Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2022, Summer 2025 | Volume 67, Issue 1

Authors: Bruce Watson

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2022, Summer 2025 | Volume 67, Issue 1

Editor's Note: In 2016, Bruce Watson embarked on a journey across the east coast of America to uncover the roots of one of the country's most famous folk ballads, "Shenandoah." His search took him to Virginia, St. Louis, and Oneida, New York, where he interviewed Joan Shenandoah, the late Native American singer-songwriter and seventh-generation descendant of the chief who is thought to have inspired the original song (Shenandoah, who has been described as a matriarch of Indigenous music, passed away in November 2021). An abbreviated version of this article first ran on Watson's history blog, The Attic.

One morning during the brooding October of 2016, I found myself driving along the Miller’s River as it snaked through Western Massachusetts. The sun was a pale disc burning through gauze. The river was draped in mist that softened fall colors. As I sped along Route 2, shaded gorges gave way to ridges, soaring, plunging. I was bound for Boston, yet suddenly I felt westbound, as if I were crossing the Appalachians, headed for a better country, a country I used to know.

Moved by the scenery, I did what you should never do while driving. I took out my phone and began searching for a song. On my left, semis and pickups roared past, sending shudders through my small car. On my right, the river rushed. One slight swerve. . . But I drove on, searching. James Taylor. No. Norah Jones. Sorry…. Blues… Irish…. With hills and hollows as my deejay, I had a single song I had to hear. You know it. Above the din of our lives, you can hear it.

Forget, for a moment, all the would-be anthems written before or since. This land may be my land, but it had come to feel like someone else's. Some still sang "God Bless America," but dirges had lately doused my soul. It had been years since I felt at home anywhere in America, let alone on some range. And as for the dawn’s early light, who among us had seen it lately? But this song…

On that October morning, the song seemed to span centuries. As if bound across the wide Missouri, I drove deeper into a country I knew again. The road took me along the rolling river, then rose above quilts of birch and maple. The song ended, only to be played again with the flick of a thumb.

I had always loved the song; it always brought me to tears. What I love most about “Shenandoah” is that no one knows who wrote it. We don’t know where in America

Seems that Shenandoah was also a Native American chief. But the song I grew up with made scant mention of natives. Written by that greatest of all songwriters, Traditional, Shenandoah's aching beauty proved that tradition knows us well. Tradition knows our longing, knows our dreams, knows how often dreams shift into a sad minor key. And because no one knows who wrote “Shenandoah,” the song owes its power to everyone who ever sang, or will sing it.

The road bound me away, toward Boston. On a busy fall morning, fellow Americans sped past, some listening to the ugly news about the ugly presidential campaign. Others had their own internal music, but none heard a song so lyrical, so lovely, so American as “Shenandoah.”

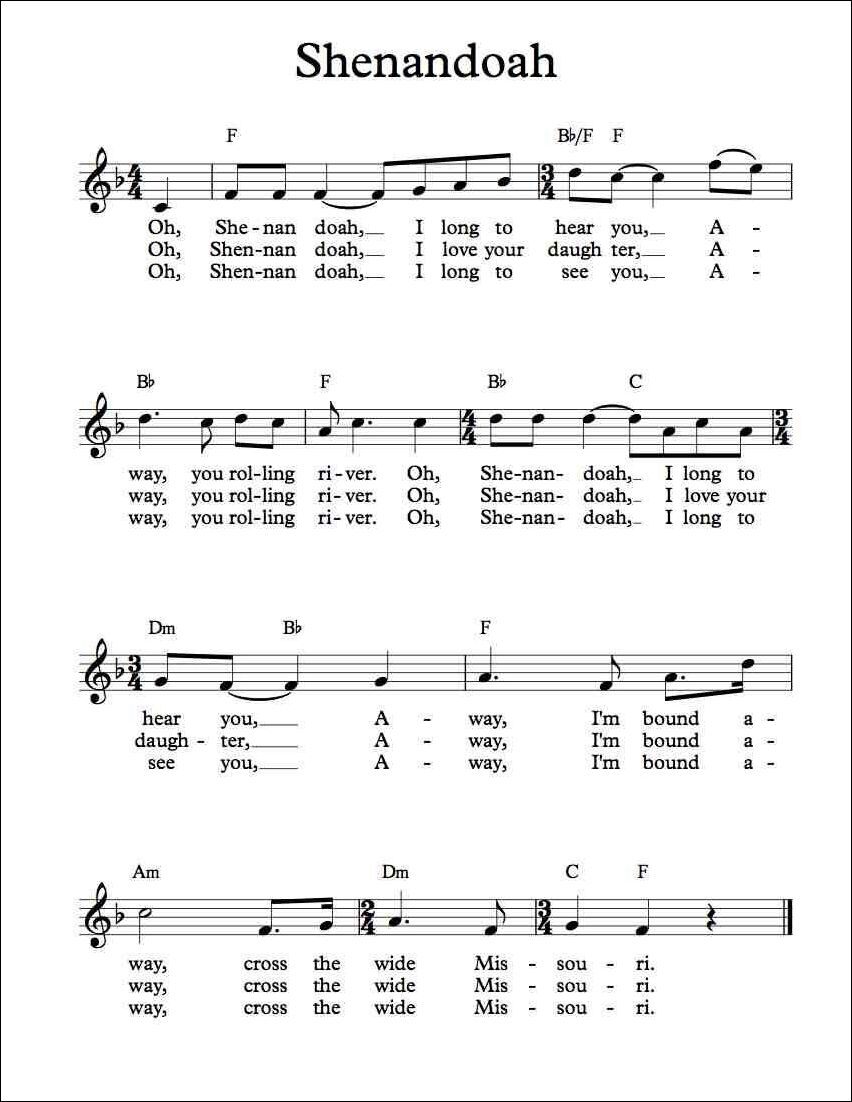

I listened to the song perhaps twenty times, playing and re-playing all the versions on my phone – Bruce Springsteen, Pete Seeger, the haunting violin version from Ken Burns’ “Civil War.” Later, I found a version by Roger McGuinn of "The Byrds.” Recorded in 1973, with a lilting banjo twang, this “Shenandoah” had more ominous lyrics. The singer loved the chief's daughter, all right, but...

