Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

| Volume 1, Issue 1

Authors: Steven Waldman

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

| Volume 1, Issue 1

Editor's Note: Steven Waldman is one of our most articulate thinkers on the subject of religion. He was National Editor of US News & World Report and founded the multifaith religion website Beliefnet.com. He has also published several books including Sacred Liberty: America's Long, Bloody, and Ongoing Struggle for Religious Freedom, from which he adapted this essay, and Founding Faith: How Our Founding Fathers Forged a Radical New Approach to Religious Liberty. Waldman currently runs Report for America, a nonprofit dedicated to strengthening our democracy through local journalism.

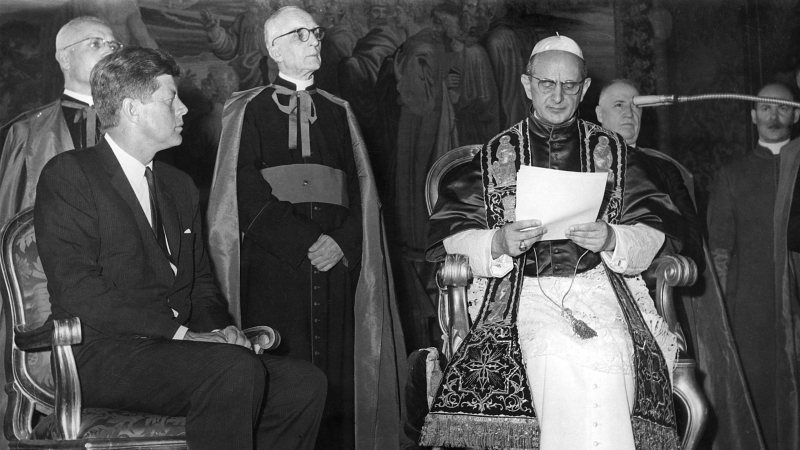

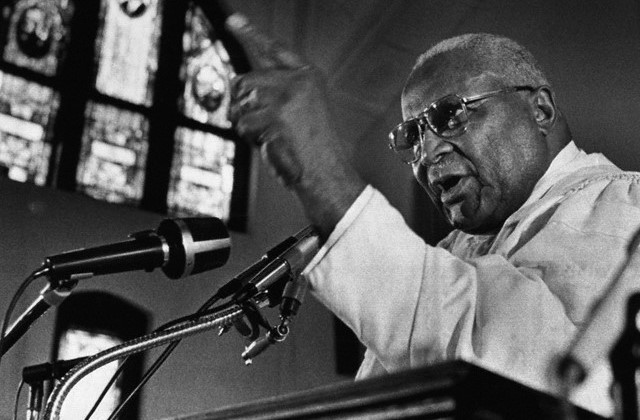

During the 1960 presidential campaign, a group of Protestant ministers in Georgia put their names to an advertisement declaring that they could not vote for John F. Kennedy because he was Catholic. One of the signatories was Dr. Martin Luther King Sr. “Daddy King,” the father of the civil rights leader, was like a lot of traditional Protestants, white and black. He viewed Catholics with suspicion or hostility.

Daddy King changed his attitude in October 1960 after his son was imprisoned for eating at a segregated lunch counter in Atlanta. Martin Jr.’s wife, Coretta, was terrified that he would be killed in jail. While John F. Kennedy, the Democratic Party candidate, had been cautious on civil rights, his advisor, Harris Wofford, convinced him that a simple phone call would make a huge difference.

Kennedy made the call and told Coretta that he was thinking of them and wished them well.

Daddy King was impressed. On the night his son was released from jail, he explained, with jarring candor:

“I had expected to vote against Senator Kennedy because of his religion. But now he can be my president, Catholic or whatever he is. It took courage to call my daughter-in-law at a time like this. He has the moral courage to stand up for what he knows is right. I’ve got all my votes and I’ve got a suitcase and I’m going to take them up there and dump them in his lap.”

The Kennedy campaign quietly distributed a pamphlet known as “the Blue Bomb” because of the color of its paper, in African American communities to publicize the call. Kennedy won 68 percent of the black vote, a seven-point improvement over the previous Democratic nominee.

Shortly before Election Day, Wofford was alone with Kennedy. The future president said, “Did you see what Martin’s father said? He was going to vote against me because I was a Catholic, but since I called his daughter-in-law, he will vote

Anti-Catholic bigotry persisted for most of American history. When the Declaration of Independence was signed, nine of the thirteen colonies barred both Catholics and Jews from office. In the 1830s, Protestant mobs burned convents, sacked churches, and collected the teeth of deceased nuns as souvenirs during anti-Catholic riots in the 1830s—just one of the many spasms of “anti-papism” that roiled America.

