Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2022 | Volume 67, Issue 1

Authors: Bob Batchelor

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2022 | Volume 67, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Bob Batchelor is a cultural historian who has written or edited more than two dozen books on popular culture and American literature, including The Bourbon King: The Life and Time of George Remus, Prohibition’s Evil Genius, from which he adapted this essay. Batchelor lives in the Queen City of Cincinnati, Ohio, where Remus centered his bootlegging operation.

“Lock me up. I’ve just shot my wife.”

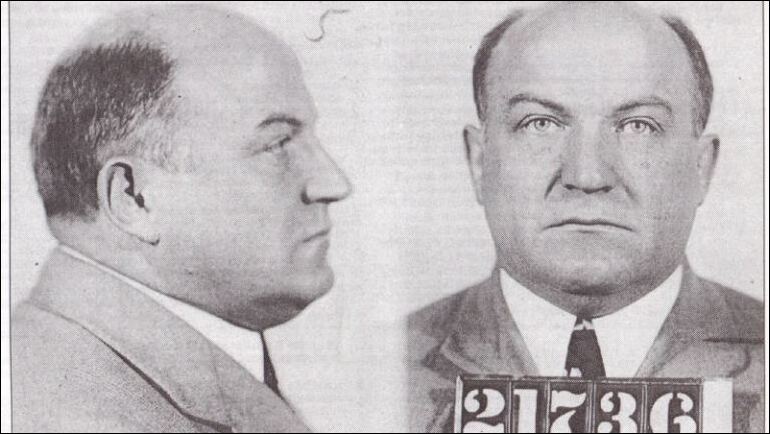

Emmet Kirgan, Cincinnati’s chief of detectives, looked at the man in disbelief. George Remus bounced back and forth in front of the desk, then sank into a chair and surrendered. At the time rich, famous, powerful, and feared, he was widely hailed as “King of the Bootleggers,” and Kirgan recognized him right away. Frank McNeal, another Cincinnati police officer in the room, stopped for a moment, unsure how to proceed. Kirgan stood quickly, grasping what Remus had admitted. Murderers usually had to be caught…

Earlier that day, George felt the blood slick on his hand and looked down in horror. His white silk shirt — crisp and unsoiled only several minutes before — was now awash in red. The pearl-handled pistol heavy in his grip, Remus glanced up, turning toward the street. He heard the women’s screams and the cries of children who had been playing nearby. He searched for an escape, his eyes darting left and right in the morning sunlight that washed over Eden Park.

Emerging from the woods minutes later, Remus surfaced on Gilbert Avenue. A local Studebaker dealer named William Hulvershorn spotted him. He pulled over, offering a lift. Swinging open the dark green coupe door, Remus poked his head inside and then took a seat next to the man, thanking him profusely. The stranger spoke in bursts with a German accent quite strong at times.

“Take me to the central station,” he repetitively muttered between flurries of conversation.

The woman whom Remus left bleeding in the park was his own wife, Imogene, and the end of their relationship in this grisly shooting would become a defining moment in the life and legacy of a man whom the Chicago Tribune described as the “bourbon king” of America. Even after his death in the 1950s, the public would continue to puzzle over the event — and particularly over the high-profile defense case that followed it, during which Remus claimed that he had been temporarily insane when he shot Imogene.

Was this the criminal mastermind of the illegal whiskey trade, or the wife-murderer who got off on a technicality?

See also “Said Chicago’s Al Capone: ‘I Give The Public What The Public Wants…’”

by John G. Mitchell

Today, many Americans look back on Prohibition and fail to see it for the brutal, violence-filled era it was.

