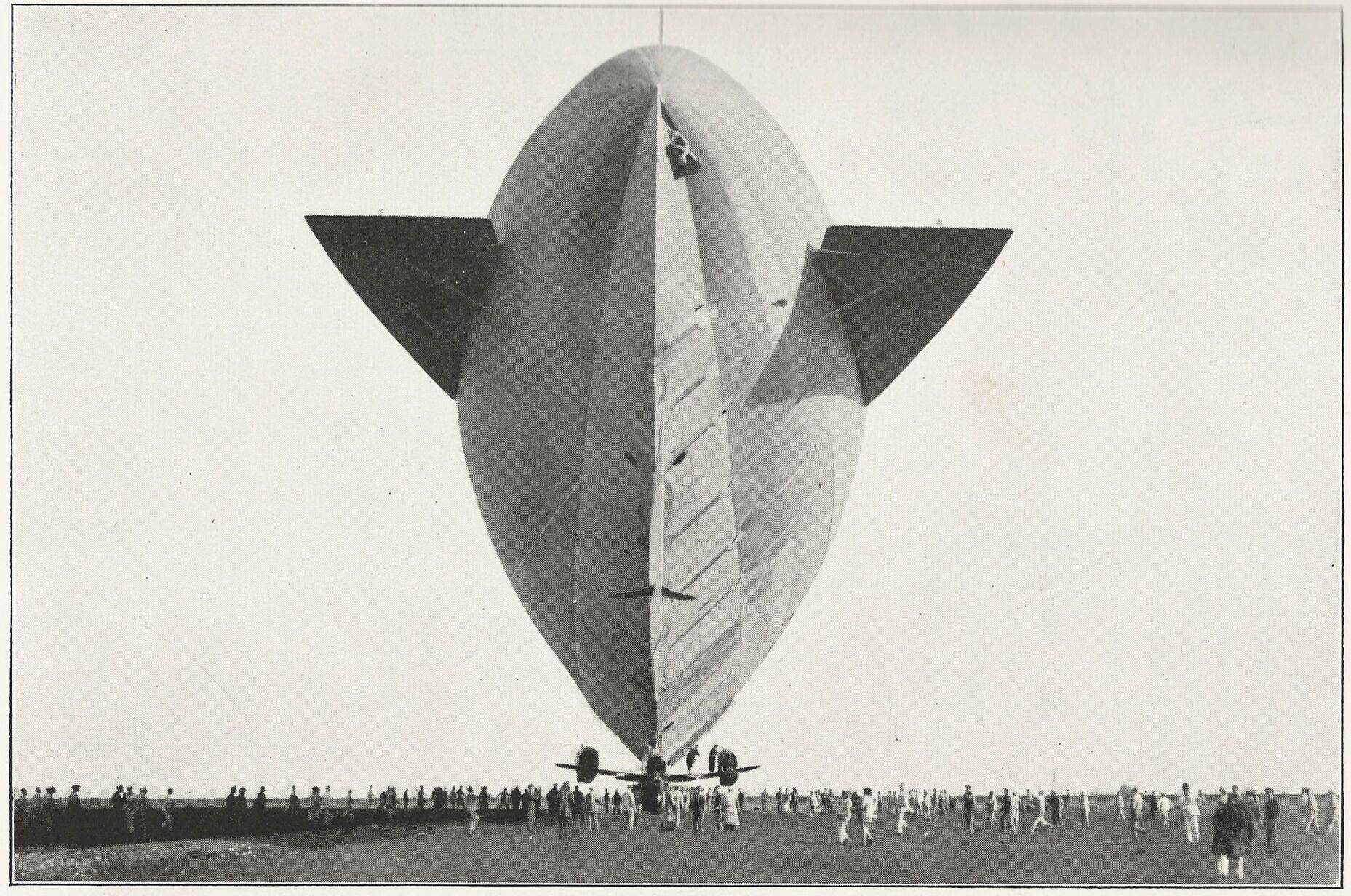

Prodigy, dirigible engineer, aeronaut, Arctic explorer, opponent of Mussolini, maybe even a Soviet spy, and always accompanied by his Fox Terrier, Titina, Nobile twice flew jumbo-jet-size airships—lighter-than-air craft that he himself had designed and built—on the epic journey from Rome to Svalbard to explore the Arctic. The first was the Norge, which Nobile and his crew had successfully flown from Norway to Alaska in 1926 to become the first to overfly the North Pole.

The N-4 Italia was the second of these flying machines. “We are quite aware that our venture is difficult and dangerous…but it is this very difficulty and danger which attracts us,” said General Nobile in a speech to the wealthy and proud citizens of Milan on the eve of his departure in the Italia to Svalbard. “Had it been safe and easy, other people would have already preceded us."