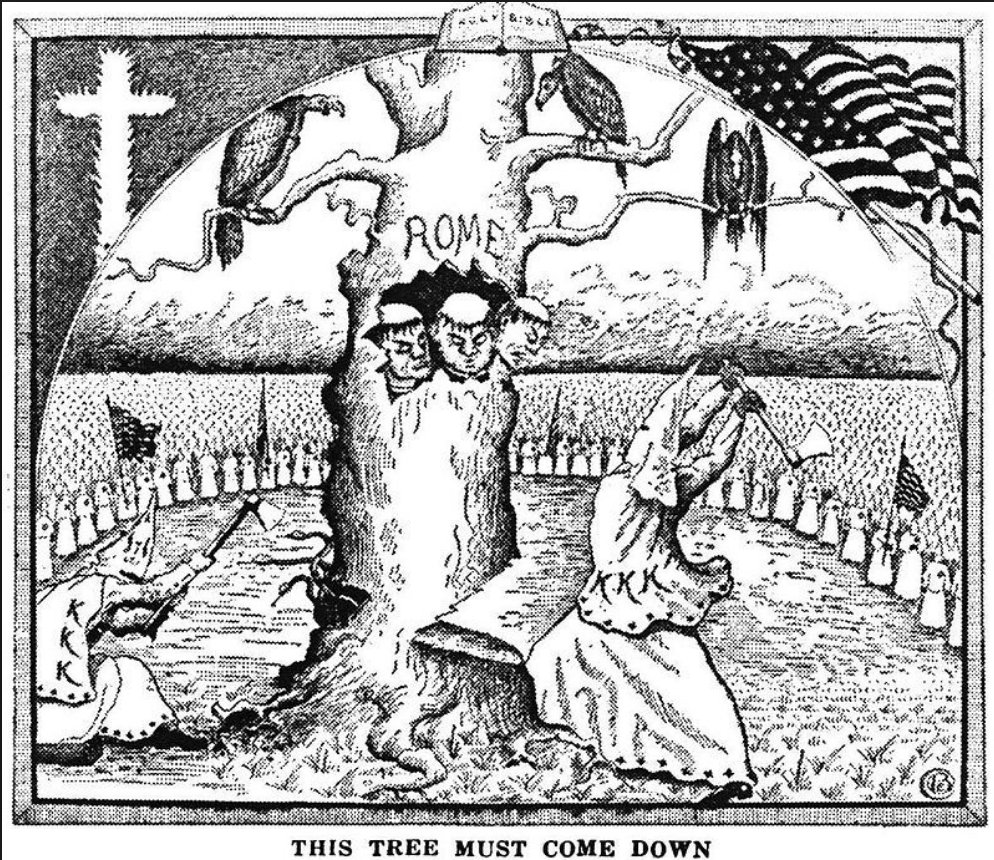

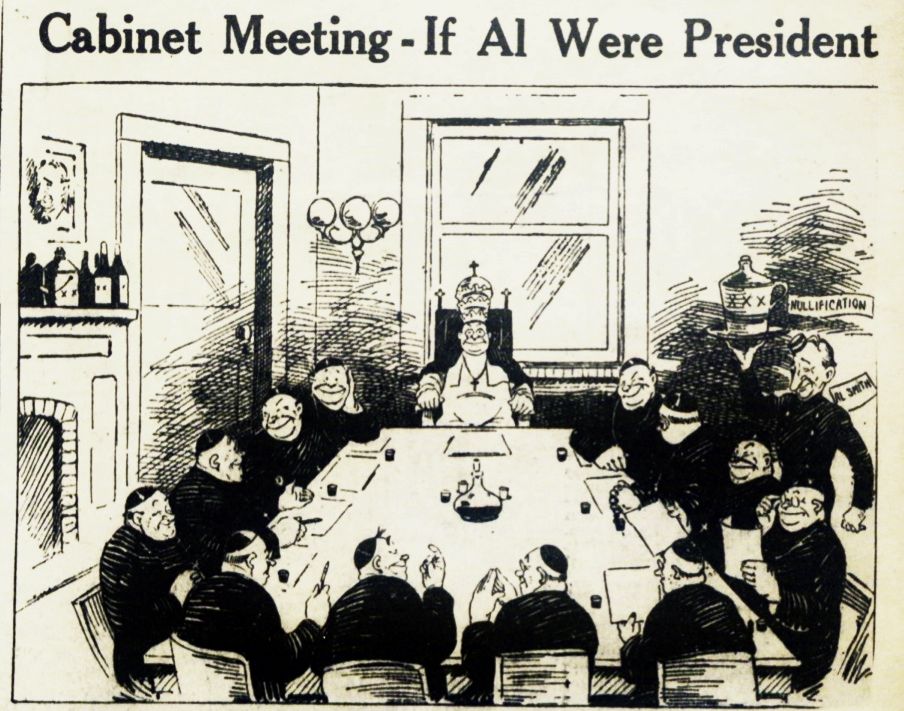

In the 1920s, the rise of the second Ku Klux Klan was driven as much by animus toward Catholics as toward Blacks and Jews. In 1928, Democrats conducted a laboratory experiment in American tolerance by nominating Alfred E. Smith, who embodied every negative stereotype peddled by fearful Protestants—a Catholic, Tammany Hall–connected, anti-Prohibition Irish Italian American. To have one of their own nominated by one of the two major parties was an extraordinary milestone for American Catholics. The four-term governor of New York was a beloved progressive, whose policies laid much of the groundwork for the New Deal. But his candidacy brought a level of religious vitriol not seen since the Jefferson-Adams election of 1800.

Throughout the campaign, Smith was depicted as the pope’s puppet. Klansmen claimed that a photo of the recently completed Holland Tunnel in New York City actually showed a newly built secret pathway from Rome to the United States, through which the pope would arrive and take over the country. Around the country, signs appeared making it clear what the main issue was: “For Hoover and America, or For Smith and Rome. Which?”

In Muncie, Indiana, a twofer conspiracy theory spread: the Catholics had invented a powder that would bleach the skins of black men so they could seduce and marry unsuspecting white women. Other fliers claimed that if Smith were elected, Protestant marriages would be annulled. As Smith arrived in Oklahoma City, he could see the burning crosses of the KKK across the countryside.

At the Democratic convention in Houston, where Smith became the Democratic nominee, several Klansmen dragged a life-size effigy of Smith into the convention hall, slit its throat, and threw fake blood on its chest. At one rally, a KKK official told a crowd of five thousand that they stood ready to block Smith from winning the presidency: “There are 6 million people in the United States who have pledged their lives that no son of the Pope of Rome will ever sit in the Presidential chair.”

Nationally, the Klan sharply divided the Democratic Party. At the 1924 Democratic National Convention in New York City, Klan opponents offered an