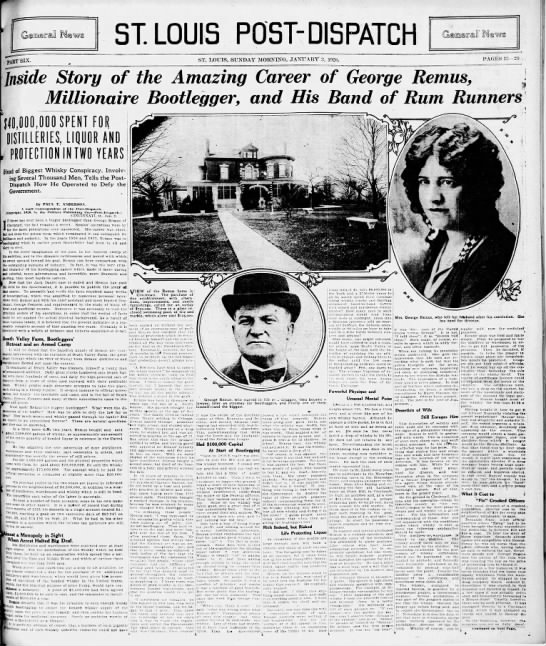

Remus has held his own place in this history of glorified gangsterdom. For decades, he has occupied center stage in one of America’s great literary mysteries, with many wondering if he served as the model for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s fictional bootlegging main character in The Great Gatsby. Remus gained new wave of notoriety he became a central figure in the Ken Burns documentary Prohibition in 2011 and he made fictional appearances in the television series Boardwalk Empire, which focused on Prohibition-era corruption in Atlantic City and the real-life criminal activities of Enoch “Nucky” Johnson.

The attention has been justified. During his time, Remus was one of the most recognizable figures of the Prohibition era, a German immigrant-turned-lawyer who rose from poverty to build one of the largest bootlegging operations in the country. At the height of his power, Remus’s personal wealth would have ranged between $307 and $384 million in relative income today. This is an enormous sum for an operation that held sway for just two and a half years. And if he were able to achieve his most audacious plan — consolidating his various distilleries into one large, legal corporation — his personal fortune would have reached even greater amounts.

Struggle was a way of life for George since he was young. His parents Marie Louise and Carl Franz Remus had emigrated from Friedeberg, a walled city in the Electorate of Brandenburg that became part of Prussia in 1701. While some of their children died young, two daughters lived: Elizabeth and Martha in the 1870s, and their oldest son, George, on November 13, 1876. Over the ensuing decades, George would play fast and loose with his birth year, usually listing it somewhere between 1874 and 1879. The date changed to fit circumstances at the time.

Frank and Marie did not have an easy life in West Prussia, despite her family’s middle-class status, but the situation worsened for the Remus family when they reached America. They arrived aboard the passenger ship Fitlington in New York City in 1882, but unlike millions of immigrants didn’t stay there. Instead, they moved

But the Remuses’ economic challenges persisted. In the late 1880s and early 1900s, leaders in the push for Prohibition attacked casual drinking by German immigrants, a focal point of their culture, especially in the camaraderie and fellowship exhibited at beer gardens. As Frank’s employment woes continued, his drinking increased, as did his time away from home.

George took matters in his own hands, becoming what he called “the main supporter of the family.” He worked as a pharmacist with an uncle, eventually opening his own business and starting a family. He also developed an intense single-mindedness about sports and health, particularly in swimming and water polo competitions, which would become a centerpiece of his life. By his 30s, that combination of smarts, confidence, and hard work enabled Remus to prosper in a new career: law. By 1915, George had helped build his practice into a thriving firm, not only defending high-profile criminals, but also mixing with some of the nation’s finest legal minds.

As a crusading attorney, Remus grew in popularity and became well known as he threw sound bites at newspapermen like machine-gun fire. Not radiant like some barristers who could twirl a jury in their fingers, or brilliant, like Clarence Darrow, the attorney and human rights activist that everyone in Chicago admired, George had a different quality that drew people to him. One aspect was “good copy,” which the newshounds craved. And, observers had dubbed him “the man about town with the moonlight smile.” He wasn’t magnetic like a silent film star, but he had charisma.

But the professional successes masked the fact that things had come to a head at home. After fifteen years of marriage, his wife, Lillian, filed divorce proceedings on March 6, 1915, publicly charging George with “cruelty.” Privately, she told friends that Remus had repeatedly beaten her, striking her with his fists and violently pinching her, in addition to unloading extensive verbal abuse. Lillian also suspected that her husband was with other women on his many nights away.

In fact, George had fallen hard for Augusta Imogene Brown Holmes, a lonely housewife from Evanston, Illinois who wanted to find a way out of a long marriage that she considered a dead end. Beautiful, young, and as eager for wealth and fame as he had become, Imogene brought

Meanwhile, at his practice, Remus’s work changed as Prohibition took hold. Chicago, like all big cities it seemed, had turned to illegal booze with gusto, as if regular law-abiding people enjoyed the walk on the other side of the law. When federal agents and police officers in Illinois began piling up liquor-related arrests, Remus took on case after case of bootleggers pinched trying to quench the Windy City’s insatiable thirst.