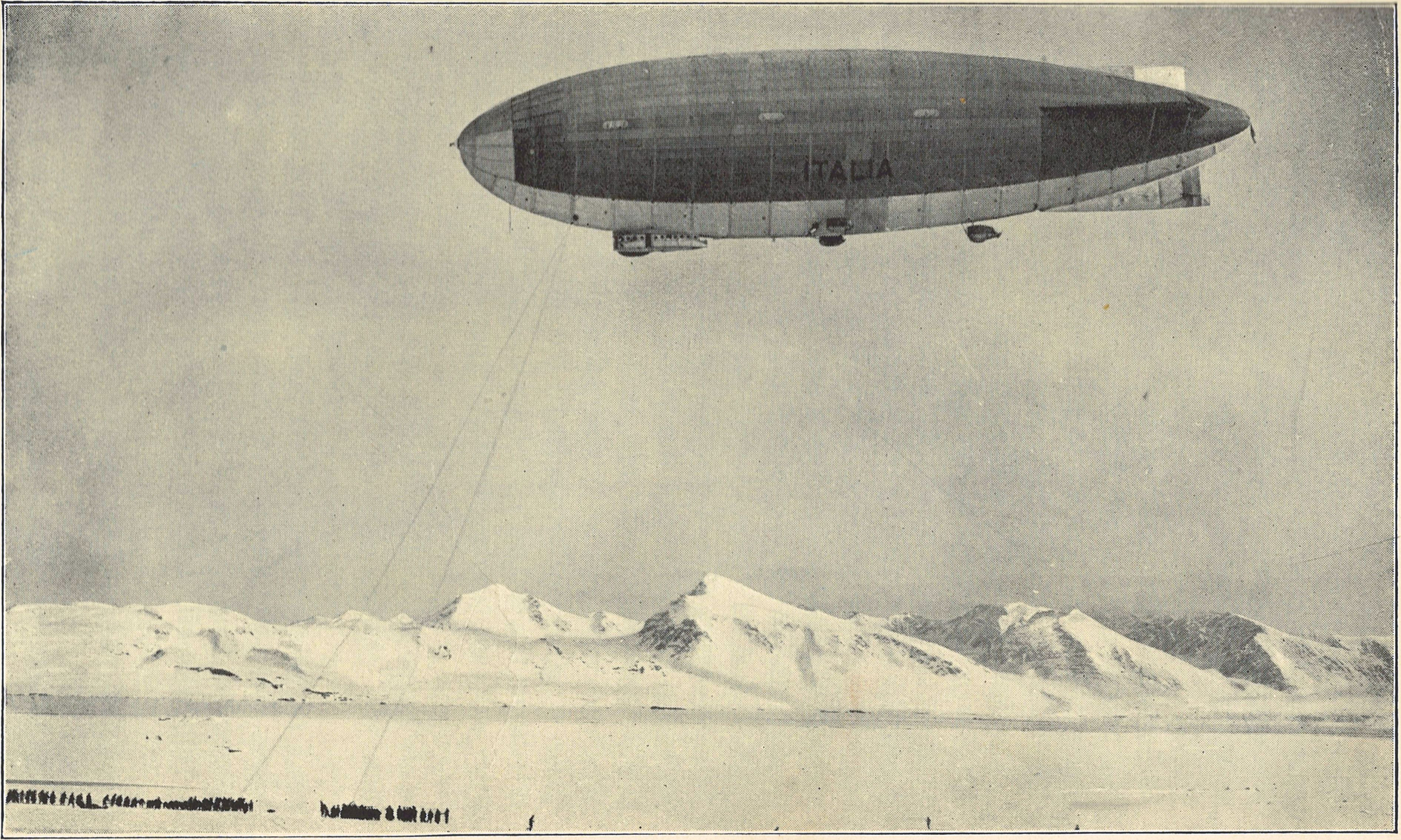

Two months later, General Umberto Nobile in his uniform marched across the snow and ice, and then along the side of the airship Italia as it floated a few feet off the frozen ground of Kings Bay, Svalbard. Its nose was attached to a tall mast that had been plunged into the permafrost two years earlier, and which still stands today. Nobile was forty-eight, but looked younger. This flight was to be the pinnacle of his career, certainly in the eyes of the world’s newspapers and newsreels—and that was, perhaps, all that he needed to be protected from his enemies in Rome.

As Nobile marched, he shouted instructions to his men, who labored in sub-zero temperatures to prepare the dirigible for its flight to the North Pole. Nearby, the coal miners from the Kings Bay Mine stood ready to provide the muscle power when needed. Journalists and photographers recorded the team’s every move. One of them caught the eye of the general and snapped a picture. The last one before he set off.

Behind Nobile and his men stood a strange-looking construction that dominated the bay. It had no roof, but there were two sides made from the type of wooden trestles that you

Beautiful white mountains penned the Italian expedition in on three sides. The glaciers gleamed in the May sunlight. For a moment in the sun, the twenty-two houses of the mining village looked more like holiday cottages. “The Arctic smiles now, but behind the silent hills is death,” a journalist would later write, and he would be proved right.