In 1927, one thousand white-robed Klansmen joined the regular Memorial Day parade in Queens. The Knights of Columbus, a Catholic group, pulled out of the parade to protest the Klan’s inclusion. Police and Klan members fought, with the police claiming that the Klan had violated a pledge to go hoodless. Klan members subsequently claimed that “Native-born Protestant Americans” were being “assaulted by Roman Catholic police of New York City.” Their propaganda included the “one school” message that proved so popular in other parts of the country. “Liberty and Democracy have been trampled upon when native-born Protestant Americans dare to organize to protect one flag, the American flag; one school, the public school; and one language, the English language.”

One of seven people arrested during the rally was Fred Trump, Donald Trump’s father, according to 1927 news accounts. Some newspaper articles said all of those arrested were Klansmen, but another account said Trump was detained “on a charge of refusing to disperse from a parade when ordered to do so” and that he was “discharged” at the arraignment.

A separate article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle described five of the seven—but not including Trump—as Klan members. Donald Trump denied that any of this even happened.

For most of American history, anti-Catholicism was a central theme of the American experiment. And then, suddenly, at least in terms of the long arc of history, this anti-Catholicism faded. Between roughly 1960 and 1990, the pace at which Catholics were accepted accelerated. Proof of how far we have come was on display in 2016 when the United States Supreme Court began its session by seating six Catholics and three Jews as justices. Men and women who would not have been allowed to hold office in early America would pass judgment on paramount questions of state, including religious liberty. And while it was historic that John F. Kennedy won the presidency in 1960 despite tremendous controversy about his religion, it was in some ways just as remarkable that in 2020 Joe Biden, a practicing Catholic, won the presidency without his religion being an issue at all.

How did this sudden change happen?

We’re accustomed to thinking that religion shapes politics, but during this period, it worked in reverse. The exigencies of electoral coalition building helped pull down walls between religions.