The steady stream of liquor cases and the litany of foul-mouthed, nearly illiterate criminals forced George to consider what was happening as a result of Prohibition. Few of the criminals were educated. Most had been poor prior to Prohibition, from working-class backgrounds or fresh off the farm. George knew this was why they had been caught. Many weren’t smart enough to avoid capture. Their methods were shoddy. The bootleggers he defended had taken unnecessary risks with no plans for contingencies.

Remus had built a small fortune and lived well in Chicago, but his work with bootlegger after bootlegger almost compelled him to consider a new life. If these simpletons could make untold money selling illegal liquor, then perhaps he could bring in millions using his intelligence and grasp of the legal codes related to the new amendment. Prohibition had already created untold consequences. Legislators understood that there were potential loopholes in the law when they passed it — they just didn’t think criminals would be so quick to exploit its flaws.

Then George had an epiphany. His plan would be extreme, but the potential payoff would be staggering. Maybe he and Imogene might like living in the heart of bourbon country. Cincinnati, he thought, the thriving industrial and commercial hub founded on the banks of the mighty Ohio River.

“Big money,” Remus said flatly when asked why he turned to bootlegging. But he also wanted more. “I didn’t care anything about money,” he once bragged, “I went into it mostly for thrill and excitement.”

George knew that within 300 miles of Cincinnati about 80 percent of all bourbon in America was manufactured and stored. Gaining access to this liquor would create the heart of Remus’s bootlegging network. Experts also considered bourbon from Kentucky the best in the world, its taste enhanced by

While the Queen City gave Remus access to the vaunted Kentucky bourbon industry, the location also provided less competition than other parts of the country. With competitors eager to service the large cities, Remus would not have the Midwest to himself. However, operating at a distance from New York and Chicago enabled him to supply the chieftains in those ever-thirsty markets without being viewed as a threat that had to be eliminated.

Another significant asset of Cincinnati was its strong German community. The thriving Over-the-Rhine neighborhood contained a countless number of saloons and nightspots prior to Prohibition that stayed open around the clock and provided a rousing nightlife. While most of its many breweries had closed—at least a dozen operating before manufacturing beer became illegal — German heritage still flourished. An intricate network of tunnels for transporting lager ran under OTR and enabled speakeasies to thrive. About 560 neighborhood saloons stayed open after Prohibition, though many were forced to serve refreshment within the gray area of what was legally defined as an “alcoholic beverage,” ultimately selling near beer or soda as a means of survival.

By the 20s, Remus had launched a nationwide network that reached from the shores of the Pacific Ocean to the tip of the Atlantic Coast on ever-drunken Long Island. Remus didn’t anticipate a limit to his growing empire, just a sea of thirsty citizens eager to circumvent the despised Prohibition legislation. His operation outgrew the local Cincinnati, Covington, and Indiana pharmacies that seemed the most logical way to get booze into the hands of eager patrons.

George sent the majority of the alcohol to the large population centers in New York and Chicago. This is where demand surged, insatiable. His underworld contacts in those cities were behind the endless speakeasies and gin joints that seemed to pop up on every street corner. Remus also had to serve the local market. He ensured that a vast web of influential public officials, politicians, and cops had enough whiskey to grease his path.

And yet, despite his skill in building the bourbon empire, Remus proved naive in assessing how his enemies would conspire against him. He did not realize that the more distilleries and whiskey warehouses he purchased, the more he threatened other illegal operators with grand desires. The sheer size and magnitude of Remus’s bourbon kingdom made its continued existence a menace – including in the eyes of the federal government.

In 1921, Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty

Remus would spend the next several years in and out of prison, fighting a slew of criminal charges in connection to his illegal whiskey trade. It was during his stints behind bars that his relationship with his wife began to deteriorate, and Imogene began conspiring against him. Through power of attorney, she took control of his whiskey certificates – the government certified licenses that allowed operations to legally distribute alcohol through local doctors and pharmacies – as well as many other aspects of his bootleg enterprise. And she began an affair with Willebrandt’s star agent, Franklin L. Dodge, Jr.