These were among the original lyrics, also recorded by Arlo Guthrie. Suddenly "Shenandoah" was not about longing but a story of betrayal, of taking. Because along comes "a Yankee skipper" who...

So "Shenandoah," my new American anthem, was really about getting Native Americans drunk and stealing their daughters. This lilting song, sung by everyone from Tom Waits to the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, started out as a tale of plunder and deceit. Part of me accepted this as the folk tradition, but another part refused. Oh, but it's so lovely. And the lyrics I sang said nothing about drunkenness or stealing daughters. Which "Shenandoah" was I to sing?

Ever since that morning, I have listened again and again to "Shenandoah." I drive now with a “Shenandoah” playlist, listening to McGuinn but also to a jazzy "Shenandoah," Van Morrison's wild version, an Irish fiddle, and more. Which is our song, our "Shenandoah?"

The answer is complex, multi-layered, and just so damned American. The various versions are all our song, just as this is all our country — lovely and triumphant, savage and selfish, with a past we can cherish — until we look a little

* * * * *

As a nation, we share “Shenandoah” and other traditional songs. John Henry. Yankee Doodle. Swing Low, Sweet Chariot. We learn them as kids, then file them away, sharing them only during some drunken sing-along. Until recently, these songs were as passé as "Tom Dooley," Kingston Trio version. Then late in the last century, the old tunes got a new label — "Roots Music." Millennials embraced them, jumpstarting a Roots Revival. A touchstone of the revival was the Coen Brothers' film "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" released in 2000 to mixed reviews. "O Brother" introduced millenials to the music their old folkie grandparents spun on vinyl "back in the day." The soundtrack CD included Mississippi work songs ("Po' Lazarus"), country standards (the Carter Family's "Keep on the Sunny Side"), and the spiritual "O Death," sung by bluegrass pioneer Ralph Stanley, his aged voice like some fine oak sanded against the grain. The soundtrack sold eight million copies, won Grammies, and taught Millenials that America's music transcends rap, hip hop, and the latest by some sneering band of hipsters.

For more than a decade now, young people have been lining up at Roots Music festivals, buying vinyl, dredging up songs and singers not much mentioned since the Sixties. Roots Music has its own channels on Spotify and Pandora. New magazines and folk clubs abound. My fascination with “Shenandoah" seems to stand on solid ground, yet I am not kidding myself. Despite the Roots Revival, America's traditional songs are barely audible above the blather that has become our daily fare. Walt Whitman famously heard “America singing,” but now we only hear America whining, insulting, accusing… It should not take an autumn morning or a minor key to suggest better songs, a better people, and what our best president called “the better angels of our nature.”

"Folk music," said Bob Dylan, "is the only music where it isn't simple. It's never been simple. It's weird, man, full of legend, myth, Bible, and ghosts." Since that fall morning when I risked a head-on collision to hear “Shenandoah,” I have come to see these old songs as stitches to bind a torn nation. Because in these strange times, a shrill, angry tune is stuck in our heads. Like any manic melody played over and over, this song is driving us mad. If it is ever to play itself out, we must listen again to our traditional tunes. Some speak of romance, others of plunder. But they are our songs. You know them. Above the din, you can hear them.

In my twenties, I traveled some 100,000 miles. Hitched. Drove. Rode buses and trains. I crossed America nine times, not flying over but passing through. I came to love my country then, to know it, to accept it. Four decades and one life later, the search for Shenandoah took me back on the road. This time, however, I did not head for Boston. Setting out from my home near the Connecticut River, I went south, I went west, I went off the interstate. I stopped strangers, met music teachers, tourists, counter clerks. I asked each what they knew, what they remembered of "Shenandoah." My search then veered to upstate New York where I found the grave of Chief Shenandoah and spoke with his seventh-generation descendant, singer Joanne Shenandoah.

* * * * *

Scarcely rolling, gently flowing, the Shenandoah River meets the Potomac in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The rivers converge here, forming humpbacked ridges of green and gold that protect this historic setpiece from the insults of time and commerce. On this blustery fall morning, I stand at water's edge near a smoke-black railroad trestle on the banks of the Shenandoah. Before me stretches a silver horizon distant enough to touch the Atlantic. And behind me, this quaint town of cobblestone and covered sidewalks looks as if it were 1859. Any minute now John Brown, crazed and grizzled, will burst out of his hideaway, capture the federal armory on the Potomac and spark the Civil War. But history did not lure me to this landmark. I came for the river.

As a body of water, the Shenandoah River does little to deserve its place in American lore. Compared to the nation's mighty waterways, it is barely a stream. Just 150 miles long, the Shenandoah is too shallow to carry anything but kayaks and canoes. It has no falls to drive factories or mills, no dams to create royal blue reservoirs. Yet even today, humming through our warp-speed culture, the river's name retains its resonance.

Search not on land but on Google and "Shenandoah" comes up as: a national park, a mountain, assorted country bands, a bank, a towing service, a university, a self-storage facility, a liquor store... Most of these are in Virginia, but the lilting name haunts America far beyond the Shenandoah Valley. Shenandoah is a town in Pennsylvania, where the Shenandoah River does not run. And in Iowa, Texas, and New York. The name has graced several navy vessels including a Confederate sailing ship and, in the 1920s, America's first dirigible. California has its own Shenandoah Valley, home to several wineries. Nevada has a Shenandoah Peak, Illinois a Shenandoah State Park. Shenandoah is

"Shenandoah" is always sung with the accent on the first syllable. O SHEN-an-do-ah. The flow makes it hard to imagine the refrain eulogizing any other American river. O Columbia, I long to... O Potomac. . . O Missouri... The song's front-loading explains its power. Stress on the first syllable slides you into the rest, providing the momentum needed when bound away. It's a song that, like all rivers, runs downhill. Skeptics need only sing it wrong — O She-nan-DOAH — to be stopped in their tracks. But sing O SHEN-an-doah, and you're on your way. And I am on mine.