It happened first on the left, as the nomination of a Catholic Democrat, combined with the dynamics of the civil rights and anti-war

This period also saw perhaps the greatest example yet of how American values can sometimes alter the complexion of even ancient religions. A dramatic effort by Catholic leaders in the United States, led by an academic named John Courtney Murray, prodded the Vatican to embrace the American approach to religious liberty. This further eased the integration of Catholics into American society by removing any inconsistency between their position and that of Rome. Religious freedom, it turned out, could become an American export.

Anti-Catholicism in the mid-twentieth century was not limited to fundamentalists. Many liberals viewed the Catholic Church as a powerfully oppressive force. A bestselling anti-Catholic book in 1949 by the civil libertarian Paul B. Blanshard, American Freedom and Catholic Power, criticized state support of Catholic schools, the Church’s censorship of movies and books, and the ban on birth control in Catholic hospitals. He called for a resistance movement” against the “Catholic plan for America” and its “undemocratic system of alien control.” Some liberals also associated the Church, strongly anti-Communist, with the excesses of McCarthyism and anti-Semitism.

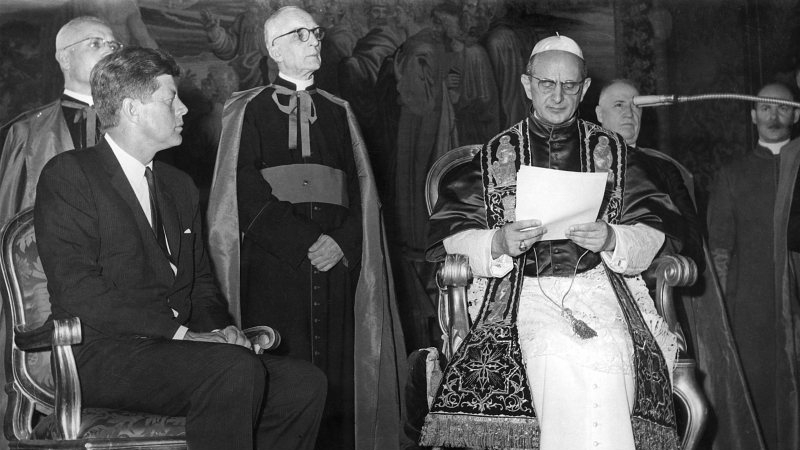

Kennedy’s campaign, just thirty-two years after Al Smith’s drubbing, eroded anti-Catholicism on the left. Like Daddy King, many Democrats who had been suspicious of Catholics found reason to open their minds. Kennedy’s tactical decisions helped. On September 12, 1960, before the Greater Houston Ministerial Association, he laid out a vision that was quintessentially Madisonian but at odds with the traditional approach of the Catholic Church.

The speech reflected a shift for Kennedy, who earlier in his career had backed government support

In a sign of just how much Catholic fortunes had changed, when Kennedy became president in 1961, both the majority leader of the House of Representatives, John W. McCormack, and the Senate majority leader, Mike Mansfield, were also Catholic.

Meanwhile, the civil rights and anti-war movements further strengthened relations between liberal Catholics, Protestants, and Jews. Martin Luther King Jr. reached out to religious leaders around the country to join the march in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 and was thrilled to see that more than nine hundred Catholics, including scores of priests and nuns, answered the call.

The other Catholic breakthrough in the 1960s involved the Vatican itself. Earlier papal encyclicals and pronouncements had criticized the American approach to religious pluralism. Like modern Muslims, Catholics were held accountable for doctrines over which they had minimal control. If anything, American Catholics were in more of a bind: while Islam has no central religious body, Catholics were supposed to follow guidance from Rome.

Remarkably, in the 1960s the American Catholic leadership pushed back, helping to reshape Vatican theology. A prominent Jesuit scholar, John Courtney Murray, had been writing for more than a decade that the Vatican’s approach to religious freedom had become antiquated and that American pluralism offered new possibilities.

Since the Church can’t just change its mind willy-nilly, Murray argued that previous papal proclamations had been appropriate, context-specific reactions to a type of modernism exemplified by the French Revolution, which had perverted the idea of religious freedom to attack the church. But in the United States, Murray argued, “the Church is completely free to be whatever she is.” The Church should still, of course, insist that its spiritual vision was correct, but it should no longer seek government enforcement of those views.