Discovering the extent of their affair upon his release from prison, Remus was angered to find that Dodge and Imogene had lived in his home while he had rotted away in jail. More importantly for his immediate future, he also found that Imogene and Franklin had cleaned out or destroyed all of his personal and financial records. Without the necessary documents, including stock certificates and records of money owed to him, the bourbon king had no means of authenticating ownership of the remaining pieces of his crumbling empire.

George had just returned to Cincinnati as a free man five months earlier, following his year-and-a-half stint in the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary and another year in a rural Ohio prison. Husband and wife had spent the time hurling lawsuit after lawsuit at one another. Remus accused Imogene of adultery. His legal team attempted to have Imogene’s divorce case nullified or overturned, yet his unruliness caused his lawyers to drop him as a client. He had exploded in bouts of yelling and erratic behavior when they discussed the details of the lawsuit.

Then, on October 6, 1927, a dazzling Indian summer day in Cinncinati’s well-heeled Eden Park neighborhood, Remus’ frustrations exploded. He sat outside the Alms Hotel, an ornate, new building where he knew Imogene and her daughter, Ruth, had been staying. George had sent a messenger into the hotel in an attempt to contact his wife. He wanted to set up a meeting with her to hash out their property disputes before a judge would need to settle the matter. Both husband and wife thought the other was hiding assets.

And then George saw his estranged wife walk out of the building with his adopted daughter, not Dodge. They entered a cab. Remus’ anger grew, he recalled later, particularly after he “saw her laughing and joking as she left.”

The bootleg baron lurched forward in his

His driver gunned the big engine, shooting southward on Victory Parkway in hot pursuit. He kept up the wild pace, weaving through the morning commuters as the road narrowed to become Eden Park Drive. The roadway severed Eden Park, Cincinnati’s ornate urban green space on the northeast border between downtown and the growing suburbs.

“There’s Remus,” Imogene shouted when she recognized the commotion. Ruth, nearly frozen with fear, blurted out to Stevens, “Go ahead!” Both cars rushed through more traffic. Remus’ driver accelerated, surging out in front of the other vehicle several hundred yards later. Remus leaned forward, grabbing the wheel and wrenching it from his driver’s hands. Turning fast, he forced the smaller vehicle up onto the berm, both coming to a screeching halt.

Shrieks of panic cut through the air when the sounds of roaring engines, squealing brakes, and twisted metal shattered the scene. A line of cars ground to a standstill, some blasting into the ones that stopped short just ahead of them. For morning commuters, the day had just turned into a nightmare.

Both women moved toward the car door. Ruth tried to get out and run, but her mother grabbed her and pushed her back in. Imogene escaped from the taxi on foot. Remus, already out and moving toward her, chased her a short distance, eventually seizing her right wrist. Imogene could not break free from the powerful grip. She twisted her arm and kicked at her husband. George held tight, screaming obscenities at Imogene and then smashing his fist into her face. Onlookers froze in fear.

Remus wrenched Imogene close to his body, as if they were caught in a timeless photograph of a loving couple on the ballroom dance floor. In the rush of madness, George had drawn a pistol from his coat pocket.

Imogene pleaded, “Oh, don’t hurt me, Daddy, you know I love you! Don’t do it, don’t do it!” She begged for her life. “You degenerate mass of clay, take this…” he yelled, blind with rage.

George pressed the small pistol against his wife’s belly and fired. A single shot blew a hole in Imogene’s abdomen. He gripped her waist tightly and continued shouting. Bystanders watching the horrific scene could not hear what he said, but he raged on. Feeling Imogene go limp, George then dropped her to the ground.

Two hours later, Augusta Imogene Remus died without ever regaining consciousness.

Several miles away, Remus marched into Cincinnati’s District One police headquarters. He had walked away from the murder scene, been mistakenly driven to the downtown train station, and then taken a cab to the police building.

Chief Detective Emmett D. Kirgan brought Remus back to the present, telling him, “You accomplished what you set out to do.” Calmly, with a slight hint of satisfaction, Remus shrugged and said, “She who dances down the primrose path must die on the primrose path. I’m happy. This is the first peace of mind I’ve had in two years.”