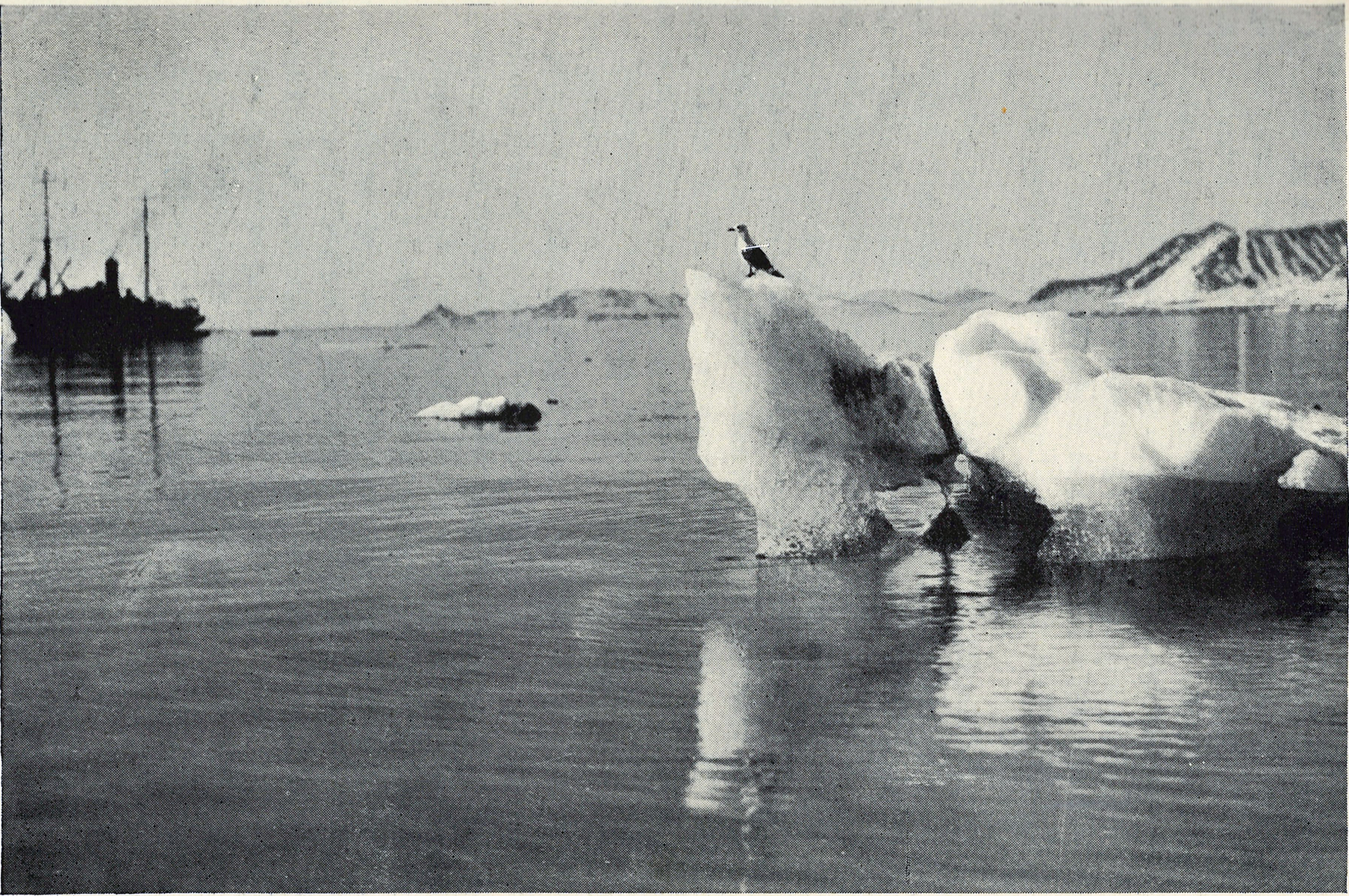

Out in the bay, the sea was filled with great chunks of ice. Beyond stretched the endless ice pack, known as the Arctic desert, a huge empty hole on the map of the world and roughly the size of Canada. Somewhere on the other side was Alaska. Nobile’s mission was to claim any land he found in the name of fascist Italy.

Men on the ice quickly became invisible from the air in this brilliant white landscape. If their primitive flying machines quickly descended and they couldn’t get back up, then there was almost no likelihood that they would be found. Even if someone knew where they were, there would be a good chance that they had strayed beyond the range of their would-be rescuers, particularly if they were the crew of a dirigible like the Italia. These lighter-than-air craft could stay in the air for days at a time and fly much farther than their fixed-wing rivals.

The sea ice that makes up the ice pack was often many feet thick, and then suddenly only half an inch, ready to plunge the unwary—or too-hasty—explorer into the freezing water underneath. Night time might not bring much relief to the explorer, either. The cracking and creaking of the ice kept many a man from sleeping, no matter how exhausted they were, their bodies braced for the moment when they—and their tent—might suddenly be plunged into the freezing water below. Then there was the disorientation. When they woke up, they could be as many as twenty miles from where they had gone to sleep.

To crash out there would in all likelihood mean death, though, surprisingly, this didn’t seem to bother the average adventurer. This was their choice: to be noticed, to be remembered. Glory was what most of them had come here for—and one way or another, they were determined to get it.

Umberto Nobile didn’t look like the typical polar explorer. Born in the shadow of Vesuvius near Naples in southern Italy, he was a descendant of one of the aristocratic families that had

He oozed a quiet confidence—even cockiness. The engineer’s unravaged good looks and smart military uniform were evidence of his years spent with his wife and daughter in Italy, rather than alone on the polar frontiers.

Today, Nobile would be called a prodigy. In 1908, he graduated from the University of Milan with two diplomas: one in mechanical engineering and the other in electrical engineering. He went on to formally study the new science of aeronautics. In 1912, he finished at the top of his class.

By December 1917, Nobile’s star was shining so brightly that he was appointed vice director of Stabilimento Militare di Costruzioni Aeronautiche (SCA). In July 1919, he became the director of the airship factory. He would go on to export airships to countries around the world from his sprawling empire of offices and factories centered on Ciampino, Rome’s second airport.

Two years later, the Roma, which he helped to design, was sold to the United States. The failure of its rudder when flying too fast and low over Norfolk, Virginia in February 1922 led to the Roma crashing into high-voltage power lines and exploding. Thirty-four of the forty-five passengers and crew were killed. The crash was the deadliest such disaster in US aviation history at the time.

