Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2022 | Volume 67, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2022 | Volume 67, Issue 1

Editor's Note: Bruce Watson is a Contributing Editor of American Heritage and has authored several critically-acclaimed books. He writes a history blog at The Attic.

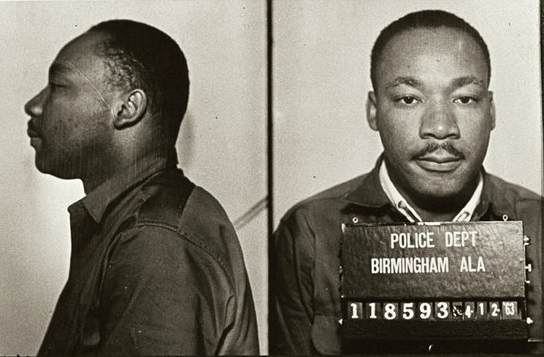

BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA — APRIL 1963 — The cell has no mattress, no sheets. The prisoner sits on a bed of metal slats, scribbling in the margins of a newspaper. The letter is addressed to eight white clergymen, but it should be cc’ed: America.

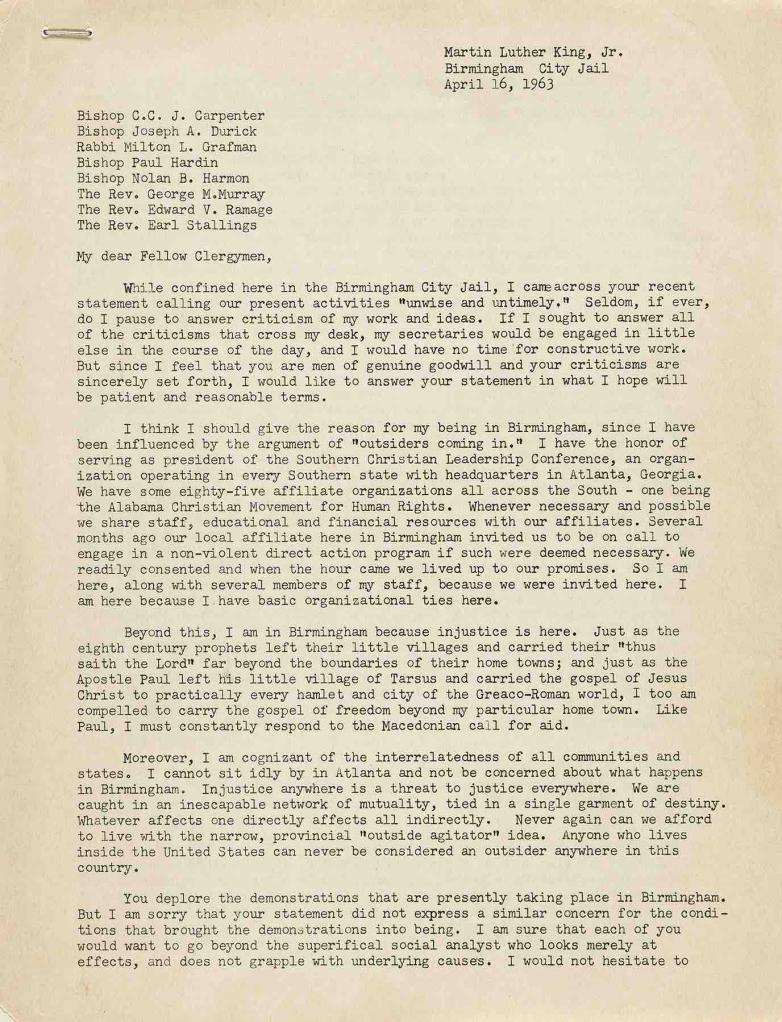

“While confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling our present activities 'unwise and untimely.’ Seldom, if ever, do I pause to answer criticism of my work. . .”

The March on Washington is not yet a dream. The Civil Rights movement has sparked a vicious backlash. Blacks losing faith in non-violence are turning to Malcolm X. Whites are urging patience. The White House considers civil rights a nuisance. But, that spring, Martin Luther King comes to Birmingham.

“If you come to Birmingham,” the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth writes, “you will not only gain prestige, but really shake the country.”

Birmingham: 60 percent white, 40 percent black. No black cops, firefighters, sales clerks, bus drivers. . . Black unemployment doubles white. Just ten percent of blacks can vote. Bombs have destroyed homes and churches, earning the city the nickname Bombingham.

“I am in Birmingham because injustice is here,” King writes in his cell. “I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Arriving in Birmingham, King helps revive a boycott. But “Bull” Connor, the city’s safety commissioner and most blatant bigot, gets a court injunction banning “parading, demonstrating, boycotting, trespassing and picketing.” King has obeyed injunctions elsewhere and seen protests wither. No more. The marches, the boycott continue.

But King soon considers leaving Birmingham to raise funds. What good would he do in jail? “I had never seen Martin so troubled,” a friend writes. King finally decides to stay, to march, to speak, and on April 12, Good Friday, he is arrested.

Back in Atlanta, Coretta has just given birth. And now her husband is behind bars in the South’s most savage city. All weekend, she hears no word. Then, on Monday, a call comes from the White House, informing Loretta that her husband will phone soon. He does, but knowing the phone is tapped, Martin is terse, quiet. That afternoon, a lawyer enters his cell and leaves some newspapers.

The press is bad. TIME denounces the “poorly timed protest.” The Washington Post calls the campaign “of doubtful utility.” But what sets King to writing is the Birmingham News.

“White Clergymen Urge Local Negroes to Withdraw from