Murray was initially resisted by other Catholic theologians, who argued that “no other form of religion has any right by divine law to exist or to propagate. ... Ours is the only religion that has a right to exist.” Encouraging religious freedom would promote “indifferentism,” the idea that one faith is as good as another.” As one hostile bishop complained, Murray’s approach conferred the same rights to both “truth and error.” For a time, these conservatives successfully silenced Murray. One friend in the Vatican advised him to stay out of trouble by focusing on his poetry.

But in 1962, Pope John XXIII announced the Second Vatican Council, an international conclave of bishops and cardinals to review Catholic teaching. The American Catholic hierarchy mobilized to change the Church’s position on religious freedom. With Murray as their intellectual guide, the American bishops pushed to get American notions of church-and-state separation adopted by the rest of the church. The council debated the topic over several years. A key outside endorsement came from Archbishop Karol Wojtyla of Krakow, Poland, who would later become Pope John Paul II. Cardinal Josef Beran of Czechoslovakia, who had been imprisoned by the Nazis in the Dachau and Theresienstadt concentration camps and then by the Communists a decade later, movingly told his fellow cardinals that “the principle of religious freedom and freedom of conscience must be set forth clearly and without any restriction flowing from opportunistic considerations.”

In the end, the conclave voted 1,997-224 to issue new guidance on religious freedom. The resulting document, Dignitatis Humanae, stated, “This Vatican Council declares that the human person has a right to religious freedom.” Remarkably, according to the Roman Catholic Church, the primary role of government now was promoting not religion but religious liberty: “government is to assume the safeguard of the religious freedom of all its citizens, in an effective manner.” The Vatican position was now fully aligned with the United States Constitution.

Indeed, Dignitatis Humanae was used later by reformers within the Catholic Church who were fighting Communism and other tyrannies. Pope John Paul II’s biographer, George Weigel, argues that he owed his effectiveness, as both archbishop of Krakow and pope, to this Madisonian document. “Absent Dignitatis Humanae,” he wrote, “Pope John Paul II would have been lacking one of the most powerful weapons in his moral armamentarium: the standing of the Catholic Church, post-Dignitatis Humanae, as defender of the religious freedom of all.”

During the 1960 presidential campaign, a group of Protestant ministers in Georgia put their names to an advertisement declaring that they could not vote for John F. Kennedy because he was Catholic. One of the signatories was Dr. Martin Luther King Sr. “Daddy King,” the father of the civil rights leader, was like a lot of traditional Protestants, white and black. He viewed Catholics with suspicion or hostility.

Daddy King changed his attitude in October 1960 after his son was imprisoned for eating at a segregated lunch counter in Atlanta. Martin Jr.’s wife, Coretta, was terrified that he would be killed in jail. While John F. Kennedy, the Democratic Party candidate, had been cautious on civil rights, his advisor, Harris Wofford, convinced him that a simple phone call would make a huge difference.

Kennedy made the call and told Coretta that he was thinking of them and wished them well. Daddy King was impressed. On the night his son was released from jail, he explained, with jarring candor:

“I had expected to vote against Senator

The Kennedy campaign quietly distributed a pamphlet known as “the Blue Bomb,” because of the color of its paper, in African American communities to publicize the call. Kennedy won 68 percent of the black vote, a seven-point improvement over the previous Democratic nominee.

Shortly before Election Day, Wofford was alone with Kennedy. The future president said, “Did you see what Martin’s father said? He was going to vote against me because I was a Catholic, but since I called his daughter-in-law, he will vote for me. That was a hell of a bigoted statement, wasn’t it? Imagine Martin Luther King having a bigot for a father!”

Riots in the 1830, 40s, and 50s

Anti-Catholic bigotry persisted for most of American history. When the Declaration of Independence was signed, nine of the thirteen colonies barred both Catholics and Jews from office. In the 1830s, Protestant mobs burned convents, sacked churches, and collected the teeth of deceased nuns as souvenirs during anti-Catholic riots in the 1830s—just one of the many spasms of “anti-papism” that roiled America.

Less than 1 percent of Americans were Catholic at the turn of the nineteenth century, so the Catholic threat had been largely symbolic. But as a result of immigration from Ireland, the Catholic population surged from 663,000 in 1841 to 3.1 million in 1860, from 4.6 percent of the population to 11.5 percent. Foreign-born people made up more than 45 percent of the populations of New York, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Buffalo, and Detroit.