The temptation must have been to blame the Italian designers for the crash, yet the fault seemed to lie closer to home. The US military had decided to save money by using flammable hydrogen in the airship, rather than the helium they knew was safer. The Americans had also replaced the Italian engines with more powerful American-built ones, with little thought as to the effects of such a retrofitting.

However, the Italian designers somehow seemed to escape blame, and Nobile’s stock remained high in the United States. The following year, he went to work as a consultant for the Goodyear Airship Corporation in Akron, Ohio—home in modern times of the famous Goodyear Blimp—on the construction of another airship. Announcing the collaboration, Aviation magazine described Nobile as the “foremost authority…in the world.”

In 1923, thirty thousand of Benito Mussolini’s Blackshirts marched on Rome and intimidated Victor Emmanuel III into appointing Mussolini prime minister. Within months, the Fascists had seized control of the machinery of government. Over the next three years, Mussolini dismantled the democratic structures of Italy. In October 1926, he felt secure enough to make himself dictator, giving himself the title “Il Duce.”

Like many educated people in the 1920s, Nobile would admire Mussolini for his ability to get things done. Indeed, his own ambition to explore the North Pole by airship would depend on Mussolini’s ability to do precisely that. Nobile was proud of his nation, had private audiences with the pope, and developed a good relationship with the

Fascist leader Italo Balbo was a different brand of villain from the jealous rivals Nobile had clashed with before. Balbo was a charismatic, street-fighting, cigar-chomping fascist leader. His “chestnut goatee, winning smile, and love of uniforms covered in gold braid and medals” may have made him a bit of a joke to some, but they disguised his ruthlessness and violent behavior. It was said that even Mussolini was scared of him.

Balbo wanted to rebuild the Italian air force around his ego and with two wings—and Colonel Umberto Nobile, his reputation and his airships, were in his way. So, when Balbo publicly declared, “There is no room for prima donnas in the Italian Air Force”— it seemed to Nobile like that was aimed at only one man, himself.

Visitors to Nobile’s factory noted that there was a marked absence of posters of Mussolini on its walls. Egged on by Balbo, it wasn’t long before Nobile’s enemies spread rumors that he was a socialist whose factory was filled with “red laborers” and that he was even the leader of the anti-Fascist resistance.

However, Nobile was an engineer and airman who lived under Mussolini’s regime, which worshipped aviation, and the men who flew these flying machines were portrayed as supermen.

In 1925, the Norwegian polar explorer, Roald Amundsen, along with the American millionaire and coal magnate Lincoln Ellsworth, had wanted to fly to the North Pole in an airship, and Nobile had the only one in Europe that was suitable for the flight, and for sale.

The Amundsen-Ellsworth Expedition joined multiple engineers and explorers in the race to be the first to fly from Norway to the North Pole, across the shaded area on the map labeled “unexplored,” and on to Alaska, in what Polar Science Monthly called “the most sensational sporting event in human history.” The New York Times described it as “a massed attack on the Polar regions.”

If Amundsen thought he was only buying an airship and hiring a pilot, then he had another thing coming. Whether the Norwegian liked it or not, Nobile had the trump card in his hand — the airship — and the Italian rather liked the sound of the Amundsen-Ellsworth-Nobile Expedition. But a careful look reveals something else lurking behind Nobile’s apparent confidence: fear.

It is easy to imagine that, on the jotting paper on Nobile’s desk, one name was written down and underlined: Italo Balbo.

Amundsen and his men were willing to take a gamble on the flight being a success. Their ethos was simply: “One set off — and hoped to come back.” If the airship crashed, they were ready to attempt an incredible feat of derring-do to get them out of trouble.

But for Nobile, the flight had to be a success. Any outcome that didn’t see the airship reach Alaska would be a failure for him, for his family, and for Fascist Italy. The guns would not be fired in salute if he had to trudge on foot to safety across the ice.

It was a competition that the Amundsen-Ellsworth-Nobile Expedition won on May 14, when the airship Norge, designed, built, and piloted by the Italian landed in Teller, Alaska. The New York Times headline read “NORGE SAFE IN ALASKA AFTER 71-HOUR FLIGHT,” and devoted three whole pages to the flight.

Two days earlier, the American, Norwegian, and Italian flags were dropped onto the ice at the North Pole. “Ours was the most beautiful,” one of the Italian crew recalled.

Later, Amundsen would bitterly mock the Italians and their flag. It was too big, he told everyone; it was a joke. The Italians could barely even organize themselves to throw the flag out of the cabin window. When they did, the thing was so large that it nearly fouled the ship’s engines and brought the dirigible down.

The tensions between Amundsen and Nobile exploded when the Norwegian realized that the thousands of Americans lining quaysides and packing train stations were not cheering for the elderly explorer who had been a passenger on the flight, but for the brave, good-looking Italian airship captain who had flown the craft: the man they were calling the New Columbus.

An editorial in Aviation magazine claimed: “In the lighter-than-air [field], General Umberto Nobile has given Italy a rightful claim to leadership in the construction of medium-sized dirigibles. The Norge, which flew the Amundsen party over the North Pole, blazed a trail through the air from Europe to Alaska that will in the years to come rank with the first Northwest Passage as a historic event.”

It was a victory that made Nobile even more the target of Italo Balbo in Rome. No wonder, then, that Nobile decided to escape back to the Arctic almost as soon as he had landed in Teller.