Despite what Remus had said earlier to Dunning and Cincinnati detectives, he changed his tune once he stood in front of the judge. In a brief arraignment hearing on October 7, 1927, which lasted only a handful of minutes, Remus pleaded “not guilty” and asked that his case be adjudicated before the grand jury as soon as possible.

George also declared: “Remus will defend himself!”

For the outside world looking in, the theatrics had already begun. George, the master legal tactician, simply had to launch the attack. These fireworks would be followed with repeated volleys directed through the media, just like the old days in Chicago.

“I’m going to put the whole case to a jury on its merits and let my peers decide my fate,” Remus declared. Remus’s friends and allies played a significant role in setting the tone. They hung from the rafters, packing Judge Chester R. Shook’s courtroom to capacity. Instead of being shunned, the bootleg baron took on an air of respected benefactor, as if the congregation were gathered around for a church service or Sunday picnic. All these spectators, George certainly implied, would not give such overwhelming encouragement to a murderer.

At the core of George’s plan was a smear campaign designed to persuade any potential jury that he was the victim of a carefully conceived plot — Imogene and Franklin robbed him of his dignity and fortune. Could he convince readers — and future jurors — that murder could be justified? The cornerstone of Remus’s efforts concentrated on giving newspaper reporters the juicy details they needed to keep him in the headlines.

During the initial days and weeks of planning for the trial that would determine his fate, George’s favorite word became “unbalanced.” The notion perfectly captured the idea he wanted to convey, while also depicting the mood he wanted readers and future jurors to absorb.

George created a legal term — essentially a slogan for his campaign — that rationalized the murder: “transitory maniacal insanity.” Remus later defined it for observers, but he felt that jurors didn’t require precision. “As a result of the emotions that have been reflected in the mind,” he said later, “as a result of the activities, that, impulsively, something takes hold of you and you do an act for which you are sorry after it has been performed.”

To make it clearer, he applied the concept, explaining, “He was irresponsible at the time of the shooting of that pistol, a temporary insanity only at the time of firing of that gun.”

Most significant of all, George would defend himself from the proverbial hangman’s noose. Remus had been an opponent of the death penalty dating back to his attorney days in Chicago. Certainly his close relationship with Clarence Darrow played a role in his thinking. Darrow remained a key figure nationally, particularly after defending Nathan Leopold Jr. and Richard Loeb, the teenage sons of two wealthy Chicago families who had been arrested for the murder of Bobby Franks, a 14-year-old neighborhood boy. Darrow, in a cunning effort to save their lives, had the boys admit their guilt, and then closed the case with a twelve-hour argument that convinced Judge John Caverly to give them life sentences instead of death because they were mentally ill and had no emotional gauge to comprehend what they had done.

Now, three years later, the Remus case — with its question about temporary insanity — kept people on the edge of their seats. Across the country, they eagerly waited for every scrap of information that surfaced. It was almost as if Prohibition and the death penalty were on trial with Remus.

Remus’s plight returned him to folk hero status around Cincinnati, much to the chagrin of polite society. Visitors overwhelmed the Hamilton County Jail. Excited by the stories blanketing the papers, crowds were curious, hoping to catch a glimpse of the famous bootlegger who had murdered his wife. As he prepared for the fight of his life, George had to plead with officers guarding his cell to curb the steady stream of guests. Media only, please.

The interviews and subsequent stories gave Remus free reign to pontificate and spin. Relying on his experience as one of the nation’s top criminal defense attorneys in Chicago and his increased notoriety as the “Bootleg King of the Middle West,” Remus

During the trial proceedings, through witness testimony and depositions, jurors were given a recent-history lesson on Prohibition’s deadly underworld and the forces at play in Remus’s war against Imogene and Franklin. Imagine a juror, an average Cincinnatian, being confronted with it all. And imagine how it may have painted Remus as a man constantly in fear of betrayal and murder since his release from the Atlanta prison in September 1925.

A highly publicized long-distance shouting match with Franklin and Imogene in the press was one thing, but the revelations at the trial shocked the jurors, hundreds of spectators, and the reporters who sent all the salacious details out over the newswires. When accusations turned to allegations involving murder plots and assassinations, the warfare became very real for everyone paying attention to the Remus murder trial….

