Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1997 | Volume 48, Issue 8

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1997 | Volume 48, Issue 8

Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court spent part of May 6, 1901, writing about the death penalty, and specifically about electrocution. Earlier that day lawyers for Luigi Storti, a 27-year-old Italian laborer without a family in America, convicted for the murder of a fellow immigrant in Boston’s North End, had argued that electrocution was punishment “cruel or unusual,” proscribed by the Massachusetts Declaration of Rights, a charter nine years older than the federal Bill of Rights.

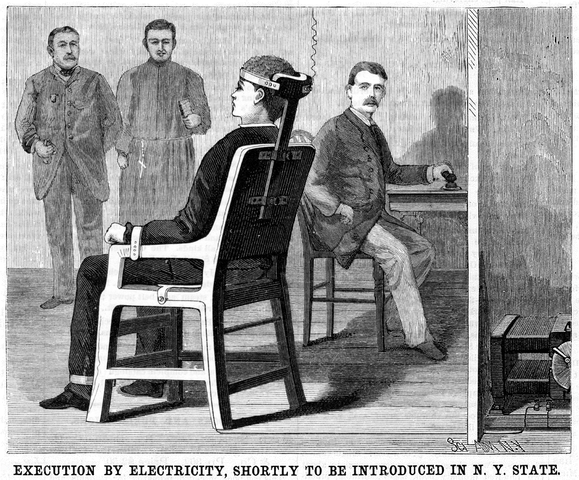

Until 1898, the mode of capital punishment in Massachusetts, as in almost every other state that inflicted death, had been the gallows. The electric chair was supposed to eliminate the uncertainty and pain of hanging (where miscalculation of the “drop” distance might result in slow strangulation or ripping the head from the body), with the aid of the nineteenth century’s secular deity, science, and that newly harnessed miracle, electricity.

Although Storti was to be the first person ever to die in Massachusetts’s electric chair, he naturally cared less about the method of execution than about mere survival. His lawyers’ first move after the guilty verdict had been a straightforward review by the Massachusetts high court focusing on claims of legal error, such as that the statements he had made to the police were not voluntary. That appeal had failed, and so had an effort to obtain an executive commutation and a legislative attempt to abolish the death penalty completely. Then, days before his execution, Storti developed pulmonary hemorrhages, probably from tuberculosis, that left him so weak he would have to be carried to the electric chair. Unwilling to execute a dying man—and hoping for a natural death that would solve everyone’s problems—Governor Murray Crane stayed the execution until May 11.

Then Storti’s health began to improve, and his lawyers presented the petition that Holmes and his colleagues had just considered. With less than a week remaining before execution, Holmes—a fast worker under any circumstances—set out the Court’s views promptly so that, as he put it, “we may avoid delaying the course of the law and raising false hopes in [Storti’s] mind.”

The planned execution, Storti’s lawyers had argued, was cruel or unusual punishment because the procedure involved not only pain and death but also psychological anguish. No, replied Holmes, electrocution was “devised for the purpose of reaching the end proposed as swiftly and painlessly as possible.” Any mental suffering, he added, “is due not to its being more horrible to be struck by lightning than to be hanged with the chance of slowly strangling, but to the general fear of death. The suffering due to that fear the law does not seek to spare. It means that it shall be felt.” Holmes was merely saying in his elegant, direct way that