While early Catholic immigrants tended to be skilled workers, later arrivals were mostly poor and uneducated, many driven from Ireland by the potato famine between 1845 and 1852. Preachers, politicians, and editors sounded a clarion: America was in grave danger.

One prominent New Yorker got a great deal of attention for his nationalist tirades. A celebrity who used his fame in the commercial sector to launch a political career, he argued that a foreign country was intentionally sending us “their criminals” because America did not have sufficient “walls” and “gates” to keep them out. The man was Samuel Morse, the inventor of the telegraph and the Morse code. The religion he assailed, of course, was not Islam, but “Popery.”

The nation he warned about was not Mexico, or even Ireland, but rather Austria, because he believed that an organization based there had hatched a plan to finance the immigration of hundreds of thousands of Catholics. And while Morse did not win his election (for mayorsh of New York City), he had a significant influence on the popular culture through the two books he published in 1835, Foreign Conspiracy Against the Liberties

The Catholic immigrants were decrepit—“halt, and blind, and naked”—and easy to manipulate, Morse wrote. With their “darkened intellects,” they “obey their priests as demigods.” The Europeans could deploy these “senseless machines” to seize power in America, Morse and other anti-Catholic activists said, through our electoral system. The Vatican controlled the priests, who then controlled the voters.

Morse pointed to local elections, in which Catholics were already having an impact. A Jesuit priest had been elected to Congress from Michigan, where the Catholics used colored ballots to help enforce voting discipline. “The cloven foot has already shown itself,” Morse said, via this “truly Jesuitical mode of espionage.” “Up! Up! I beseech you. . . . Shut your gates,” Morse urged.

Anti-Catholics like Morse also viewed Catholicism as a tool of foreign powers. Reverend Lyman Beecher explained the intentions of the European tyrants. By “emptying upon our shores” so many paupers—“the sweepings of the streets”—they would impose heavy burdens on our government and society. The result would be “multiplying tumults and violence, filling our prisons, and crowding our poor-houses, and quadrupling our taxation.” The American Patriot organization called for “sending back Foreign Paupers and Criminals.”

While the Protestant attacks reeked of bigotry, the Catholic Church gave them plenty of ammunition. The Church at various moments of world history had opposed freedom and democracy in Europe and other parts of the world. But what anti-Catholic activists left out was any evidence that American Catholics had rejected the democratic system. After all, the primary means through which Catholics had attempted to reshape America was by setting up schools and charities. And the way they were hoping to gain power was through elections.

When Pennsylvania created its public school system in 1834, the legislature required that it use the Bible to teach morality. By “Bible,” it meant the King James Version. The problem was that, for several hundred years, Catholics had rejected the King James Version in favor of the Douay-Rheims Version. The Catholic Bible included numerous annotations, in keeping with the Catholic tradition that the Bible is best understood with help from priestly experts.

It also kept eight books of what Protestants called Apocrypha that the King James Version had purged, including the books of Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, 1 and 2 Maccabees, and parts of Esther and Daniel. Catholics also used a different version of the Ten Commandments. For Protestants, the third Commandment was “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above.” Catholics had a long tradition of creating literal depictions of Jesus on the cross and icons of the saints.

Philadelphia’s Catholic bishop, Francis Kenrick, objected to Catholic children being forced to read the King James Bible. Born in Dublin, he had immigrated in 1821 after receiving his doctorate, and he now managed a fast-growing diocese. “THE READING OF THE

The members of Philadelphia’s Board of Controllers, which managed the school system, were mostly Protestants, but they knew that the Catholic population had risen from 21 percent in 1808 to 39 percent in 1832. So, they crafted what they thought was a Solomonic compromise. Catholic students should not be forced to read a Bible to which they were “conscientiously opposed.” But while they could bring in a Bible of their own, it had to be one “without note or comment,” which ruled out the Catholic Bible.

Their Liberty of Conscience resolution, as they called it, angered everyone. Protestant leaders thought the board had capitulated to evil, falsely asserting that the Catholics wanted to exclude the Bible from the schools. The Catholics were perfectly free to leave the common schools if they didn’t like them, they argued. “Protestants founded these schools, and they have always been in a majority,” explained an article in the Presbyterian. “Why, then, should the minority who have come in afterwards for the benefits of these schools” get to change the rules?

The Protestant Banner warned that acceding to the Catholic position would mean, in effect, “erecting the cross of the antichrist over our common school houses.”