When Nobile told Mussolini of his plans, Il Duce warned him: “Perhaps it would be better not to tempt Fate a second time,” but Balbo told Mussolini to “let him go, for he cannot possibly come back to bother us anymore.” Balbo seemed determined to make that prophecy come true when he turned down Nobile’s request for two or three

In May 1928, the weather seemed to be against Nobile. He was facing rising temperatures, which could compromise the airship’s lifting power because of the expanding hydrogen. In addition, the summer fogs made flying especially hazardous. He started to think the unthinkable — of postponing the flights to the fall, when the temperature would drop again — if, that is, Balbo allowed him to.

However, on May 22, a high-pressure system covered Greenland with colder-than-expected air, a blessing since their planned route to the North Pole would take the airship over the massive island. But there was — of course — a caveat. The Tromsø Institute warned that the “favorable situation [was] not likely to last much longer, because the warm currents [would] give rise to the formation of fog.”

It was 4:30 a.m. on May 23, and more than 150 men were holding the guy ropes that kept the giant airship a prisoner, floating just above their heads. The chaplain, Father Franceschi, offered one last prayer. Nobile shouted, “Let’s go!” The ground crew let go of their ropes with a chorused “Hurrah!” The engines roared to life, and the N-4 Italia lifted off, disturbing a flock of gulls that rose screaming into the sky.

The sun was glinting off the envelope as the airship rose majestically over the mountains and headed north. To many of the men, it was a vision of the future of Arctic exploration. “A shimmering silver shape, glinting far above the ice hummocks and dimly seen from below,” one journalist wrote. “How different from those labored tours of old, when sledge parties left their floe-hemmed craft to toil among the ridges in the white glare of the Arctic.”

The weather report had been as good as it was going to get—but how many times since they had left Milan had the men on the Italia heard that? By the afternoon, the thin layer of dense fog that had accompanied them from Kings Bay out toward Greenland started to turn into something more worrying—a wall of fog. The unbroken white-out wrapped the airship, preventing the navigators from taking their bearings in this featureless landscape.

Finally, at 5:30 p.m., the fog cleared enough that they were able to identify Cape Bridgman on the north coast of Greenland, the point at which they would turn and head straight for the North Pole. Fortuitously, a strong wind suddenly picked up and blew them in the direction of the pole.

But the wind was a mixed blessing. While it meant that the flight to the pole could take a very fast twenty

Nobile spread the maps out on the table in the cramped cabin. He had another plan: to just keep cruising beyond the pole, bearing east to land at Mackenzie Bay in northwestern Canada—a route that he knew well, having flown it successfully in the Norge. He had even made sure that the charts for that eventuality were stowed on board. Nobile asked Finn Malmgren, the ship’s Swedish weatherman and one of two non-Italians on the crew, for his advice. “Better to return to Kings Bay,” he responded. “Then we can complete our research program.”

Nobile also wanted to return to Kings Bay. If they headed for Canada, it would all be over because it would be a one-way flight. Without an airship mast or a big-enough hangar, the Italia would suffer the same fate as the Norge. It would have to be deflated the moment it landed.

But still, he hesitated. He didn’t want to put his men and ship through another exhausting battle against headwinds, as they had experienced on the previous flights. Maybe they could fly around the storm to Severnaya Zemlya off the Siberian coast and then back to Kings Bay. “This was truly a venturesome and attractive plan,” he wrote. But Malmgren was “adamant” that the direct flight home was the best option.

Malmgren finally got his way when he convinced Nobile that the winds would die down. “This wind won’t last,” he said confidently. “It’ll drop a few hours after we have left the pole, and then it’ll be succeeded by more favorable winds, from the northwest.”

There was only one problem. Malmgren was wrong.

At 10:00 p.m. along the horizon lay a wall of cloud 3,300 feet (1,000m) high, as if “walls of some gigantic fortress,” Nobile imagined, had formed to defend the North Pole against the aviators. Somehow, they broke through it.

At 12:24 a.m. on May 24, the cry went up: “We are here!” Nobile ordered the engines slowed and the helmsman to circle the pole.

They were now directly over geographical zero. He had done it. He had proved Amundsen wrong. The Italians could conquer the Arctic.

Slowly, the huge airship circled lower and lower, until they could see the tortured, fractured, and jumbled

There was a moment of disappointment when the crew could not land a party on the ice because the wind was too strong for the “sky anchor” to hold the airship steady. Nevertheless, in “religious silence,” the men made ready to complete “the solemn” duty entrusted to them by Pope Pius: at 450 feet (140m), they dropped the Italian flag, the Tricolore, onto the summit of the world, followed by the flag of the city of Milan, and, finally, the cross that the pontiff had presented to them. “And like all crosses,” the pope had said with a sad smile during their last audience, “this one will be heavy to carry.”

With their jobs done, the gramophone player on the airship belted out the martial notes of the Fascist Party hymn, “Giovinezza,” Italy’s unofficial national anthem. With their right arms raised in the fascist salute, the crew sang along heartily under the watchful eyes of a journalist from Mussolini’s own newspaper, while Nobile looked on.

The singing rapidly gave way to the cry of “Viva Nobile” and a toast of eggnog. Nobile had been here before, but this time, it felt very different - almost as if it were the first time.

The Detroit Free Press headline read “NOBILE CRUISES OVER POLE… STARTS BACK…REACHES TOP OF WORLD SECOND TIME.”