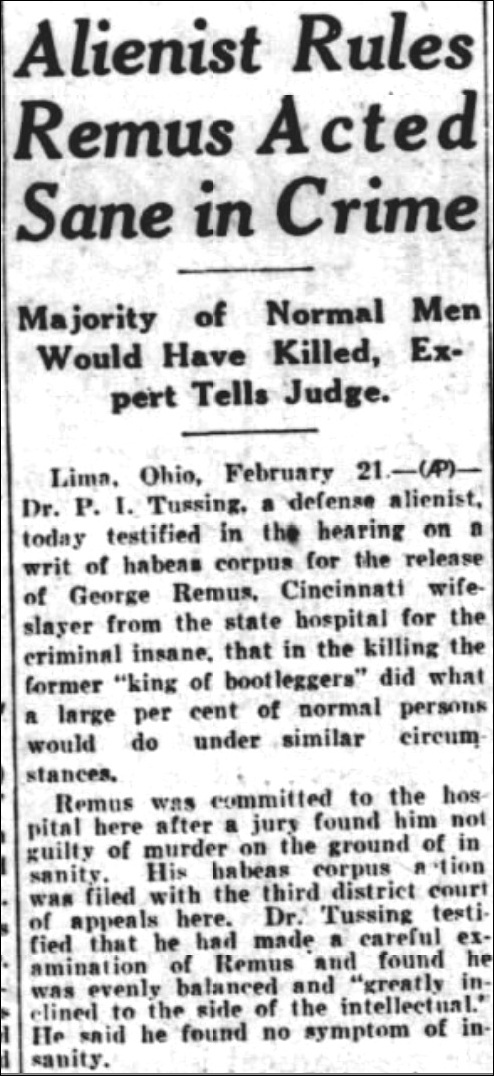

The twelve members of the jury in this highly publicized trial deliberated for just 19 minutes before declaring George Remus innocent of killing his wife Imogene on the sole ground of insanity. If Judge Shook had not intervened, the jury members later affirmed that they would have allowed the defendant to walk away free. Clearly, the jurors felt sorry for George, not his murdered wife: “We all felt Remus had been persecuted enough, hauled through all those jails,” explained one juror.

Remus would not die for murdering Imogene in cold blood, but the state would not give him his liberty either, especially since the prosecution and judge saw the verdict as a travesty of justice. After ordering a probate hearing to determine Remus’ sanity, Judge William Lueders decreed George “insane and a dangerous person to be at large.” George would, in fact, spend his Christmas holiday in prison. But this was a small price to pay considering the alternative.

But the judge’s decision contradicted the findings of the three new alienists he brought into the case to serve in an advisory role, who believed that Remus was then sane and had been when he murdered his wife. A month later, on March 30, the Allen County Court of Appeals issued a 2-to-1 decision to free Remus. On June 19, 1928, after enduring the Lima facility, George was ordered freed by a 4-to-3 decision by the Ohio Supreme Court upholding the earlier determination.

Remus had spent about six months at Lima, all the while using the legal system in an attempt to prove his sanity and win freedom. He served his time counseling other inmates and buying gifts for them. Later, he earned the nickname “Johnny Appleseed of Lima State Hospital” for planting an apple orchard on the grounds, dubbed the “Remus Grove.”

Remus’s not-guilty verdict and his continued incarceration while the courts sorted out his sanity seemed a microcosm of Prohibition America. Enforcement had simply fallen apart. Public outrage, increasing

By 1950, Remus had been ill for the last couple of years after suffering a stroke on August 9 that kept him hospitalized for three months. He convalesced at 1810 Greenup Street in Covington, a small craftsman-style home next door to the house he and Blanche Watson, his longtime personal secretary (and third wife), lived in and owned. What the newspapers failed to mention at the time was that, the day of the stroke, George had been admitted to Bethesda Hospital, the same facility that had attempted to save Imogene after the fatal gut wound nearly twenty-three years earlier.

The Chicago Tribune, which had launched George into the national spotlight in his early years, paid tribute to him when he died on January 20, 1952. Although just about every fact in the obituary was incorrect — including the spelling of “whiskey” — papers around the nation ran similar pieces, calling his career “spectacular” and re-establishing him as the “bootleg king.