Philadelphia’s Protestants organized, with more than eighty ministers of various Protestant denominations setting aside their own differences in 1842, to form the American Protestant Association. They maintained that “Romanism . . . under a foreign priesthood” was aggressively trying “to destroy the religious character and influence of public Protestant education.” The American Republican Association, a nativist group, urged that naturalized citizens—those not born in the United States—be excluded from public office.

The next year, a teacher in the Kensington district falsely claimed that her principal had told her to stop teaching from the Bible. A school official then told an audience at a Methodist church that the principal, who was Catholic, was acting under “Popish dictations” and that it was time to “resist such attempts ‘to kick the Bible from the Public Schools.’”

On March 4, 1844, a crowd of more than six thousand gathered across from Independence Hall to “save the Bible.” In response to the agitation, Kenrick hardened his line. While before, he’d asked that Catholic students be excused from reading from the King James Version, he now asked that they be allowed to recite from the Douay-Rheims Version. And if that wasn’t possible, the schools should just avoid Bible readings altogether.

Tensions reached a dangerous level. On May 3, a Protestant group tried to hold a protest meeting in the Catholic area of Kensington, but club-wielding Irish Catholics drove them out. Three days later, more than two thousand Protestants

The nativist press demanded revenge. “We write at this moment with our garments stained and sprinkled with the blood of victims to Native American rights—the rights of conscience,” the Daily Sun declared. Allowing Catholics to read their own Bible amounted to an assault on Protestant freedoms, the Native American declared. It was time “to arm,” since “the bloody hand of the Pope has stretched itself forth to our destruction.”

In the ensuing riot, lasting from May 6 to May 8, about thirty Catholic homes were burned down. Some Protestants took a page from Exodus and adorned the doors of their homes with signs saying “native American” to ensure that the rioters passed them over. The Sisters of Charity convent was destroyed, as was St. Augustine’s Church, including its library of five thousand books. The crowd gave a great cheer when the cross atop St. Augustine’s fell to the ground. Hundreds of Catholic families loaded their possessions into wagons and fled to safety. The governor sent in thousands of soldiers to guard the churches and restore order.

Rise of KKK and Al Smith

Sometime toward the end of the nineteenth century, Roman Catholicism became the largest Christian denomination in America. From 1870 to 1920, nine million Catholics landed in the United States, many from Ireland, Italy, Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Poland, to work in the factories of the Industrial Revolution. The share of the US population that was Catholic rose from 5 percent in the 1850s to 20 percent by 1910, and among the religiously active, the percentage jumped to 32 percent.

In the 1920s, the rise of the second Ku Klux Klan was driven as much by animus toward Catholics as toward blacks and Jews. In 1928, Democrats conducted a laboratory experiment in American tolerance by nominating Alfred E. Smith, who embodied every negative stereotype peddled by fearful Protestants—a Catholic, Tammany Hall–connected, anti-Prohibition Irish-Italian American.

To have one of their own nominated by one of the two major parties was an extraordinary milestone for American Catholics. The four-term governor of New York was a beloved progressive whose policies laid much of the groundwork for the New Deal. But his candidacy brought a level of religious vitriol not seen since the Jefferson-Adams election of 1800.

Throughout the campaign, Smith was depicted as the pope’s puppet. Klansmen claimed that a photo of the recently completed Holland Tunnel in New York City actually showed a newly built secret pathway from Rome to the United States, through which the pope would arrive and take over the country. Around the country, signs appeared making it clear what the main issue was: “For Hoover and America, or For Smith and Rome. Which?”

In Muncie, Indiana, a twofer conspiracy theory spread: the Catholics had invented a powder that would bleach the skins of black men so they could seduce and marry unsuspecting white women. Other fliers claimed that, if Smith

At the Democratic convention in Houston, where Smith became the Democratic nominee, several Klansmen dragged a life-size effigy of him into the convention hall, slit its throat, and threw fake blood on its chest. At one rally, a KKK official told a crowd of five thousand that they stood ready to block Smith from winning the presidency: “There are 6 million people in the United States who have pledged their lives that no son of the Pope of Rome will ever sit in the Presidential chair.”

Nationally, the Klan sharply divided the Democratic Party. At the 1924 Democratic National Convention in New York City, Klan opponents offered an amendment to the party’s platform denouncing the organization. But a staggering 343 delegates were members of the Klan, and many others were sympathizers. The anti-Klan resolution lost by two votes.

KKK march in Queens

In 1927, one thousand white-robed Klansmen joined the regular Memorial Day parade in Queens. The Knights of Columbus, a Catholic group, pulled out of the parade to protest the Klan’s inclusion. Police and Klan members fought, with the police claiming that the Klan had violated a pledge to go hoodless.

