Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1998 | Volume 49, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April 1998 | Volume 49, Issue 2

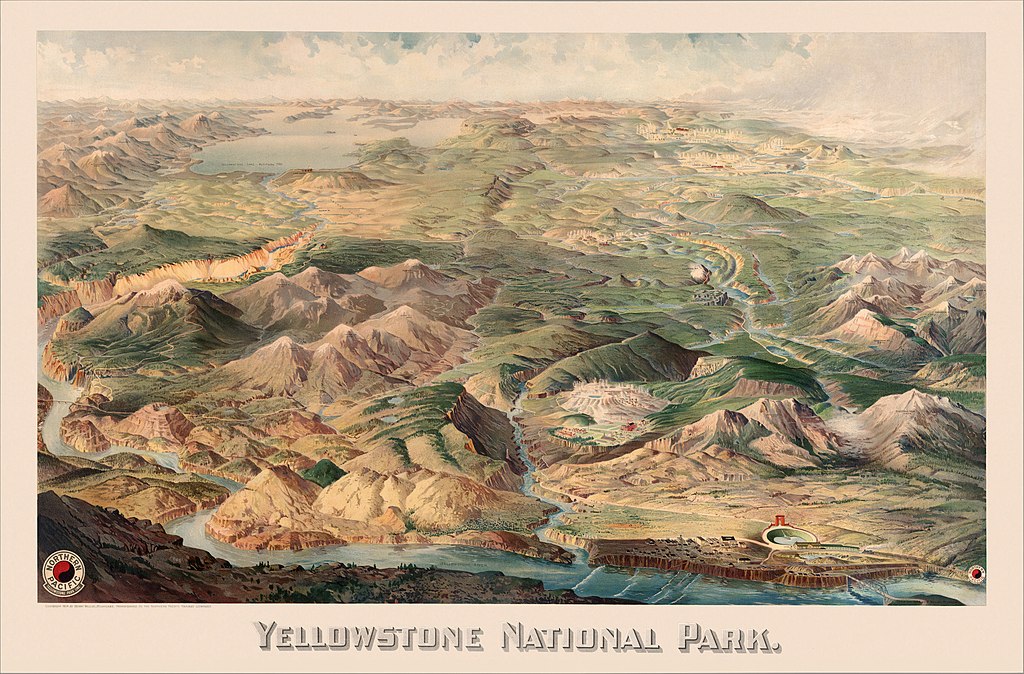

When William Gregg, a manufacturer and national parks enthusiast from Hackensack, New Jersey, visited Yellowstone National Park in 1920, his initial impressions were much like those many visitors take away today. “The tourist automobiles are now so thick on the park road that the superintendent has to establish one-way-street traffic regulations,” he reported in an article for The Saturday Evening Post. “And the designated camping grounds are so inadequate that often the auto caravans find themselves huddled uncomfortably. They fail to get that sense of bigness and freedom for which they come.”

Unlike most of the huddled masses, Gregg had an escape route. His main reason for visiting Yellowstone was to investigate the park’s southwest corner, the little-known, seldom-seen Bechler district. Earlier that year, Idaho’s congressional delegation had introduced legislation designed to help the drought-ravaged sugar beet farmers of its state, igniting the first skirmish in what would become a decade-long battle between conservationists and proponents of irrigation in the region. The legislators proposed placing a reservoir in the park’s Bechler area, reasoning that the land they sought to flood was pretty much useless; even surveyors’ maps had labeled it swamp. The legislation probably would have passed handily if Gregg hadn’t wanted to see for himself the eight thousand acres of meadow Congress seemed set to submerge.

So, Gregg and his two daughters, intent on doing “some real exploration work” through the trackless country to the southwest, accompanied a packhorse outfitter from Old Faithful in August 1920. They crossed the Continental Divide and camped for three nights at the headwaters of the Bechler River, finding three waterfalls, several cascades, a hot spring, and fantastic rock formations—none mentioned on their government-issue topographical maps. From there they proceeded down the eight-mile Bechler River Canyon, past more unnamed waterfalls and cascades, before arriving in the broad basin that had been proposed for the reservoir. “We reached the mouth of the canyon in ample time to make camp for the night, finding solid meadow land, running water, and timber instead of the great swamp shown on the topographical map and so much talked about by the Idaho irrigationists,” Gregg later wrote. “What splendid meadows they are, and surrounded by what fine pine forests! Ten to twenty thousand acres of the best camping country in the world, and every stream is full of native trout!” Gregg added that the “Bechler River Valley is the widest, most level and most beautiful in Yellowstone National Park. Ten thousand individual automobile parties can camp in and around it with elbow room for all.”

Despite Gregg’s prediction, the Bechler Meadows never became a vast campground accommodating ten thousand cars. His writings