At 2.20 am on May 24, the Italia left the North Pole, flying directly to Kings Bay in the face of the very strong winds that Malmgren had convinced Nobile would clear.

Five hours later, the ship was in a battle for its life. The fog was thick and gray. There was no sunlight. The wind whistled through every crack in the canvas-walled cabin. The metal structure of the ship creaked as if in agony. Its engines were roaring just to keep it inching forward. What sounded like bullet shots from the ice breaking off the propellers made the exhausted men hold their breath, the cold cutting through their heavy lambswool clothing. (Nobile was still in his uniform with the wool sweater that he wore over it because it enabled him to move quickly.)

“Each man went about his work in silence,” wrote Nobile. “The vivacity and cheerfulness that had accompanied our outward journey had now disappeared.” Everyone knew that the fuel was running out.

The ship suddenly felt very small. If the men wanted a chance to get any sleep, they had to bed down in the gangway in the keel. There had been too little rest between the long, demanding Arctic flights they had already undertaken.

By 7:30 a.m. on May 25, they should have been able to see the mountains of Svalbard, but they couldn’t. “I was anxiously watching for the northern coast of Svalbard to loom up in front of us,” Nobile recalled, “and instead, every time I looked out of the portal, I saw nothing but the fog and ice.”

It was then that he couldn’t hide his fears anymore. The crew who knew him could see it in the lines on his face. (The radio operator, Biagi, told the ship at Kings Bay: “If I don’t answer, I will have good reason.”)

This was hardly surprising. Nobile hadn’t slept for days. His lack of sleep was on top of three other exhausting flights in quick succession. He needed a rest, but he was trapped by his culture’s, and his own, sense of what good leadership was all about, by his belief that another pilot would not make the quick decisions he needed to make in an emergency, and by the fear that he could empower an ambitious rival. Without a second-in-command, there was no one who had the courage to tell him to get some rest.

His brain was stuck in slow motion just when events were speeding up. Nobile was so tired that he was hallucinating. In the picture that hung on the wall of the cabin, his daughter, Maria, now looked as though she were crying. He had to tell himself that it was just the condensation on the inside of the glass.

At 9:25 a.m., there was a loud bang, and Nobile heard the cry, “The elevator wheel has jammed!” The controls of the helm were locked, pointing the Italia downward, and at an altitude of 750 feet (230m), it was hurtling toward the ice—and destruction.

With the engines roaring, the lives of the sixteen men on the airship hung in the balance. Nobile had been awake for more than seventy-two hours in the noise and cold of the airship, and, by now, his ability to think straight must have been severely limited.

“All engines, stop!” Nobile cried above the roar of the wind. It was the only thing he could do. With the engines off, the wind should slow the descent of the airship and eventually lift it up again on its currents, away from the pack ice.

Then, at 300 feet (90m), the ship started to ascend again—and quickly. Then Nobile, his brain starved of sleep, made a questionable decision: he let the airship continue to rise and, as a precaution, vented off some of the precious hydrogen that they might later desperately need for extra lift. He could have chosen to restart the engines instead to slow the zeppelin's ascent.

At 3,000 feet (900m), “glorious sunlight” flooded the cabin, lifting the spirits of the crew—but not for long. The sun’s rays would quickly start to heat up the hydrogen in the gas cells, and if the airship stayed too long in the sun, it would

Uncharacteristically for Nobile, who was keenly aware of the danger, he decided to keep the Italia in the direct sunlight for thirty minutes. He could now use the sextant to work out their location and could also finish repairs to the damaged control surfaces, but this was another dangerous move.

With the repairs complete, around 9:55 a.m., Nobile ordered the engines started up again, but he hesitated for a moment, letting the N-4 sail on without power, hoping that he would see the peaks of Svalbard. But there was no sign of home. All he could see was the freezing fog.

The captain had no choice but to let the Italia descend again into the cloud. At 1,000 feet (300m), the storm had cleared enough for the men to see the ice pack every now and then. The wind dropped, just as Malmgren had predicted. The airship was making a decent 30 mph. Nobile even started to think about his bed at Kings Bay.

But the gods were just toying with them.

At 10:30 a.m., the tail of the ship had almost imperceptibly begun to drop. The cry went out: “We are heavy!”

The ship was listing to stern and falling at a rate of about two feet (0.5 m) per second. The earlier release of hydrogen may have condemned the dirigible.

Nobile was shocked. He struggled to explain what was happening. The bow was pointing upward, but the ship was falling. It was against the laws of physics.

There was now only one thing he could do. “All engines. Emergency. Ahead at full!” he shouted. But, according to his instruments, the increase in speed had no effect.

To try to gain altitude quickly, he screamed, “Up elevators!” But that only made things worse. The bow was tilted so high that, if he wasn’t careful, the ship would stall, making its destruction certain.

“She’s still heavy, General!” he was warned, but the situation was obvious to everyone who was awake. Incredibly, some of the crew had been so exhausted that they were still asleep in the tail.

Nobile must have suddenly realized that what had seemed inexplicable could be explained if one of the valves had frozen open and hydrogen was pouring out. He ordered one of his men to “run

There may have been a tear in the envelope of the airship, or ice may have covered the ship as it descended, but the problem was that they were out of time.

“Look! There is the ice pack!” warned Malmgren, his knuckles white as he fought with the steering wheel to turn the airship away from disaster.