* * * * *

A short climb from the riverbank takes me to Shenandoah Street. (Funny, but when you say the name, you accent the third syllable — Shen-an-DO-ah Street). This stately lane is lined with wrought iron and shuttered houses. Tourists swarm here in July, but today the street is mine. Beneath the looming ridges, along the trickling river, I stroll through time, humming a tune. My first stop is Harpers Ferry National Park headquarters, a two-story brick house. Here I learn much about historic Harpers Ferry. Robert E. Lee slept upstairs in this building, as did Ulysses S. Grant. Meriwether Lewis, before Lewis and Clark set out across the wide Missouri, stocked up on supplies here. For a few minutes, I roam the exhibits, reviewing my high school history. I am about to head out when I spot a graying man at the front desk. Perhaps here, a block from the river, he might know something about the song.

The rest of the year, Jim Madden is a realtor in Fort Collins, Colorado. But each October Madden and his wife volunteer at Harpers Ferry National Park. A daily shift at a desk earns them a room across the street and a chance to live inside this stunning frame of rivers and history. Madden, serene and blue-eyed with a ranger's cap and uniform, looks like a character actor who might play a park ranger. He is reading a paperback mystery with a bright blue cover as I approach. I introduce myself as some fool "searching for Shenandoah." So what about the song? Did he sing it as a boy?

"I sang it growing up in Kansas," Madden tells me. "That's where I got interested in John Brown." (Before coming to Harpers Ferry, Brown began his anti-slavery crusade by hacking up five men in Pottawottomie, Kansas). Before I can ask another question, Madden takes a phone call

— that the Shenandoah Valley was first settled in the 1730s;

— that some lyrics, words he probably did not sing in Kansas, say something about stealing a chief's daughter.

Madden nods but does not share my fascination. Visitors arrive and he begins telling them about the headquarters. Lee slept upstairs. Grant, too. Stonewall Jackson was here. I leave him to his work and step out into a dazzling fall day. The early bluster above the two rivers has cleared, leaving a crisp, clear morning, with just a wisp of clouds. After stopping at a store to buy an Almond Joy, the official candy of the Search for Shenandoah, I head out.

* * * * *

The hardest part about visiting Harpers Ferry is leaving. The leap from 1859 to the present hits you at the first strip mall. No, you say. Take me back in time, back to the age of Lincoln, back to Harpers Ferry. But like flowing waters, time takes you further downriver. Or in this case, upriver. The Shenandoah flows north, forcing folks who live on the south end of the valley to say "we live upriver." They have gotten used to it, but I am not long on the road when I feel lost.

Just outside Harpers Ferry, a sign on eight-lane Highway 340 says "Welcome to the Shenandoah Valley." Split rail fences along the busy highway look like they were built for Ken Burns. I'm in Shenandoah country, all right, but I see no Blue Ridge mountains. And the trickling river in which I stuck my toe for good luck is nowhere to be found. Suddenly my search seems daunting. Plunged into the American Commercial Clutter of fast food and big-box stores, how will I find a tune sung in the days before cars, even before railroads. Back in the early 1800s, when "Shenandoah" is thought to have been written, these United States, always spoken of as plural, had seven million people, including a million slaves. The only Americans living beyond the wide Missouri were natives who knew nothing of this valley or river. Writing these words — yes, too much of what follows was scrawled in ballpoint at 60-plus mph — I miss my turn to Martinsburg, West Virginia. I decide to buy a map.

Heading south, it's a straight shot beneath billowing clouds into Winchester, Virginia, the gateway to the Shenandoah Valley. A Currier and Ives town of ante-bellum storefronts, rustic churches, and brick walkways, Winchester boasts a proud history. Washington slept here, of course. Stonewall Jackson's headquarters is here, a

This glitzy new museum on the edge of Winchester hosts more fine art than history. Featured exhibits present watercolors of the Appalachian sky, but desk clerks are happy to help me. Bob Bensky, a tall, ginger-haired Virginia native, tells me that no museum visitors ever ask about the song "Shenandoah." Ever. He vaguely remembers singing it as a boy. "All I know is that the best version was by the Statler Brothers." And I can hear that version upstairs. I climb the steps to find glass cases holding native-American bowls and hatchets. Echoing through the exhibit is a sweet a capella. "O Shenandoah. . ." Must be the Statler Brothers. I follow the refrain to a video and watch a verse or two. Split-rail fences. Autumn colors. Pure front porch nostalgia. While the brothers, a gospel/country group from these parts, croon "I long to see your smiling valley," I am approached by an elderly lady in a prim black dress. Am I looking for something in particular?

"I'm searching for Shenandoah."

Cummie York volunteers at the museum. She, too, recalls singing "Shenandoah" as a child. She always wondered why it mentioned the 'wide Missouri.' "The Missouri is nowhere near here," she says. "What was that all about?

