Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September/October 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 6

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September/October 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 6

Editor's note: Timothy M. Gay is the Pulitzer-nominated author of two books on WWII. His first article on the U.S. civilian response to the Nazi U-boat threat appeared in American Heritage in 2019.

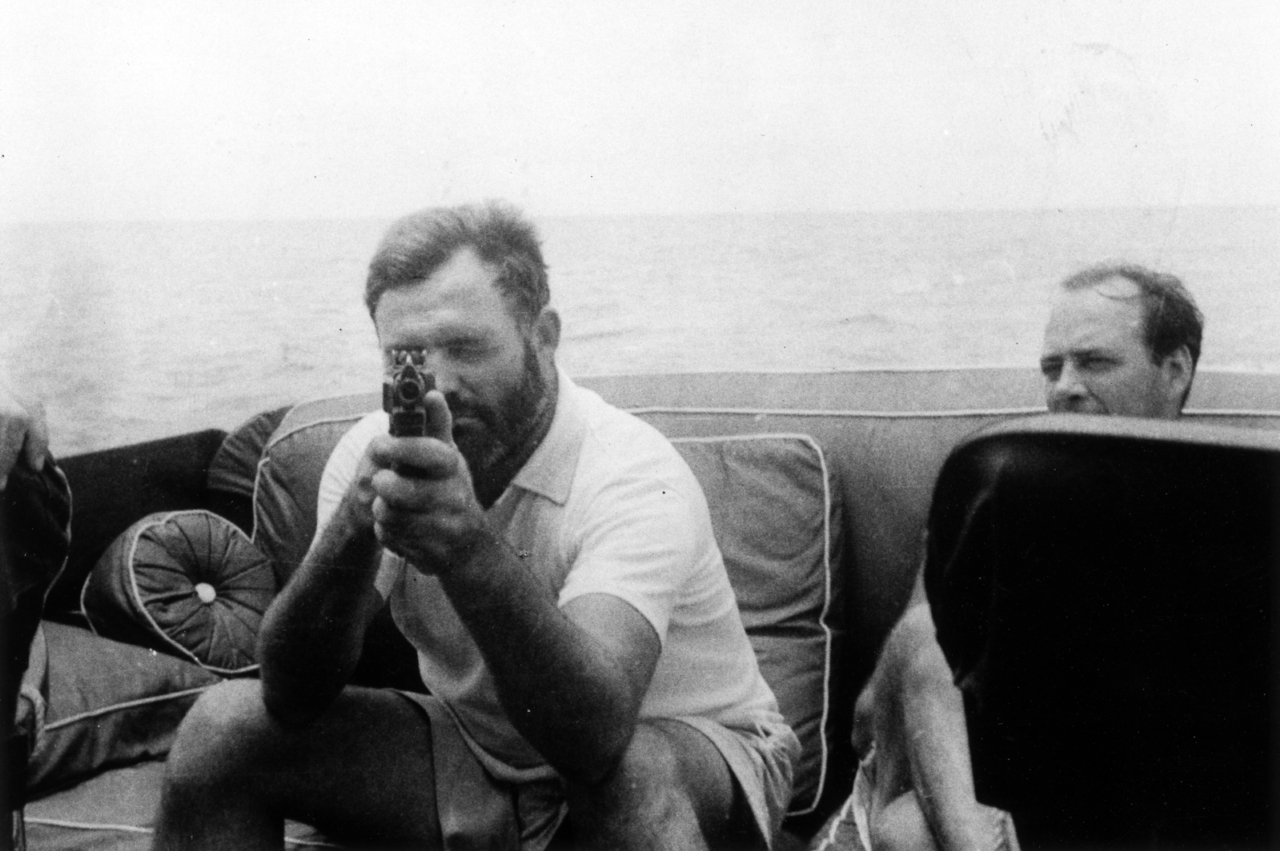

At noon on Wednesday, December 9, 1942, Ernest Hemingway, who loved plumbing the high seas even more than writing about it, was pacing the flying bridge of his 38-foot cabin cruiser Pilar. A pair of powerful binoculars was strapped around his neck. Every few seconds he peered through his field glasses, straining to identify an object roughly six miles out to sea. It was a long gray vessel that, to his novelist’s eyes, was moving suspiciously fast.

He and his crew, among them sons Patrick, 14, and Gregory, 11, had anchored for lunch along the Colorado Reef off the northwest coast of Cuba. Cantankerous crew members had been grousing that the Pilar was no longer stocked with the whiskey that Hemingway had promised. Instead, they had to settle for swigging gin.

From a distance, it appeared that the Pilar, with lengthy poles protruding out of its sides, was no different than the scores of other fishing boats plying the Florida Straits. But upon closer inspection, it was clear the launch was equipped for something other than trolling for swordfish. She was packed to the gills with weaponry: submachine guns, hand grenades, bazookas, and a gnarly looking explosive device that sported handles at both ends. The rectangular bomb looked, Hemingway thought, a little like a coffin.

The U.S. Navy had also outfitted Pilar with special communications gear, including a “Huff-Duff” long-range radio and a sonar detector. She wasn’t pursuing game fish; she was chasing enemy U-boats, with at least the tepid cooperation of the military, from which Hemingway had wangled $30,000 worth of materiel.

He had bought the boat eight years earlier from a shipbuilder in Brooklyn for $7495, a tidy sum in Depression-era America. “Pilar” was the nickname of Hemingway’s second wife Pauline, the mother of Patrick and Gregory, who was still living in Key West despite her 1940 divorce from the boys’wayward father.

It was also the moniker Hemingway hung on the fictitious leader of the Spanish Republican guerilla band in For Whom the Bell Tolls. “Pilar” was a deliberately malicious choice on Papa’s part: Pauline, a devout Catholic, supported Generalissimo Francisco Franco and his fascist-backed Nationalists, incensing Hemingway. The 1941 Pulitzer committee had unanimously recommended For Whom the Bell Tolls be awarded its prize for letters. But the honor was never bequeathed; the president of Columbia University, the academic home of the Pulitzers, found the novel’s themes – and its author – “offensive and lascivious.”

Hemingway’s provocative reputation also stirred