Nobile’s eyes were fixed on the variometer. He knew from the rate of descent that they were going to crash. The engines were on full power. The nose of the airship was up at twenty-one degrees and, still, the ice was rushing toward them.

“Stop all engines! Close all ignitions!” he shouted. All they could do was try to prevent the spark plugs in the engine from igniting all the hydrogen in the huge envelope above them if they crashed. The danger that the airship would go up like a Roman candle on impact had haunted all dirigiblists.

“The elevators have lost all response! The wheel is dead!” shouted Filippo Zappi, one of the navigators with significant experience on airships.

Nobile ordered the sky anchor deployed to slow their landing. It had worked at Teller with the Norge, and it should work here. But it didn’t; the cabin was at such an angle that the men couldn’t reach the hatch to deploy it.

There were 100 feet (30m) to go, and they were clearly going to hit the ice too fast—ice that was jagged, not smooth, as it had looked from higher up. There wasn’t even a layer of snow to cushion the impact. And they were going to hit tail-first.

“This is the end,” said Professor František Běhounekto, one of the two scientists on the flight.

“God save us!” were the last words Nobile uttered. The last thing he heard was the snap of his leg bone. His last thought: “It’s all over now!”

It was 10:33 a.m. on May 25.

Today, Dronningen Restaurant can be found on the shore of Oslofjord, as it has been for a hundred years. The white sails of the yachts are still seen out on the water. The only significant difference in the surroundings today is the modernist design of the current incarnation of the restaurant.

In 1928, the Dronningen was housed in a traditional, slatted, wooden, two-story clubhouse with a veranda and a lookout perched on its roof. Its diners were a favorite subject for the brushes of local artists.

At the restaurant

The men were looking forward to their rich meal of broth with beef marrow, smoked salmon, spinach and scrambled eggs, lamb saddle, cheesecake, and parfait. Barely had they raised their forks to their mouths when a telegram boy rushed in with a message from the paper’s correspondent on Svalbard: the Italia had not returned from the North Pole.

The mood turned dark. What could possibly have happened to the Italia? Could it still be in the air? Where could it have crashed? How would the Italians cope on the ice floe? The celebration of Wilkins and Eielson’s triumph was forgotten because of Nobile’s crash. The same sentiment was felt across Europe.

A few minutes later, one of the waiters rushed up to tell the editor of the Aftenposten that the defense minister wanted to speak with him. The editor returned with the news that the explorers needed to go straight to the ministry to plan a mission to look for Umberto Nobile and the crew of the Italia.

The room went quiet. Everyone looked at Amundsen.

There wasn’t a single diner in the room who didn’t remember the bitter quarrel between him and Nobile.

The great explorer’s reply was simple: “Tell them at once that I am ready.”

Where the Italia had hit the ice pack at 10:33 a.m. on May 25 looked like the crash site of any other aircraft, but with one big difference: the airship had survived.

It was only the control cabin under the airship and the stern engine that had smashed into the snow and ice. The rest of the airship was still—more or less—intact, and the huge envelope of the airship still filled the sky above the crash site; on its side, ITALIA was visible in big black capitals.

Free of human control, the airship slowly rose skyward into the bank of fog like the balloon it had now become, its prow pointing up as if it were taking off again, which in a way it was. Two of the three engines were still in place, though useless.

The

The survivors found one of the mechanics in the wreckage like he was bending over to retie his shoelace. When he didn’t respond, they shook him slightly. He toppled forward and rolled faceup. His face was blackened, crushed by impact. He was dead.