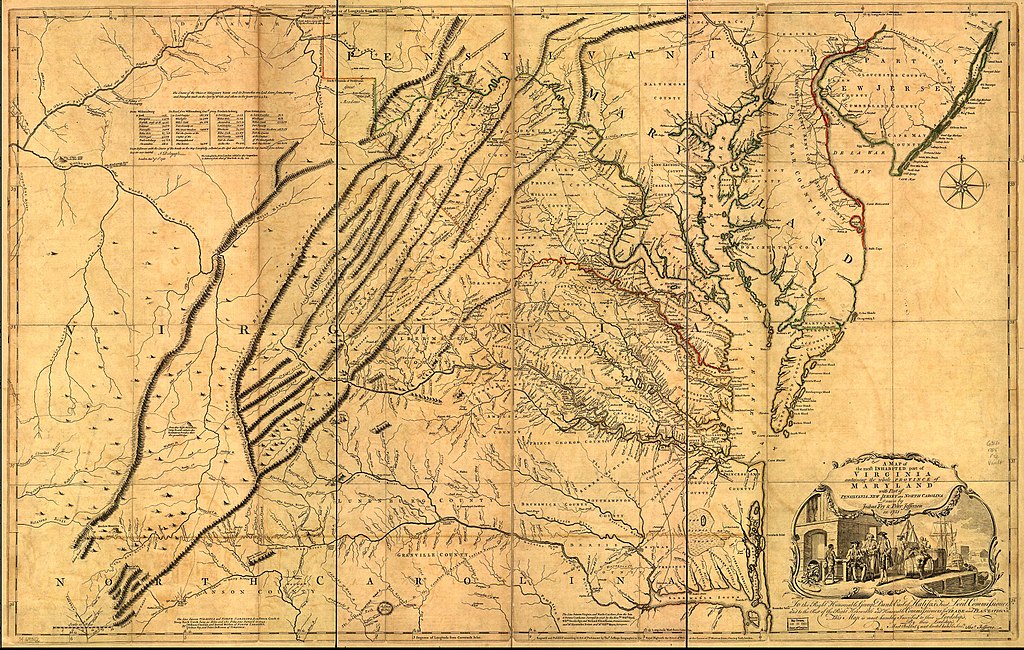

York leads me into the next room where we find a diorama of the Shenandoah Valley. Twenty feet long, lime green with ridges in relief, this is the map I've been wanting. And now I see why I'm confused. The Shenandoah has two forks, each wandering like a rabbit on the run. The North Fork winds out of the Alleghenies, then through the Shenandoah Valley. That's the fork I've followed so far. The South Fork flows on the eastern side of the Blue Ridge. The two forks meet near Front Royal, Virginia, and roll as one to Harpers Ferry. This means John Denver lied, or perhaps flunked geography. "Almost heaven, West Virginia, Blue Ridge Mountains, Shenandoah River..." In fact, the river barely touches West Virginia. Cummie York and I study the diorama but no matter where the river winds, we are nowhere near the wide Missouri. When I ask back at the front desk, someone suggests I contact Warren Hofstra, a professor of history at nearby Shenandoah University.

I rarely drop in on professors. They are perpetually busy, precisely planned, with promises to get back to you at the end of the semester. It would be easier to

In 1730, Virginia's lieutenant governor and a bunch of self-styled "knights" explored the valley, hunting, camping along the South Fork, drinking prodigious quantities of rum, champagne, and hard cider. But Alexander Spotswood and his knights called the river the Euphrates. (O Euphrates, I long to — ). It took another dozen years for a new name to catch on, though no one was sure how to spell it. Variants included Shondore, Chanador, Tschanaator, Jonontore. . .

In Virginia, the name Shenandoah is traced to the Senado Indians who lived here in the 1600s. Virginia legend says Shenandoah means "daughter of the stars." And by the 1780s, when George Washington was recommending the Shenandoah Valley to Revolutionary War vets seeking a place to settle, the name was fixed on maps. Washington Irving, creator of Rip Van Winkle, praised the valley as "equal to the promised land for fertility, superior to it for beauty." But if this valley had drawn just writers and settlers, who would have longed to see its rolling waters? Who would have been bound away?

* * * * *

Back on the Lee Highway, rolling south out of Winchester, I flip on NPR. Suddenly I am afloat in a cesspool of news. I listen to who said what about what the president Tweeted about what someone else said about — I turn off the radio and tap my Shenandoah playlist. The country singer Suzy Bogguss sings one of the sweetest versions I know, just her honeyed voice and a guitar.

Again "Shenandoah" has saved my sinking soul. To my left, the saw-toothed ridges of Shenandoah National Park begin their long march down the valley. To my right, the flatline Alleghenies gild the western horizon. In the valley between, little white churches with little brown steeples dot slopes and meadows. Gone now is the mist I saw as I drove this morning to Harpers Ferry. Whenever this mist hangs above dew-drenched farms, the valley is not "almost heaven" but heaven itself. Early Americans must have walked as if blessed, their pedestrian pace granting them a month of celestial mornings. In their collective memory, the Shenandoah Valley became a paradise lost and longed for.

Driving down US 11, Professor Hofstra informs me, I am tracing America's earliest interstate, the Great Wagon Road. First trod by wood buffalo,

When we think of pioneers, we summon images of the Great Plains, the Oregon Trail, the wide Missouri. But to get there from here, settlers first had to cross the Appalachians. Their route, the same one followed by buffalo and by Iroquois warriors, became the Great Wagon Road. Today, the rolling four-lane of US 11 follows the Wagon Road through tiny towns — Stephens City, Middletown, Strasburg — each sporting an old tavern, a barn I've seen on a calendar somewhere, a dozen perfect porches, and a historical marker detailing what Stonewall Jackson did here. Traffic is light today, as it has been since the 1960s when Interstate 81 diverted the stream of trucks, tourists, and locals pressed for time. So I am left almost alone on what was once the busiest road in the colonies and later, the new country.

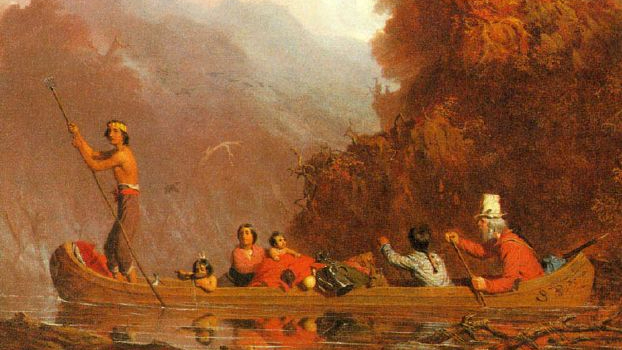

Down this long highway of mud and matted grass came hordes headed west. The Great Wagon Road left Philadelphia, turned south at Lancaster, crossed through Gettysburg, then followed the Appalachians as they slanted across the fresh face of America. Needing a gap in the mountains, migrants saw only ridges so forbidding that even the natives shunned them. The Iroquois had made peace, but migrants found the valley dotted with tepees and longhouses. White families, some bringing slaves, met natives in moccasins and breech cloths, fancied up with shells and feathers. On the road went, past brooding "backcountry" natives called "the dark and bloody land."