Klan members subsequently claimed that “Native-born Protestant Americans” were being “assaulted by Roman Catholic police of New York City.” Their propaganda included the “one school” message that proved so popular in other parts of the country. “Liberty and Democracy have been trampled upon when native-born Protestant Americans dare to organize to protect one flag, the American flag; one school, the public school; and one language, the English language.”

One of the seven people arrested during the rally was Fred Trump, Donald Trump’s father, according to 1927 news accounts. Some newspaper articles said that all of those arrested were Klansmen, but another account said that Trump was detained “on a charge of refusing to disperse from a parade when ordered to do so” and that he was “discharged” at the arraignment.

A separate article in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle described five of the seven—but not including Trump—as Klan members. Donald Trump denied that any of this even happened.

Anti-Catholicism in the mid-twentieth century was not limited to fundamentalists. Many liberals viewed the Catholic Church as a powerfully oppressive force. A bestselling anti-Catholic book in 1949 by the civil libertarian Paul B. Blanshard, American Freedom and Catholic Power, criticized state support of Catholic schools, the Church’s censorship of movies and books, and the ban on birth control in Catholic hospitals. He called for a resistance movement” against the “Catholic plan for America” and its “undemocratic system of alien control.” Some liberals also associated the Church, strongly anti-Communist, with the excesses of McCarthyism and anti-Semitism.

Anti-Catholicism in the 1960s

For most of American history, anti-Catholicism was a central theme of the American experiment. And then, suddenly, at least in terms of the long arc of history, this religious bigotry faded.

How did this sudden change happen?

Between roughly 1960 and 1990, the pace at which Catholics were accepted accelerated. It happened first on the left, as the nomination of a Catholic Democrat, combined with the dynamics of the civil rights and anti-war movements, forged new Protestant-Catholic alliances.

John F. Kennedy’s campaign, just thirty-two years after Al Smith’s drubbing, eroded anti-Catholicism on the left. Like Daddy King, many Democrats who had been suspicious of Catholics found reason to open their minds. Kennedy’s tactical decisions helped. On September 12, 1960, before the Greater Houston Ministerial Association, he laid out a vision that was quintessentially Madisonian but at odds with the traditional approach of the Catholic Church:

“I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute, where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote; where no church or church school is granted any public funds or political preference; and where no man is denied public office merely because his religion differs from the president who might appoint him or the people who might elect him.”

The speech reflected a shift for Kennedy, who earlier in his career had backed government support for Catholic schools. Now, to win on the national instead of the local stage, he opposed such measures as “clearly unconstitutional.” The speech’s message was similar to that of Al Smith, but times had changed. The rise of the tri-faith ethos elevated Catholics as well as Jews. The Catholic vote had become significant, possibly helping Kennedy as much as it hurt him in the 1960 election.

In a sign of just how much Catholic fortunes had changed, when Kennedy became president in 1961, both the majority leader of the House of Representatives, John W. McCormack, and the Senate majority leader, Mike Mansfield, were also Catholic.

Meanwhile, the civil rights and anti-war movements further strengthened relations between liberal Catholics, Protestants, and Jews. Martin Luther King Jr. reached out to religious leaders around the country to join the march in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 and was thrilled to see that more than nine hundred Catholics, including scores of priests and nuns, answered the call.

At the same time that the left embraced Catholicism, an even more dramatic reshuffling occurred among conservatives and religious traditionalists. The rise of the religious right led to more religious pluralism. Conservative Protestants and Catholics united around opposition to abortion, Communism, and secular liberalism, casting aside their traditional theological differences and long-standing cultural animosities.

This period also saw perhaps the greatest example yet of how American values can sometimes alter the complexion of even ancient religions. A dramatic effort by Catholic leaders in the United States, led by an academic named John Courtney Murray, prodded the Vatican to embrace the American approach to religious liberty. This further eased the integration of Catholics

Today, Americans enjoy such robust religious freedom that the litany of anti-Catholic persecutions throughout the country’s history is now horrifying. Proof of how far we have come was on display in 2016 when the United States Supreme Court began its session by seating six Catholics and three Jews as justices. Men and women who would not have been allowed to hold office in early America would pass judgment on the paramount questions of state, including religious liberty.

Finally, it was also on display in 2020, when Joe Biden, a practicing Catholic, won the presidency without his religion being an issue at all.