Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September/October 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 6

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September/October 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 6

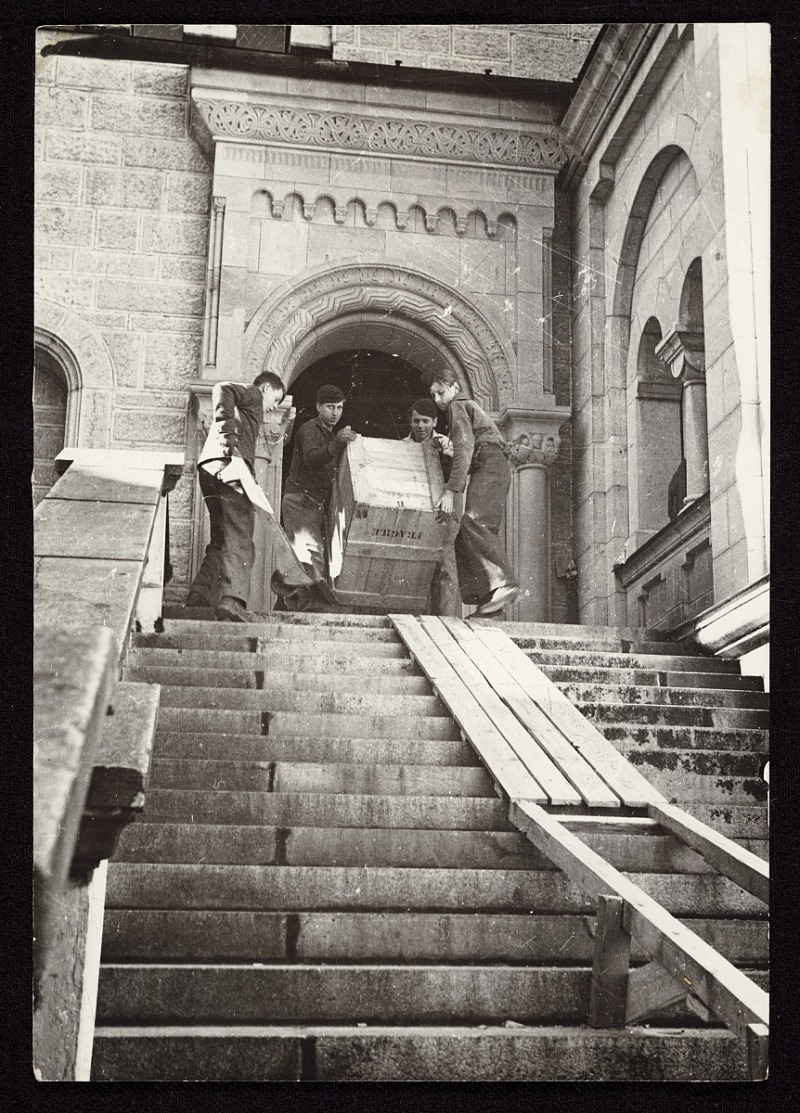

Editor's note: Charles Dellheim teaches history at Boston University. His recent work has focused on the role of Jews in modern culture. In Brandeis University Press’s Belonging and Betrayal: How Jews Made the Art World Modern, excerpted here, Dellheim offers an historical perspective on Nazi art looting by telling the story of a circle of art dealers, collectors, and critics who became pivotal figures in the art world.

On May 3, 1945, a man stood outside the old Carthusian monastery of Buxheim, about 90 kilometers to the north of Munich. The white-walled and red-roofed structure dated back to the 15th century and later had been rebuilt in the Rococo style. The man was squarely built, though not tall. He may have had more heft and less hair than during his student days, but he was more intense, resourceful, and determined than ever. He had not come to the monastery to study its architectural forms or famous decorative carvings, although he would have been at home doing so. Nor had religious impulse driven the man there.

The man was on a mission rather than a pilgrimage. Cleveland-born, Harvard-educated, just shy of forty, Lieutenant James Rorimer was a “Jewish gentleman,” as army intelligence put it and the Curator of Medieval Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, whcre he was in charge of the new Cloisters museum. His first tour of Europe a quarter century before had been entirely different than the present one: before going off to college, he had studied art at the École Gory in Paris and traveled in Germany, the land of his paternal ancestors, although his interior designer father had changed the family name from Rohrheimer in 1917 as anti-German prejudice mounted with America’s belated entry into the First World War.

Rorimer recruited powerful supporters in the art world: among them were Paul Sachs, his Harvard mentor, director of the Fogg Museum and scion of the Goldman Sachs financial dynasty; Robert Lehman, another art-loving heir to a German-Jewish banking family (who later donated a magnificent wing to the Met); and John D. Rockefeller Jr., whose $10 million donation had made the Cloisters possible. Their combined clout pushed the Army into giving him another look. In May 1943, he was allowed to enlist as a private.

Rorimer was tapped soon after—with some help from Sachs, whose reach extended from Cambridge to New York to Washington, DC—for a more suitable task. He joined the newly constituted Monuments, Fine Art, and Archives (MFA & A) section of the US Army as a G-5 (Military Government) Specialist Officer. His comrades were mainly art historians or museum