Migrants marveled at the valley's untamed beauty. Flocks of pigeons darkened the sky. Panthers and wildcats roamed, preying on deer and wood buffalo before the latter were hunted to extinction. Huddled around campfires each evening, travelers heard the howls of wolves and coyotes. But by day, the river bathed them, gave them water, sparkled in sunlight. Not yet looking back, migrants walked with a jauntiness that impressed one British traveler: "These caravans have a spirit of gaiety

Between the opening of the valley in 1744 and the 1850s, the Great Wagon Road siphoned American restlessness. Historians estimate that this single road carried at least a million migrants along the river and out of this valley. This was, historian David Hackett Fischer noted, "one of the largest migrations in American history." One in four Americans have ancestors who came along this road. That number includes me. Two years after the Civil War, my great-grandfather George Mills, fresh from England, arrived in Staunton, Virginia at the age of ten. Mills eventually settled in Kentucky, where his daughter, my grandmother Lily Mills, was born.

Westward migration filled America's expanding frontier with people homesick for Virginia, the last settled land they had seen. Few states did not have recent arrivals looking back to the Old Dominion. By 1850, Tennessee had almost 50,000 ex-Virginians, Kentucky a few thousand more, and yes, Virginia, there was a wide Missouri, and two-thirds of the state's residents were native Virginians. Among those Midwesterners whose families came from or through Virginia were Abraham Lincoln and Mark Twain, plus some who gave their surnames to cities — James Denver and Jesse Reno, Sam Houston and Stephen Austin. So when a lilting tune arose, its lyrics full of longing for Shenandoah, the song brought tears to so many.

* * * * *

Seven long years. . . But fifty miles upriver and down valley, it occurs to me I have not seen the Shenandoah since Harpers Ferry. The museum diorama showed it following this road, looping more than the Mississippi at its loopiest, carving a sine wave across the landscape. But where?

Woodstock, Virginia calls itself "the Star on the Shenandoah." An inquiry downtown informs me that the river is doing its "Don't Tread on Me" dance just a half-mile to the east. I turn off US 11 and cross South Water Street (getting close) to reach Riverview Park (closer). The park has its own cemetery and manicured Little League fields, but no view of the river. I drive on, winding uphill. Then a half-mile beyond the park, the road turns for a jaw-dropping overlook of a silver river coursing beneath a slope of gold. The Shenandoah earns its reputation here. If I had a canoe I could get lost going back and forth on the river's path through Seven Bends Park.

Having found the river, I wind back to the Great Wagon Road. South of Woodstock, clutter gives way to farmland, making US 11 what it was in the 1700s, a ribbon across a shimmering valley. An orange sun sinks over the Alleghenies. The Blue Ridge skyline slopes past one Civil War battlefield after another. Seems I can almost hear someone singing. But coming into Mount Jackson, my reverie is ended by more chain stores, more fast food. I find another sign of modernity more inspiring. Stopped at a light, I glance over to see a thirty-ish man with brushed blonde hair and athletic attire approach an equally sturdy man with a baseball cap and headphones. One man is white, the other black. Only sixty years ago, the black man would have lowered his eyes or even stepped off the sidewalk as required by the twisted etiquette of Jim Crow. This time, the white man smiles and nods. The black man does the same. The light turns green. I drive on.

Harrisonburg, home to James Madison University, is clogged with students and traffic. Squinting into the sunset, I follow the Great Wagon Road towards Staunton, my great grandfather's port of arrival. The river's North Fork is behind me now, as is my first day of searching. I have seen the Shenandoah flow and traced its valley. But the song? No one I've met could do more than puzzle over its lyrics. Tomorrow I will dig deeper. That night in my Air BnB, I watch "Shenandoah," the movie. Jimmy Stewart plays a feisty old rancher determined to keep his sons out of the Civil War. Then one son is kidnapped by Union soldiers and the rest is Hollywood. I sleep but do not dream of Shenandoah. Enough already.

* * * * *

The next morning, I remember a clue I'd let slip. "People still sing Shenandoah around here," said Dan Harshman, mayor of Edinburg, Virginia. "But they don't walk down the street singing it." The previous afternoon, Harshman had been talking with friends outside the small Shenandoah Valley Cultural Museum in Edinburg. Sorry he couldn't help me, he suggested I "talk to Barbara, one of our council members. She's a musician." And now, seated at Starbuck's, the official coffee of the Search for Shenandoah, I call Barbara Strong. Although she is an hour up valley, she makes it clear that a visit would be worth my time. Because here is

Barbara Strong's home turns out to be a block from where I'd met the mayor of Edinburg the previous afternoon. As Barbara greets me at the door, two yapping Yorkies, Bubbles and Eli, dart around my ankles. Once inside, a glance tells me I'm on the right trail. Perhaps it's the Appalachian dulcimer on one wall. The cello in the next room, maybe? The framed sheet music on walls? The shelf of songbooks beside the zither? Call it a hunch. Barbara, a graying, bespectacled woman resembling every elementary music teacher I can recall, beckons me to sit. She knows "all about Shenandoah."

"If you live in the Shenandoah Valley, people think the song is about the river," she begins. "But the river was named after an Indian chief." She goes to a shelf and returns holding World's Favorite Folk Songs. Page 68 features a sketch of a chief in full-feathered headdress. The lyrics below speak of loving his daughter, nothing more sinister.