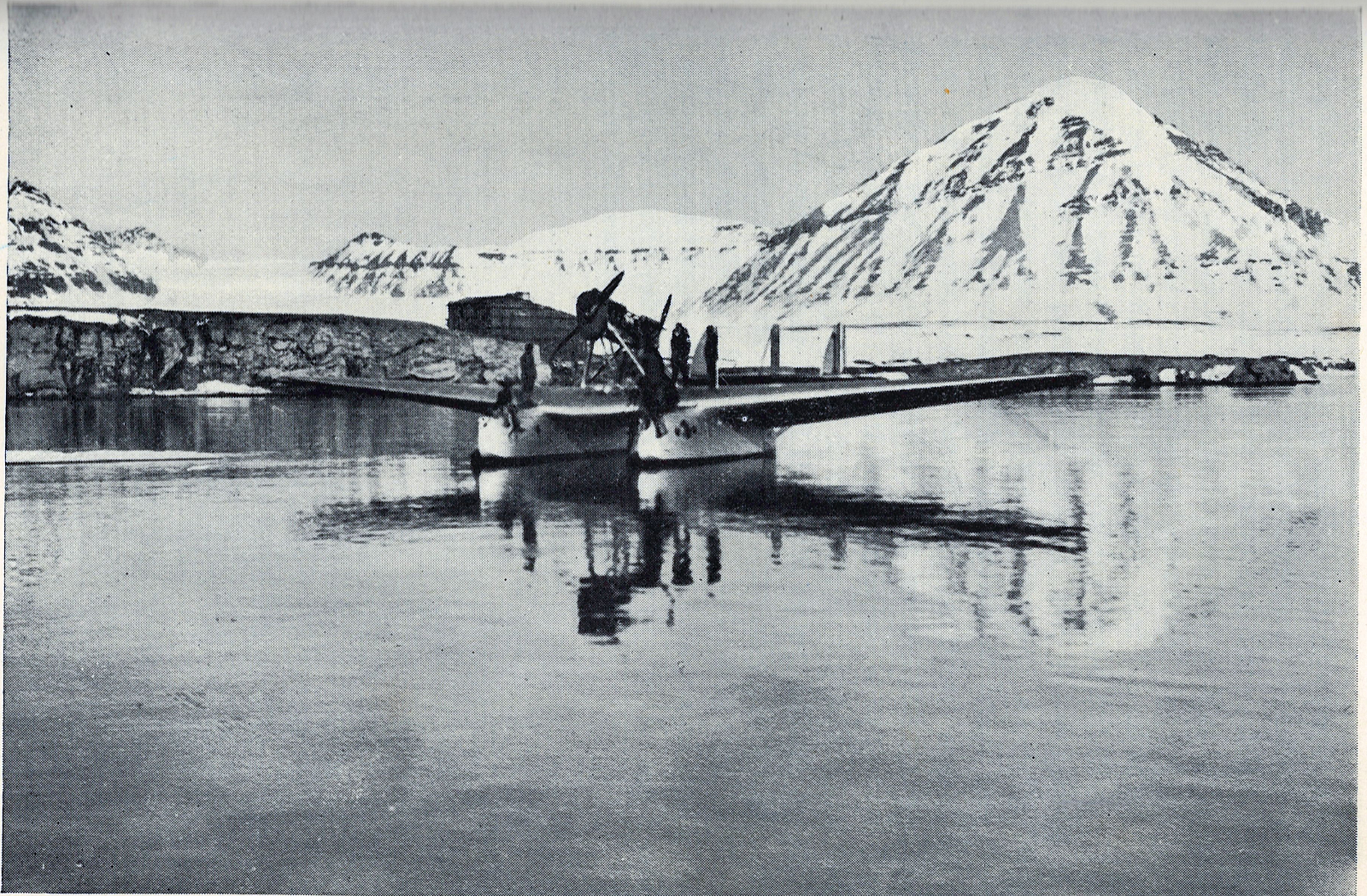

At 4:00 p.m. on June 17, Roald Amundsen’s flying boat taxied across the water at Tromsø. As it raced across the still, calm water of the harbor, it was clear it was struggling to take off. But at last, the plane ascended.

The plane carrying Amundsen and five crew was last seen by fishermen two hours later, out at sea, about forty miles from land, flying into a huge fog bank. It was never seen again.

Six days later, just after 11 p.m. on June 23, a small Swedish plane managed to land on the floating sea ice next to the survivors. The leader of the expedition, the badly injured General Umberto Nobile, was persuaded to break the law of the sea to become the first survivor to be rescued, along with Titina, his Fox Terrier. If Nobile had known how his enemies would use this decision against him, he might have taken a stronger stance against leaving his men behind.

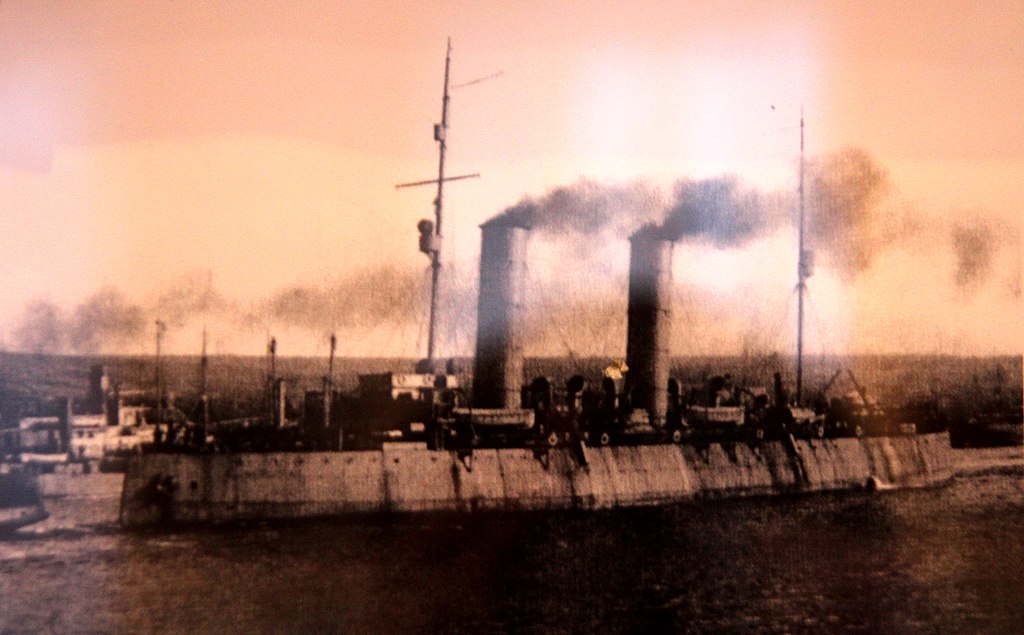

The rest of the survivors, bar one man, were rescued by the Soviet ice breaker Krassin three weeks later. Of Finn Malmgren, there was no sign. His fate, best not to contemplate. Time magazine asked: “Was that Swede really eaten by those Italians?”

Tragically, three more aviators who had joined in the search for Nobile and his men died flying home.

Nobile and the seven other survivors return to face Mussolini. The graves of the 14 dead dirigiblists and their rescuers who died in the Arctic have never been found. Some people hope that the melting ice gaps will eventually reveal their location.