Like Jim Madden and Cummie York, Barbara sang "Shenandoah" in school. Asked about her childhood, she points to a photo on the piano, a faded black-and-white with a Big Band ambience. A wide-eyed woman in a long dress sings beside a bow-tied man at a piano. Both seem to glow with song. "My mother and father," Barbara says. Arthur and Dorothy Smith of Roseville, Indiana, a farm town near the center of the Hoosier state. "I had no choice but to be a musician," Barbara says. "I was born into it." Her father, though he sold cars, lived for jazz. Her mother, classically trained, knew all the jazz standards. Barbara studied music at Indiana University and has made a career — fifty years now — performing on cello while teaching piano.

Without my asking, she goes to the grand piano, sets sheet music on a stand and plays "Shenandoah." The notes seem to echo through the valley. I thank her, wishing I could return the favor. I play guitar; Barbara apparently doesn't. But I can play the iPhone! I tap my Shenandoah playlist. Springsteen? A bit gritty for Barbara. The new release I downloaded back at Starbuck's — "Only A River," from the Grateful Dead's Bob Weir? Weir's chorus is based on "Shenandoah," but my trip hasn't been a long, strange one — yet. I choose a mournful fiddle version by Celtic Woman. Before it ends, Barbara and I are blinking back tears. Then with Bubbles and Eli still circling, I ask my signature question. So what is it about this

"Part of the appeal is that no one knows who wrote it," Barbara says. "It might have been a sea captain or a sailor on a boat across the wide Missouri." She hands me The Fireside Book of Folk Songs. On page 34, "Shenandoah" is listed as a capstan shanty. (A capstan is the winch used to hoist heavy sails). So "Shenandoah" was sung more often by boatmen than by farmers missing Virginia. But in today's Virginia, I've noticed, the song is usually sung by choirs, evoking the same provincial pride as Colonial Williamsburg or Monticello. In 2006, during a campaign to make "Shenandoah" Virginia's state song, a choir from Shenandoah University sang it before a legislative committee. The legislature voted down the measure because, as one politician said, "I just don't think we should have a state song about folks leaving the state of Virginia."

Despite its lofty status here, Barbara assures me that "Shenandoah" speaks to all ages. She has heard it as a hymn in church, at festivals here in Edinburg, and from her own cello. I ask to hear it on cello but the instrument is out of tune. I'd wait — all day if it took that — but we move on to her favorite version.

Stonewall Jackson High School auditorium. The town of Mount Jackson, in the shadow of the mountain. The Shenandoah All-County Choir is onstage, 300 students ages 9-18. Rather than sing as one, the choir does "Shenandoah" as Barbara has arranged it in a round. Voices interweave, "rolling around each other. It was just wonderful, so much like the river."

I ask which lyrics the choir sang. "Just the typical ones. 'O Shenandoah, I love your daughter.'" I ask if she has heard lyrics that might not be found in her songbooks. She has. She doesn't know them word for word, but remembers that they spoke of "stealing the chief's daughter." She pauses, the choir version forgotten. "The song is so sadly American in that regard." But she has no answers, no secrets.

A piano lesson is coming up, so I thank Barbara and bid goodbye to the Yorkies. I'll be in touch when I find the full truth about Shenandoah, I say.

My search, having traversed Virginia with only hints of the song's secrets, must find the other fork. I leave Virginia and head home, back to the library. Within a week, I have new search terms: Chief Shenandoah. Oneida Nation. Revolutionary War. Seems that when the Iroquois gave up the Shenandoah Valley, they concentrated their culture away, far away in upstate New York, where a chief named Skenando lived with his seven beautiful daughters.

* * * * *

The colors of Thanksgiving blanket the tabletop landscape of upstate New York. Leaves are fallen, leaving bony tendrils scraping an overcast sky. On a November Sunday morning, I cross the campus of Hamilton College in the town of Clinton. With students sleeping in,

Legends cloud the truth about Chief Shenandoah. Could he have lived to 110? Could he have stood 6'5" in an age when the average man was nearly a foot shorter? Was he a friend of Benjamin Franklin? Was he in Philadelphia at the Continental Congress? Did he visit Virginia's Shenandoah Valley and marvel that it was named for him?

Two legends in this list seem plausible. Biographical dates, including those on the chest-high pedestal here at his grave, list the chief's birth in 1706, his death in 1816. Toward the end of his life, he lamented, "I am an aged hemlock. I am dead at the top. The winds of a hundred winters have whistled through my branches." As to his height, if not a full 6'5", the chief certainly towered over his own people and the colonists who spread his legend. But friendship with Franklin? Present at the creation of America? His visit to the valley? Here the oral tradition remains as murky as the origins of the song bearing his name. And even that name has been smudged by time. On the gray marble pedestal, he is SCHENANDO. Other spellings on this northern fork include: Scanandoa, Skenando, Skenandore, Skennondon... Most history books list him as Skenando or sometimes John Skenandon. But history is firm on the chief's importance to the Oneida.

From the graveside pedestal: "Eloquent and brave, he long swayed the councils of his tribe whose confidence and devotion he eminently enjoyed." Though the chief backed the British in the French and Indian War, by 1775 he was less loyal to the crown. His allegiance to upstart Americans grew from a friendship, one that explains why an Oneida chief is buried at an elite liberal arts college. In 1816, the body of Skenando, as I will call him, was brought here by wagon from his home a dozen miles away. Fulfilling his wishes, the chief is buried beside his friend, founder of the academy that became Hamilton College, named for trustee Alexander Hamilton. Legend has it that the chief, once buried here, hoped to grab the robe of his friend as he was born toward heaven. The friend's grave, beneath a towering obelisk, is just out of arm's reach.

Samuel Kirkland is hardly a household name. Even among those who know the American Revolution, Kirkland is little more than a sidebar. Born in Connecticut, Kirkland came here to Iroquois country, which some called Iroquoia, in 1764 to preach the gospel. "I have from my youth up had a peculiar affection for Indians,"

On the open plain just west of here, Kirkland's sermons drew natives from miles around. The Iroquois believed in twin creators, one benevolent, the other evil, responsible for the world's joy and suffering. Nature was family — Brother Sun, Grandmother Moon, sister spirits of corn, bean, and squash. A savvy missionary, Kirkland accommodated these beliefs yet sweetened the deal with the salvation of Christ. Not all Oneida were swayed but the tall "pine tree chief" Skenando became a lifelong friend of the man who taught him to worship "my Jesus." "Why my Jesus keeps me here so long I cannot conceive," the "aged hemlock" proclaimed. "Pray ye to him, that I may have patience to endure till my time may come.” But first there was a war to survive.

Samuel Kirkland's first decade in Iroquoia was peaceful. Several chiefs and dozens of other Oneida converted to Christianity. But in 1775, disturbing news came from the Eastern seaboard. Rebellion! Shots fired at Lexington and Concord! Revolution! Kirkland decided the Iroquois Confederacy must not get involved. The Continental Congress agreed. "This is a family quarrel," the Congress told an Iroquois delegation to Philadelphia in July 1775. “We desire you to remain at home, and not join either side, but keep the hatchet buried deep.” The British, however, had other plans. Most native nations had supported the crown during the French and Indian War, and British generals counted on that support to help rout the enemy throughout the Mohawk Valley, splitting the colonies in two. Then word came that missionaries born and raised in the colonies might be less loyal.

"Missionaries have it often in their power to lead the minds of the people wrong," British general Thomas Gage wrote to his superintendent of Indian affairs. "Therefore by all means do what you can to get the Indians to drive such Incendiarys from amongst them." To retain native loyalty, British generals made a simple promise. Once the rebellion was crushed, the Iroquois would be left alone. "The Indians well know that in all their landed disputes the Crown has always been their friend," Gage wrote. Along with promises came barrels of rum. Two of the six Iroquois nations, the Mohawks and Senecas, signed on. Each was following another native convert to Christianity, Joseph Brant.

Born with a Mohawk name, Brant was a friend of Samuel Kirkland and even closer to Chief Skenando. Brant had married Margaret, one of the chief's seven beautiful daughters. When she died, Brant married her sister Susanna, who died a year later. Yet Brant had another family tie — his own sister

Throughout the Revolutionary War, New York's Mohawk Valley was a battleground as ruthless as any. Villages were ravaged, crops burned, severed heads spiked on poles. The Mohawk and Seneca, swayed by the charismatic Joseph Brant, fought for the British. The Oneida and others loyal to Samuel Kirkland fought for the new Americans. This Iroquois civil war erupted in the Battle of Oriskany in August 1777, where Mohawk and Seneca slaughtered an Oneida force. Skenando, though not present, had sent a hundred Oneida to fight for the Americans. Despite the carnage, Skenando stuck by the colonists' cause. That winter, he sent four dozen Oneida to Valley Forge to be with Washington's army. There they served as spies and marksmen, once emitting a war-whoop that terrified the British. Legend also has it that Skenando sent corn to Washington's hungry soldiers. Then in 1780, Skenando and three other chiefs went on a peace mission. Early in February, during one of the coldest winters on record, the four chiefs crossed the frozen fields of upstate New York to reach Fort Niagara. There Joseph Brant had turned an old British stronghold into a refugee camp. Roaming its ravaged hordes, Skenando was appalled.

Already worried by his people's weakness for rum, Skenando found Fort Niagara festering with drinking, brawling, and prostitution. Some 3,000 natives clung to life, eating fish heads and maggots. The pine tree chief said nothing about the conditions but he urged other Iroquois to stop supporting the British, to "keep the hatchet well buried." Hearing this, Brant had his father-in-law arrested. The towering chief, then in his mid-seventies, was thrown into a "black hole." Skenando spent five months in Fort Niagara's dungeon, iced over in February, steaming in July. He was only released upon promising to take up a new mission, one that would nearly break him.

Late in the summer of 1780, Joseph Brant and a war party returned to Oneida territory. Skenando was forced to accompany his former son-in-law. Back at Kanonwalohale, Brant ordered the chief to destroy his own village, burn his own house. The village was soon laid waste. The chief's house once stood a few

* * * * *

Morning clouds have melted by the time I drive up Skenandoa Street in the village of Oneida Castle. The village is located on the site of the Oneida settlement the chief put to the torch. The village's small houses, many waving the stars and stripes, are a short drive from a contemporary Oneida landmark, the giant Turning Stone Casino with its Shenandoah Lodge, its denizens feeding slot machines, its native artifacts in gift stores. The casino, built in 1996, split the modern Oneida nation, one side following the money, the other holding to tradition. Tradition's most steadfast champions include the couple waiting for me at the boulder, Mohawk scholar Doug George-Kanentiio and his wife, Joanne Shenandoah.

Seven generations separate Joanne from the chief, but she has traced the family tree. A gifted singer with a Judy Collins voice (I heard her in concert the night before), Joanne has championed Oneida culture in eighteen recordings, many sung in the Oneida language. Along with winning a Grammy, Joanne has sung at the White House and the Vatican, performed with everyone from Patti Smith to The Band's Robbie Robertson, and traveled the world promoting "peace through music." Here, hundreds of miles from the Shenandoah Valley, Joanne and Doug are the perfect confluence of song, history, and tradition. But it's November cold here at the boulder so we agree to talk over breakfast. They suggest Denny's. Just down the road.

We take a table near the register. Before delving into the song, or my hash browns, I ask the couple to separate truth from legend. Yes, Doug tells me. The chief stood 6'5". Did I know that Thomas Jefferson was fascinated by the height of Native Americans? Chief Shenandoah, Doug says, "was the one individual in the colonies that George Washington literally had to look up to." The chief might have met Ben Franklin — once. But Skenandoa did, in fact, attend the Continental Congress in 1775. The chief never visited the Shenandoah Valley.

The Denny's crowd orders Grand Slam breakfasts by the cartload. At our table, dark-haired Joanne, adjusting her black-rimmed glasses, speaks of her music, her heritage, her home located on the original site of Chief Skenando's. (The boulder was moved to make way for Highway 5.) Her husband defers — Oneida culture is matrilineal — until I ask what is known for certain about Skenando. Then this sad-eyed Mohawk, his face gentle

Skenandoa was not born among the Oneida, Doug tells me, but came here as a young man. When his people, the Susquehannock, lost their land in Pennsylvania, he entered Iroquoia through "the south gate." Adopted into the Oneida, the young man flourished. His given name, as if he embodied "O Shenandoah," was Oskanondon. In Oneida, the name refers to deer antlers. (Sorry, Virginia, no "daughter of the stars.") Holding outstretched fingers above his forehead, Doug explains how antlers alert a deer to danger. Yet the chief failed to see the danger of supporting the Americans in the Revolution. Samuel Kirkland had the chief's loyalty, but the wily Joseph Brant proved correct. Once the Revolution was won, the tragic American swan song of native peoples began. Broken treaties. Stolen land. Despair drowned in rum or diaspora. As new Americans swarmed over the Mohawk Valley, some Oneida moved to Canada, others to Wisconsin. Chief Skenando stayed here, struggling to keep his nation intact. Samuel Kirkland, too, lamented the destruction of his beloved Oneida. "The most of my people," Kirkland wrote, "are degenerated as much as our paper currency depreciated in time of war." Chief Skenando spent the rest of his long life immersed in regret. "His spirit was broken," Doug tells me. "He saw he'd made a bad choice, that he had underestimated American avarice and greed, and he felt guilty for hurting his people."

With coffee refilled, Doug and Joanne recount how Skenando was forced to burn his own home and village. Did I know that the village name, Kanonwalohale, means "head on a pole?" They tell me about Sullivan's Raid, the scorched earth campaign George Washington ordered in 1779. Though the Oneida had helped Washington at Valley Forge, the Mohawk and Seneca had to be destroyed. Sullivan's Raid ravaged forty Iroquois villages, torching crops, killing thousands. But "we weren't broken by it," Doug tells me.

"We're still here," Joanne adds. "Still on our land." Have I heard of the Hiawatha Institute, the Iroquois' sparkling new cultural center? Joanne shows me photos on her Macbook.

When history and breakfast have run their course, I ask about the song. Despite scores of versions, Joanne has never released her own. But she considers "Shenandoah" more than a lilting melody about rolling waters. "The song teaches us to long for something lost," Joanne says. "It's about a dream turned into something terrible."

Doug agrees. "It's a tragic song," he says. "It talks about a distant time in America when something was broken." As to specifics, both are sure the song refers to Joanne's ancestor. "There is no other Shenandoah," Doug says. By the end of the revolution, the

And so the skipper was bound away. Here, too, sorrow pervades lyrics and melody. "Whoever wrote the song had the chance to be part of the Skenando family," Doug says, "to blend two cultures He missed that opportunity and realizes it won't come again. That explains the power of the song because we all instinctively feel that loss. It's not about what we have done; it's about what we could have done. 'Shenandoah' addresses that in a way no other American song has."

Wrapping up breakfast, we stand and prepare to part. We exchange recommendations for further reading — Doug is a walking library. Just before we separate, I ask what lessons "Shenandoah," product of a bygone America, might have for the hyper-driven nation we are about to re-enter. Doug pauses. "Americans have lost something," he finally says. "Everyone who studies contemporary America, either culture or politics, sees there have been compromises in the last generation. Americans no longer have a single theme forging themselves into a single people. Americans are adrift now." And "Shenandoah?" "There was a bigger opportunity lost that echoes through the lyrics," Doug says. "About reconciliation. The Americans failed at this point to live with the native people, to learn from them, to share. Instead they suppressed that. Now there's a longing for something less complicated, less divisive. For coming together. All in this tragic song." I bid the couple goodbye. I drive past the Turning Stone Casino, its denizens still feeding the slots. I pass the Iroquois Civil War battlefield at Oriskany, now just fields with historic markers. I cross the Thanksgiving landscape. Home again, I have found the lesson of "Shenandoah."

An aged hemlock. A culture clinging to life. A "pine tree chief" dying, blind and broken. A Yankee skipper, unable to ply the chief with liquor, heads off alone. Looking back, he shares his story, which soon spreads. He or some other singer tweaks the name Skenando, making it resonate with the hordes who came through the heavenly valley, along the snaking river. More verses are added, about rolling waters, seven long years, the wide Missouri. The tendrils of history and folklore flow together into a song that begins its own journey downriver.

Shenandoah, as Barbara Strong's songbook noted, is a capstan

As the song wove through American culture, recorded by Tennessee Ernie Ford, Harry Belafonte, even Bob Dylan, the fate of the Oneida chief and his daughter were forgotten. No more talk of firewater or abduction. But my breakfast with the chief's ancestor shows why we must remember. The words suggest the perils of parsing our cultures into separate tribes. "Shenandoah" is freighted with this lesson — that we must reach out, cross barriers and cultures before it's too late, before all that's left is longing for a life and love left behind. As Doug and Joanne suggested, we all feel this longing, this loss. And that is why we are still singing "Shenandoah."

* * * * *

Scarcely flowing, barely moving, the Missouri River flows into the Mississippi a short drive north of St. Louis. Viewed from the Illinois side, near the fort where Lewis and Clark camped before setting out upriver, the confluence is disappointing. I'm thankful I didn't drive here from either the Shenandoah or Mohawk Valleys. Days of interstates would not have been worth this view of America's most famous rivers trickling together as if overflowing some barren plain. By air and by rental car, I have come again for a river, yet this empty landscape would make anyone long for mist and mountains. Then just as I am about to leave, I spot a skiff at the mouth of the Missouri. Beneath the big sky, a lone figure is paddling against the current. I watch as the skiff slips along the muddy shore. It grows smaller, smaller, as it heads